The Epic of Pabuji Ki Par in Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Pushkar Lake

Available online a twww.scholarsresearchlibrary.com Scholars Research Library Archives of Applied Science Research, 2016, 8 (6):1-7 (http://scholarsresearchlibrary.com/archive.html) ISSN 0975-508X CODEN (USA) AASRC9 Effect of anthropogenic activities on Indian pilgrimage sites–A case study of Pushkar Lake Deepanjali Lal 1 and Joy Joseph Gardner 2 School of Life Sciences, Jaipur National University, Jagatpura, Jaipur, Rajasthan Department of Geography, University of Rajasthan, JLN Marg, Jaipur, Rajasthan _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Water is the source of life for all living beings. About two-thirds of the Earth is covered by water. Among many water bodies, Lakes are the most fertile, diversified and productive of all the ecosystems in the world. A variety of environmental goods and services are bestowed upon us by Lakes which makes them vulnerable to human exploitation. The fresh water Pushkar Lake is situated in the gap of the Aravallis and was used as the area of research for the present study. History claims that in the 20 th century, this Lake and its catchment area were a rich source of wildlife as well as a source of water for the railways for over 70 years, till 2004. The society’s demand for economic gains has resulted in the deterioration of its water quality. Two main reasons for this loss are – high rate of sedimentation due to sand-fall from the nearby sand dunes and anthropogenic practices followed in the periphery of the Lake. The water of the Lake is getting dried up because of reversal of hydraulic gradient from Lake to groundwater, leading to rapid decline in the groundwater level of the surrounding areas also. -

Survey of Fresh Water Bodies of Ajmer

Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 SURVEY OF FRESH WATER BODIES OF AJMER Dr Rashmi Sharma , Ashok Sharma , Amogh Bhardwaj and Devesh Bhardwaj Associate Professor SPCGCA MDSU AJMER [email protected] Abstract Ajmer is situated in the center of Rajasthan , also known as heart of Rajasthan . Rajasthan is the western arid state of INDIA. Ajmer is situated 25 0 38 ‘ -26 0 56 ‘ north latitude and 73 0 54 - 75 0 22 ‘ East longitude. Area of Ajmer is 8481 sq km. Population of Ajmer is 5.43 lakhs. Ajmer has semiarid Eastern plane and Arid western plane. Semiarid and arid zones are devided by Aravallis , which are oldest mountains of the world. Ajmer comes in Agroclimate IIIA zone. Ajmer has 9 tehsils and 8 Panchayat Samitis. Total 1130 villages are there in Ajmer. Ajmer has 4 fresh water lakes , Anasagar , Foysagar and Pushkar and one more small Budha Pushkar. Ajmer gets its drinking water from Bisalpur dam which is situated in Tonk district. Introduction The fresh water bodies of Ajmer are Anasagar , Foy sagar , Pushkar and Budha Pushkar : Anasagar is feigned lake situated in center of Ajmer . It was made by King Arnoraja ( He was Grand father of King Prithviraj Chouhan ). The lake spreads 13 km. Baradari (Pavilion ) was build by Shahjaha (1637) and the Garden Daulat Bagh by King Volume IX, Issue VI, JUNE/2020 Page No : 7604 Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 Jehangir . Circuit house was British Residency. The catchment area 1.9 sq mi (5 km ), the depth of lake is 4.5 m the storage capacity of lake is 4750000 m 3. -

Management of Lakes in India M.S.Reddy1 and N.V.V.Char2

10 March 2004 Management of Lakes in India M.S.Reddy1 and N.V.V.Char2 1. Introduction There is no specific definition for Lakes in India. The word “Lake” is used loosely to describe many types of water bodies – natural, manmade and ephemeral including wetlands. Many of them are euphemistically called Lakes more by convention and a desire to be grandiose rather than by application of an accepted definition. Vice versa, many lakes are categorized as wetlands while reporting under Ramsar Convention. India abounds in water bodies, a preponderance of them manmade, typical of the tropics. The manmade (artificial) water bodies are generally called Reservoirs, Ponds and Tanks though it is not unusual for some of them to be referred to as lakes. Ponds and tanks are small in size compared to lakes and reservoirs. While it is difficult to date the natural lakes, most of the manmade water bodies like Ponds and Tanks are historical. The large reservoirs are all of recent origin. All of them, without exception, have suffered environmental degradation. Only the degree of degradation differs. The degradation itself is a result of lack of public awareness and governmental indifference. The situation is changing but slowly. Environmental activism and legal interventions have put sustainability of lakes in the vanguard of environmental issues. This paper is an attempt at presenting a comprehensive view of the typical problems experienced in the better known lakes, their present environmental status and efforts being made to make them environmentally sustainable. 1.1 Data India is well known for the huge variance in its lakes, but the data is nebulous. -

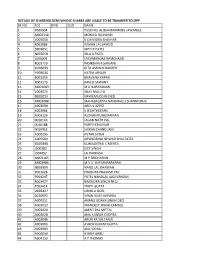

List of Candidates Recommended to the Post of LDC in PCDA (NC), Jammu

List of Candidates Recommended to the post of LDC in PCDA (NC), Jammu:- S.No NAME OF THE CATEGORY ROLL No. RANK NOMINATION CANDIDATE STATUS 01 PRIYANKA JINDAL UR 2201007537 1495 Nominated 02 JAI PARKASH UR 2201521044 1566 Nominated 03 ATUL KUMAR UR 2201521419 1601 Nominated 04 KAVITA TRIPATHI UR 3003020032 1637 Incomplete Documents 05 NIRAJ UPADHYAY UR 3003030214 1659 Nominated 06 SUSHANT KUMAT UR 3206020341 1687 Nominated 07 VIKASH KUMAR UR 3206075846 1708 Nominated 08 DEEPAK KUMAR UR 3206123542 1719 Incomplete Documents 09 VIJAY KUMAR OBC 3205006857 2291 Nominated 10 SHASHI BHUSHAN OBC 3206123545 2333 Incomplete KUMAR Documents 11 DHANANJAY KUMAR OBC 3010030643 2362 Incomplete Documents 12 KRISHNA PRASAD OBC 3206007914 2377 Nominated 13 PARTAP SINGH OBC-OH 2201017521 2681 Nominated 14 GANGADHARAN P UR-ExS. 7204700901 2980 Incomplete Documents The dossiers of the above said candidates have been forwarded to following address and the Candidates may enquire for further process from the Concerned office:- Shri Sardari Lal, Dy C.D.A. (AN), O/o The Pr. Cont. of Defence Accounts (NC), Narwal Pain,Satwari, JAMMU (J&K). The Candidates with Incomplete Documents are given a final chance to submit their documents till 21.06.2011 at SSC, NWR Chandigarh otherwise their candidature will be cancelled. List of Candidates Recommended to the post of LDC in M/o External Affairs for their office located in J&K:- NAME OF THE NOMINATION S.No CATEGORY ROLL No. RANK CANDIDATE STATUS 01 KOMAL MITHAL UR 2201620226 1427 Nominated Nominated 02 AKASH GUPTA UR 2201506389 -

Details of Shareholders Whose Shares Are Liable to Be Transfer to Iepf Sr.No Fol Dpid Clid Name 1 Y000004 Yusufali Alibhaikarimj

DETAILS OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE SHARES ARE LIABLE TO BE TRANSFER TO IEPF SR.NO FOL DPID CLID NAME 1 Y000004 YUSUFALI ALIBHAIKARIMJEE JAWANJEE 2 M003118 MONICA DILAWARI 3 V003054 V CHANDRA SHEKHAR 4 K003086 KISHAN LAL JANGID 5 D003051 DIPTI P PATEL 6 N003058 NILA A PATEL 7 L003009 LACHMANDAS RAMCHAND 8 R003170 RASIKBHAI K SAVJANI 9 G003039 GITA ASHWIN BANKER 10 H003036 HATIM ARIAAR 11 B003056 BHAVANA KAPASI 12 R003173 RAVI D SAWANT 13 M003083 M A NARAYANAN 14 V003075 VIJAY MALLYA 15 N003055 NAYEEMUDDIN SYED 16 M003088 MAHABALAPPA NANDIHALLI SHANMUKHA 17 A003090 ABDUL AZEEZ 18 K003066 K JEGATHEESAN 19 A003126 ASOKAN KUNJURAMAN 20 0010146 JAGAN NATH PAL 21 0010188 PARTH KHAKHAR 22 0010953 SHIKAR CHAND JAIN 23 A000295 AVTAR SINGH 24 A005583 ARVINDBHAI ISHWAR BHAI PATEL 25 G003898 GUNVANTRAI C MEHTA 26 J000382 JEET SINGH 27 J004092 JAI PARKASH 28 M003185 M P SRIDHARAN 29 M003986 M.V.S. SURYANARAYANA 30 N003999 NAND LAL DHAWAN 31 P003628 PRADNYA PRAKASH PAI 32 P004247 PATEL NANDLAL JAGJIVANDAS 33 R003427 RAJENDRA SINGH NEGI 34 T003414 TRIPTI GUPTA 35 U003427 URMILA GOEL 36 0010970 KIRAN VIJAY JAIPURIA 37 A000311 ANANG UDAYA SINGH DEO 38 A003013 AMARJEET SINGH KAMBOJ 39 A003020 AMRIT PAL MITTAL 40 A003028 ANIL KUMAR CHOPRA 41 A003046 ARUN KR SULTANIA 42 A003066 ASHOK KUMAR GUPTA 43 A003983 ANIL GOYAL 44 A004030 A RAJA BABU 45 A004113 A T THOMAS 46 A004564 A. RAJA BABU 47 A004666 ANIL KUMAR LUKKAD 48 A004677 ASHA DEVI 49 A004915 ASHOK GUPTA 50 A005458 ANURAG JAIN 51 A005468 AGA REDDY VANTERU 52 B000031 BHAIRULAL GULABCHAND 53 B000049 BALMUKAND AGARWAL -

Download Trip Description

WILD PHOTOGRAPHY H O L ID AY S MAGICAL RAJASTHAN & THE PUSHKAR CAMEL FAIR A COLOURFUL & LUXURIOUS JOURNEY THROUGH ICONIC INDIA HIGHLIGHTS “…wanted to say a huge thank you to Martin & Geraldine researched locations in between. Arguably the men of • The Pushkar Camel Fair for organising such an outstanding trip to Rajasthan, it Rajasthan wear the biggest turbans in India and the wo- • Jodhpur’s ‘Blue City’ was all we had hoped for and more. The hotels were out men the most beautifully coloured Saris. This photo- • Jaipur’s ‘Pink City’ of this world very traditional and classy. All of the photo graphic tour has been designed carefully to minimise the • Eagles of Mehrangarh Fort locations were spot on, we both learned so much and the long journeys that are often common in this vast state. • Superb street photography memories will last a lifetime.” David & Miri, Rajasthan We will travel executive class by train to Jaipur on Day 2 • Historic palaces, forts and temples and take a fight from Udaipur back to Delhi on day 14. • Flower Markets and Bazaars INTRODUCTION One of the highlights of our photographic journey is the • Udaipur romantic ‘Venice’ of India Rajasthan, “Land of Great Kings” was the frst state to signifcant and celebrated Pushkar Camel Fair, one of the • Aravelli Hills and Rankapur fully embrace tourism in India. This is refected in the continent’s last great traditional melas. This is a spec- • Classic train journey sophistication of the state’s infra-structure for tourists. tacle on a truly epic scale and is the largest of its kind in Our hotels is Rajasthan are all delightful quiet havens the world. -

Carleton College Alumni Adventure with Religion Professor Roger Jackson October 14–November 5, 2009

Carleton College Alumni Adventure With Religion Professor Roger Jackson October 14–November 5, 2009 Day 01: Wednesday, 14 October: Departure from U.S. Day 02: Thursday, 15 October: Enroute Day 03: Friday, 16 October: Arrive Delhi early a.m. Transfer to Hotel Taj Ambassador (or similar). Visit Connaught Place, National Museum, Humayun’s tomb, Qutub Minar, and a Hindu temple for evening arati. Connaught Place – At the hub of the British-built city of New Delhi, India’s capital, Connaught Place is a lively center for commerce, hotels, restaurants, and culture. National Museum, New Delhi – This museum holds over 200,000 works of art, both of Indian and foreign origin covering more than 5,000 years of cultural heritage. It includes collections of archaeology, jewelry, paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, manuscripts, Central Asian antiquities, arms and armor, etc.. Humayun's Tomb (UNESCO World Heritage Site; see below) – Humayun, the second Mughal emperor, is buried in this tomb, the first great example of Mughal garden tomb architecture and a model for the Taj Mahal. It was built in 1565 by the Persian architect Miraq Mirza Ghiyas. Qutab Minar (UNESCO World Heritage Site) – The Qutab Minar towers over the historic area where Qutabuddin Aibak laid the foundation of Delhi Sultanate in 1193. He built the Quwatul Islam Mosque and 1 the Qutab Minar to announce the advent of the Muslim sultans. Later Iltutmish, Alauddin Khilji and Ferozshah Tuglak added new buildings and new architectural styles. Evening: Visit a Hindu Temple and witness the basic ritual of arti. Overnight – Hotel Taj Ambassador. Day 04: Saturday, 17 October: Delhi Visit Red Fort, Jama Masjid, Jain Temple, Rajghat Red Fort (UNESCO World Heritage Site) – Red sandstone battlements give this imperial citadel the name Red Fort (Lal Quila). -

Elizabeth Wickett

Oral Tradition, 27/2 (2012): 333-350 Patronage, Commodification, and the Dissemination of Performance Art: The Shared Benefits of Web Archiving Elizabeth Wickett Introduction This essay addresses the aesthetic and ethical dimensions of documenting oral performance on film, the evolution of a polymodal form of archival documentation leading to online monographs, and the question of how performers may benefit from the archival process— specifically with reference to performances of the epic of Pabuji in Rajasthan, India.1 Owing to digital technology and the emergence of the Internet as a broadcasting forum and marketing agent, a phenomenon has occurred which we might term the “commodification” of expressive culture. In this technological universe where sounds and images are sold for the benefit of some (but not others), issues of copyright, intellectual property rights, and the commercialization and marketing of expressive culture on the web have become paramount.2 Video excerpts are being broadcast around the world in free and open formats.3 Whereas documentation of oral performance traditions by scholars and for scholars was once the norm, I propose that we—as ethnographers, linguists, and folklorists—must ensure that such performers can also benefit from the process of academic study and documentation, with support for the perpetuation of their livelihood as well as their cultural and artistic legacy. How do we as scholars and ethnographic filmmakers respond to these challenges and use these media to the performers’ benefit? 1 I am very grateful to the Firebird Foundation for Anthropological Research for their funding of the filming and archival documentation of four performances of the oral epic of Pabuji ki par across Rajasthan in 2008 and its production as five films in 2009 (Wickett 2009). -

Conservation and Management of Lakes – an Indian Perspective Conservation and Management of Lakes –An Indian Perspective

First published 2010 © Copyright 2010, Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, New Delhi Material from this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part only for educational purpose with due acknowledgement of the source. Text by: Brij Gopal, Ex-Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi M. Sengupta, Former Adviser, Ministry of Environment and Forests, New Delhi R. Dalwani, Director, Ministry of Environment and Forests, New Delhi S.K. Srivastava, Dy Director, Ministry of Environment and Forests, New Delhi Satellite images of lakes reproduced from GoogleEarth®. 2 Conservation and Management of Lakes – An Indian Perspective Conservation and Management of Lakes –An Indian Perspective National River Conservation Directorate Ministry of Environment and Forests (MOEF) Government of India New Delhi 110003 Lake Fatehsagar, Udaipur ii Conservation and Management of Lakes – An Indian Perspective t;jke jes'k jkT; ea=kh (Lora=k izHkkj) JAIRAM RAMESH i;kZoj.k ,oa ou Hkkjr ljdkj ubZ fnYyh& 110003 MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI -110 003 28th July 2010 Message It gives me great pleasure to introduce to you all this publication on the conservation and management of India’s lakes and wetlands, as a follow-up of the 12th World Lake Conference. This publication will surely serve to be useful reference material for policymakers, implementing agencies, environmentalists and of course those of us who enjoy the diversity and beauty of India’s water bodies. The importance of this publication also stems from how valuable our lakes and wetlands are to our ecosystems. They are not only a source of water and livelihood for many of our populations, but they also support a large proportion of our biodiversity. -

Shikohabad Dealers Of

Dealers of Shikohabad Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09104200008 SK0000058 HARENDRA SINGH CONTR. SHIKOHABAD 2 09104200013 SK0002065 PENGORIA GENERAL STORE KATRA BAZAR SKD. 3 09104200027 SK0002509 KHANDELWAL TRADING CORP. SIRSAGANJ 4 09104200032 SK0005780 NANAK NIRANKARI AGRI.INSTRUMENTS SIRSAGANJ 5 09104200046 SK0000578 SUBHASH MEDICAL & FANCY STORE SHIKOABAD 6 09104200051 SK0003696 NARESH CHANDRA AGRAWAL SIRSAGANJ SHIKOHABAD 7 09104200065 SK0003751 NEW PUNJAB CYCLE STORE SHIKOHABAD 8 09104200070 SK0001115 ASHOK & SONS BADA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 9 09104200079 SK0004336 SHIV KUMAR GRAIN DEALER SHIKOHABAD 10 09104200084 SK0004045 SHOKARI RAM KHATTRI DIESEL SHIKOHABAD 11 09104200098 SK0003423 OM MEDICAL STORE SHIKOHA BAD 12 09104200107 SK0003990 LALLA BOOK DEPO. KATRA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 13 09104200112 SK0000486 JAY MA.STEEL FURNITURE SERSAGANJ SHIKOHABAD 14 09104200126 SK0005876 AMIT SOAP WORKS SIRSAGANJ SHIKOHABAD 15 09104200131 SK0006151 DEEP MEDICAL HALL SEKOHABAD 16 09104200145 SK0006708 KISHORE EMPORIUM SHIKOHABAD 17 09104200150 SK0006810 SHYAM TIMBER MART SHIKOHABAD 18 09104200159 SK0008042 R.K.CHEMICAL KATRA MEERA SIKOHABAD 19 09104200164 SK0008661 DIMOND HOSIERY SHIKOHABAD 20 09104200178 SK0006895 SRI DURGA OIL IND. ETAH ROAD SHIKOHABAD 21 09104200183 SK0009804 AGARWAL BOOK DEPOT KATRA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 22 09104200197 SK0010062 AGRAWAL PATTAL BHANDAR 37 FOOLS PURIA SKD. 23 09104200206 SK0010199 RAJ PAL TRADERS PANJABI COLONY SHIKOHABAD 24 09104200211 SK0011986 NATIONAL ENGG. WORKS STATION ROAD SHIKOHABAD 25 09104200225 SK0011097 HEERA LAL BACHHI LAL SIRSA GANJ SHIKOHABAD 26 09104200230 SK0011432 SRI AMBEDKAR SIRSA GANJ SHIKOHABAD GRAMODHYOGSEWASANSTHAN 27 09104200239 SK0011518 KRISHNA BOARD MILL MISRANA SKD. 28 09104200244 SK0011508 GAURI SHANKAR PREM NARAYIN BADA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 29 09104200258 SK0012220 JAIN PACKING INDUSTRIES 635 MISRANA SHIKOHABAD 30 09104200263 SK0012219 PALIWAL GLASS WORKS FIROZABAD ROAD SHIKOHABAD 31 09104200277 SK0002926 PRAKASH MEDICAL STORE SIRSA GANJ SKD. -

Ancient Civilizations

1 Chapter – 1 Ancient Civilizations Introduction - The study of ancient history is very interesting. Through it we know how the origin and evolution of human civilization, which the cultures prevailed in different times, how different empires rose uplifted and declined how the social and economic system developed and what were their characteristics what was the nature and effect of religion, what literary, scientific and artistic achievements occrued and thease elements influenced human civilization. Since the initial presence of the human community, many civilizations have developed and declined in the world till date. The history of these civilizations is a history of humanity in a way, so the study of these ancient developed civilizations for an advanced social life. Objective - After teaching this lesson you will be able to: Get information about the ancient civilizations of the world. Know the causes of development along the bank of rivers of ancient civilizations. Describe the features of social and political life in ancient civilizations. Mention the achievements of the religious and cultural life of ancient civilizations. Know the reasons for the decline of various civilizations. Meaning of civilization The resources and art skills from which man fulfills all the necessities of his life, are called civilization. I.e. the various activities of the human being that provide opportunities for sustenance and safe living. The word 'civilization' literally means the rules of those discipline or discipline of those human behaviors which lead to collective life in human society. So civilization may be called a social discipline by which man fulfills all his human needs. -

Annual-Report-2014-2015-Ministry-Of-Information-And-Broadcasting-Of-India.Pdf

Annual Report 2014-15 ANNUAL PB REPORT An Overview 1 Published by the Publications Division Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India Printed at Niyogi offset Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi 20 ANNUAL 2 REPORT An Overview 3 Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Annual Report 2014-15 ANNUAL 2 REPORT An Overview 3 45th International Film Festival of India 2014 ANNUAL 4 REPORT An Overview 5 Contents Page No. Highlights of the Year 07 1 An Overview 15 2 Role and Functions of the Ministry 19 3 New Initiatives 23 4 Activities under Information Sector 27 5 Activities under Broadcasting Sector 85 6 Activities under Films Sector 207 7 International Co-operation 255 8 Reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and other Backward Classes 259 9 Representation of Physically Disabled Persons in Service 263 10 Use of Hindi as Official Language 267 11 Women Welfare Activities 269 12 Vigilance Related Matters 271 13 Citizens’ Charter & Grievance Redressal Mechanism 273 14 Right to Information Act, 2005 Related Matters 277 15 Accounting & Internal Audit 281 16 CAG Paras (Received From 01.01.2014 To 31.02.2015) 285 17 Implementation of the Judgements/Orders of CATs 287 18 Plan Outlay 289 19 Media Unit-wise Budget 301 20 Organizational Chart of Ministry of I&B 307 21 Results-Framework Document (RFD) for Ministry of Information and Broadcasting 315 2013-2014 ANNUAL 4 REPORT An Overview 5 ANNUAL 6 REPORT Highlights of the Year 7 Highlights of the Year INFORMATION WING advertisements. Consistent efforts are being made to ● In order to facilitate Ministries/Departments in promote and propagate Swachh Bharat Mission through registering their presence on Social media by utilizing Public and Private Broadcasters extensively.