Painting in Flanders After 1980 (ENG)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raoul De Keyser: Drift Online

esq96 [Download] Raoul De Keyser: Drift Online [esq96.ebook] Raoul De Keyser: Drift Pdf Free Ulrich Loock ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #993691 in Books 2016-04-26Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.00 x .50 x 7.60l, .0 #File Name: 1941701280112 pages | File size: 41.Mb Ulrich Loock : Raoul De Keyser: Drift before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Raoul De Keyser: Drift: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy Mary BianchiA beautiful book from a wonderful show. An undervalued painter0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy Paulo A. Laportgorgeous lesson of life.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy SDA clean and simple book to show beautiful work. Love the look and feel. Raoul De Keyser: Drift, published on the occasion of the eponymous show curated by Ulrich Loock at David Zwirner, is organized around a group of 23 paintings that De Keyser (1930ndash;2012) completed shortly before his death, which have become known collectively as The Last Wall. Imposing stark material and formal limitations, De Keyser was able to revisit in this body of work many of the major themes that occupied him throughout his nearly 50-year career: inconspicuous things close at hand, the landscape of the low lands where he lived all his life and the partition of the picture plane. This elegant catalogue presents plates and details of a selection of paintings, beginning in the 1970s, that emphasizes the tentative way De Keyser chose to explore his themes. -

Import Page 1

import Exposition A. Renoir. (Paris), Galeries Durand-Ruel, Mai 1892. In-8°. 48 gen.pp. Ex. op Japans papier, met drie etsen. Orig. half oranje mar. band met hoeken, afgeboord met dubbele vergulde filets, rug op vijf ribben. Schitterend exemplaar. Bijgevoegd: Paul Verlaine, Femmes. Imprimé sous le manteau et ne se vend nulle part. Een van de 480 ex. op Van Gelder, nr. 134. Ingenaaid onder orig. omslag. <br/><br/>PIERRE-AUGUSTE RENOIR (1841-1919) Ex. sur Japon, contenant trois eaux-fortes. Rel. orig. en demi-mar. orange à coins. On y joint: Paul Verlaine, Femmes. Imprimé sous le manteau et ne se vend nulle part. Tir. lim. et num. à la main, un des 480 ex. sur Van Gelder, nr. 134. Broché sous couv. originale. <br/><br/>PIERRE-AUGUSTE RENOIR (1841-1919) Exposition A. Renoir. (Paris), Galeries Durand- Ruel, Mai 1892. In-8°. 48 gen.pp. Ex. op Japans papier, met drie etsen. Orig. half oranje mar. band met hoeken, afgeboord met dubbele vergulde filets, rug op vijf ribben. Schitterend exemplaar. Bijgevoegd: Paul Verlaine, Femmes. Imprimé PIERRE-AUGUSTE sous le manteau et ne se vend nulle part. Een van de 480 ex. 1000 RENOIR (1841-1919) op Van Gelder, nr. 134. Ingenaaid onder orig. omslag. 200 250 (Emile Claus) C. Lemonnier, Emile Claus. Brussel, Van Oest, 1908. In-4°. 71 gen.pp. Een van de 50 luxe ex. op Japans, met originele litho "Hiver". Ingenaaid onder orig. kaft. <br/><br/>EMILE CLAUS (1849-1924) Lithographie originale "Hiver". Dans ex. de tête sur Japon, nr. 23. Broché sous couv. originale. -

Translated and Edited Publications

Translated and edited publications There are nearly 250 items in this list, including co-translations and revised editions. Editing and translations from German and French are indicated, otherwise the listed publications are translations from Dutch. Katrijn Van Bragt and Sven Van Dorst, Study of a Young Woman: An exceptional glimpse into Michaelina Wautier’s studio (1604–1689) (Phoebus Focus 19) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Leen Kelchtermans, Portrait of Elisabeth Jordaens: Jacob Jordaens’ (1593–1678) tribute to his eldest daughter and country life (Phoebus Focus 18) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Nils Büttner, A Sailor and a Woman Embracing: Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and modern painting (Phoebus Focus 16) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Dina Aristodemo, Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi: Lodovico Guicciardini and the Low Countries (Phoebus Focus 15) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Timothy De Paepe, Elegant Company in a Garden: A musical painting full of sixteenth-century wisdom (Phoebus Focus 9) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2020) Chris Stolwijk and Renske Cohen Tervaert, Masterpieces in the Kröller- Müller Museum (Otterlo: Kröller-Müller Museum, 2020) Maximiliaan Martens et al., Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution (Antwerp: Hannibal, 2020). All the translations from Dutch. Nienke Bakker and Lisa Smit (eds.), In the Picture: Portraying the Artist (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2020) Hans Vlieghe, Apollo on His Sun Chariot (Phoebus Focus 8) (Antwerp: The Phoebus Foundation, 2019) Joris Van Grieken, Maarten Bassens, et al., Bruegel in Black & White: The World of Bruegel (Antwerp: Hannibal, 2019). Translation of all but one of the texts. Bert van Beneden (ed.) From Titian to Rubens: Masterpieces from Antwerp and other Flemish Cities (Ghent: Snoeck, 2019); exhibition catalogue Venice, Palazzo Ducale. -

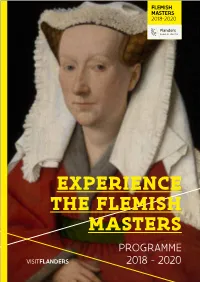

Experience the Flemish Masters Programme 2018 - 2020

EXPERIENCE THE FLEMISH MASTERS PROGRAMME 2018 - 2020 1 The contents of this brochure may be subject to change. For up-to-date information: check www.visitflanders.com/flemishmasters. 2 THE FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 AT THE PINNACLE OF ARTISTIC INVENTION FROM THE MIDDLE AGES ONWARDS, FLANDERS WAS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE FAMOUS ART MOVEMENTS OF THE TIME: PRIMITIVE, RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE. FOR A PERIOD OF SOME 250 YEARS, IT WAS THE PLACE TO MEET AND EXPERIENCE SOME OF THE MOST ADMIRED ARTISTS IN WESTERN EUROPE. THREE PRACTITIONERS IN PARTICULAR, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL AND RUBENS ROSE TO PROMINENCE DURING THIS TIME AND CEMENTED THEIR PLACE IN THE PANTHEON OF ALL-TIME GREATEST MASTERS. 3 FLANDERS WAS THEN A MELTING POT OF ART AND CREATIVITY, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, AND STILL TODAY IS A REGION THAT BUSTLES WITH VITALITY AND INNOVATION. The “Flemish Masters” project has THE FLEMISH MASTERS been established for the inquisitive PROJECT 2018-2020 traveller who enjoys learning about others as much as about him or The Flemish Masters project focuses Significant infrastructure herself. It is intended for those on the life and legacies of van Eyck, investments in tourism and culture who, like the Flemish Masters in Bruegel and Rubens active during are being made throughout their time, are looking to immerse th th th the 15 , 16 and 17 centuries, as well Flanders in order to deliver an themselves in new cultures and new as many other notable artists of the optimal visitor experience. In insights. time. addition, a programme of high- quality events and exhibitions From 2018 through to 2020, Many of the works by these original with international appeal will be VISITFLANDERS is hosting an Flemish Masters can be admired all organised throughout 2018, 2019 abundance of activities and events over the world but there is no doubt and 2020. -

With Jan Hoet

The history of exhibitions: beyond the white cube ideology (second part) Course on Contemporary Art and Culture MACBA, Autumn 2010 “““Chambres“Chambres d’amisd’amis”””” (1986) Jan Hoet November 15 ththth 2010, 19 h MACBA Auditorium “““Chambres“Chambres d’amisd’amis”””” Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent, but hosted in 58 pprivaterivate houses in Ghent 21th June ––– 21th September, 1986 Curator: Jan Hoet Artists: Carla Accardi, Christian Boltanski, Raf Buedts, Daniel Buren, Michael Buthe, Jacques Charlier, Nicola de Maria, Luciano Fabro, Günther Förg, Jef Geys, Dan Graham, Milan Grygar, François Hers, Kazuo Katase, Niek Kemps, Joseph Kosuth, Jannis Kounellis, Bertrand Lavier, Sol Lewitt, Danny Matthys, Gerhard Merz, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Helmut Middendorf, Juan Muñoz, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, Bruce Nauman, Maria Nordman, Oswald Oberhuber, Heike Pallanca, Panamarenko, Giulio Paolini, Royden Rabinowitch, Norbert Radermacher, Roger Raveel, Wolfgang Robbe, Claude Rutault, Reiner Ruthenbeck, Remo Salvadori, Rob Scholte, Ettore Spalletti, Paul Thek, Niele Toroni, Charles Vandenhove, Philip Van Isacker, Jan Vercruysse, Jean-Luc Vilmouth, Martin Walde, Lawrence Weiner, Robin Winters, Gilberto Zorio. A few statements on “Chambres d’amis” 1.1.1. “Intriguingly titled ‘Chambres d’Amis’ –-‘guest rooms’,” or, literally, ‘friends’ rooms’-– the show places art in 58 houses belonging to everyday townspeople, carrying the work outside the separate universe, the total institution, of the museum, to bring it within the private zone of the private home, an asocial place insofar as it is removed from the public arena. (...) His [Hoet’s] project takes the exhibition structure off its hinges, goes beyond the limits of the frame and spills over, whole, into an interior. -

Toezichtsrapport VRT - 2020

Inhoud Inleiding 1 Strategische doelstelling 1: Voor iedereen relevant 3 1.1. Voor alle doelgroepen 3 1.2. Aandacht voor diversiteit in beeldvorming 5 1.3. Aandacht voor diversiteit in toegankelijkheid 6 1.4. Aandacht voor diversiteit in personeelsbeleid 8 Strategische doelstelling 2: informatie, cultuur en educatie prioriteit 10 SD 2.1. Informatie | De VRT is de garantie op onpartijdige, onafhankelijke en betrouwbare informatie 10 en duiding SD 2.2. Cultuur | De VRT moedigt cultuurparticipatie aan, heeft aandacht voor de diverse culturele 19 uitingen in de Vlaamse samenleving en biedt een venster op de wereld 2.2.1. Cultuur voor alle Vlamingen 19 2.2.2. Aandacht voor diverse creatieve uitingen op een verbredende en verdiepende manier 20 2.2.3. Blijvende investeringen in lokale content 21 2.2.4. Cultuurparticipatie bevorderen 22 2.2.5. Een divers muziekbeleid dat kansen geeft aan jong, Vlaams talent 24 SD 2.3. Educatie | De VRT zal de Vlaamse mediagebruikers iets leren, hen inspireren en het actieve 27 burgerschap stimuleren 2.3.1. De VRT heeft een breed-educatieve rol 27 2.3.2. De VRT draagt bij tot de mediawijsheid van de Vlaamse mediagebruikers 29 2.3.3. De VRT zet meer in op documentaire 31 Strategische doelstelling 3: Publieke meerwaarde voor ontspanning en sport 33 SD 3.1. Ontspanning | Vlaams, verbindend en kwaliteitsvol 33 SD 3.2. Sport | Verbindend, universeel toegankelijk en participatie-bevorderend 34 Strategische doelstelling 4: Een aangescherpte merkenstrategie met VRT als kwaliteitslabel 37 4.1. Een duidelijk opgebouwde en dynamische merkenportfolio 37 4.2. Aangescherpte aanbodsmerken met focus op publieke meerwaarde 37 4.3. -

Luc Tuymans in the Dark Regions of The

Luc Tuymans In the Dark Regions of the My project is an effort to avert the critical gaze from the racial object to the racial World subject; from the described and the imagined to the describers and imaginers; from the serving to the served. - Toni Morrison" "Mwana Kitoko, The beautiful White Man." Thus did the people of the In Tuymans' oeuvre, a painting often acquires additional layers of Congo address their sovereign, Baudouin, king of the Belgians. Luc meaning through the precisely devised context of its first exhibition, Tuymans painted him descending the narrow stairs of his airplane in the frequently involving spaces that require a certain number and mid-fifties, wearing an immaculate white Navy uniform, looking just a combination of works. Even while painting, Tuymans often has a little too stiff for the elegance of his slim figure, one hand firmly precise notion of how the picture is to operate alone, together with grasping his sword, his eyes hidden behind sunglasses to protect them others, and in the room where it is first to be presented. In his most from the sun and the intrusive gaze of others. The painting of Baudouin, recent cycle for the David Zwirner Gallery in New York, the full- MWANA KITOKO (2000), shows a grand entrance in bright light that length portrait of the monarch is placed— among others—opposite a oscillates between the dazzling effect of a media event and the light of slightly smaller three-quarter portrait of a black man titled STATUE the tropics. The dark lens gives the figure an insect-like appearance. -

Tomma Abts Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël

Tomma Abts 2015 Books Zwirner David Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël Borremans Carol Bove R. Crumb Raoul De Keyser Philip-Lorca diCorcia Stan Douglas Marlene Dumas Marcel Dzama Dan Flavin Suzan Frecon Isa Genzken Donald Judd On Kawara Toba Khedoori Jeff Koons Yayoi Kusama Kerry James Marshall Gordon Matta-Clark John McCracken Oscar Murillo Alice Neel Jockum Nordström Chris Ofili Palermo Raymond Pettibon Neo Rauch Ad Reinhardt Jason Rhoades Michael Riedel Bridget Riley Thomas Ruff Fred Sandback Jan Schoonhoven Richard Serra Yutaka Sone Al Taylor Diana Thater Wolfgang Tillmans Luc Tuymans James Welling Doug Wheeler Christopher Williams Jordan Wolfson Lisa Yuskavage David Zwirner Books Recent and Forthcoming Publications No Problem: Cologne/New York – Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings – Yayoi Kusama: I Who Have Arrived In Heaven Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Ad Reinhardt Ad Reinhardt: How To Look: Art Comics Richard Serra: Early Work Richard Serra: Vertical and Horizontal Reversals Jason Rhoades: PeaRoeFoam John McCracken: Works from – Donald Judd Dan Flavin: Series and Progressions Fred Sandback: Decades On Kawara: Date Paintings in New York and Other Cities Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors – Who is sleeping on my pillow: Mamma Andersson and Jockum Nordström Kerry James Marshall: Look See Neo Rauch: At the Well Raymond Pettibon: Surfers – Raymond Pettibon: Here’s Your Irony Back, Political Works – Raymond Pettibon: To Wit Jordan Wolfson: California Jordan Wolfson: Ecce Homo / le Poseur Marlene -

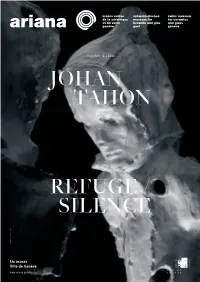

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

2019 ANNUAL REPORT 62Nd YEAR of ACTIVITY

PKB PRIVATBANK SA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 62nd YEAR OF ACTIVITY CONTENTS Governing bodies of PKB SA 4 Board of Directors’ Report 8 Highlights 9 Consolidated Financial Statements Comments on the consolidated balance sheet 12 Comments on the consolidated income statement 13 Consolidated balance sheet 14 Consolidated income statement 16 Consolidated cash flow statement 17 Statement of changes to shareholders' equity 18 Notes to the consolidated annual financial statements 19 Auditors' report 38 Parent Company Financial Statements Comments on the balance sheet 43 Comments on the income statement 45 Balance sheet 46 Income Statement 48 Appropriation of profits 49 Statement of changes to shareholders' equity 49 Notes to the annual financial statements 50 Auditors' report 61 GOVERNING BODIES OF PKB SA Board of Directors Edio Delcò 1) 3) 5) Taverne - Torricella (TI) Chairman Massimo Trabaldo Togna 1) 3) Milano (I) Vice-Chairman Umberto Trabaldo Togna 6) 7) Zug (ZG) Francesco Bellini Cavalletti 1) 4) Milano (I) Jean-Blaise Conne 2) 4) Lutry (VD) Giovanni Leonardi 2) 4) Bodio (TI) Pierre Poncet 3) 4) Vésenaz (GE) Giovanni Vergani 2) 4) Ruvigliana (TI) Secretary Federico Trabaldo Togna Conches (GE) Internal Audit Mirko Angelini Lead Auditor Diego Pecorone Internal Auditor Farah Vanoni Internal Auditor External Auditor Deloitte SA Executive Board Umberto Trabaldo Togna 8) Chief Executive Officer Luca Venturini 9) 10) Managing Director Ettore Bonsignore 11) Executive Vice President Michele Balice Executive Vice President Fabrizio Cerutti Executive Vice -

Luc Tuymans Good Luck

Luc Tuymans Good Luck October 27 – December 19, 2020 5–6/F, H Queen’s, 80 Queen’s Road Central Hong Kong Luc Tuymans, Still, 2019 © Luc Tuymans Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by the renowned Belgian artist Luc Tuymans (b. 1958) at the gallery’s Hong Kong location—his first solo presentation in Greater China. On view will be a selection of recent paintings and a new single-channel animated video that are drawn from a range of historical and contemporary images. Together the works share an undercurrent, as suggested by the exhibition’s title, of paradox and uncertainty. Tuymans has become known for a distinctive style of painting that demonstrates the power of images to simultaneously communicate and withhold. Emerging in the 1980s, Tuymans pioneered a decidedly non-narrative approach to figurative painting, instead exploring how information can be layered and embedded within certain scenes and signifiers. Based on preexisting imagery culled from a variety of sources, his works are rendered in a muted palette that is suggestive of a blurry recollection or a fading memory. Their quiet and restrained appearance, however, belies an underlying moral complexity, and they engage equally with questions of history and its representation as they do with quotidian subject matter. Tuymans’s canvases both undermine and reinvent traditional notions of monumentality through their insistence on the ambiguity of meaning. The present exhibition brings together a wide range of global, historical, and contemporary references that reflect ongoing themes of interest for the artist. -

Tony Oursler CV

Tony Oursler Lives and works in New York, NY, USA 1979 BFA, California Institute for the Arts, Valencia, CA, USA 1957 Born in New York, NY, USA Selected Solo Exhibitions 2021 ‘Tony Oursler: Black Box’, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan 2020 ‘Hypnose’, Musée d’arts de Nantes, Nantes, France Lisson Gallery, East Hampton, NY, USA 2019 ‘电流 (Current)’, Nanjing Eye Pedestrian Bridge, Nanjing, China ‘Tony Oursler: Water Memory’, Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, USA ‘The Volcano & Poetics Tattoo’, Dep Art Gallery, Milan, Italy 2018 ‘predictive empath’, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, USA ‘Tear of the Cloud’, Public Art Fund, Riverside Park South, New York, NY, USA ‘TC: the most interesting man alive’, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2017 ‘Paranormal: Tony Oursler vs. Gustavo Rol’, Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turin, Italy ‘Sound Digressions: Spectrum’, Galerie Mitterand, Paris, France ‘Tony Oursler: b0t / flOw - ch@rt’, Galerie Forsblom, Stockholm, Sweden ‘Tony Oursler: L7-L5 / Imponderable’, CaixaForum, Barcelona, Spain ‘Unidentified’, Redling Fine Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2016 ‘Tony Oursler: The Influence Machine’, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom ‘A*gR_3’, Galería Moisés Pérez De Albéniz, Madrid ‘M*r>0r’, Magasin III Museum & Foundation for Contemporary Art, Stockholm, Sweden ‘Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive’ Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY, USA ‘Imponderable’, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA ‘TC: The Most Interesting Man Alive’ Chrysler Museum, Norfolk,