Locke and Leibniz on Perception*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Empiricism Locke, Berkeley and Hume

The British Empiricism Locke, Berkeley and Hume copyleft: nicolazuin.2018 | nowxhere.wordpress.com 1 The problem of knowledge • Please, look out of the window (or into the box, or just in front of you…) and answer the following questions: ‣ What do you see? ‣ Are you sure that what you see is what truly exists out there? ‣ What do you know about it? ‣ How do you know it? ‣ What make you sure of it? • Here you are: this is the problem of knowledge! • Now try to formalise it in a single question or definition. copyleft:nicolazuin.2018 | nowxhere.wordpress.com 1 A long way behind In a certain way, we could say that the problem of knowledge is the problem of philosophy itself, since its birth. • Think for example on this quotations: Parmenides: «the same thing is for thinking as is for being” Eraclitus: «The things of which there is sight, hearing, experience, I prefer». (But he also says: «Poor witnesses for men are their eyes and ears if they have barbarian souls» Gorgia: «Nothing exists; Even if something exists, nothing can be known about it; and Even if something can be known about it, knowledge about it can't be communicated to others. Even if it can be communicated, it cannot be understood». • Or try to imagine the discussion between Plato and Aristotle in the famous Raffaello’s School of Athens. • Now try to build a mind-map of all the different answers to the problem of knowledge given by the philosophers you already know copyleft:nicolazuin.2018 | nowxhere.wordpress.com 2 The terrible heritage of Descartes: The modern problem of knowledge originates from the conclusions of Descartes’s research, which was inspired by the successful advancement of geometry and natural sciences and was aimed to find a certain knowledge for philosophy. -

Perception Is Truth

Perception is Truth... WHEN IT COMES TO LEASING AND SHOPPING REPORTS What is the truth? This age old question has some very deep implications that go way beyond the point of this training tip. Yet, the question reminds us that two people can experience the same incident and walk away with completely different perceptions of what actually happened. Sometimes, just like beauty, "truth” is in the eye of the beholder. It is a matter of perception. Shopping report information is a vivid example of the fact that perception is reality. Occasionally, an EPMS shopper remembers a specific leasing presentation somewhat differently than the on-site professional who was shopped and later evaluated in a written format. The shopper reports that the leasing consultant was a bit distracted and indifferent, not very friendly, or “didn’t seem interested in meeting my needs”. Yet, that individual’s supervisor cannot believe that this very friendly and warm staff member could ever come across in any way but delightful, enthusiastic and professional! “Everyone loves her!” the supervisor explains. Sometimes the gap between what the leasing professional believes about her presentation and what the shopper describes comes down to perception. Regardless of what really (or not really!) happened, the perception of the shopper – and that of the typical rental prospect – is the only “truth” that really matters! Leasing is all about perception, isn’t it? Fellow onsite associates may say, “He is the friendliest guy you’ll ever meet! We love him!” But if this “friendliest guy” is perceived as unfriendly, to that prospect he is unfriendly! “You know, Sara is really nice once you get to know her!” This may be “true”; but the reality is the prospect is unlikely to spend enough time “getting to know” Sara to override their initial impression. -

Religious Worldviews*

RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEWS* SECULAR POLITICAL CHRISTIANITY ISLAM MARXISM HUMANISM CORRECTNESS Nietzsche/Rorty Sources Koran, Hadith Humanist Manifestos Marx/Engels/Lenin/Mao/ The Bible Foucault/Derrida, Frankfurt Sunnah I/II/ III Frankfurt School Subjects School Theism Theism Atheism Atheism Atheism THEOLOGY (Trinitarian) (Unitarian) PHILOSOPHY Correspondence/ Pragmatism/ Pluralism/ Faith/Reason Dialectical Materialism (truth) Faith/Reason Scientism Anti-Rationalism Moral Relativism Moral Absolutes Moral Absolutes Moral Relativism Proletariat Morality (foster victimhood & ETHICS (Individualism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) /Collectivism) Creationism Creationism Naturalism Naturalism Naturalism (Intelligence, Time, Matter, (Intelligence, Time Matter, ORIGIN SCIENCE (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) Energy) Energy) 1 Mind/Body Dualism Monism/self-actualization Socially constructed self Monism/behaviorism Mind/Body Dualism (fallen) PSYCHOLOGY (non fallen) (tabula rasa) Monism (tabula rasa) (tabula rasa) Traditional Family/Church/ Polygamy/Mosque & Nontraditional Family/statist Destroy Family, church and Classless Society/ SOCIOLOGY State State utopia Constitution Anti-patriarchy utopia Critical legal studies Proletariat law Divine/natural law Shari’a Positive law LAW (Positive law) (Positive law) Justice, freedom, order Global Islamic Theocracy Global Statism Atomization and/or Global & POLITICS Sovereign Spheres Ummah Progressivism Anarchy/social democracy Stateless Interventionism & Dirigisme Stewardship -

Studies on Collingwood, History and Civilization

Studies on Collingwood, History and Civilization Jan van der Dussen Studies on Collingwood, History and Civilization Jan van der Dussen Heerlen , The Netherlands ISBN 978-3-319-20671-4 ISBN 978-3-319-20672-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-20672-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015951386 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www. springer.com) Acknowledgements The following four essays are reproduced from their original publication. -

Perception and Law Enforcement

Perception and Law Enforcement Lt. Norman Hale White County Sheriff Department School of Law Enforcement Supervision Session XXXII Criminal Justice Institute Introduction Since the beginning, perception has been used by everyone. When man first said I am naked, I need clothing. The perception was I am naked. Without understanding why things are the way they appear man was fearful of the world around him. Superstitions overwhelmed man and his thoughts. It was an effort to explain the unexplainable. This is the perception of man and his surroundings. Early man worshiped nature in an attempt to change what was happening. At one time, it was believed that a man lived in the moon. This was based on the face seen on the moon. More resonantly, many believed there was or had been life on Mars, because of a photo taken as a satellite passed Mars showing a face on the surface (face on mars). This raised a large stir among people and the scientific community. It was not until some time later when a new photo was taken by a passing satellite, that the face on Mars proved to be a mountain and the face was formed by shadows cast across the surface of the mountain (face on mars). The attempt to understand how things are perceived goes back before the Egyptians were building pyramids. Modern man has devoted an extensive amount of time to studying perception and how it affects man. As the understanding of perception increases, the mystery that caused many superstitions is solved and man is no longer fearful. -

Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & The

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2015-4 Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime Andrew John Del Bene Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Ancient Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Del Bene, Andrew John, "Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime" (2015). Honors Bachelor of Arts. Paper 9. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/9 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime Andrew John Del Bene Honors Bachelor of Arts – Senior Thesis Project Director: Dr. Timothy Quinn Readers: Dr. Amit Sen & Dr. E. Paul Colella Course Director: Dr. Shannon Hogue I respectfully submit this thesis project as partial fulfillment for the Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree. I dedicate this project, and my last four years as an HAB at Xavier University, to my grandfather, John Francis Del Bene, who taught me that in life, you get out what you put in. Del Bene 1 Table of Contents Introduction — Philosophy and Economics, Ancients and Moderns 2 Chapter One — Aristotle: Politics 5 Community: the Household and the Πόλις 9 State: Economics and Education 16 Analytic Synthesis: Aristotle 26 Chapter Two — John Locke: The Two Treatises of Government 27 Community: the State of Nature and Civil Society 30 State: Economics and Education 40 Analytic Synthesis: Locke 48 Chapter Three — Aristotle v. -

Introduction to Philosophy

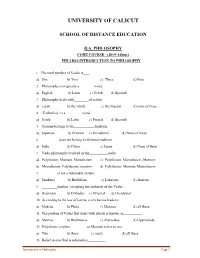

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. PHILOSOPHY CORE COURSE - (2019-Admn.) PHL1 B01-INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 1. The total number of Vedas is . a) One b) Two c) Three d) Four 2. Philosophy is originally a word. a) English b) Latin c) Greek d) Spanish 3. Philosophy deals with of reality. a) a part b) the whole c) the illusion d) none of these 4. ‘Esthetikos’ is a word. a) Greek b) Latin c) French d) Spanish 5. Taoism belongs to the tradition. a) Japanese b) Oriental c) Occidental d) None of these 6. does not belong to Oriental tradition. a) India b) China c) Japan d) None of these 7. Vedic philosophy evolved in the order. a) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism c) Polytheism, Monotheism, Monism b) Monotheism, Polytheism, monism d) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism 8. is not a heterodox system. a) Samkhya b) Buddhism c) Lokayata d) Jainism 9. implies ‘accepting the authority of the Vedas’. a) Heterodox b) Orthodox c) Oriental d) Occidental 10. According to the law of karma, every karma leads to . a) Moksha b) Phala c) Dharma d) all these 11. The portion of Vedas that deals with rituals is known as . a) Mantras b) Brahmanas c) Aranyakas d) Upanishads 12. Polytheism implies as Monism refers to one. a) Two b) three c) many d) all these 13. Belief in one God is referred as . Introduction to Philosophy Page 1 a) Henotheism b) Monotheism c) Monism d) Polytheism 14. Samkhya propounded . a) Dualism b) Monism c) Monotheism d) Polytheism 15. is an Oriental system. -

Studia Culturologica Series

volume 22, autumn-winter 2005 studia culturologica series GEORGE GALE OSWALD SCHWEMMER DIETER MERSCH HELGE JORDHEIM JAN RADLER JEAN-MARC T~TAZ DIMITRI GINEV ROLAND BENEDIKTER Maison des Sciences de I'Homme et de la Societe George Gcrle LEIBNIZ, PETER THE GREAT, AND TIIE MOUERNIZAIION OF RUSSIA or Adventures of a Philosopher-King in the East Leibniz was the modern world's lirst Universal C'itizen. Ilespite being based in a backwater northern German principalit). Leibniz' scliolarly and diploniatic missions took liim - sometimes for extendud stays -- everywhere i~nportant:to Paris and Lotidon, to Berlin, to Vien~~nand Konie. And this in a time when travel \vas anything birt easy. Leibniz' intelluctual scope was ecli~ally\vide: his philosophic focus extended all the way ti-om Locke's England to Confi~cius'C'hina, even while his geopolitical interests encom- passed all tlie vast territory from Cairo to Moscow. In short, Leibniz' acti- vities, interests and attention were not in the least hounded by tlie narrow compass of his home base. Our interests, however, must be bounded: to this end, our concern in what follows will Iiniil itself to Leibniz' relations with tlie East, tlie lands beyond the Elbe, the Slavic lands. Not only are these relations topics of intrinsic interest, they have not received anywhere near tlie attention they deserve. Our focus will be the activities of Leibniz himself, the works of the living philosopher, diplomat, and statesman, as he carried them out in his own time. Althoi~ghLeibniz' heritage continues unto today in the form of a pl~ilosophicaltradition, exa~ninationoftliis aspect of Leibnizian influ- ence nli~stawait another day. -

Locke, Kant, and Synthetic a Priori Cognition

Brian A. Chance Locke, Kant, and Synthetic APriori Cognition Abstract: This paper attempts to shed light on threerelated issues that bear di- rectlyonour understandingofLockeand Kant.The first is whether Kant believes Lockemerelyanticipates his distinction between analytic and synthetic judg- ments or also believes Lockeanticipateshis notion of synthetic apriori cogni- tion. The second is what we as readers of Kant and Lockeshould think about Kant’sview whatever it turnsout to be, and the third is the nature of Kant’sjus- tification for the comparison he drawsbetween his philosophyand Locke’s. I argue(1) that Kant believes Lockeanticipates both the analytic-synthetic distinc- tion and Kant’snotion of synthetic apriori cognition, (2)thatthe best justifica- tion for Kant’sclaim drawsonLocke’sdistinction between trifling and instruc- tive knowledge,(3) that the arguments against this claim developed by Carson, Allison, and Newman fail to undermine it,and (4) that Kant’sown jus- tification for his claim is quite different from what manycommentators have thoughtitwas (or should have been). Introduction Kant’srelationship to his empiricist predecessors is complex, and this complex- ity is perhaps no more evident than in the caseofLocke, whose philosophyin- fluenced not onlythe likes of Berkeley,Hume, and Reid but alsoageneration of Kant’sGermanpredecessors.¹ The “famous Locke” is the first philosopher Kant mentionsinthe Critique of Pure Reason (CPR), but he is also critical of Locke’s “physiology of the human understanding” and contrasts his transcendental de- Citations from the Critique of Pure Reason use the standardA/B formattorefer to the pagesof the first (A) and second (B) editions. Citations from Kant’sother worksuse the volume number and pagination of KantsgesammelteSchriften,edited by the Royal Prussian(laterGerman, then Berlin-Brandenburg) Academy of the Sciences. -

Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/10/2011, SPi 3 Perceptual Causality, Counterfactuals, and Special Causal Concepts Johannes Roessler On one view, an adequate account of causal understanding may focus exclusively on what is involved in mastering general causal concepts (concepts such as ‘x causes y’ or ‘p causally explains q’). An alternative view is that causal understanding is, partly but irreducibly, a matter of grasping what Anscombe called special causal concepts, con- cepts such as ‘push’, ‘flatten’,or‘knock over’. We can label these views generalist vs particularist approaches to causal understanding. It is worth emphasizing that the contrast here is not between two kinds of theories of the metaphysics of causation, but two views of the nature and perhaps source of ordinary causal understanding. One aim of this paper is to argue that it would be a mistake to dismiss particularism because of its putative metaphysical commitments. I begin by formulating an intuitively attractive version of particularism due to P.F. Strawson, a central element of which is what I will call na¨ıve realism concerning mechanical transactions. I will then present the account with two challenges. Both challenges reflect the worry that Strawson’s particularism may be unable to acknowledge the intimate connection between causa- tion and counterfactuals, as articulated by the interventionist approach to causation. My project will be to allay these concerns, or at least to explore how this might be done. My (tentative) conclusion will be that Strawson’sna¨ıve realism can accept what interventionism has to say about ordinary causal understanding, and that intervention- ism should not be seen as being committed to generalism. -

Unity of Mind, Temporal Awareness, and Personal Identity

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE THE LEGACY OF HUMEANISM: UNITY OF MIND, TEMPORAL AWARENESS, AND PERSONAL IDENTITY DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Philosophy by Daniel R. Siakel Dissertation Committee: Professor David Woodruff Smith, Chair Professor Sven Bernecker Associate Professor Marcello Oreste Fiocco Associate Professor Clinton Tolley 2016 © 2016 Daniel R. Siakel DEDICATION To My mother, Anna My father, Jim Life’s original, enduring constellation. And My “doctor father,” David Who sees. “We think that we can prove ourselves to ourselves. The truth is that we cannot say that we are one entity, one existence. Our individuality is really a heap or pile of experiences. We are made out of experiences of achievement, disappointment, hope, fear, and millions and billions and trillions of other things. All these little fragments put together are what we call our self and our life. Our pride of self-existence or sense of being is by no means one entity. It is a heap, a pile of stuff. It has some similarities to a pile of garbage.” “It’s not that everything is one. Everything is zero.” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche “Galaxies of Stars, Grains of Sand” “Rhinoceros and Parrot” ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I: Hume’s Appendix Problem and Associative Connections in the Treatise and Enquiry §1. General Introduction to Hume’s Science of Human Nature 6 §2. Introducing Hume’s Appendix Problem 8 §3. Contextualizing Hume’s Appendix Problem 15 §4. -

Philosophy.Pdf

Philosophy 1 PHIL:1401 Matters of Life and Death 3 s.h. Contemporary ethical controversies with life and death Philosophy implications; topics may include famine, brain death, animal ethics, abortion, torture, terrorism, capital punishment. GE: Chair Values and Culture. • David Cunning PHIL:1636 Principles of Reasoning: Argument and Undergraduate major: philosophy (B.A.) Debate 3 s.h. Undergraduate minor: philosophy Critical thinking and its application to arguments and debates. Graduate degrees: M.A. in philosophy; Ph.D. in philosophy GE: Quantitative or Formal Reasoning. Faculty: https://clas.uiowa.edu/philosophy/people/faculty PHIL:1861 Introduction to Philosophy 3 s.h. Website: https://clas.uiowa.edu/philosophy/ Varied topics; may include personal identity, existence of The Department of Philosophy offers programs of study for God, philosophical skepticism, nature of mind and reality, undergraduate and graduate students. A major in philosophy time travel, and the good life; readings, films. GE: Values and develops abilities useful for careers in many fields and for any Culture. situation requiring clear, systematic thinking. PHIL:1902 Philosophy Lab: The Meaning of Life 1 s.h. Further exploration of PHIL:1033 course material with the The department also administers the interdisciplinary professor in a smaller group. undergraduate major in ethics and public policy, which it offers jointly with the Department of Economics and the PHIL:1904 Philosophy Lab: Liberty and the Pursuit of Department of Sociology and Criminology; see Ethics and Happiness 1 s.h. Public Policy in the Catalog. Further exploration of PHIL:1034 course material with the professor in a smaller group. Programs PHIL:1950 Philosophy Club 1-3 s.h.