Palmer, Ronald D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remarks of Senator Bob Dole

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Remarks of Senator Bob Dole AMERICAN TASK FORCE FOR LEBANON AWARDS DINNER Los Angeles, February 3, 1990 I AM TRULY HONORED TO RECEIVE THE PHILIP C. HABIB AWARD. IT HAPPENS THAT A MEMBER OF MY STAFF ONCE WORKED FOR PHIL HABIB --AL LEHN, HE'S HERE WITH ME TONIGHT. WHEN AL CAME TO WORK FOR ME, I WARNED HIM: GET READY FOR LONG HOURS, LOW PAY, NO PRAISE, AND PLENTY OF FLAK. HIS REPLY WAS: I AM READY -- I USED TO WORK FOR PHIL HABIB. Page 1 of 55 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 2 SO I DO APPRECIATE AN AWARD BEARING THIS DISTINGUISHED NAME. l'M ALSO HONORED TO BE FOLLOWING IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF LAST YEAR'S RECIPIENT, SENATE MAJORITY LEADER GEORGE MITCHELL. HE'S A GREAT DEMOCRAT --1 HAPPEN TO BE A REPUBLICAN. EACH OF US IS PROUD OF OUR PARTY -- AND I --ADMIT IT: I WANT HIS JOB -- MAJORITY LEADER. Page 2 of 55 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 3 BUT ANY PARTISANSHIP WE HAVE IS TEMPERED BY A REAL FRIENDSHIP, AND BY MUTUAL RESPECT. AND WHEN IT COMES TO THE ISSUE OF LEBANON, GEORGE MITCHELL AND BOB DOLE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN, AND WILL CONTINUE TO BE, OF ONE MIND. 0 LIKE MANY OF YOU, l'VE COME A LONG WAY TO ATIEND TONIGHT'S DINNER. -

Since Aquino: the Philippine Tangle and the United States

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 6 - 1986 (77) SINCE AQUINO: THE PHILIPPINE • TANGLE AND THE UNITED STATES ••' Justus M. van der Kroef SclloolofLAw UNivERsiTy of o• MARylANd. c:. ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Acting Managing Editor: Shaiw-chei Chuang Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. -

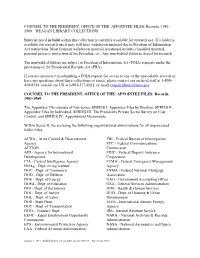

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept. -

394279-395299 Box: 152

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: WHORM Subject Files Folder Title: CO 125 (Philippines) 394279-395299 Box: 152 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ !;,• 39431-4 ID #.'----------- WHITE HOUSE CORRESPONDENCE TRACKING WORKSHEET 0 0 • OUTGOING 0 H · INTERNAL ~ I · INCOMING Date Correspondence I (} "? /. ;{ cJ Recelved(YY/MM/DD) ---""-·8 6 -~"'"---""'------ Name of Correspondent: ""'l.,/-:-Z=M=r-=-. =/7if-'M=r=s=·~/:1-Zi-=-M=i=s=s,___----'/;-'!/._e_/c_c_h__ ~__ ll_/._1_T_A ______ _ D Ml Mail Report UserCodes: (A) (B)"'----- (C) ___ Subject: fa/~~(}~ ~J ~~ ,·/ ,.., /7 ~ ,, ~- ·;.- /},,..,"_ ~ • ~ .t/-). ~ /r0.Ar ~(YJ ~ • . ROUTE TO: ACTION · DISPOSITION Tracking Type Completion Action Date of Date ·office/Agency (Staff Name) Code YYfMM/DD Response Code YY/MM/DD CoCoza ORIGINATOR 86 I Q310V).~_,. ___"_· ___ a a6103)/ 2-..f Referral Note: Id- as: J030fo 't~_--___ fl a& 10:31 :i. ~ Referral Note: Referral Note: .· Referral Note: Referral Note: ACTION CODES: DISPOSITION CODES: A - Appropriate Action I • Info Copy Only/No Action Necessary A • Answered C • Completed C - Comment/Recommendation R • Direct Reply w/Copy B • Non-Special Referral S • Suspended D • Draft Response S • For Signature F • Furnish Fact Sheet X • Interim Reply to be used as Enclosure FOR OUTGOING CORRESPONDENCE: Type of Response = Initials of Signer Code = "A" Completion Date = Date of Outgoing Keep this worksheet attached to the original incoming letter. -

Bay State Blamed for 1-84 Delay

f'«t«>4ta»-(»r /*« W**»«i»**r*«. C^lK H.' v J hi. ^ ^ t r » ^k*« f WM>vtir>M>’'r^ '» I ' ' ' ' "-r 24 - MANCHESTER HEaiALD. Wed.. July M. IBtt ;^hiWri \ Public Records PQW plates bring Weicker's win Waranty deeds Manchester, property on S. 748 Tolland Turnpike and at 25 back memories Reagan's loss - Vernon Street Corp. to Joseph E. Lakewood Circle. Thayer Road, $1,0W. Connor and Mary B. Connor, proper ty at 224 Knollwood Road, 4126,250. Attachment Trade name certificates . page 11 . page 6 St. Bartholomew Church Corp. to Glastonhury Lumber Co. against Robert E. Brown doing business David I. Kay and Andy L. .Kay, Woodhaven Builders, lots In Blue as Memorial Comer Store. property at 741 E. Middle Turnpike, Trail Estates, $7,000. David E. Cormier doing business 170,000. St. Francis Hospital and Medical as David Cormier Carpentry, 41 Merritt N. Baldwin to William M. Center against Gloria Gouin, Fairview St. M Carroll, property on Still Field property on Henry Street, $2,150. Diane M. Wliite doing business as Road, $23,000. Able Weights, 15 Phelps St. Suffolk Management Co. Inc. to Kathleen A. Liappes, 3 Riga Lane, Miriam Gants, Unit 529C Northwood Bolton, doing business as Early Manchester, Conn. ToWnhouses, Hilliard Street, $54,- LIs pendens Morning Paper Service. Clear tonight, 800. Heritage Savings and Loan Angeline Ponticelli to Robert J. Thursday, July 29, 1982 Association against Woodhaven sunny Friday Gouin and Judith K. Gouin, property Dissolution of trade name Builders Inc. et als, foreclosure on Single copy 25tp at 31-33 Willard Road, $51,900. -

WHORM Subject Files Folder Title:CO 125 (Philippines) 395300-397999

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: WHORM Subject Files Folder Title: CO 125 (Philippines) 395300-397999 Box: 152 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ -- 3953'52 LEONARD & McGuAN, P.C. ATTORNEYS AT LAW SUITE 1020 ( 202) 872-10:95 JERRIS l.E<f11!:tR12 'i THE FARRAGUT BUILDING 8 :\ TELEX, 904059WSH JAMES T. DEVINE KATHLEEN HEENAN McGUAN 900 SEVENTEENTH STREET, N.W. DANIEL J. McGUAN WASHINGTON, D.C. 20006 WILLIAM W. NICKERSON ¥bt/10 February 26, 1986 t'CJldS- Honorable Don Regan Chief of Staff to the President of the United States //2tJ03 The White House Washington, D.C. 20500 ~a; I Dear Don: I n,~.::r.:e.g.ard.rr~,t.Q.._t;.b,,,~~l:l~.g,~§Js,.ll~E~t.-X..~.-1!!~.EJ t . ~he old Navy phrase, "Well Done. 11 ·· ~~~,. ... ,,,,,_.,,..... C~·-~-"-·,,~··~"···~. ·-···- ~... ~. ...., ......... ...._...... '.".,..;: .. ~..,.,_-----~-,,'!-:-.-;·"-'" _._,..._ Good Luck, i./"7 ~(._~ ~-lm Devine JD/ch THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON TO: FROM: DONALDT.REGAN \ CHIEF OF STAFF , ~ NSC 1144 / United States Department of S~~te JVashington, D.C. 20520 396190 /~ c!?J/~ February 11, 1986 -------~""'~-- g~~/ MEMORANDUM FOR VADM JOHN M. POINDEXTER ~t?b7J, THE WHITE HOUSE Subject: Questions and Answers Concerning The Philippines As requested, we are hereby providing g_ue~tion~_ and answers co~9erning the Philippines • ........-=~..._.,,..-,.__,-;,;;·cl:",S;.'1>...,..,;;;::,,;,.~;-~,~~;,.,,;.o:.:,.~• ._~:;_.""',_o,.""3,;;<4<;;;"'"-R.;!f'l±-·~JiL$:::a_~-z;;;-,,;<:....,·~ Attachment: Questions and Answers Concerning The Philippines THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON February 12, 1986 FOR: SECRETARIAT FROM: BAERBEL See Karna's notation at the bottom of the profile sheet. -

Ang Rebolusyong Pilipino: Isang Pagtanaw Mula Sa Loob

ANG REBOLUSYONG PILIPINO: ISANG PAGTANAW MULA SA LOOB Unang Kabanata Mga Taon ng Pagbubuo Mga Bagay-bagay Hinggil sa Kapanganakan T1: Kailan at saan ka ipinanganak? Maaari bang ilahad mo sa amin ang ilang bagay tungkol sa pinagmulan ng iyong pamilya? Sinu-sino ang iyong mga magulang? Ano ang katayuang panlipunan ng iyong pamilya? S: Ipinanganak ako noong Pebrero 8, 1939 sa Cabugao, Ilocos Sur sa Hilagang Luzon. Ang aking amang si Salustiano Serrano Sison ay namatay noong 1958 sa gulang na limampu't siyam na taon. Ang aking inang si Florentina Canlas ay mahigit na walumpung taon na ngayon. Ang aking pamilya ay kabilang sa uring panginoong maylupa at siyang prinsipal na pamilyang pyudal sa aking bayan. Ang aking ama ay kabilang sa ikatlong henerasyon ng ninunong lalaki ng pamilya, si Don Leandro Serrano, na nakapag- ipon ng pinakamalawak na lupain sa Hilagang Luzon noong huling kwarto ng ikalabinsiyam na siglo. Ang aking lolo sa ama, si Don Gregorio Sison, ang kahuli-hulihang gobernadorsilyo (punong ehekutibo ng isang munisipyo) noong kolonyal na rehimeng Espanyol at kauna-unahang presidente munisipal sa ilalim ng kolonyal na paghahari ng Estados Unidos. Hinawakan niya ang posisyong ito hanggang sa kamatayan niya noong maagang bahagi ng dekadang treynta. Ang pinagbuklod na mga pamilyang Serrano at Sison ay nangibabaw sa ekonomya at pulitika sa buong probinsya ng Ilocos Sur hanggang noong dekadang kwarenta. Minsan ay dalawa sa mga tiyo ko, sina Jesus Serrano at Sixto Brillantes, ang panabay na naging konggresista ng dalawang distrito ng aking probinsya. Isang lolo ko, si Don Mena Crisologo, ang naging unang gobernadorsilyo sa ilalim ng kolonyal na rehimeng Amerikano. -

Interview with Ronald D. Palmer

Library of Congress Interview with Ronald D. Palmer The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR RONALD D. PALMER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 15, 1992 Copyright 1998 ADST Q: This is May 15, 1990. This is an interview with Ambassador Ronald D. Palmer at his office at George Washington University. The interview is being done on behalf of the Foreign Affairs Oral History Program and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. Mr. Ambassador I wonder if you would give me something about your background—where you come from, where you were educated, etc.? PALMER: I am from southwestern Pennsylvania. My father's family comes from Fayette County and my mother's family from Westmoreland County. My paternal grandmother's family is from German Township which, as the name implies, was settled by Germans. Her family dates from 1760 in the region, my mother's family comes from Fauquier County in Virginia and settled in Pennsylvania in about 1900. I was actually born in Uniontown, Pennsylvania. This was an area through which the Underground Railroad went from the early part of the 19th century until the end of the Civil War. Of course, some people say that the Underground Railroad did not exist until it was officially declared to exist by William Lloyd Garrison or someone like that. Q: But it had to have been going for a much longer time. Interview with Ronald D. Palmer http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000896 Library of Congress PALMER: Oh, quite, quite. I think I may have mentioned that I have been doing some family history research and it is quite interesting to see the waxing and waning of the black population. -

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Reagan Dedicates New Facility in Grenada Aquino Dismisses Suggestion for a New Election

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Vol. 42 -- No. 34 -- U.S. Navy's only shore-based daily newspaper -- Thursday, Feb. 20, 1986 Reagan dedicates new facility in Grenada cost of $20 million. Reagan presidential motorcade will President Reagan *e es) today-- to Grenada, the also will place a wreath on a take from the airport to St. Around the globe tiny Caribbean island whose monument to the 19 Americans George's, the nation's Marxist government was who died during the invasion. capital. overthrown by the U.S.-led Other highlights include a invasion in October 1983. mini-summit with East Followers of the New Jewel During his four-and-a-half Caribbean leaders. Movement, which was ousted in Chief Of Heart Surgery Ends Testimony (UPI) -- hour visit, the president Grenada is rolling out the the invasion, have planned an Navy Cdr. Donal Billig ended five days of testimony, will dedicate the new point welcome mat for Reagan. anti-Reagan rally, about insisting he is innocent of involuntary manslaughter Salines International Streets were cleaned and one-half mile from where the and dereliction of duty. Billig is accused in the Airport. The facility was decorated with flowers, the president will address deaths of five patients at Bethesda Naval Hospital, begun by Cubans and completed harbor dredged and fences Grenadians. where he was chief of heart surgery. by the United States at a painted along the route the Painting Discovered Hear Pecos River (UPI) -- Texas A and M University archaeologists say a 17-inch cave painting depicting a comet has been discovered Aquino dismisses suggestion for a new election near the headwaters of the Pecos River. -

Redalyc.A UNIVERSALIST HISTORY of the 1987 PHILIPPINE

Historia Constitucional E-ISSN: 1576-4729 [email protected] Universidad de Oviedo España Desierto, Diane A. A UNIVERSALIST HISTORY OF THE 1987 PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION (I) Historia Constitucional, núm. 10, septiembre, 2009, pp. 383-444 Universidad de Oviedo Oviedo, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=259027582013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative A UNIVERSALIST HISTORY OF THE 1987 PHILIPPINE 1 CONSTITUTION (I) Diane A. Desierto2 “To be non-Orientalist means to accept the continuing tension between the need to universalize our perceptions, analyses, and statements of values and the need to defend their particularist roots against the incursion of the particularist perceptions, analyses, and statements of values coming from others who claim they are putting forward universals. We are required to universalize our particulars and particularize our universals simultaneously and in a kind of constant dialectical exchange, which allows us to find new syntheses that are then of course instantly called into question. It is not an easy game.” - Immanuel Wallerstein in EUROPEAN UNIVERSALISM: The Rhetoric of Power3 “Sec.2. The Philippines renounces war as an instrument of national policy, adopts the generally accepted principles of international law as part of the law of the land and adheres to the policy of peace, equality, justice, freedom, cooperation, and amity with all nations. Sec. 11. The State values the dignity of every human person and guarantees full respect for human rights.” - art. -

02-25-1920 Philip Habib.Indd

This Day in History… February 25, 1920 Happy Birthday, Philip Habib American diplomat Philip Charles Habib was born on February 25, 1920, in Brooklyn, New York. He was a respected peace negotiator and special envoy for 30 years and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his life’s work. After graduating from high school, Habib worked as a shipping clerk. He then went on to study forestry at the University of Idaho. He graduated in 1942 and shortly after joined the US Army to serve From the Distinguished American Diplomats Issue in World War II. Habib eventually reached the rank of captain before being discharged in 1946. Using his G.I. Bill, Habib went to the University of California to get a Ph.D. in agricultural economics. When Habib was a student at the University of California, recruiters for the US Foreign Service visited the school. Habib had never considered a career in diplomacy, but he enjoyed the challenge of taking tests. He ended up scoring in the top 10% on the Foreign Service Exam and decided to follow that career path. Starting in 1949, Habib took assignments in Canada, New Zealand, and South Korea. By 1965, he was the chief political advisor to Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge and was serving in Vietnam. Habib studied how the war was affecting the country and convinced President Lyndon Johnson to decrease his bombing of North Vietnam. Habib then went on to serve as the US ambassador to South Korea from 1971 to 1974 and assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific affairs from 1974 to 1976. -

President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary, September 1-30, 1969

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/1/1969 A Appendix “C” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/8/1969 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-3 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary September 1, 1969 – September 30, 1969 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) \~"'lt:t: (raVel KCCOru tor lravel f\CUVHY, IPLACE DAY BEGA:" DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) i S~l?_'IEMBER 1, 1969 iTHE WESTERN WHITE HOUSE TlME DAY lSAN CLEMENTE, CAliFORNIA 9 :46 am MONDAY ACTIVITY Lo LD , 9:46 9 :48 The President went to his office. , The President met with: 9:50 10:01 John D. Ehrlichman, Counsel 9:54 9:56 Henry A. Kissinger, Assistant [10:10 The President met with: Walter H. Wheeler, Jr., President of United Community Funds and Councils of America,Inc., 1 10:20 10 :32 The President went to the Conference Room for the Filming of a United Fund Statement.