[I Shall Grieve for You Forever]: Early Nova Scotian Gaelic Laments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the HIGHLAND COUNCIL the Proposal Is to Establish a Catchment Area for Bun-Sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar, and a Gaelic Medium

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL The proposal is to establish a catchment area for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar, and a Gaelic Medium catchment area for Lochaber High School EDUCATIONAL BENEFITS STATEMENT THIS IS A PROPOSAL PAPER PREPARED IN TERMS OF THE EDUCATION AUTHORITY’S AGREED PROCEDURE TO MEET THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOLS (CONSULTATION) (SCOTLAND) ACT 2010 INTRODUCTION The Highland Council is proposing, subject to the outcome of the statutory consultation process: • To establish a catchment area for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar. The new Gàidhlig Medium (GM) catchment will overlay the current catchments of Banavie Primary School, Caol Primary School, Inverlochy Primary School, Lundavra Primary School, Roy Bridge Primary School, Spean Bridge Primary School, and St. Bride’s Primary School • To formalise the current arrangements relating to Gàidhlig Medium Education (GME) in related secondary schools, under which the catchment area for Lochaber High School will apply to both Gàidhlig Medium and English Medium education, and under which pupils from the St. Bride’s PS catchment (part of the Kinlochleven Associated School Group) have the right to attend Lochaber High School to access GME, provided they have previously attended Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar. • Existing primary school catchments for the provision of English Medium education will be unaffected. • The proposed changes, if approved, will be implemented at the conclusion of the statutory consultation process. If implemented as drafted, the proposed catchment for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar will include all of the primary school catchments within the Lochaber ASG, except for that of Invergarry Primary School. The distances and travel times to Fort William from locations within the Invergarry catchment make it unlikely that GM provision would be attractive to parents of primary school age children, and dedicated transport from the Invergarry catchment could result in excessive cost being incurred. -

£795,000 (Freehold) Sound of Arisaig, Inverness Shire, PH38 4NG

Offers Over Glenuig Inn £795,000 (Freehold) Sound Of Arisaig, Inverness Shire, PH38 4NG Multi award winning Superb public areas Operating on a year-round Picturesque trading Includes spacious Highland Inn set in a and stunning business basis, trading profitably Outstanding external location offering 6 and separate 1- stunning coastal location on benefiting from providing a “home and income” al-fresco trading generously sized and well- bedroom owners’ the Sound of Arisaig and on numerous accolades for lifestyle opportunity, the areas plus ample appointed en-suite letting apartment plus the north/south route from its green credentials business has undoubted private parking for bedrooms plus a modern excellent 3-bedroom Mull to Skye, not far from and a VisitScotland 3- potential for new owners to guests 9-bed bunkhouse staff flat the Road to the Isles Star rating expand trade further INTRODUCTION Glenuig Inn is a charming property with many unique features and situated in a stunning trading location in an area of outstanding natural beauty. This alluring part of the West Highlands of Scotland has a unique character and is steeped in history. It is thought that the Inn, being recorded as being built pre-1745, was the site of an old drover’s Inn. The original subjects are of stone construction and the present owners have developed the property so that it has retained much of its original character whilst expressing the quality and comfort demanded by modern day guests and visitors. Glenuig Inn’s waterside location overlooking the Sound of Arisaig with Loch Nan Uamh to the north and views of the Small Isles of Rum, Eigg and Muck and Skye on the horizon, makes it popular with the many visitors to the region and the business is a ‘destination location’ for Lochaber residents, tourists from further afield and those working in the area. -

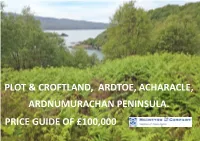

Price Guide of £100,000 Plot & Croftland, Ardtoe

PLOT & CROFTLAND, ARDTOE, ACHARACLE, ARDNUMURACHAN PENINSULA. PRICE GUIDE OF £100,000 LOCATION: McIntyre & Company, Tranquil location on the Ardnamurchan Peninsula Ardtoe is located close to the glorious Kentra Bay, and the main 38 High Street, Fort William, Set amongst stunning mountain scenery village of Acharacle. There are lots of historic sites, beaches and PH33 6AT Enjoying views over Kentra Bay castles nearby as well as it being accessible to the Isles Mull. Tel: 01397 703231 Plot extending to approx 0.261 hectare Ardtoe is primarily serviced by Acharacle a semi-rural village Croftland included extends to approx 0.6707 hectare Fax: 01397 705070 which is very well equipped with amenities to include a large, Planning in Principal for 1½ story dwelling E-mail: [email protected] well-stocked and licensed grocery shop, bakery with café Website: www.solicitors-scotland.com attached, garage, internet coffee shop, a hotel and restaurants. Acharacle has an established and vibrant community, many of These particulars are not guaranteed and are not to be incorporated into any formal missives of sale/ SERVICES: purchase to follow hereon. The measurements and conversions are approximations only and are not be founded upon. Offers should be submitted to the Selling Agents in Scottish Legal Terms. The Seller will whom support and engage in various activities at the local not be bound to accept the highest, or indeed any offer. Interested parties should register their interest The plot is situated off the B8044 and enjoys an idyllic and with the Selling Agents lest a closing date for offers is set, but the Seller will not be obliged to proceed to Community Hall to include regular church luncheons, coffee a closing date. -

Mull and Iona

Public transport guide to Mull and Iona © Copyright Jonathan Wilkins (see page 2) © Copyright Tom Richardson (see page 2) © Copyright Stuart Wilding (see page 2) from 30 March until 20 October 2012 ISSUE 5 Welcome to Travel times Index This handbook is one of a series of comprehensive guides to Destination Service No. Pages Public Transport to, from and within the Argyll and Bute area. Ardlui (Àird Laoigh) Rail 16,17 Arle (Airle) 495 8,9 It provides all the latest information about bus, train, ferry and Aros Bridge (Drochaid Àrais) 495 8,9 coach times and routes giving you the opportunity to see the Arrochar and Tarbet (An t-Àrar Rail 16,17 options available for work, shopping and leisure travel. or An Tairbeart ) Bunessan (Bun Easain) 496 12,13 Calgary (Calgairidh) 494 12,13 Whom to contact… Campbeltown (Ceann Loch 926 14, 15 Chille Chiarain) Buses and Coaches Connel (A’ Choingheal) Rail 16,17 Anderson Coaches 01546 870354 Craignure (Creag an Iubhair) 495, 496, Ferry, 6-9,12,13, Awe Service Station 01866 822612 Creagan Park (Pàirc a’ 494 12,13 Bowmans Coaches 01680 812313 Chreagain) First Glasgow 0141 4236600 Crianlarich (A’ Chrìon-Làraich) Rail 16,17 Garelochhead Minibuses and Coaches Ltd 01436 810050 Dalmally (Dail Mhàilidh) Rail 16,17 Islay Coaches 01496 840273 Dervaig (Dearbhaig) 494 12,13 Charles MacLean 01496 820314 Drimnin (Na Druiminnean) 507 18,19 D.A. and A.J. Maclean 01496 220342 Dunoon (Dùn Omhain) 486 14, 15 McColl's Coaches 01389 754321 Edinburgh (Dùn Èideann) Rail 16,17 McGills Bus Service Ltd. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Population Change in Lochaber 2001 to 2011

The Highland Council Agenda 5 Item Lochaber Area Committee Report LA/2/14 No 27 February 2014 Population Change in Lochaber 2001 To 2011 Report by Director of Planning and Development Summary This report presents early results from the 2011 Census, giving local information on the number and ages of people living within Lochaber. It compares these figures with those from 2001 to show that the population has “aged”, and that there is a large number of people who are close to retirement age. The population of Lochaber has grown by 6.1% (compared to the Highland average of 11.1%) with an increase in both Wards, and at a local level in 18 out of 27 data zones. Local population growth is strongly linked to the building of new homes. 1. Background 1.1. Publication of the results from the 2011 Census began in December 2012, and the most recent published in November and December 2013 gave the first detailed results for “census output areas”, the smallest areas for which results are published. These detailed results have enabled preparation of the first 2011 Census profiles and these are available for Wards, Associated School Groups, Community Councils and Settlement Zones on the Highland Council’s website at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/yourcouncil/highlandfactsandfigures/census2011.htm 1.2. This report returns to some earlier results and looks at how the age profile of the Lochaber population and the total numbers have changed at a local level (datazones). The changes for Highland are summarised in Briefing Note 57 which is attached at Appendix 1. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Eadar Canaan Is Garrabost (Between Canaan and Garrabost): Religion in Derick Thomson's Lewis Poetry

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 46 Issue 1 Article 14 8-2020 Eadar Canaan is Garrabost (Between Canaan and Garrabost): Religion in Derick Thomson’s Lewis Poetry Petra Johana Poncarová Charles University, Prague Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, and the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons Recommended Citation Poncarová, Petra Johana (2020) "Eadar Canaan is Garrabost (Between Canaan and Garrabost): Religion in Derick Thomson’s Lewis Poetry," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 46: Iss. 1, 130–142. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol46/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EADAR CANAAN IS GARRABOST (BETWEEN CANAAN AND GARRABOST): RELIGION IN DERICK THOMSON’S LEWIS POETRY Petra Johana Poncarová Since the Scottish Reformation of the sixteenth-century, the Protestant, Calvinist forms of Christianity have affected Scottish life and have become, in some attitudes, one of the “marks of Scottishness,” a “means of interpreting cultural and social realities in Scotland.”1 However treacherous and limiting such an assertion of Calvinism as an essential component of Scottish national character may be, the experience with radical Presbyterian Christianity has undoubtedly been one of the important features of life in the -

The Isle of Lewis & Harris (Chaps. VII & VIII)

THE ISLE OF LEWIS AND HARRIS CHAPTER I A STUDY IN ENVIRONMENT AND LANDSCAPE BRITISH COMMUNITY (A) THE GEOGRAPHIC SETTING: THE BRITISH ISLES, SCOTLAND AND THE by HIGHLANDS AND ISLES ARTHUR GEDDES i. A 'Heart' of the 'North and West' of Britain The Isle of Lewis and Harris (1955) by Arthur Geddes, the son N the ' Outer' Hebrides, commonly regarded as the of the great planner and pioneering human ecologist Patrick Geddes, is long out of print from EUP and hard to procure. most ' outlying ' inhabited lands of the British Isles, Chapters VII and VIII on the spiritual and religious life of the I are revealed not only the most ancient of British rocks, community remain of very great importance, and this PDF of the Archaean, but probably the oldest form of communal them has been produced for my students' use and not for any life in Britain. This life, in present and past, will interest commercial purpose. Also, below is Geddes' remarkable map of the Hebrides from p. 3, and at the back the contents pages. Alastair Mclntosh, Honorary Fellow, University of Edinburgh. EDINBURGH AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS *955 FIG. I.—Global view of the ' Outer' Hebrides, seen as the heart of the ' North and West' of Britain. 3 CH. VII SPIRITUAL LIFE OF COMMUNITY xviii. 19-20). The worldly wise might think that the spiritual fare of these poor folk must have been lean indeed ; while others, having heard much of the Highlanders' ' pagan ' superstitions, may think even worse ! The evi CHAPTER VII dence from which to judge is found in survivals from a rich lore, and for most readers seen but ' darkly' through THE SPIRITUAL LIFE OF THE prose translations from the poetry of a tongue now known COMMUNITY to few. -

Eadar Croit Is Kiosk: Bàrdachd an Fhicheadamh Linn | University of Glasgow

09/25/21 Eadar Croit is Kiosk: Bàrdachd an fhicheadamh linn | University of Glasgow Eadar Croit is Kiosk: Bàrdachd an View Online fhicheadamh linn @article{Mac A’ Ghobhainn_1983, place={Glaschu}, title={‘An Dotair Leòinte: Bàrdachd Dhòmhnaill MhicAmhlaigh (Ath-sgrùdadh)’}, volume={125}, journal={Gairm}, publisher={[s.n.]}, author={Mac A’ Ghobhainn, I.}, year={1983}, pages={68–73} } @book{Mac A’ Ghobhainn_2014, place={Inbhir Nis}, title={Bannaimh nach gann: a’ bhàrdachd aig An t-Urramach Murchadh Mac a' Ghobhainn, 1878-1936}, publisher={Clò Fuigheagan}, author={Mac A’ Ghobhainn, Murchadh}, editor={Smith, Maggie}, year={2014} } @book{Bennett_Rice_Bennett_Bennett_MacCallum_MacCallum_MacCallum_2014, place={Ochtertyre}, title={Eilean Uaine Thiriodh: beatha, òrain agus ceòl Ethel NicChaluim = The green isle of Tiree : the life, songs and music of Ethel MacCallum}, publisher={Grace Note Publications}, author={Bennett, Margaret and Rice, Eric and Bennett, Margaret and Bennett, Margaret and MacCallum, Ethel and MacCallum, Ethel and MacCallum, Ethel}, year={2014} } @book{Black_1999a, place={Edinburgh}, title={An tuil: anthology of 20th century Scottish Gaelic verse}, publisher={Polygon}, author={Black, Ronald}, year={1999} } @book{Black_1999b, place={Edinburgh}, title={An tuil: anthology of 20th century Scottish Gaelic verse}, publisher={Polygon}, author={Black, Ronald}, year={1999} } @book{Brown_Dawson Books_2007a, place={Edinburgh}, title={The Edinburgh history of Scottish literature: Volume 3: Modern transformations: new identities (from 1918)}, -

Macdonald Bards from Mediaeval Times

O^ ^^l /^^ : MACDONALD BARDS MEDIEVAL TIMES. KEITH NORMAN MACDONALD, M.D. {REPRINTED FROM THE "OBAN TIMES."] EDINBURGH NORMAN MACLEOD, 25 GEORGE IV. BRIDGE. 1900. PRBPACB. \y^HILE my Papers on the " MacDonald Bards" were appearing in the "Oban Times," numerous correspondents expressed a wish to the author that they would be some day presented to the pubUc in book form. Feeling certain that many outside the great Clan Donald may take an interest in these biographical sketches, they are now collected and placed in a permanent form, suitable for reference ; and, brief as they are, they may be found of some service, containing as they do information not easily procurable elsewhere, especially to those who take a warm interest in the language and literature of the Highlands of Scotland. K. N. MACDONALD. 21 Clarendon Crescknt, EDINBURGH, October 2Uh, 1900. INDEX. Page. Alexander MacDonald, Bohuntin, ^ ... .. ... 13 Alexander MacAonghuis (son of Angus), ... ... ... 17 Alexander MacMhaighstir Alasdair, ... ... ... ... 25 Alexander MacDonald, Nova Scotia, ... .. .. ... 69 Alexander MacDonald, Ridge, Nova Scotia, ... ... .. 99 Alasdair Buidhe MacDonald, ... .. ... ... ... 102 Alice MacDonald (MacDonell), ... ... .. ... ... 82 Alister MacDonald, Inverness, ... ... .. ... ... 73 Alexander MacDonald, An Dall Mòr, ... ... ... .. 43 Allan MacDonald, Lochaber, ... ... ... ... .. 55 Allan MacDonald, Ridge, Nova Scotia, ... .... ... ... 101 Am Bard Mucanach (Tlie Muck Bard), ... ... .. ... 20 Am Bard CONANACH (The Strathconan Bard), .. ... ... 48 An Aigeannach, -

Beard2016.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ROB DONN MACKAY: FINDING THE MUSIC IN THE SONGS Ellen L. Beard Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2015 ABSTRACT AND LAY SUMMARY This thesis explores the musical world and the song compositions of eighteenth-century Sutherland Gaelic bard Rob Donn MacKay (1714-1778). The principal focus is musical rather than literary, aimed at developing an analytical model to reconstruct how a non-literate Gaelic song-maker chose and composed the music for his songs. In that regard, the thesis breaks new ground in at least two ways: as the first full-length study of the musical work of Rob Donn, and as the first full-length musical study of any eighteenth-century Scottish Gaelic poet. Among other things, it demonstrates that a critical assessment of Rob Donn merely as a “poet” seriously underestimates his achievement in combining words and music to create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.