2.3 Curating Biennales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

With Jan Hoet

The history of exhibitions: beyond the white cube ideology (second part) Course on Contemporary Art and Culture MACBA, Autumn 2010 “““Chambres“Chambres d’amisd’amis”””” (1986) Jan Hoet November 15 ththth 2010, 19 h MACBA Auditorium “““Chambres“Chambres d’amisd’amis”””” Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent, but hosted in 58 pprivaterivate houses in Ghent 21th June ––– 21th September, 1986 Curator: Jan Hoet Artists: Carla Accardi, Christian Boltanski, Raf Buedts, Daniel Buren, Michael Buthe, Jacques Charlier, Nicola de Maria, Luciano Fabro, Günther Förg, Jef Geys, Dan Graham, Milan Grygar, François Hers, Kazuo Katase, Niek Kemps, Joseph Kosuth, Jannis Kounellis, Bertrand Lavier, Sol Lewitt, Danny Matthys, Gerhard Merz, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Helmut Middendorf, Juan Muñoz, Hidetoshi Nagasawa, Bruce Nauman, Maria Nordman, Oswald Oberhuber, Heike Pallanca, Panamarenko, Giulio Paolini, Royden Rabinowitch, Norbert Radermacher, Roger Raveel, Wolfgang Robbe, Claude Rutault, Reiner Ruthenbeck, Remo Salvadori, Rob Scholte, Ettore Spalletti, Paul Thek, Niele Toroni, Charles Vandenhove, Philip Van Isacker, Jan Vercruysse, Jean-Luc Vilmouth, Martin Walde, Lawrence Weiner, Robin Winters, Gilberto Zorio. A few statements on “Chambres d’amis” 1.1.1. “Intriguingly titled ‘Chambres d’Amis’ –-‘guest rooms’,” or, literally, ‘friends’ rooms’-– the show places art in 58 houses belonging to everyday townspeople, carrying the work outside the separate universe, the total institution, of the museum, to bring it within the private zone of the private home, an asocial place insofar as it is removed from the public arena. (...) His [Hoet’s] project takes the exhibition structure off its hinges, goes beyond the limits of the frame and spills over, whole, into an interior. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Ingeborg Lüscher Biography

Ingeborg Lüscher Biography 1936 Born as Ingeborg Löffler in Freiberg in Saxony (Germany) 1946 – 1949 Rudolf-Steiner-School in Dresden 1 1949 Relocation to West Berlin 1956 School-leaving examinations 1956 – 1958 Acting studies at drama school Marlise Ludwig, Berlin, state-approved graduation 1958 First film engagements, including the main female role of Madelon in “Cardillac”, the first b/w Ufa TV film after the end of World War II (story E. T. A. Hoffmann) Ensemble member at Vagantenbühne and Renaissance Theater Berlin, tour to Switzerland 1959 Meets the Swiss colour psychologist Max Lüscher, marriage Ensemble member at Komödie Basel, main female role of Dynamene in the Swiss TV film “Ein Phönix zuviel / A Phenix Too Frequent” with original dialogues by Christopher Fry 2 1960 – 1967 Psychological studies, including at the Berlin Free University Numerous main female roles in b/w TV films, like “Jennifer” 1965, Alwine von Valencay in Jean Anouilh‘s „Leben wie die Fürsten” 1966 (directed by Helmut Käutner) and Laura Manulescu in „Des Rätsels Lösung“ 1966 (with Ivan Desny) 1967 Journey to India Relocation to Ticino (Switzerland) Film shootings in Prague, Gräfin Nettelburg in the TV film „Till Eulenspiegel“ (with Helmut Lohner) Meets dissidents of the later Prague Spring and starts critical questioning the own role in her life Separation from Max Lüscher Turns to fine art as an autodidact and takes the former studio of Hans Arp in Locarno 1967 - 1972 Works with fire and with cigarette stubs Contact to artists of the Nouveau Réalisme www.ingeborgluescher.com 1969 Travels to New York, meets Tiny Duchamp, Christo and Andy Warhol Discovers the hermit Armand Schulthess at Onsernone Valley (Switzerland), starts the photographic documentation of his encyclopedic forest („Der größte Vogel kann nicht fliegen. -

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

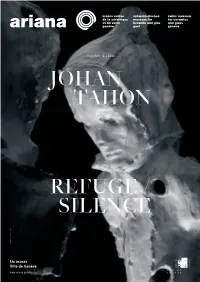

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

2019 ANNUAL REPORT 62Nd YEAR of ACTIVITY

PKB PRIVATBANK SA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 62nd YEAR OF ACTIVITY CONTENTS Governing bodies of PKB SA 4 Board of Directors’ Report 8 Highlights 9 Consolidated Financial Statements Comments on the consolidated balance sheet 12 Comments on the consolidated income statement 13 Consolidated balance sheet 14 Consolidated income statement 16 Consolidated cash flow statement 17 Statement of changes to shareholders' equity 18 Notes to the consolidated annual financial statements 19 Auditors' report 38 Parent Company Financial Statements Comments on the balance sheet 43 Comments on the income statement 45 Balance sheet 46 Income Statement 48 Appropriation of profits 49 Statement of changes to shareholders' equity 49 Notes to the annual financial statements 50 Auditors' report 61 GOVERNING BODIES OF PKB SA Board of Directors Edio Delcò 1) 3) 5) Taverne - Torricella (TI) Chairman Massimo Trabaldo Togna 1) 3) Milano (I) Vice-Chairman Umberto Trabaldo Togna 6) 7) Zug (ZG) Francesco Bellini Cavalletti 1) 4) Milano (I) Jean-Blaise Conne 2) 4) Lutry (VD) Giovanni Leonardi 2) 4) Bodio (TI) Pierre Poncet 3) 4) Vésenaz (GE) Giovanni Vergani 2) 4) Ruvigliana (TI) Secretary Federico Trabaldo Togna Conches (GE) Internal Audit Mirko Angelini Lead Auditor Diego Pecorone Internal Auditor Farah Vanoni Internal Auditor External Auditor Deloitte SA Executive Board Umberto Trabaldo Togna 8) Chief Executive Officer Luca Venturini 9) 10) Managing Director Ettore Bonsignore 11) Executive Vice President Michele Balice Executive Vice President Fabrizio Cerutti Executive Vice -

04/2014 Heldart Saadane Afif William Copley S.M.S., William Copley S.M.S

04/2014 Heldart Saadane Afif William Copley S.M.S., William Copley S.M.S. In 2013 Heldart buys an edition named Shit Must Stop (S.M.S.). In a random conversation with artist Saadane Afif it becomes apparent that Afif is very familiar with the S.M.S. edition that was put together by the legendary William Copley, in 1968. The Marcel Duchamp prize winner Afif acquires a complete copy of the edition as well. Heldart plans exhibiting the S.M.S. edition and invites Saadane Afif to react to that endeavor. In order to participate Afif in turn recquires Heldart to assemble a selection from the 72 works contained in the S.M.S. edition and to position itself with that selection. He then in turn refers to the selection, says Afif. Heldart follows through despite its opinion that curating in general is an academic discipline and reserved to institutional activities such as museums and other scientifically relevant art contexts. In any event the result can be seen at the newly opened shopping mall called Binkini Berlin hosted in the former Bikinihaus. Saadane Afifs’ commentary consists of doubling Heldart's selection. The choice to show in a shopping mall is no coincidence. The work is not for sale and an apparent yet entirely different affirmation to the original idea behind the Shit Must Stop edition by Copley. The idea Copley’s in 1968 was to neutralize the commercial power of galleries and the political-institutional arrogance of museums by sending the self-produced edition containing the best contemporary artists of its time to art collectors directly by mail. -

Tony Oursler CV

Tony Oursler Lives and works in New York, NY, USA 1979 BFA, California Institute for the Arts, Valencia, CA, USA 1957 Born in New York, NY, USA Selected Solo Exhibitions 2021 ‘Tony Oursler: Black Box’, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan 2020 ‘Hypnose’, Musée d’arts de Nantes, Nantes, France Lisson Gallery, East Hampton, NY, USA 2019 ‘电流 (Current)’, Nanjing Eye Pedestrian Bridge, Nanjing, China ‘Tony Oursler: Water Memory’, Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, USA ‘The Volcano & Poetics Tattoo’, Dep Art Gallery, Milan, Italy 2018 ‘predictive empath’, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, CO, USA ‘Tear of the Cloud’, Public Art Fund, Riverside Park South, New York, NY, USA ‘TC: the most interesting man alive’, Lisson Gallery, New York, NY, USA 2017 ‘Paranormal: Tony Oursler vs. Gustavo Rol’, Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turin, Italy ‘Sound Digressions: Spectrum’, Galerie Mitterand, Paris, France ‘Tony Oursler: b0t / flOw - ch@rt’, Galerie Forsblom, Stockholm, Sweden ‘Tony Oursler: L7-L5 / Imponderable’, CaixaForum, Barcelona, Spain ‘Unidentified’, Redling Fine Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2016 ‘Tony Oursler: The Influence Machine’, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom ‘A*gR_3’, Galería Moisés Pérez De Albéniz, Madrid ‘M*r>0r’, Magasin III Museum & Foundation for Contemporary Art, Stockholm, Sweden ‘Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive’ Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY, USA ‘Imponderable’, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA ‘TC: The Most Interesting Man Alive’ Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, -

Download Full Biography

Sadie Coles HQ William Nelson Copley (CPLY) Biography 1919 born in New York City (NY), educated at Phillips Academy and Yale University 1942-46 Military service in Africa and Italy 1947-48 directs Copley Galleries in Beverly Hills (CA),USA, (with John Ployardt) 1947 begins to paint 1951 moves to Paris 1963 returns to New York (NY) 1992 moves to Key West, Florida where he lives until his death 1996 dies in Key West, Florida Selected Solo Exhibitions 2018 The Coffin They Carry You Off In, ICA Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, Miami (FL), USA Candice Breitz: Sex work. In dialogue with works by William N. Copley from The Frieder Burda Collection, Museum Frieder Burda | Salon Berlin, Berlin 2017 Women, Paul Kasmin Gallery, 515 W. 27th Street, New York 2016 Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy The World According to CPLY, The Menil Collection, Houston (TX) 2015 Drawings (1962 – 1973), Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York (NY) 2013 Confiserie CPLY, Marktplatz 19, Basel, Switzerland 2012 The Patriotism of CPLY and All That, Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York (NY) Frieda Burder Museum, Baden Baden, Germany Reflection a Past Life, Linn Lühn, Düsseldorf, Germany 2011 X-Rated, Sadie Coles HQ, London 2010 me Collectors Room, Berlin X-Rated, Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York (NY) 2009 Galerie Klaus Gerrit Friese, Stuttgart, Germany Western songs, El Sourdog Hex, Berlin Linn Lühn, Cologne, Germany 2007 Linn Lühn, Cologne, Germany 2006 Works from the 1970’s, Nolan/Eckman Gallery, New York (NY) Galerie manus presse/Klaus Gerrit Friese, Stuttgart, Germany 2005 Galerie Onrust, -

Documenta 5 Working Checklist

HARALD SZEEMANN: DOCUMENTA 5 Traveling Exhibition Checklist Please note: This is a working checklist. Dates, titles, media, and dimensions may change. Artwork ICI No. 1 Art & Language Alternate Map for Documenta (Based on Citation A) / Documenta Memorandum (Indexing), 1972 Two-sided poster produced by Art & Language in conjunction with Documenta 5; offset-printed; black-and- white 28.5 x 20 in. (72.5 x 60 cm) Poster credited to Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Ian Burn, Michael Baldwin, Charles Harrison, Harold Hurrrell, Joseph Kosuth, and Mel Ramsden. ICI No. 2 Joseph Beuys aus / from Saltoarte (aka: How the Dictatorship of the Parties Can Overcome), 1975 1 bag and 3 printed elements; The bag was first issued in used by Beuys in several actions and distributed by Beuys at Documenta 5. The bag was reprinted in Spanish by CAYC, Buenos Aires, in a smaller format and distrbuted illegally. Orginally published by Galerie art intermedai, Köln, in 1971, this copy is from the French edition published by POUR. Contains one double sheet with photos from the action "Coyote," "one sheet with photos from the action "Titus / Iphigenia," and one sheet reprinting "Piece 17." 16 ! x 11 " in. (41.5 x 29 cm) ICI No. 3 Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Poster 33 x 23 " in. (84.3 x 60 cm) ICI /Documenta 5 Checklist page 1 of 13 ICI No. 4 Lawrence Weiner A Primer, 1972 Artists' book, letterpress, black-and-white 5 # x 4 in. (14.6 x 10.5 cm) Documenta Catalogue & Guide ICI No. 5 Harald Szeemann, Arnold Bode, Karlheinz Braun, Bazon Brock, Peter Iden, Alexander Kluge, Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Exhibition catalogue, offset-printed, black-and-white & color, featuring a screenprinted cover designed by Edward Ruscha. -

Patrick Painter, Inc

PATRICK PAINTER, INC A. R. PENCK Born October 05, 1939 Currently lives and works in Ireland and Germany BIOGRAPHY 2004 Patrick Painter Inc., Santa Monica, Ca. 1999/2000 Exhibition of bronze sculptures in Heilbronn, Bremen, Recklinghausen, Luxembourg, Berlin and Bad Homburg. 1998 Extensive travelling exhibition throughout Japan. 1992 Takes part in documenta 9 in Kassel. 1989 Becomes Professor of Art at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. 1987 Receives the Nord/LB Prize for art. 1986 First Carrara marble sculptures appear. 1985 Awarded the artist’s prize by the city of Aachen. 1984/85 Various miniature sculptures in bronze. 1984 Participation in the 41st art festival in Venice together with Lothar Baumgarten. Increased interest in music. Joins work on the production of numerous Free Jazz Recordings. 1983 Extended visit to Israel. Settles in London and later in Ireland. 1982 Participation in documenta 7 in Kassel. Starts working with iron and bronze. First publication of the newspaper >Krater und Wolke< which is edited by A.R. Penck. 1980 On 3rd August travels to Lörsfeld/Kerpen (near Cologne) in the German Federal Republic. Awarded the Rembrandt Prize by the Goethe Foundation in Basel. Friendship with Markus Lüpertz and Per Kirkeby. Visits Joseph Beuys. 1979 Releases the first recording of >Gostritzer 92<. 1977 First wooden sculpture. Participation in documenta 6 in Kassel. First meeting with Jörg Immendorff in East Berlin. 1975 First major retrospective work at the Bern Kunsthalle. Awarded the Will Grohmann Prize by the Akademie der Künste in West Berlin. 1973/74 Spends six months working as a reserve for the People’s Army in the (former) German Democratic Republic. -

Clarissa Ricci Towards a Contemporary Venice Biennale: Reassessing the Impact of the 1993 Exhibition

Journal On Biennials Why Venice? Vol. I, No. 1 (2020) and Other Exhibitions Clarissa Ricci Towards a Contemporary Venice Biennale: Reassessing the Impact of the 1993 Exhibition Abstract This paper argues that Cardinal Points of Art, directed by Achille Bonito Oliva has been decisive in the formation of the contemporary Venice Biennale. The 45th Venice Biennale, (1993) was memorable for many reasons: the first exhibi- tion of Chinese painters in Venice, its transnational approach, and because it was the last time the Aperto exhibition was shown. Nevertheless, this was a complex and much criticised Biennale whose specific characteristics are also connected to the process of reform that the institution had been undergoing since the 1970s. The analysis of the exhibition starts with the examination of this legacy and continues by questioning Bonito Oliva’s curatorial contribution in order to define the specific features which helped to shape the contemporary Venice Biennale. Keywords Venice Biennale, Aperto, 1993, Achille Bonito Oliva, Nomadism, Coexistence, Contemporaneity OBOE Published online: September 16, 2020 Journal On Biennials and Other Exhibitions To cite this article: Clarissa Ricci, “Towards a Contemporary Venice Biennale: Reassessing the Impact of the 1993 Exhibition”, OBOE Journal I, no. 1 (2020): ISSN 2724-086X 78-98. oboejournal.com To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.25432/2724-086X/1.1.0007 Journal On Biennials Why Venice? Vol. I, No. 1 (2020) and Other Exhibitions Towards a Contemporary Venice Biennale: Reassessing the Impact of the 1993 Exhibition¹ Clarissa Ricci Introduction The format of today’s Venice Biennale is the result of a long intellectual and polit- ical negotiation.