Lecture I Handout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Worldviews*

RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEWS* SECULAR POLITICAL CHRISTIANITY ISLAM MARXISM HUMANISM CORRECTNESS Nietzsche/Rorty Sources Koran, Hadith Humanist Manifestos Marx/Engels/Lenin/Mao/ The Bible Foucault/Derrida, Frankfurt Sunnah I/II/ III Frankfurt School Subjects School Theism Theism Atheism Atheism Atheism THEOLOGY (Trinitarian) (Unitarian) PHILOSOPHY Correspondence/ Pragmatism/ Pluralism/ Faith/Reason Dialectical Materialism (truth) Faith/Reason Scientism Anti-Rationalism Moral Relativism Moral Absolutes Moral Absolutes Moral Relativism Proletariat Morality (foster victimhood & ETHICS (Individualism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) /Collectivism) Creationism Creationism Naturalism Naturalism Naturalism (Intelligence, Time, Matter, (Intelligence, Time Matter, ORIGIN SCIENCE (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) Energy) Energy) 1 Mind/Body Dualism Monism/self-actualization Socially constructed self Monism/behaviorism Mind/Body Dualism (fallen) PSYCHOLOGY (non fallen) (tabula rasa) Monism (tabula rasa) (tabula rasa) Traditional Family/Church/ Polygamy/Mosque & Nontraditional Family/statist Destroy Family, church and Classless Society/ SOCIOLOGY State State utopia Constitution Anti-patriarchy utopia Critical legal studies Proletariat law Divine/natural law Shari’a Positive law LAW (Positive law) (Positive law) Justice, freedom, order Global Islamic Theocracy Global Statism Atomization and/or Global & POLITICS Sovereign Spheres Ummah Progressivism Anarchy/social democracy Stateless Interventionism & Dirigisme Stewardship -

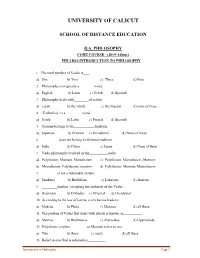

Introduction to Philosophy

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. PHILOSOPHY CORE COURSE - (2019-Admn.) PHL1 B01-INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 1. The total number of Vedas is . a) One b) Two c) Three d) Four 2. Philosophy is originally a word. a) English b) Latin c) Greek d) Spanish 3. Philosophy deals with of reality. a) a part b) the whole c) the illusion d) none of these 4. ‘Esthetikos’ is a word. a) Greek b) Latin c) French d) Spanish 5. Taoism belongs to the tradition. a) Japanese b) Oriental c) Occidental d) None of these 6. does not belong to Oriental tradition. a) India b) China c) Japan d) None of these 7. Vedic philosophy evolved in the order. a) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism c) Polytheism, Monotheism, Monism b) Monotheism, Polytheism, monism d) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism 8. is not a heterodox system. a) Samkhya b) Buddhism c) Lokayata d) Jainism 9. implies ‘accepting the authority of the Vedas’. a) Heterodox b) Orthodox c) Oriental d) Occidental 10. According to the law of karma, every karma leads to . a) Moksha b) Phala c) Dharma d) all these 11. The portion of Vedas that deals with rituals is known as . a) Mantras b) Brahmanas c) Aranyakas d) Upanishads 12. Polytheism implies as Monism refers to one. a) Two b) three c) many d) all these 13. Belief in one God is referred as . Introduction to Philosophy Page 1 a) Henotheism b) Monotheism c) Monism d) Polytheism 14. Samkhya propounded . a) Dualism b) Monism c) Monotheism d) Polytheism 15. is an Oriental system. -

Studia Culturologica Series

volume 22, autumn-winter 2005 studia culturologica series GEORGE GALE OSWALD SCHWEMMER DIETER MERSCH HELGE JORDHEIM JAN RADLER JEAN-MARC T~TAZ DIMITRI GINEV ROLAND BENEDIKTER Maison des Sciences de I'Homme et de la Societe George Gcrle LEIBNIZ, PETER THE GREAT, AND TIIE MOUERNIZAIION OF RUSSIA or Adventures of a Philosopher-King in the East Leibniz was the modern world's lirst Universal C'itizen. Ilespite being based in a backwater northern German principalit). Leibniz' scliolarly and diploniatic missions took liim - sometimes for extendud stays -- everywhere i~nportant:to Paris and Lotidon, to Berlin, to Vien~~nand Konie. And this in a time when travel \vas anything birt easy. Leibniz' intelluctual scope was ecli~ally\vide: his philosophic focus extended all the way ti-om Locke's England to Confi~cius'C'hina, even while his geopolitical interests encom- passed all tlie vast territory from Cairo to Moscow. In short, Leibniz' acti- vities, interests and attention were not in the least hounded by tlie narrow compass of his home base. Our interests, however, must be bounded: to this end, our concern in what follows will Iiniil itself to Leibniz' relations with tlie East, tlie lands beyond the Elbe, the Slavic lands. Not only are these relations topics of intrinsic interest, they have not received anywhere near tlie attention they deserve. Our focus will be the activities of Leibniz himself, the works of the living philosopher, diplomat, and statesman, as he carried them out in his own time. Althoi~ghLeibniz' heritage continues unto today in the form of a pl~ilosophicaltradition, exa~ninationoftliis aspect of Leibnizian influ- ence nli~stawait another day. -

Intro to Perception

Intro to Perception Dr. Jonathan Pillow Sensation & Perception (PSY 345 / NEU 325) Spring 2015, Princeton University 1 What is Perception? stuff in the world 2 What is Perception? stuff in the world percepts process for: • extracting information via the senses • forming internal representations of the world 3 Outline: 1. Philosophy: • What philosophical perspectives inform our understanding and study of perception? 2. General Examples • why is naive realism wrong? • what makes perception worth studying? 3. Principles & Approaches • modern tools for studying perception 4 Epistemology = theory of knowledge • Q: where does knowledge come from? Answer #1: Psychological Nativism • the mind produces ideas that are not derived from external sources 5 Epistemology = theory of knowledge • Q: where does knowledge come from? Answer #1: Psychological Nativism • the mind produces ideas that are not derived from external sources Answer #2: Empiricism • All knowledge comes from the senses Proponents: Hobbes, Locke, Hume • newborn is a “blank slate” (“tabula rasa”) 6 Epistemology = theory of knowledge • Q: where does knowledge come from? Answer #1: Psychological Nativism vs. Answer #2: Empiricism • resembles “nature” vs. “nurture” debate • extreme positions at both ends are a bit absurd (See Steve Pinker’s “The Blank Slate” for a nice critique of the blank slate thesis) 7 Metaphysics 8 Metaphysics = theory of reality • Q: what kind of stuff is there in the world? Answer #1: Dualism • there are two kinds of stuff • usually: “mind” and “matter” Answer #2: Monism • there is only one kind of stuff “materialism” “idealism” (physical stuff) (mental stuff) 9 Philosophy of Mind Q: what is the relationship between “things in the world” and “representations in our heads”? 10 1. -

Psyc104 Summaries

PSYC104 SUMMARIES HISTORY IN PSYCHOLOGY Understanding philosophical foundations of scientific method in psych is necessary to constructively critique and evaluate theories GREEK ORIGINS OF WESTERN THOUGHT Pythagoras Numbers explain universe Perfection found in mathematical world Mind/ body dualism: sense/flesh inferior Plato Combined Socratic method (digging deep into ideas) w Pythagorean mysticism Theory of forms: physical objects = inferior representation of pure ideas True knowledge gained by grasping ideas, ignoring sensory experience Mathematics does not explain everything Aristotle First major psychologist: examined memory, sensation etc. Studied nature Rationalist empiricist: analyze info from senses to produce knowledge Explain psych events in terms of biology: physiological psychologist Significance of Axial/pivotal period à question ideas Ancient Greeks for Open discussion and debate valued and encouraged Western Psych Establishment of rigor/ critical/ analytical thinking THE DARK AGES IN THE WEST Dark Ages in the Greek learning largely lost in West: halts open inquiry re nature of West human beings Adherence to faith (Church)/ mysticism/ anti- intellectualism > role of human reason Preservation of Greek learning by Islamic scholarship Dark à Middle … rediscovery of Aristotle’s work à reawakening of inquiry Ages Establishment of universities: debate and engagement w world Rise of Humanism RENAISSANCE HUMANISM Renaissance Social/intellectual focus on human beings Humanism 4 prominent themes: (I) individualism, (II) personal religion, -

Epistemology

EPISTEMOLOGY The subject term ‘Epistemology’ comes from two Greek words: episteme meaning “knowledge” and logos meaning “study – account – theory.” Thus, ‘Epistemology’ is “the philosophical study of knowledge” and a chief concern of Epistemology has been the development of an adequate “theory of knowledge.” Epistemology asks the questions: “What is ‘knowledge’? – What do you possess when you possess’ knowledge’? – What are you claiming when you claim to possess ‘knowledge’?” (see “the Standard Analysis of Knowledge”) “HOW do we know?” “WHAT do we know?” – What kinds of thing are we able to know? What do we not know – What kinds of things might we not be able to know? – “What are the LIMITS of knowledge?” The issue is not: “DO we know anything at all?” Radical Skepticism (‘global skepticism’) would undermine itself and one cannot even get started claiming / asserting that we cannot know anything. (See “A Refutation of Radical Skepticism” also on this webpage) However, ‘Local Skepticism’ – doubt about the ability of particular methods or areas of inquiry to provide knowledge, and doubt about particular claims as being instances of knowledge, is very much possible and appropriate to the critical enquirer. There are two Major Traditions in epistemology in the western intellectual tradition: Rationalism and Empiricism 1. “Inside-Out” knowing 1. “Outside-In” knowing 2. affirms ‘innate ideas’ 2. rejects ‘innate ideas’ 3. rejects mind as a tabula rasa 3. affirms mind as a tabula rasa 4. affirms apriori knowledge 4. rejects apriori knowledge – all knowledge is aposteriori 5. Mathematical model / Deductive logic 5. Induction model / Inductive logic 6. Certainty the standard for knowledge 6. -

Human Mind Is a Tabula Rasa

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Human Mind is a Tabula Rasa Subhani, Muhammad Imtiaz and Osman, Ms. Amber Iqra University Research Centre (IURC), Iqra university Main Campus Karachi, Pakistan, Iqra University 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/34733/ MPRA Paper No. 34733, posted 15 Nov 2011 16:14 UTC Published in INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH IN BUSINESS Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 1173 - 1176, July (2011) HUMAN MIND IS A TABULA RASA* *The Latin term Tabula Rasa equates to the English "blank slate" MUHAMMAD IMTIAZ SUBHANI, HEAD RESEARCH – IURC IQRA UNIVERSITY RESEARCH CENTRE- IURC IQRA UNIVERSITY – IU, MAIN CAMPUS, POSTAL ADDRESS: DEFENCE VIEW, SHAHEED-E-MILLAT ROAD (EXT.) KARACHI- AMBER OSMAN ASSISTANT MANAGER RESEARCH – IURC IQRA UNIVERSITY RESEARCH CENTRE- IURC IQRA UNIVERSITY – IU, MAIN CAMPUS, Postal address: Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi- Abstract The Latin term Tabula Rasa equates to the English "blank slate" (which refers to writing on a slate sheet with chalk). Tabula rasa is the epistemological study that a human is born with no built-in mental content and that human knowledge comes from experience and perception. Generally exponents of the tabula rasa study favors the "nurture" side of the nature, when it comes to aspects of one's personality, social, emotional behavior, and intelligence. Keywords: Tabula Rasa, Blank Slate, John Locke, Nurture, Knowledge. 1. Introduction Tabula Rasa has been referred in different contexts depending upon the mode of work. Different concepts arose from this term to a wider perspective and research studies by different people. Mostly in the 20th century, the swings to this study was attached to character withdrew racism and then follows the gender identity as a communal structure, which is at present most commonly in use. -

Empiricist Roots of Modern Psychology

Raymond Martin Department of Philosophy Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 USA Empiricist Roots of Modern Psychology From the thirteenth through the sixteenth centuries, European philosophers were preoccupied with using their newfound access to Aristotle’s metaphysics and natural philosophy to develop an integrated account, hospitable to Christianity, of everything that was thought to exist, including God, pure finite spirits (angels), the immaterial souls of humans, the natural world of organic objects (plants, animals, and human bodies) and inorganic objects. This account included a theory of human mentality. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, first in astronomy and then, later, in physics, the tightly knit fabric of this comprehensive medieval world view began to unravel. The transition from the old to the new was gradual, but by 1687, with the publication by Isaac Newton (1642-1727) of his Principia Mathematica, the replacement was all but complete. Modern physical science had fully arrived, and it was secular. God and angels were still acknowledged. But they had been marginalized. Yet, there was a glaring omission. Theorists had yet to expand the reach of the new science to incorporate human mentality. This venture, which initially was called “moral philosophy” and came to be called “the science of human nature,” became compelling to progressive eighteenth century thinkers, just as British empiricism began to seriously challenge an entrenched Cartesian rationalism. Rationalism and Empiricism The dispute between rationalists and empiricists was primarily over concepts and knowledge. In response to such questions as, where does the mind get its stock of concepts, how do humans justify what they take to be their knowledge, and how far does human knowledge extend, rationalists maintained that some concepts are innate, and hence not derived from experience, and that reason, or intuition, by itself, independently of experience, is an important source of knowledge, including of existing [25] 1 things. -

Rene Descartes and the Legacy of Mind/Body Dualism

Rene Descartes and the Legacy of Mind/Body Dualism MIND AND BODY: by Robert René Descartes to William H. James Wozniak RENÉ DESCARTES AND THE LEGACY OF MIND/BODY DUALISM 1. René Descartes 2. The 17th Century: Reaction to the Dualism of Mind and Body 3. The 18th Century: Mind, Matter, and Monism 4. The 19th Century: Mind and Brain 5. Mind, Brain, and Adaptation: the Localization of Cerebral Function 6. Trance and Trauma: Functional Nervous Disorders and the Subconscious Mind René Descartes 1. René Descartes http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/Mind/Descartes.html (1 von 4) [08.08.2002 19:08:48] Rene Descartes and the Legacy of Mind/Body Dualism While the great philosophical distinction between mind and body in western thought can be traced to the Greeks, it is to the seminal work of René Descartes (1596-1650) [see figure 1], French mathematician, philosopher, and physiologist, that we owe the first systematic account of the mind/body relationship. Descartes was born in Touraine, in the small town of La Haye and educated from the age of eight at the Jesuit college of La Flèche. At La Flèche, Descartes formed the habit of spending the morning in bed, engaged in systematic meditation. During his meditations, he was struck by the sharp contrast between the certainty of mathematics and the controversial nature of philosophy, and came to believe that the sciences could be made to yield results as certain as those of mathematics. From 1612, when he left La Flèche, until 1628, when he settled in Holland, Descartes spent much of his time in travel, contemplation, and correspondence. -

PHILOSOPHY A-LEVEL 2019-2020 “What Syllabus Would I Be Following?” We Study the 7172 AQA a Level Philosophy Specification

NORTHGATEIPSWICH SIXTH FORM CENTRE Gilbert Hilary Putnam Ryle Knowledgecategory errorqualia Hempel Ned Folk Psychology Plato Eliminative Materialism inverted qualia Churchland FunctionalismBlock Anita Avramides Property Dualism Type Identity Theory Harry Frankfurt kalam John Hick FWD posse non peccare George Mavrodes epistemic distance theological universalism Wade Savage parasitic evil context of mystery Second theodicy Manichean Adam Ned paradox of the stone Dualism Bentham Block Boethius Euthyphro Dilemma privatio boni Augustine of Hippo omnipotenceGaunilo recapitulation Irenaeaus of Lyons Aquinas omniscience multiple realizability Wittgenstein Frank Jackson omnibenevolence Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia compossibility Philosophical zombie Edmund Gettier Robert Nozick maxim Zagzebski cognitivismnaturalism Norman Malcolm Categorical ImperativeFeuerbach Richard Swinburne Error TheoryCatharine Trotter Cockburn Marilyn Adams William Paley Mackie Midgley Chalmers Plantinga Aristotle Martha Nussbaum Diogenes Laertius AQA John Stuart MillFred Dretske MachiavelliHume’s Fork preference utilitarianism Bertrand Russell Peter Singer Epistemology solipsisSmarmt perception Logical Positivism Innatism Berkeleyan Idealism hypothetical imperative Hedonic Calculus tabula rasa paradox universalizability Proslogion BerkeleyUtility cogitohallucination Anselm cosmological Spinoza Time Indirect Realism Locke eudaimonia Demea Cleanthes Virtue Ethics SubstanceKantnecessary contingent Thomas Aquinas Dualism Thomas HobbesInteractionism Philo Leibniz Rationalism -

Cultural Expressions of Mind-Body Dualism

1 Susan Bordo FEMINISM, WESTERN CULTURE, AND THE BODY THE HEAVY BEAR "the withness of the body" Whitehead The heavy bear who goes with me, A manifold honey to smear his face, Clumsy and lumbering here and there, The central ton of every place, The hungry beating brutish one In love with candy, anger, and sleep, Crazy factotum, disheveling all, Climbs the building, kicks the football, Boxes his brother in the hate-ridden city. Breathing at my side, that heavy animal, That heavy bear who sleeps with me, Howls in his sleep for a world of sugar, A sweetness intimate as the water's clasp, Howls in his sleep because the tight-rope Trembles and shows the darkness beneath. The strutting show-off is terrified, Dressed in his dress-suit, bulging his pants, Trembles to think that his quivering meat Must finally wince to nothing at all. That inescapable animal walks with me, He's followed me since the black womb held, Moves where I move, distorting my gesture, A caricature, a swollen shadow, A stupid clown of the spirit's motive, Perplexes and affronts with his own darkness, The secret life of belly and bone, Opaque, too near, my private, yet unknown, Stretches to embrace the very dear With whom I would walk without him near, Touches her grossly, although a word Would bare my heart and make me clear, Stumbles, flounders, and strives to be fed Dragging me with him in his mouthing care, Amid the hundred million of his kind, The scrimmage of appetite everywhere. Delmore Schwartz Cultural Expressions of Mind-Body Dualism Through his metaphor of the body as "heavy bear," Delmore Schwartz vividly captures both the dualism that has been characteristic of Western philosophy and theology and its agonistic, unstable nature. -

Chapter VI : an Analysis of the Evangelistic Work Continued by the Church in Latin America Titulo Dussel, Enrique

Chapter VI : an analysis of the evangelistic work continued by the church in Latin Titulo America Dussel, Enrique - Autor/a; Autor(es) A history of the church in Latin America : colonialism to liberation (1492-1979) En: Michigan Lugar WM. B. Erdmans Publishing Editorial/Editor 1982 Fecha Colección Misiones religiosas; Colonialismo; Iglesia; Cristianismo; Religión; Historia; Temas Catolicismo; Indígenas; Sociología de la religión; América Latina; Capítulo de Libro Tipo de documento http://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/clacso/otros/20120223113421/7cap6.pdf URL Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.0 Genérica Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar 62 CHAPTER VI AN ANALYSIS OF THE EVANGELISTIC WORK CONTINUED BY THE CHURCH IN LATIN AMERICA We believe that the major difficulty in this type of value judgment is the lack of a comprehensive method that permits the consideration of the phenomenon in its totality and not merely in a single aspect. It is necessary, therefore, to review briefly certain elements outlined in the Introduction regarding methodology. All human communities have at certain times instruments that we regard as indi- cators of civilization. The same is true of a religion, especially the Roman Catholic faith. Religions maintain analogically a system of mediations, which we have designated as sacramentality, ecclesial corporality, the organizing instruments instituted by Jesus Christ in time, and the presence of his universal, salvific grace.