Greening Documenta?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With Jan Hoet

The history of exhibitions: beyond the white cube ideology (second part) Course on Contemporary Art and Culture MACBA, Autumn 2010 “““Chambres“Chambres d’amisd’amis”””” (1986) Jan Hoet November 15 ththth 2010, 19 h MACBA Auditorium “““Chambres“Chambres d’amisd’amis”””” Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent, but hosted in 58 pprivaterivate houses in Ghent 21th June ––– 21th September, 1986 Curator: Jan Hoet Artists: Carla Accardi, Christian Boltanski, Raf Buedts, Daniel Buren, Michael Buthe, Jacques Charlier, Nicola de Maria, Luciano Fabro, Günther Förg, Jef Geys, Dan Graham, Milan Grygar, François Hers, Kazuo Katase, Niek Kemps, Joseph Kosuth, Jannis Kounellis, Bertrand Lavier, Sol Lewitt, Danny Matthys, Gerhard Merz, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Helmut Middendorf, Juan Muñoz, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, Bruce Nauman, Maria Nordman, Oswald Oberhuber, Heike Pallanca, Panamarenko, Giulio Paolini, Royden Rabinowitch, Norbert Radermacher, Roger Raveel, Wolfgang Robbe, Claude Rutault, Reiner Ruthenbeck, Remo Salvadori, Rob Scholte, Ettore Spalletti, Paul Thek, Niele Toroni, Charles Vandenhove, Philip Van Isacker, Jan Vercruysse, Jean-Luc Vilmouth, Martin Walde, Lawrence Weiner, Robin Winters, Gilberto Zorio. A few statements on “Chambres d’amis” 1.1.1. “Intriguingly titled ‘Chambres d’Amis’ –-‘guest rooms’,” or, literally, ‘friends’ rooms’-– the show places art in 58 houses belonging to everyday townspeople, carrying the work outside the separate universe, the total institution, of the museum, to bring it within the private zone of the private home, an asocial place insofar as it is removed from the public arena. (...) His [Hoet’s] project takes the exhibition structure off its hinges, goes beyond the limits of the frame and spills over, whole, into an interior. -

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

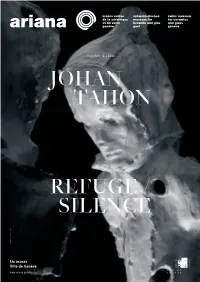

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

2019 ANNUAL REPORT 62Nd YEAR of ACTIVITY

PKB PRIVATBANK SA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 62nd YEAR OF ACTIVITY CONTENTS Governing bodies of PKB SA 4 Board of Directors’ Report 8 Highlights 9 Consolidated Financial Statements Comments on the consolidated balance sheet 12 Comments on the consolidated income statement 13 Consolidated balance sheet 14 Consolidated income statement 16 Consolidated cash flow statement 17 Statement of changes to shareholders' equity 18 Notes to the consolidated annual financial statements 19 Auditors' report 38 Parent Company Financial Statements Comments on the balance sheet 43 Comments on the income statement 45 Balance sheet 46 Income Statement 48 Appropriation of profits 49 Statement of changes to shareholders' equity 49 Notes to the annual financial statements 50 Auditors' report 61 GOVERNING BODIES OF PKB SA Board of Directors Edio Delcò 1) 3) 5) Taverne - Torricella (TI) Chairman Massimo Trabaldo Togna 1) 3) Milano (I) Vice-Chairman Umberto Trabaldo Togna 6) 7) Zug (ZG) Francesco Bellini Cavalletti 1) 4) Milano (I) Jean-Blaise Conne 2) 4) Lutry (VD) Giovanni Leonardi 2) 4) Bodio (TI) Pierre Poncet 3) 4) Vésenaz (GE) Giovanni Vergani 2) 4) Ruvigliana (TI) Secretary Federico Trabaldo Togna Conches (GE) Internal Audit Mirko Angelini Lead Auditor Diego Pecorone Internal Auditor Farah Vanoni Internal Auditor External Auditor Deloitte SA Executive Board Umberto Trabaldo Togna 8) Chief Executive Officer Luca Venturini 9) 10) Managing Director Ettore Bonsignore 11) Executive Vice President Michele Balice Executive Vice President Fabrizio Cerutti Executive Vice -

Tony Oursler CV

Tony Oursler Lives and works in New York, NY, USA 1979 BFA, California Institute for the Arts, Valencia, CA, USA 1957 Born in New York, NY, USA Selected Solo Exhibitions 2021 ‘Tony Oursler: Black Box’, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan 2020 ‘Hypnose’, Musée d’arts de Nantes, Nantes, France Lisson Gallery, East Hampton, NY, USA 2019 ‘电流 (Current)’, Nanjing Eye Pedestrian Bridge, Nanjing, China ‘Tony Oursler: Water Memory’, Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, USA ‘The Volcano & Poetics Tattoo’, Dep Art Gallery, Milan, Italy 2018 ‘predictive empath’, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, USA ‘Tear of the Cloud’, Public Art Fund, Riverside Park South, New York, NY, USA ‘TC: the most interesting man alive’, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2017 ‘Paranormal: Tony Oursler vs. Gustavo Rol’, Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turin, Italy ‘Sound Digressions: Spectrum’, Galerie Mitterand, Paris, France ‘Tony Oursler: b0t / flOw - ch@rt’, Galerie Forsblom, Stockholm, Sweden ‘Tony Oursler: L7-L5 / Imponderable’, CaixaForum, Barcelona, Spain ‘Unidentified’, Redling Fine Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2016 ‘Tony Oursler: The Influence Machine’, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom ‘A*gR_3’, Galería Moisés Pérez De Albéniz, Madrid ‘M*r>0r’, Magasin III Museum & Foundation for Contemporary Art, Stockholm, Sweden ‘Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive’ Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY, USA ‘Imponderable’, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA ‘TC: The Most Interesting Man Alive’ Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, -

Patrick Painter, Inc

PATRICK PAINTER, INC A. R. PENCK Born October 05, 1939 Currently lives and works in Ireland and Germany BIOGRAPHY 2004 Patrick Painter Inc., Santa Monica, Ca. 1999/2000 Exhibition of bronze sculptures in Heilbronn, Bremen, Recklinghausen, Luxembourg, Berlin and Bad Homburg. 1998 Extensive travelling exhibition throughout Japan. 1992 Takes part in documenta 9 in Kassel. 1989 Becomes Professor of Art at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. 1987 Receives the Nord/LB Prize for art. 1986 First Carrara marble sculptures appear. 1985 Awarded the artist’s prize by the city of Aachen. 1984/85 Various miniature sculptures in bronze. 1984 Participation in the 41st art festival in Venice together with Lothar Baumgarten. Increased interest in music. Joins work on the production of numerous Free Jazz Recordings. 1983 Extended visit to Israel. Settles in London and later in Ireland. 1982 Participation in documenta 7 in Kassel. Starts working with iron and bronze. First publication of the newspaper >Krater und Wolke< which is edited by A.R. Penck. 1980 On 3rd August travels to Lörsfeld/Kerpen (near Cologne) in the German Federal Republic. Awarded the Rembrandt Prize by the Goethe Foundation in Basel. Friendship with Markus Lüpertz and Per Kirkeby. Visits Joseph Beuys. 1979 Releases the first recording of >Gostritzer 92<. 1977 First wooden sculpture. Participation in documenta 6 in Kassel. First meeting with Jörg Immendorff in East Berlin. 1975 First major retrospective work at the Bern Kunsthalle. Awarded the Will Grohmann Prize by the Akademie der Künste in West Berlin. 1973/74 Spends six months working as a reserve for the People’s Army in the (former) German Democratic Republic. -

Télécharger La Biographie

Galerie Lelong & Co. Paris – New York A.R. Penck Expositions Exposition personnelle 2017 A. R. Penck - Strich = Welt, Kunsthalle Jesuitenkirche, Aschaffenbourg, Allemagne 2014 A.R. Penck - Expedition to the Holy Land - Portfolio mit 15 Graphiken und weitere Arbeiten auf Papier, KUNSTKABINETT, Ratisbonne , Allemagne 2013 A. R. Penck, Before the West: Select Works from the 1970s, Koenig & Clinton, New York, États-Unis 2012 Bilderwahl! - Encording Reality, Kunsthaus, Zurich, Suisse A. R. Penck, Hall Art Foundation, Reading, Royaume-Uni 2011 A. R. Penck: Vergangenheit-Gegenwart-Zukunft, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Allemagne A.R. Penck - Arbeiten auf Papier, Kunstverein Ulm, Ulm, Allemagne 2010 A.R. Penck: Grafik 1979-1998, Versicherungskammer Kulturstiftung - Kunstfoyer, Munich, Allemagne A. R. Penck, Kunsthalle Rostock, Rostock, Allemagne 2009 A. R. Penck - Druckgraphik, Lehr - Auktionshaus und Galerie, Berlin, Allemagne 2008 A.R. Penck - Retrospektive, Kunsthalle, Kiel, Allemagne A. R. Penck, Leeahn Gallery, Daegu, République de Corée A.R. Penck, de l'Est à l'Ouest, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France 2007 A.R. Penck - Arbeiten auf Papier, KUNSTKABINETT, Ratisbonne, Allemagne 13 rue de Téhéran, 75008 Paris – France / +33 1 45 63 13 19 / [email protected] / www.galerie-lelong.com 1 Galerie Lelong & Co. Paris – New York 2006 A.R. Penck, Koenig & Clinton, New York, États-Unis 2001 A. R. Penck - Frühe Bilder, Kunstsammlungen, Chemnitz, Allemagne 1999 A.R. Penk 1975 - 1998, Museum Villa Haiss, Zell am Harmersbach, Allemagne 1997 German Darkness and Contemporary Symbol, Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima, Japon 1996 A.R. Penck, Museo Tamayo, Mexico, Mexique 1995 A. R. -

Documenta.Pdf

Documenta Breastfeeding: Science and Society Working Group 11-13 May 1994 Documenta 28 Summary Report, pp. 35 Chemical hazards in developing countries Working Group, 21-23 October 1993 Documenta 27 Final Remarks, pp. 44 Man and his environment. Tropical forests and the conservation of species Study Week, 14-18 May 1990 Documenta 26 Conclusions, pp. 43 Science for development in a solidarity framework Study Week, 23-27 October 1989 Documenta 25 Conclusions, pp. 77 Agriculture and the quality of life. New global trends Study Week, 17-24 October 1988 Documenta 24 Conclusions, pp. 33 A modern approach to the protection of the environment Study Week, 2-7 November 1987 Documenta 23 pp. 24 Aspetti artistici della Casina Pio IV sede della Pontificia Accademia delle Scienze 28 Ottobre 1986 Carlo Pietrangeli Documenta 22 pp. 16 Historical aspects of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences 28 October 1986 G.B. Marini-Bettòlo Documenta 21 pp. 16 Allocution de Sa Sainteté Jean Paul II et discours de Carlos Chagas Président de l’Académie Audience Pontificale, 28 Octobre 1986 Documenta 20 (Texte français, anglais, italien), pp. 74 - 1 - Celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the restoration of the Academy (1936-1986) Inaugural address of President Carlos Chagas, 27 October 1986 Documenta 19 (English, French and Italian text), pp. 49 Molecular mechanisms of carcinogenic and antitumor activity Working group, 21-25 October 1986 Documenta 18 Conclusions, pp. 27 Persistent meteo-oceanographic anomalies and teleconnections Study Week, 23-27 September 1986 Documenta 17 Conclusions, pp. 21 Remote sensing and its impact on developing countries Study Week, 16-21 June 1986 Documenta 16 Conclusions, pp. -

Esposizioni Collettive (Selezione)

Esposizioni collettive (selezione) 1961 XII Premio Lissone internazionale per la pittura, Palazzo del Centro del Mobile, Lissone, dal 23 ottobre (catalogo) 1964 IX Premio Castello Svevo Termoli, Palazzo del Comune, Termoli, agosto (catalogo) 12 giorni La Salita grande vendita, Galleria La Salita, Roma, 19 dicembre 1964 - 5 gennaio 1965 1965 Accardi, Castellani, Paolini, Pistoletto, Twombly, Galleria Notizie, Torino, 28 maggio - 15 giugno (catalogo) 1966 Aspetti dell’avanguardia in Italia, Galleria Notizie, Torino, dal 4 ottobre (catalogo) Premio San Fedele 1966 per giovani pittori, Centro Culturale San Fedele, Milano, 10-29 ottobre (catalogo) Situazioni ’66, Galleria del Deposito, Genova, dal 20 dicembre 1967 Museo Sperimentale d’Arte Contemporanea, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Torino, dal 26 aprile (catalogo) Tendenze oggi in Italia, Galleria d’arte moderna Il Chiodo, Palermo, 1-20 maggio (catalogo) Confronti, Galleria Christian Stein, Torino, giugno - luglio Arte Povera - Imspazio, Galleria La Bertesca, Genova, dal 4 ottobre (catalogo) Collage 1, Università di Genova, Istituto di Storia dell’Arte, Genova, 13-21 dicembre 1968 Arte Povera, Galleria de' Foscherari, Bologna, 24 febbraio - 15 marzo (catalogo) Arte Povera, Centro Arte Viva - Feltrinelli, Trieste, 23 marzo - 11 aprile (pieghevole) Il percorso, Studio Arco d’Alibert, Roma, 23 marzo - 16 aprile Fabro, Kounellis, Paolini, Qui arte contemporanea, Roma, dal 24 aprile (catalogo) Teatro delle mostre, Galleria La Tartaruga, Roma, 6-31 maggio (catalogo) 6. Premio Nazionale di Pittura Masaccio, San Giovanni Valdarno (Arezzo), 23 giugno - 24 luglio (catalogo) Arte povera più azioni povere, Arsenali dell’Antica Repubblica, Amalfi, 4-6 ottobre (catalogo) Revort 2, VI Settimana Internazionale di Palermo, Palermo, 27-31 dicembre www.fondazionepaolini.it [email protected] 1969 Premier Festival International de la Peinture, Château-Musée, Cagnes-sur-mer, 29 marzo - 7 aprile (catalogo) Otto + otto + otto. -

Christopher Williams Born 1956 in Los Angeles

This document was updated March 3, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Christopher Williams Born 1956 in Los Angeles. Lives and works in Cologne, Chicago, and Los Angeles. EDUCATION & TEACHING 2008 - present Professor, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf 1981 M.F.A., California Institute of the Arts, Valencia 1978 B.F.A., California Institute of the Arts, Valencia SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Christopher Williams: Footwear (Adapted for Use), David Zwirner, New York 2019 Christopher Williams - MODEL: Kochgeschirre, Kinder, Viet Nam (Angepasst zum Benutzen), C/O Berlin 2018 Christopher Williams: Normative Models, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover [catalogue] 2017 Christopher Williams: Books Plus, ARCHIV, Zurich Christopher Williams: Models, Open Letters, Prototypes, Supplements, La Triennale di Milano, Milan Chirstopher Williams: Open Letter: The Family Drama Refunctioned? (From the Point of View of Production), David Zwirner, London Christopher Williams. Stage Play. Supplements, Models, Prototypes, Miller’s, Zurich [organized by gta exhibitions, ETH Zurich] Christopher Williams: Supplements, Models, Prototypes, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago Christopher Williams: Supplements, Models, Prototypes, ETH Zurich, Institute gta, Zurich 2016 Christopher Williams, Capitain Petzel, Berlin 2014 Christopher Williams. For Example: Dix-Huit Leçons Sur La Société Industrielle (Revision 19), David Zwirner, New York [artist publication] Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, Art Institute of Chicago [itinerary: The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitechapel Gallery, London] [catalogue] Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, Galerie Mezzanin, Vienna Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, Musée d’art moderne et contemporain (MAMCO), Geneva [part of Des histoires sans fin/Endless stories series] 2013 Christopher Williams, Volker Bradtke, Düsseldorf Christopher Williams. -

HAIM STEINBACH Education Solo Exhibitions

HAIM STEINBACH 1944 Born in Rehovot, Israel Works in Queens, New York Education 1973 MFA Yale University 1968 BFA Pratt Institute 1966 Diploma Université d'Aix-Marseille Solo exhibitions 2019 appear to use, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Los Angeles 2018 every single day, Museum Kurhaus, Kleve, Germany; Museion, Bolzano, Italy, 2019 zerubabbel, Magasin III Museum and Foundation for Contemporary Art, Jaffa, Tel Aviv mojave, Hubert Winter Gallery, Vienna 2017 jaws, White Cube, London lemon yellow, Lia Rumma, Naples, Italy 2016 omaobamaoldsmobile, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York 2015 ADAA Art Show, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Park Avenue Armory, New York 2014 Fresh: Haim Steinbach and Objects From the Permanent Collection, The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas 2013 The Window, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen Travel, White Cube, London Once Again the World is Flat, CCS Bard, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York; Serpentine Gallery, London, 2014; Kunsthalle Zurich, 2014 collections, Lia Rumma, Milan, Italy 2012 Navy Legacy, Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris The Artist's Institute, New York 2011 creature, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York 2010 PLS5/2SB, Louis Vuitton Maison, London 2009 Pets, Galerie Almine Rech, Paris Paris Meets Berlin Project, Haim Steinbach and Taryn Simon, Johann Koenig Gallery, Berlin 2008 The Effect, Waddington Custot, London Special Project: Mr. Peanut /Haim Steinbach on Mike Kelley, Overduin and Kite, Los Angeles 2007 Galerie Laurent Godin, Paris Lia Rumma, Milan, Italy Sonnabend Gallery, New York Vistamare, Pescara, Italy Akira Ikeda -

2.3 Curating Biennales

2 Curating 61 2.3 Curating Biennales This section will examine the emergence of the professional profile of the biennale curator as they exist today. The goal will be to highlight several seminal moments in its development, in order to show the challenges and debates that define it. The focus in this section is on Documenta in Kassel, because it has been a site for many important developments in biennale curating, but also because it illustrates how many different factors—geopolitics, art history, global vs local—are brought to- gether and negotiated through curatorial practice. The section will focus on three particularly important editions of documenta, each significant for its own reasons. The first section will examine the inaugural Documenta in 1955, and thedebates around Harald Szeemann’s Documenta in 1972, and the second section will exam- ine Enwezor’s Documenta 11 in 2002. Each will focus on different parts of what make up biennale curatorship, though of course it being the same festival, there are certain threads that flow through all of the editions. 2.3.1 DocumentaV Documenta was originally established in 1955 by professor and exhibition-designer Arnold Bode. The exhibition was put on with the intention of repudiating the Nazi- era branding of modernism as degenerate art (Entartete Kunst), and reintegrating Germany with avant-garde artistic movements, in an attempt to modernize and move forward after the trauma of war. Bode’s inspiration came from his visit to the Venice Biennale of 1954, demonstrating the importance of Venice as a site for the dissemination of the biennale model (Wallace 2011, 5). -

Guide to the Colin De Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection Processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel

CCS Bard Archives Phone: 845.758.7567 Center for Curatorial Studies Fax: 845.758.2442 Bard College Email: [email protected] Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504 Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel. This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on February 06, 2019 . Describing Archives: A Content Standard Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Scope and Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Arrangement .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Administrative Information ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings ....................................................................................................................................