Cultural Expressions of Mind-Body Dualism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Worldviews*

RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEWS* SECULAR POLITICAL CHRISTIANITY ISLAM MARXISM HUMANISM CORRECTNESS Nietzsche/Rorty Sources Koran, Hadith Humanist Manifestos Marx/Engels/Lenin/Mao/ The Bible Foucault/Derrida, Frankfurt Sunnah I/II/ III Frankfurt School Subjects School Theism Theism Atheism Atheism Atheism THEOLOGY (Trinitarian) (Unitarian) PHILOSOPHY Correspondence/ Pragmatism/ Pluralism/ Faith/Reason Dialectical Materialism (truth) Faith/Reason Scientism Anti-Rationalism Moral Relativism Moral Absolutes Moral Absolutes Moral Relativism Proletariat Morality (foster victimhood & ETHICS (Individualism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) /Collectivism) Creationism Creationism Naturalism Naturalism Naturalism (Intelligence, Time, Matter, (Intelligence, Time Matter, ORIGIN SCIENCE (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) Energy) Energy) 1 Mind/Body Dualism Monism/self-actualization Socially constructed self Monism/behaviorism Mind/Body Dualism (fallen) PSYCHOLOGY (non fallen) (tabula rasa) Monism (tabula rasa) (tabula rasa) Traditional Family/Church/ Polygamy/Mosque & Nontraditional Family/statist Destroy Family, church and Classless Society/ SOCIOLOGY State State utopia Constitution Anti-patriarchy utopia Critical legal studies Proletariat law Divine/natural law Shari’a Positive law LAW (Positive law) (Positive law) Justice, freedom, order Global Islamic Theocracy Global Statism Atomization and/or Global & POLITICS Sovereign Spheres Ummah Progressivism Anarchy/social democracy Stateless Interventionism & Dirigisme Stewardship -

KNOWLEDGE ACCORDING to IDEALISM Idealism As a Philosophy

KNOWLEDGE ACCORDING TO IDEALISM Idealism as a philosophy had its greatest impact during the nineteenth century. It is a philosophical approach that has as its central tenet that ideas are the only true reality, the only thing worth knowing. In a search for truth, beauty, and justice that is enduring and everlasting; the focus is on conscious reasoning in the mind. The main tenant of idealism is that ideas and knowledge are the truest reality. Many things in the world change, but ideas and knowledge are enduring. Idealism was often referred to as “idea-ism”. Idealists believe that ideas can change lives. The most important part of a person is the mind. It is to be nourished and developed. Etymologically Its origin is: from Greek idea “form, shape” from weid- also the origin of the “his” in his-tor “wise, learned” underlying English “history.” In Latin this root became videre “to see” and related words. It is the same root in Sanskrit veda “knowledge as in the Rig-Veda. The stem entered Germanic as witan “know,” seen in Modern German wissen “to know” and in English “wisdom” and “twit,” a shortened form of Middle English atwite derived from æt “at” +witen “reproach.” In short Idealism is a philosophical position which adheres to the view that nothing exists except as it is an idea in the mind of man or the mind of God. The idealist believes that the universe has intelligence and a will; that all material things are explainable in terms of a mind standing behind them. PHILOSOPHICAL RATIONALE OF IDEALISM a) The Universe (Ontology or Metaphysics) To the idealist, the nature of the universe is mind; it is an idea. -

A Cardinal Sin: the Infinite in Spinoza's Philosophy

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Philosophy Honors Projects Philosophy Department Spring 2014 A Cardinal Sin: The nfinitI e in Spinoza's Philosophy Samuel H. Eklund Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/phil_honors Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Eklund, Samuel H., "A Cardinal Sin: The nfinitI e in Spinoza's Philosophy" (2014). Philosophy Honors Projects. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/phil_honors/7 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Cardinal Sin: The Infinite in Spinoza’s Philosophy By: Samuel Eklund Macalester College Philosophy Department Honors Advisor: Geoffrey Gorham Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without my advisor, Professor Geoffrey Gorham. Through a collaborative summer research grant, I was able to work with him in improving a vague idea about writing on Spinoza’s views on existence and time into a concrete analysis of Spinoza and infinity. Without his help during the summer and feedback during the past academic year, my views on Spinoza wouldn’t have been as developed as they currently are. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge the hard work done by the other two members of my honors committee: Professor Janet Folina and Professor Andrew Beveridge. Their questions during the oral defense and written feedback were incredibly helpful in producing the final draft of this project. -

Descartes' Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View

R ené Descartes (1596-1650) is generally regarded as the “father of modern philosophy.” He stands as one of the most important figures in Western intellectual history. His work in mathematics and his writings on science proved to be foundational for further development in these fields. Our understanding of “scientific method” can be traced back to the work of Francis Bacon and to Descartes’ Discourse on Method. His groundbreaking approach to philosophy in his Meditations on First Philosophy determine the course of subsequent philosophy. The very problems with which much of modern philosophy has been primarily concerned arise only as a consequence of Descartes’thought. Descartes’ philosophy must be understood in the context of his times. The Medieval world was in the process of disintegration. The authoritarianism that had dominated the Medieval period was called into question by the rise of the Protestant revolt and advances in the development of science. Martin Luther’s emphasis that salvation was a matter of “faith” and not “works” undermined papal authority in asserting that each individual has a channel to God. The Copernican revolution undermined the authority of the Catholic Church in directly contradicting the established church doctrine of a geocentric universe. The rise of the sciences directly challenged the Church and seemed to put science and religion in opposition. A mathematician and scientist as well as a devout Catholic, Descartes was concerned primarily with establishing certain foundations for science and philosophy, and yet also with bridging the gap between the “new science” and religion. Descartes’ Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View 1) Descartes’ disbelief in authoritarianism: Descartes’ belief that all individuals possess the “natural light of reason,” the belief that each individual has the capacity for the discovery of truth, undermined Roman Catholic authoritarianism. -

Expressions of Mind/Body Dualism in Thinspiration

MIND OVER MATTER: EXPRESSIONS OF MIND/BODY DUALISM IN THINSPIRATION Annamarie O’Brien A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2013 Committee: Dr. Marilyn Motz, Advisor Dr. Rebecca Kinney Dr. Jeremy Wallach © 2013 Annamarie O’Brien All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Marilyn Motz, Advisor Thinspiration images, meant to inspire weight-loss, proliferate online through platforms that encourage the circulation of user-generated content. Despite numerous alarmist critiques in mass media about thinspiration and various academic studies investigating ‘pro-anorexia’ sites, surprisingly little attention has been given to the processes of creation and the symbolic potential of thinspiration. This thesis analyzes the formal hybridity of thinspiration, and its use as an expressive medium. The particularities of thinspiration (including its visual characteristics, creative processes, and exhibition) may be considered carefully constructed instances of self- representation, hinging on the expression of beliefs regarding the mind and body. While these beliefs are deeply entrenched in popular body management discourse, they also tend to rely on traditional dualist ideologies. Rather than simply emphasizing slenderness or reiterating standard assumptions about beauty, thinspiration often evokes pain and sadness, and employs truisms about the transcendence of flesh and rebellion against social constraints. By harnessing individualist discourse and the values of mind/body dualism, thinspiration becomes a space in which people struggling with disordered eating and body image issues may cast themselves as active agents—contrary to the image of eating disorders proffered by popular and medical discourse. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank my thesis committee chair, Dr. -

PHI 110 Lecture 2 1 Welcome to Our Second Lecture on Personhood and Identity

PHI 110 Lecture 2 1 Welcome to our second lecture on personhood and identity. We’re going to begin today what will be two lectures on Rene Descartes’ thoughts on this subject. The position that is attributed to him is known as mind/body dualism. Sometimes it’s simply called the dualism for short. We need to be careful, however, because the word dualism covers a number of different philosophical positions, not always dualisms of mind and body. In other words, there are other forms of dualism that historically have been expressed. And so I will refer to his position as mind/body dualism or as Cartesian dualism as it’s sometimes also called. I said last time that Descartes is not going to talk primarily about persons. He’s going to talk about minds as opposed to bodies. But I think that as we start getting into his view, you will see where his notion of personhood arises. Clearly, Descartes is going to identify the person, the self, with the mind as opposed to with the body. This is something that I hoped you picked up in your reading and certainly that you will pick up once you read the material again after the lecture. Since I’ve already introduced Descartes’ position, let’s define it and then I’ll say a few things about Descartes himself to give you a little bit of a sense of the man and of his times. The position mind/body that’s known as mind/body dualism is defined as follows: It’s the view that the body is a physical substance — a machine, if you will — while the mind is a non-physical thinking entity which inhabits the body and is responsible for its voluntary movements. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Joan C. Callahan Professor Emerita Departments of Philosophy and Gender and Women’s Studies 1681 Leathers Road [email protected] Lawrenceburg, KY 40342 University of Kentucky 859-533-6863 Lexington, Kentucky 40506 Date: February 2014 Medical Leave 2008-2011 Retired March 2011 Areas of Specialization and Interest: Ethical Theory, Practical Ethics (including Biomedical Ethics, Professional Ethics, Ethics and Public Policy), Social and Political Philosophy, Feminism, Critical Race Theory, Philosophy of Law Higher Education: Ph.D. Philosophy: December 1982; University of Maryland, College Park M.A. Philosophy: December 1979; University of Maryland, College Park M.A. Humanities: June 1977; Simmons College B.A. Philosophy: June 1976; University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth Regular Positions: 2006-2007: Director, Gender and Women’s Studies Program, University of Kentucky 2004-2006: Director, Women’s Studies Program, University of Kentucky 1998-2003: Director, Women’s Studies Program, University of Kentucky 1995-present: Professor, Department of Philosophy; University of Kentucky 1988-1995: Associate Professor; Department of Philosophy; University of Kentucky 1986-1988: Assistant Professor; Department of Philosophy; University of Kentucky 1983-1986: Assistant Professor; Department of Philosophy; Louisiana State University 1982-1983: Instructor; Department of Philosophy; Louisiana State University Adjunct / Part-time / Other Positions: 2005-2011 Faculty Associate, Center for Bioethics, University of Kentucky 1994-2011: Graduate -

Is Plato a Perfect Idealist?

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 3, Ver. V (Mar. 2014), PP 22-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Is Plato a Perfect Idealist? Dr. Shanjendu Nath M. A., M. Phil., Ph.D. Associate Professor Rabindrasadan Girls’ College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Abstract: Idealism is a philosophy that emphasizes on mind. According to this theory, mind is primary and objective world is nothing but an idea of our mind. Thus this theory believes that the primary thing that exists is spiritual and material world is secondary. This theory effectively begins with the thought of Greek philosopher Plato. But it is Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) who used the term ‘idealism’ when he referred Plato in his philosophy. Plato in his book ‘The Republic’ very clearly stated many aspects of thought and all these he discussed from the idealistic point of view. According to Plato, objective world is not a real world. It is the world of Ideas which is real. This world of Ideas is imperishable, immutable and eternal. These ideas do not exist in our mind or in the mind of God but exist by itself and independent of any mind. He also said that among the Ideas, the Idea of Good is the supreme Idea. These eternal ideas are not perceived by our sense organs but by our rational self. Thus Plato believes the existence of two worlds – material world and the world of Ideas. In this article I shall try to explore Plato’s idealism, its origin, locus etc. -

Introduction to Philosophy

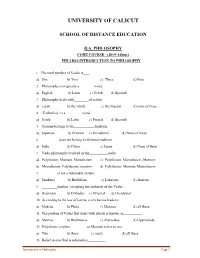

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. PHILOSOPHY CORE COURSE - (2019-Admn.) PHL1 B01-INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 1. The total number of Vedas is . a) One b) Two c) Three d) Four 2. Philosophy is originally a word. a) English b) Latin c) Greek d) Spanish 3. Philosophy deals with of reality. a) a part b) the whole c) the illusion d) none of these 4. ‘Esthetikos’ is a word. a) Greek b) Latin c) French d) Spanish 5. Taoism belongs to the tradition. a) Japanese b) Oriental c) Occidental d) None of these 6. does not belong to Oriental tradition. a) India b) China c) Japan d) None of these 7. Vedic philosophy evolved in the order. a) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism c) Polytheism, Monotheism, Monism b) Monotheism, Polytheism, monism d) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism 8. is not a heterodox system. a) Samkhya b) Buddhism c) Lokayata d) Jainism 9. implies ‘accepting the authority of the Vedas’. a) Heterodox b) Orthodox c) Oriental d) Occidental 10. According to the law of karma, every karma leads to . a) Moksha b) Phala c) Dharma d) all these 11. The portion of Vedas that deals with rituals is known as . a) Mantras b) Brahmanas c) Aranyakas d) Upanishads 12. Polytheism implies as Monism refers to one. a) Two b) three c) many d) all these 13. Belief in one God is referred as . Introduction to Philosophy Page 1 a) Henotheism b) Monotheism c) Monism d) Polytheism 14. Samkhya propounded . a) Dualism b) Monism c) Monotheism d) Polytheism 15. is an Oriental system. -

Virtue of Feminist Rationality

The Virtue of Feminist Rationality Continuum Studies in Philosophy Series Editor: James Fieser, University of Tennessee at Martin, USA Continuum Studies in Philosophy is a major monograph series from Continuum. The series features first-class scholarly research monographs across the whole field of philo- sophy. Each work makes a major contribution to the field of philosophical research. Aesthetic in Kant, James Kirwan Analytic Philosophy: The History of an Illusion, Aaron Preston Aquinas and the Ship of Theseus, Christopher Brown Augustine and Roman Virtue, Brian Harding The Challenge of Relativism, Patrick Phillips Demands of Taste in Kant’s Aesthetics, Brent Kalar Descartes and the Metaphysics of Human Nature, Justin Skirry Descartes’ Theory of Ideas, David Clemenson Dialectic of Romanticism, Peter Murphy and David Roberts Duns Scotus and the Problem of Universals, Todd Bates Hegel’s Philosophy of Language, Jim Vernon Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, David James Hegel’s Theory of Recognition, Sybol S.C. Anderson The History of Intentionality, Ryan Hickerson Kantian Deeds, Henrik Jøker Bjerre Kierkegaard, Metaphysics and Political Theory, Alison Assiter Kierkegaard’s Analysis of Radical Evil, David A. Roberts Leibniz Re-interpreted, Lloyd Strickland Metaphysics and the End of Philosophy, HO Mounce Nietzsche and the Greeks, Dale Wilkerson Origins of Analytic Philosophy, Delbert Reed Philosophy of Miracles, David Corner Platonism, Music and the Listener’s Share, Christopher Norris Popper’s Theory of Science, Carlos Garcia Postanalytic and Metacontinental, edited by James Williams, Jack Reynolds, James Chase and Ed Mares Rationality and Feminist Philosophy, Deborah K. Heikes Re-thinking the Cogito, Christopher Norris Role of God in Spinoza’s Metaphysics, Sherry Deveaux Rousseau and Radical Democracy, Kevin Inston Rousseau and the Ethics of Virtue, James Delaney Rousseau’s Theory of Freedom, Matthew Simpson Spinoza and the Stoics, Firmin DeBrabander Spinoza’s Radical Cartesian Mind, Tammy Nyden-Bullock St. -

Introduction to the Philosophy of Cognitive Science by Dr

Introduction to the Philosophy of Cognitive Science By Dr. Charles Wallis Last revision: 1/23/2013 Chapter 2 Greek Metaphysical Speculation: Philosophical Materialisms and Dualisms 2.1 Introduction It may seem odd to the contemporary thinker to suppose that people did not always have a clear conception of the mind and of mental phenomena. Nevertheless, like most contemporary western concepts the development of the notion of the mind and of mental phenomena actually occurs over the course of centuries. Indeed, the development of the notion of “the mind” arguably traces back to the development of the Greek notion of the soul. For most of Greek history the conception of the soul bears little resemblance to its contemporary western counterpart. In fact, the Greeks develop their notion of the soul as part of the development of general ontological frameworks for scientific and metaphysical speculation. Three features of the development of the Greek notion of the soul figure prominently in this rather superficial history. First, the development of the Greek notion of the soul represents a slow accretion of properties and processes associated with three different contemporary distinctions into a single ontological entity; living vs non-living, animate vs inanimate, and mental vs non-mental. Second, as the soul becomes more distinct both in its nature and in its functions, the Greeks begin to more actively debate whether the soul constitutes a fundamental kind of stuff (a distinct substance) or merely one of many permutations of more fundamental kinds of stuff (substances). For instance, early Greek thinkers often supposed that the universe consists of various permutations of one or more fundamental elements. -

Studia Culturologica Series

volume 22, autumn-winter 2005 studia culturologica series GEORGE GALE OSWALD SCHWEMMER DIETER MERSCH HELGE JORDHEIM JAN RADLER JEAN-MARC T~TAZ DIMITRI GINEV ROLAND BENEDIKTER Maison des Sciences de I'Homme et de la Societe George Gcrle LEIBNIZ, PETER THE GREAT, AND TIIE MOUERNIZAIION OF RUSSIA or Adventures of a Philosopher-King in the East Leibniz was the modern world's lirst Universal C'itizen. Ilespite being based in a backwater northern German principalit). Leibniz' scliolarly and diploniatic missions took liim - sometimes for extendud stays -- everywhere i~nportant:to Paris and Lotidon, to Berlin, to Vien~~nand Konie. And this in a time when travel \vas anything birt easy. Leibniz' intelluctual scope was ecli~ally\vide: his philosophic focus extended all the way ti-om Locke's England to Confi~cius'C'hina, even while his geopolitical interests encom- passed all tlie vast territory from Cairo to Moscow. In short, Leibniz' acti- vities, interests and attention were not in the least hounded by tlie narrow compass of his home base. Our interests, however, must be bounded: to this end, our concern in what follows will Iiniil itself to Leibniz' relations with tlie East, tlie lands beyond the Elbe, the Slavic lands. Not only are these relations topics of intrinsic interest, they have not received anywhere near tlie attention they deserve. Our focus will be the activities of Leibniz himself, the works of the living philosopher, diplomat, and statesman, as he carried them out in his own time. Althoi~ghLeibniz' heritage continues unto today in the form of a pl~ilosophicaltradition, exa~ninationoftliis aspect of Leibnizian influ- ence nli~stawait another day.