The Social Brain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

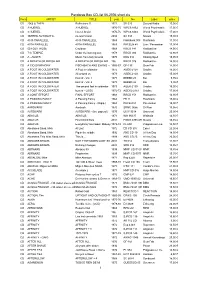

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES: STAHLPLANET – Leviamaag Boxset || CD-R + DVD BOX // 14,90 € DMB001 | Origin: Germany | Time: 71:32 | Release: 2008 Dark and weird One-man-project from Thüringen. Ambient sounds from the world Leviamaag. Black box including: CD-R (74min) in metal-package, DVD incl. two clips, a hand-made booklet on transparent paper, poster, sticker and a button. Limited to 98 units! STURMKIND – W.i.i.L. || CD-R // 9,90 € DMB002 | Origin: Germany | Time: 44:40 | Release: 2009 W.i.i.L. is the shortcut for "Wilkommen im inneren Lichterland". CD-R in fantastic handmade gatefold cover. This version is limited to 98 copies. Re-release of the fifth album appeared in 2003. Originally published in a portfolio in an edition of 42 copies. In contrast to the previous work with BNV this album is calmer and more guitar-heavy. In comparing like with "Die Erinnerung wird lebendig begraben". Almost hypnotic Dark Folk / Neofolk. KNŒD – Mère Ravine Entelecheion || CD // 8,90 € DMB003 | Origin: Germany | Time: 74:00 | Release: 2009 A release of utmost polarity: Sudden extreme changes of sound and volume (and thus, in mood) meet pensive sonic mindscapes. The sounds of strings, reeds and membranes meet the harshness and/or ambience of electronic sounds. Music as harsh as pensive, as narrative as disrupt. If music is a vehicle for creating one's own world, here's a very versatile one! Ambient, Noise, Experimental, Chill Out. CATHAIN – Demo 2003 || CD-R // 3,90 € DMB004 | Origin: Germany | Time: 21:33 | Release: 2008 Since 2001 CATHAIN are visiting medieval markets, live roleplaying events, roleplaying conventions, historic events and private celebrations, spreading their “Enchanting Fantasy-Folk from worlds far away”. -

The Problem with Neurolaw

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 58 Number 2 (Winter 2014) Article 7 2014 The Problem with NeuroLaw David W. Opderbeck Seton Hall University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David W. Opderbeck, The Problem with NeuroLaw, 58 St. Louis U. L.J. (2014). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol58/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW THE PROBLEM WITH NEUROLAW DAVID W. OPDERBECK* ABSTRACT This Article describes and critiques the increasingly popular program of reductive neuroLaw. Law has irrevocably entered the age of neuroscience. Various institutes and conferences are devoted to questions about the relation between neuroscience and legal procedures and doctrines. Most of the new “neuroLaw” scholarship focuses on evidentiary and related issues, and is important and beneficial. But some versions of reductive neuroLaw are frightening. Although they claim to liberate us from false conceptions of ourselves and to open new spaces for more scientific applications of the law, they end up stripping away all notions of “selves” and of “law.” This Article argues that a revitalized sense of transcendence is required to avoid the violent metaphysics of reductive neuroLaw and to maintain the integrity of both “law” and “science.” * Professor of Law, Seton Hall University Law School, and Director, Gibbons Institute of Law, Science & Technology. -

Will There Be a Neurolaw Revolution?

Will There Be a Neurolaw Revolution? ∗ ADAM J. KOLBER The central debate in the field of neurolaw has focused on two claims. Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen argue that we do not have free will and that advances in neuroscience will eventually lead us to stop blaming people for their actions. Stephen Morse, by contrast, argues that we have free will and that the kind of advances Greene and Cohen envision will not and should not affect the law. I argue that neither side has persuasively made the case for or against a revolution in the way the law treats responsibility. There will, however, be a neurolaw revolution of a different sort. It will not necessarily arise from radical changes in our beliefs about criminal responsibility but from a wave of new brain technologies that will change society and the law in many ways, three of which I describe here: First, as new methods of brain imaging improve our ability to measure distress, the law will ease limitations on recoveries for emotional injuries. Second, as neuroimaging gives us better methods of inferring people’s thoughts, we will have more laws to protect thought privacy but less actual thought privacy. Finally, improvements in artificial intelligence will systematically change how law is written and interpreted. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 808 I. A WEAK CASE FOR A RESPONSIBILITY REVOLUTION.......................................... 809 A. THE FREE WILL IMPASSE ......................................................................... 809 B. GREENE AND COHEN’S NORMATIVE CLAIM ............................................. 810 C. GREENE AND COHEN’S PREDICTION ........................................................ 811 D. WHERE THEIR PREDICTION NEEDS STRENGTHENING .............................. 813 II. A WEAK CASE THAT LAW IS INSULATED FROM REVOLUTION .......................... -

Electronic Thesis & Dissertation Collection

Electronic Thesis & Dissertation Collection J. Oliver Buswell Jr. Library 12330 Conway Road Saint Louis, MO 63141 www.covenantseminary.edu/library This document is distributed by Covenant Theological Seminary under agreement with the author, who retains the copyright. Permission to further reproduce or distribute this document is not provided, except as permitted under fair use or other statutory exception. The views presented in this document are solely the author’s. Covenant Theological Seminary Expositing the Scriptures in Preaching to Digitally Saturated Congregants A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Covenant Theological Seminary In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry By Joshua D. Schatzle Graduation Date: May 17, 2019 Abstract Expository preaching in the digitally saturated context of the twenty-first century presents challenges that have been and continue to be under-addressed. A massive media shift, comparable to the dawn of the printing press, has been changing cultures worldwide for over a decade. While resources regarding media ecology are increasingly available—as are resources dealing with expository preaching and culture—preachers lack resources for expositing the scriptures in a digital age, with its shifting epistemologies. The purpose of this study is to examine how preachers navigate the challenges of expositing the scriptures to digitally saturated congregants. Four research questions guided this qualitative study: 1. In what ways do pastors describe the effects of digital saturation on the lives of their congregants? 2. What challenges do pastors experience in intentionally preaching expositionally to engage their digitally saturated congregants? 3. What opportunities do pastors experience in intentionally preaching expositionally to engage their digitally saturated congregants? 4. -

DEAD MASTER's BEAT Catalogue, List Winter 2011/2012

DEAD MASTER'S BEAT Catalogue, List Winter 2011/2012 For more details view: http://deadmastersbeat.de/shop/shop.php or write to: [email protected] o.68 / AMELOTATIST – Todeskult – SPLIT MCD-R || CD-R // 5 € 1917 – Brutal Miserable Drama || CD // 10 € A ACRIMONIOUS – Broken Bonds Of Balance || 7-Inch // 5 € ACRIMONIOUS – Perdition Gospel || TAPE // 5 € ACTA NON VERBA – Lebenskatalyse & Schattenarbeit || TAPE // 7 € ACTA NON VERBA – Logo Black || Button // 1 € ACTA NON VERBA – Logo White || Button // 1 € ALCHEMYST – Blood And Ember || TAPE // 4 € ANACHORET – Am Rande aller Lichter || TAPE // 4 € ANGEL REAPER – Angel Ripping Metal || CD // 10 € ANIMUS MORTIS – Atrabilis (Residues From Verb And Flesh) || CD // 10 € ANNA GARDEK – Bondage Women || CD-R // 13 € ANTIQUUS SCRIPTUM – Ex-Libris || 2CD-R // 4 € ANTRACOT – Neurokinesis || CD-R // 10 € APOLLION – Hungry Of Souls || CD // 10 € ARALLU – Satanic War In Jerusalem || CD // 7 € AREA BOMBARDEMENT – In Hoc Signo Vinces || CD // 13 € ARES KINGDOM – Return To Dust || CD // 10 € ÀRNICA – Numancia || MCD // 9 € ÀRNICA – Viejo Mundo || CD // 13 € ÀRNICA / DÉFILÉ DES ÂMES / SVARROGH – South European Folk Compendium || CD // 13 € ATARAXIA – Lost Atlantis || DIGI-CD // 12 € ATARAXIA – Nosce Te Ipsum || CD // 10 € ATARAXIA – Saphir || DIGI-CD // 12 € ATARAXIA – Simphonia Sine Nomine || DIGI-CD // 12 € ATOMIZER – Logo L || Shirt // 12 € ATOMTRAKT – Sperrstelle Nordost || CD // 13 € AUSTERE – To Lay Like Old Ashes || CD // 10 € AVENGER – Feast Of Anger - Joy Of Despair || CD // 10 € B BANE – Chaos, -

David Eagleman Source URL

How Free Will Probes Mind and Consciousness: David Eagleman Source URL: https://www.closertotruth.com/interviews/2192 Transcript - Long Robert Lawrence Kuhn: David, free will is one of those subjects that can be a probe of what mind is or even the nature of consciousness. It's been very extant in the philosophical literature. Physicists talk about it in terms of determinism and the laws of physics. But neuroscience is where it happens. Neuroscience is, is – explains how we decide things and what it is. So as a neuroscientist, how do you look at free will? How shall we analyze it? David Eagleman: There are a few camps about free will, so not surprisingly there are supporters and detractors of the existence of free will. Here's why a lot of neurobiologists think there is not free will. It's because when you look in the brain, everything is connected to everything else. All the neurons are being driven by other neurons and they're driving other neurons and so what you have is this vastly complex network but in the end, it's a network, it's mechanical. And what you need for a sort of metaphysical free will is an uncaused causer. You need something else in the system that's changing the dynamic properties of this physical stuff even though it's not connected to it directly. Robert Lawrence Kuhn: Because every physical law is caused by a previous physical law. Something happens and there's a chain of events no matter how complicated it is. Everything has a prior physical cause and has a, a forced result which is deterministic. -

Read More Insights Off the Page. Baillie

OFF THE PAGE SOME OF THE INSPIRING AUTHORS WE HEARD FROM IN 2020 – Off The Page CONTRIBUTORS Erica Wagner is an author and critic, and former literary editor of The Times Malcolm Borthwick is managing editor at Baillie Gifford Julia Angeles is an investment manager in the Health Innovation Fund Iain Campbell is a member of the Japanese Specialist Team and a partner in the firm Michael Pye is an investment manager in the Long Term Global Growth Team. EDITOR Colin Renton is an investment writer at Baillie Gifford, having joined the firm in 2007. He is an experienced journalist and a prize-winning short story writer. CM15425 Off the Page WP 0421.indd Ref: 52513 ALL AR 0191 02 RISE OF THE NEW CHINA 04 INVENTIVE MINDS HIDDEN FROM VIEW 06 MAKING SENSE OF NEUROSCIENCE 08 THIS TIME JOBS ARE ON THE LINE 10 LIVE LONG AND PROSPER – Off The Page 2021 OFF THE PAGE Baillie Gifford has supported literary festivals for over 10 years with a goal of helping them to flourish. This reflects the value we place on these events and the work of the fascinating authors who appear at them In 2020, against the backdrop of a to some of these fascinating individuals global pandemic, we maintained our for private sessions. With Covid-19 sponsorship. That enabled many of restrictions in place, the sessions the planned sessions to take place. were conducted online. They gave Some were held face-to-face, but us intriguing author insights and without an audience, others proceeded encouraged us to think in new ways online. -

Neuroscience and Criminal Law: Have We Been Getting It Wrong for Centuries and Where Do We Go from Here?

Fordham Law Review Volume 85 Issue 2 Article 3 2016 Neuroscience and Criminal Law: Have We Been Getting It Wrong for Centuries and Where Do We Go from Here? Elizabeth Bennett British Columbia Court of Appeal Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, and the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth Bennett, Neuroscience and Criminal Law: Have We Been Getting It Wrong for Centuries and Where Do We Go from Here?, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 437 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol85/iss2/3 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEUROSCIENCE AND CRIMINAL LAW: HAVE WE BEEN GETTING IT WRONG FOR CENTURIES AND WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? Elizabeth Bennett* INTRODUCTION Moral responsibility is the foundation of criminal law. Will the rapid developments in neuroscience and brain imaging crack that foundation—or, perhaps, shatter it completely? Although many scholars have opined on the subject, as far as I have discovered, few come from a front-line perspective. The concept of English (now Anglo-American) criminal law has evolved slowly but surely over the past one thousand years. It has responded, in part, to knowledge of the human condition and, -

Front Line Assembly - Bio

FRONT LINE ASSEMBLY - BIO Front Line Assembly is the primary focus of Vancouver-based musician Bill Leeb. A founding member of Skinny Puppy, Leeb moved on to form FLA in 1986 with Michael Balch, releasing some cassettes (since released as Total Terror I & II) which paved the way for their 1987 releases: The Initial Command, State of Mind, and Corrosion. In late 1988, they recorded the mini-LP Disorder, since combined with Corrosion and released as Corroded Disorder. Their 1989 release, Gashed Senses and Crossfire, further cemented their popularity in the industrial scene, and prompted their first world tour. By 1990, Balch had departed and Rhys Fulber rounded out the duo, releasing Caustic Grip. But it was two years later when the duo released the classic album, Tactical Neural Implant, which has become for many, the genre's crowning moment. To this day, TNI still defines the best of industrial music. FLA enraged many of their fans in 1994 when they began to experiment with their established electronic-only sound. Millenium, with its heavy doses of live and sampled metal guitars, dared its audience to grow and expand with the band beyond industrial's perceived barriers. Front Line stepped to the firing line again in 1995 with Hard Wired, which reflected both a return to form and a continued embracing of the guitar. Hard Wired not only picked up where Implant left off, it improved on the sound by adding in elements of all of their side projects. A fall European tour was recorded for the 1996 release Live Wired, their first concert CD ever. -

107 V Ariations on the Unexpected

107 Variations on the Unexpected SURPRISE 107 Variations on the Unexpected Dedication and Prelude To Raine Daston In his essay “Of Travel,” Francis Bacon recommends that diaries be used to register the things “to be seen and observed.” Upon returning home, the traveler should not entirely leave the visited countries, but maintain a correspondence with those she met, and let her experi- ence appear in discourse rather than in “apparel or gesture.” Your itineraries through a vast expanse of the globe of knowledge seem to illustrate Bacon’s recommendations, and have inspired many to em- bark on the exploration of other regions—some adjacent, some dis- tant from the ones you began to clear. Yet not all have journeyed as well equipped as you with notebooks, nor assembled them into a trove apt to become, as Bacon put it, “a good key” to inquiry. As you begin new travels, you may add the present collection to yours, and adopt the individual booklets as amicable companions on the plane or the U-Bahn. Upon wishing you, on behalf of all its contributors, Gute Reise! and Bon voyage!, let us tell you something about its gen- esis and intention. Science depends on the unexpected. Yet surprise and its role in the process of scientific knowledge-making has hitherto received lit- tle attention, let alone systematic investigation. If such a study ex- isted, it would no doubt have been produced in your Department at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. The topic is a seamless match with your interest in examining ideals and practices of scientific and cultural rationality—ideals and practices often so fundamental that they appear to transcend history or are overlooked altogether. -

Jordin Sparks Incubator CONDITIONS FAVORABLE for REACTION

The Anticipated Return of Spotlight THE BES T NEW AND C ATALOG MUSI C AUGUST 10-23 2015 Annual Spotlight on Classical Pgs. 9-16 Salute to Bluegrass & Americana Pgs. 17-20 Get Disturbed Pg. 4 Jordin Sparks incubator CONDITIONS FAVORABLE FOR REACTION SIMMERING JUST UNDER THE SURFACE, THESE TITLETITLESES AARERE ABOUT TTO BREAK FREE. BE AAHEADD OF THE CREATIVE CURVECURVE.. BUTCHER BABIES: FEAR FACTORY: IMBRUGLIA, NATALIE: TAKE IT LIKE A MAN GENEXUS MALE CD: UPC: 727701925325 CD: UPC: 727361344726 CD: UPC: 888750339522 ISBN: 9786316170330 ISBN: 9786316164049 ISBN: 9786316159595 MMSRP: $15.98 Genre: POP/ROCK MMSRP: $15.98 Genre: POP/ROCK MMSRP: $11.98 Genre: POP/ROCK Street Date: 8/21/15 Street Date: 8/7/15 Street Date: 7/31/15 Thhe Butcher Babies return with their highlg y Fear Factory’s ninth studio album is entitled Three-time Grammy® nominee, songwriter, actor and anticipated second full-length, featuring the Genexus. Genexus is the band’s debut on NucN lear model, Natalie Imbruglia, returns with the release of unstoppable co-lead vocalists Carla Harvey and Blast and a powerful return to form for one of the her neww album Male. Imbruglia fi nds inspiration for Heidi Shepherd. The L.A. based band’s deebut originators of “cyber-metal.” 2012’s The Induustrialist, her new album from her favorite male songwwriters. sshot to #3 on the Heatseekers chart and sold oover 9,000 copies in the first week of release Male is a collection of songs all performed by men has scanned 24K units. in the USA and debuted at #38 on the Billboab rd including Cat Stevens (“The Wind”), Tom Petty (“The Top 200.