Elizabeth Wickett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Candidates Recommended to the Post of LDC in PCDA (NC), Jammu

List of Candidates Recommended to the post of LDC in PCDA (NC), Jammu:- S.No NAME OF THE CATEGORY ROLL No. RANK NOMINATION CANDIDATE STATUS 01 PRIYANKA JINDAL UR 2201007537 1495 Nominated 02 JAI PARKASH UR 2201521044 1566 Nominated 03 ATUL KUMAR UR 2201521419 1601 Nominated 04 KAVITA TRIPATHI UR 3003020032 1637 Incomplete Documents 05 NIRAJ UPADHYAY UR 3003030214 1659 Nominated 06 SUSHANT KUMAT UR 3206020341 1687 Nominated 07 VIKASH KUMAR UR 3206075846 1708 Nominated 08 DEEPAK KUMAR UR 3206123542 1719 Incomplete Documents 09 VIJAY KUMAR OBC 3205006857 2291 Nominated 10 SHASHI BHUSHAN OBC 3206123545 2333 Incomplete KUMAR Documents 11 DHANANJAY KUMAR OBC 3010030643 2362 Incomplete Documents 12 KRISHNA PRASAD OBC 3206007914 2377 Nominated 13 PARTAP SINGH OBC-OH 2201017521 2681 Nominated 14 GANGADHARAN P UR-ExS. 7204700901 2980 Incomplete Documents The dossiers of the above said candidates have been forwarded to following address and the Candidates may enquire for further process from the Concerned office:- Shri Sardari Lal, Dy C.D.A. (AN), O/o The Pr. Cont. of Defence Accounts (NC), Narwal Pain,Satwari, JAMMU (J&K). The Candidates with Incomplete Documents are given a final chance to submit their documents till 21.06.2011 at SSC, NWR Chandigarh otherwise their candidature will be cancelled. List of Candidates Recommended to the post of LDC in M/o External Affairs for their office located in J&K:- NAME OF THE NOMINATION S.No CATEGORY ROLL No. RANK CANDIDATE STATUS 01 KOMAL MITHAL UR 2201620226 1427 Nominated Nominated 02 AKASH GUPTA UR 2201506389 -

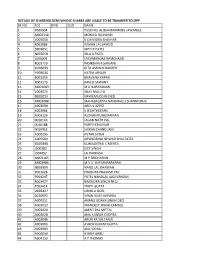

Details of Shareholders Whose Shares Are Liable to Be Transfer to Iepf Sr.No Fol Dpid Clid Name 1 Y000004 Yusufali Alibhaikarimj

DETAILS OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE SHARES ARE LIABLE TO BE TRANSFER TO IEPF SR.NO FOL DPID CLID NAME 1 Y000004 YUSUFALI ALIBHAIKARIMJEE JAWANJEE 2 M003118 MONICA DILAWARI 3 V003054 V CHANDRA SHEKHAR 4 K003086 KISHAN LAL JANGID 5 D003051 DIPTI P PATEL 6 N003058 NILA A PATEL 7 L003009 LACHMANDAS RAMCHAND 8 R003170 RASIKBHAI K SAVJANI 9 G003039 GITA ASHWIN BANKER 10 H003036 HATIM ARIAAR 11 B003056 BHAVANA KAPASI 12 R003173 RAVI D SAWANT 13 M003083 M A NARAYANAN 14 V003075 VIJAY MALLYA 15 N003055 NAYEEMUDDIN SYED 16 M003088 MAHABALAPPA NANDIHALLI SHANMUKHA 17 A003090 ABDUL AZEEZ 18 K003066 K JEGATHEESAN 19 A003126 ASOKAN KUNJURAMAN 20 0010146 JAGAN NATH PAL 21 0010188 PARTH KHAKHAR 22 0010953 SHIKAR CHAND JAIN 23 A000295 AVTAR SINGH 24 A005583 ARVINDBHAI ISHWAR BHAI PATEL 25 G003898 GUNVANTRAI C MEHTA 26 J000382 JEET SINGH 27 J004092 JAI PARKASH 28 M003185 M P SRIDHARAN 29 M003986 M.V.S. SURYANARAYANA 30 N003999 NAND LAL DHAWAN 31 P003628 PRADNYA PRAKASH PAI 32 P004247 PATEL NANDLAL JAGJIVANDAS 33 R003427 RAJENDRA SINGH NEGI 34 T003414 TRIPTI GUPTA 35 U003427 URMILA GOEL 36 0010970 KIRAN VIJAY JAIPURIA 37 A000311 ANANG UDAYA SINGH DEO 38 A003013 AMARJEET SINGH KAMBOJ 39 A003020 AMRIT PAL MITTAL 40 A003028 ANIL KUMAR CHOPRA 41 A003046 ARUN KR SULTANIA 42 A003066 ASHOK KUMAR GUPTA 43 A003983 ANIL GOYAL 44 A004030 A RAJA BABU 45 A004113 A T THOMAS 46 A004564 A. RAJA BABU 47 A004666 ANIL KUMAR LUKKAD 48 A004677 ASHA DEVI 49 A004915 ASHOK GUPTA 50 A005458 ANURAG JAIN 51 A005468 AGA REDDY VANTERU 52 B000031 BHAIRULAL GULABCHAND 53 B000049 BALMUKAND AGARWAL -

Shikohabad Dealers Of

Dealers of Shikohabad Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09104200008 SK0000058 HARENDRA SINGH CONTR. SHIKOHABAD 2 09104200013 SK0002065 PENGORIA GENERAL STORE KATRA BAZAR SKD. 3 09104200027 SK0002509 KHANDELWAL TRADING CORP. SIRSAGANJ 4 09104200032 SK0005780 NANAK NIRANKARI AGRI.INSTRUMENTS SIRSAGANJ 5 09104200046 SK0000578 SUBHASH MEDICAL & FANCY STORE SHIKOABAD 6 09104200051 SK0003696 NARESH CHANDRA AGRAWAL SIRSAGANJ SHIKOHABAD 7 09104200065 SK0003751 NEW PUNJAB CYCLE STORE SHIKOHABAD 8 09104200070 SK0001115 ASHOK & SONS BADA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 9 09104200079 SK0004336 SHIV KUMAR GRAIN DEALER SHIKOHABAD 10 09104200084 SK0004045 SHOKARI RAM KHATTRI DIESEL SHIKOHABAD 11 09104200098 SK0003423 OM MEDICAL STORE SHIKOHA BAD 12 09104200107 SK0003990 LALLA BOOK DEPO. KATRA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 13 09104200112 SK0000486 JAY MA.STEEL FURNITURE SERSAGANJ SHIKOHABAD 14 09104200126 SK0005876 AMIT SOAP WORKS SIRSAGANJ SHIKOHABAD 15 09104200131 SK0006151 DEEP MEDICAL HALL SEKOHABAD 16 09104200145 SK0006708 KISHORE EMPORIUM SHIKOHABAD 17 09104200150 SK0006810 SHYAM TIMBER MART SHIKOHABAD 18 09104200159 SK0008042 R.K.CHEMICAL KATRA MEERA SIKOHABAD 19 09104200164 SK0008661 DIMOND HOSIERY SHIKOHABAD 20 09104200178 SK0006895 SRI DURGA OIL IND. ETAH ROAD SHIKOHABAD 21 09104200183 SK0009804 AGARWAL BOOK DEPOT KATRA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 22 09104200197 SK0010062 AGRAWAL PATTAL BHANDAR 37 FOOLS PURIA SKD. 23 09104200206 SK0010199 RAJ PAL TRADERS PANJABI COLONY SHIKOHABAD 24 09104200211 SK0011986 NATIONAL ENGG. WORKS STATION ROAD SHIKOHABAD 25 09104200225 SK0011097 HEERA LAL BACHHI LAL SIRSA GANJ SHIKOHABAD 26 09104200230 SK0011432 SRI AMBEDKAR SIRSA GANJ SHIKOHABAD GRAMODHYOGSEWASANSTHAN 27 09104200239 SK0011518 KRISHNA BOARD MILL MISRANA SKD. 28 09104200244 SK0011508 GAURI SHANKAR PREM NARAYIN BADA BAZAR SHIKOHABAD 29 09104200258 SK0012220 JAIN PACKING INDUSTRIES 635 MISRANA SHIKOHABAD 30 09104200263 SK0012219 PALIWAL GLASS WORKS FIROZABAD ROAD SHIKOHABAD 31 09104200277 SK0002926 PRAKASH MEDICAL STORE SIRSA GANJ SKD. -

Annual-Report-2014-2015-Ministry-Of-Information-And-Broadcasting-Of-India.Pdf

Annual Report 2014-15 ANNUAL PB REPORT An Overview 1 Published by the Publications Division Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India Printed at Niyogi offset Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi 20 ANNUAL 2 REPORT An Overview 3 Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Annual Report 2014-15 ANNUAL 2 REPORT An Overview 3 45th International Film Festival of India 2014 ANNUAL 4 REPORT An Overview 5 Contents Page No. Highlights of the Year 07 1 An Overview 15 2 Role and Functions of the Ministry 19 3 New Initiatives 23 4 Activities under Information Sector 27 5 Activities under Broadcasting Sector 85 6 Activities under Films Sector 207 7 International Co-operation 255 8 Reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and other Backward Classes 259 9 Representation of Physically Disabled Persons in Service 263 10 Use of Hindi as Official Language 267 11 Women Welfare Activities 269 12 Vigilance Related Matters 271 13 Citizens’ Charter & Grievance Redressal Mechanism 273 14 Right to Information Act, 2005 Related Matters 277 15 Accounting & Internal Audit 281 16 CAG Paras (Received From 01.01.2014 To 31.02.2015) 285 17 Implementation of the Judgements/Orders of CATs 287 18 Plan Outlay 289 19 Media Unit-wise Budget 301 20 Organizational Chart of Ministry of I&B 307 21 Results-Framework Document (RFD) for Ministry of Information and Broadcasting 315 2013-2014 ANNUAL 4 REPORT An Overview 5 ANNUAL 6 REPORT Highlights of the Year 7 Highlights of the Year INFORMATION WING advertisements. Consistent efforts are being made to ● In order to facilitate Ministries/Departments in promote and propagate Swachh Bharat Mission through registering their presence on Social media by utilizing Public and Private Broadcasters extensively. -

APPROVED TRAINING CENTRES Center ID Center Name State City District Address Zip Code Job Role Center Manager Email ID Contact Number

APPROVED TRAINING CENTRES Center ID Center Name State City District Address Zip Code Job Role Center Manager Email ID Contact Number 80130 Keshav Uttar Pradesh muzaffarnag Muzaffarnagar Vill Tejalhera, 251307 Trainee Associate Vidhan Singhal [email protected] 9837140332 Polytechnic ar Barla-Basra Road 85950 CH.SANT RAM Haryana karnal Karnal CH.SANT RAM 132041 Trainee Associate SURENDER [email protected] 9416393201 MEMORIAL SR. SEC. SCHOOL KUMAR PUBLIC SR.SEC SCHOOL 86568 Mantra Swami Rajasthan Nohar Hanumangarh Ward no 7 , Near 335523 Trainee Associate Abhishek Solanki [email protected] 9694415086 Vivekanand Skill laxmi ice factory Development Institut 86554 Bigus Skills West Bengal Katiahat North 24 P.O. Katiahat, 743427 Cashier,Trainee Prasun Kanti [email protected] 9851189400 Katiahat Parganas Baduria Basirhat Associate,Sales Biswas road, Dist. 24Prg Associate,Distribu (N), west Bengal tor Salesman 86518 Training Centre Jharkhand karon Deoghar Kusum Bhavan 815357 Store Ops Rakesh Kumar [email protected] 9934379311 Assistant,Cashier, Singh Trainee Associate 84823 Training Center Bihar purnia Purnea Vill- Sukshena, 854203 Store Ops Jitendra Kumar [email protected] 9771232721 Po- Bhatuter Assistant,Sales Mishra chakla, Dist- Associate Purnea 86015 GAYTRI SR.SEC. Haryana karnal Karnal gaytri 132054 Trainee Associate Brij bhushan [email protected] 9466067100 SCHOOL sr.sec.school 85951 AMAR JYOTI Haryana karnal Karnal amar jyoti 132054 Trainee Associate parveen kumar [email protected] 9813136213 SR.SEC.SCHOOL sr.sec.school 82249 Banyan Rajasthan jaipur Jaipur 1&1a, dev nagar, 302015 Trainee Associate Ravi shanker [email protected] 1412711924 edulearning opp. kamal and chouhan solution pvt.ltd. company, gopalpura bypass jaipur 84426 triveni kendra Uttar Pradesh firozabad Firozabad vill. -

Fairs & Festivals, Part VII-B, Vol-XIV, Rajasthan

PRG. 172 B (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XIV .RAJASTHAN PART VII-B FAIRS & FESTIVALS c. S. GUPTA OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan 1966 PREFACE Men are by their nature fond of festivals and as social beings they are also fond of congregating, gathe ring together and celebrating occasions jointly. Festivals thus culminate in fairs. Some fairs and festivals are mythological and are based on ancient traditional stories of gods and goddesses while others commemorate the memories of some illustrious pers<?ns of distinguished bravery or. persons with super-human powers who are now reverenced and idealised and who are mentioned in the folk lore, heroic verses, where their exploits are celebrated and in devotional songs sung in their praise. Fairs and festivals have always. been important parts of our social fabric and culture. While the orthodox celebrates all or most of them the common man usually cares only for the important ones. In the pages that follow an attempt is made to present notes on some selected fairs and festivals which are particularly of local importance and are characteristically Rajasthani in their character and content. Some matter which forms the appendices to this book will be found interesting. Lt. Col. Tod's fascinating account of the festivals of Mewar will take the reader to some one hundred fifty years ago. Reproductions of material printed in the old Gazetteers from time to time give an idea about the celebrations of various fairs and festivals in the erstwhile princely States. Sarva Sbri G. -

CIN Company Name

CIN L40101DL1969GOI005095 Company Name RURAL ELECTRIFICATION CORPORATION LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 16-SEP-2015 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 2551611 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husb Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First and Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD-MON-YYYY) MOHINI SHARMA P K SHARMA D-113 MCD INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 REC0507690 Amount for unclaimed 8.00 22-MAR-2021 COLONY AZADPUR and unpaid dividend DELHI MOHINI SHARMA P K SHARMA D-113 MCD INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 REC0507691 Amount for unclaimed 8.00 22-MAR-2021 COLONY AZADPUR and unpaid dividend DELHI MOHINI SHARMA P K SHARMA D-113 MCD INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 REC0507692 Amount for unclaimed 8.00 22-MAR-2021 COLONY AZADPUR and unpaid dividend DELHI MOHINI SHARMA P K SHARMA D-113 MCD INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 REC0507693 Amount for unclaimed 8.00 22-MAR-2021 COLONY AZADPUR and unpaid dividend DELHI MOHINI SHARMA P K SHARMA D-113 MCD INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 REC0507694 Amount for unclaimed 8.00 22-MAR-2021 COLONY AZADPUR and unpaid dividend DELHI MOHINI SHARMA P K SHARMA D-113 MCD INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110033 REC0507695 Amount for unclaimed -

Punjab National Bank

Punjab National Bank Actual disbursement of subsidy to Units will be done by banks after fulfillment of stipulated terms & conditions Date of issue 27/04/2017 vide sanction order No. 22/CLTUC/RF-14/All Banks/General/2015-16 (Amount in Rs.) Name of the unit Address Amount sanctioned Sl.No for subsidy 1 Ganesh Wood Products Ganesh Wood Products, Village Mehar Majra Tehsil Chachhrauli Distt Yamuna Nagar 825000 2 ROLLEX INDUSTRIES S NO 8/7, SHANTI NAGAR, LANDEWADI, BHOSARI 322734 3 J.P ENGG Works GT Road Bye Pass Hari Singh Nagar Near Transport Nagar Jalandhar 313267 4 Shri Ram Rice Mill Ladwa Road Mathana, Kurukshetra 1312529 5 VINAYAK MARKETING B-51, NEW LOHA MANDI, MACHADA, SIKAR ROAD, JAIPUR 622059 6 SURINDRA AGRO FOODS Bhundri Road, Vill Swadhi Kalan, Mullanpur, Teh Jagraon, Distt Ludhiana - 142026 348675 7 shri ganesh textiles Gali no-3 opp kalia hospital GT Road 143001 164960 8 ARROW ENGINEERING 44 NALANDA ESTATE GIRNAR SCCOTER COMPOUND NR S P RING ROOAD ODHAV 787500 9 Sri Sri Graphics color zone mulavana building,near skyline eleganza flat,G S Road,Kottayam 345415 10 MAHADEV ENTERPRISE C-21 ADRASH-2 GURUDWARA ODHAV 277200 11 KRRISH INTERNATIONAL D-102 FOCL POINT JALANDHAR PUNJAB 120487 12 NAINALIZA KNIT B-VI, 1237/5, ST NO 8, DHOKA MOHALLA, LUDHIANA -141008 421548 13 NEELKAMAL ENTERPRISE 4 ANNAPURNA ESTATE B/H, ZAVERI ESTATE KATHWADA 789375 14 RAJMOTI INDUSTRIES PHASE 3-4/18, CHEHARBHAI DESAI PLOT, NR SAIBABA ESTATE, JADESHWARE ROAD, ADINATHNAGAR ODHAV 807187 15 INDIGO TECHNOLOGIES 7 OLD HAVELLS COMPOUND 14/3 MATHURA ROAD FARIDABAD -

Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

All Rights Reserved Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Book Name: Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Author: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Year of Publication: 2018 Layout: Imtiaz Ali Ansari Publisher: Culture and Tourism Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi Printer: New Indus Printing Press Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Price: Rs.400/- ISBN: 978-969-8100-40-2 Can be had from Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities Department Book shop opposite MPA Hostel Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidaytullah Road Culture and Tourism Department, Karachi-74400 Government of Sindh, Karachi Phone 021-99206073 Dedicated to my mother, Sahib Khatoon (1935-1980) Contents Preface and Acknowledgements 7 Publisher’s Note 9 Introduction 11 1 Prehistoric Circular Tombs in Mol 15 Valley, Sindh-Kohistan 2 Megaliths in Karachi 21 3 Human and Environmental Threats to 33 Chaukhandi tombs and Role of Civil Society 4 Jat Culture 41 5 Camel Art 65 6 Role of Holy Shrines and Spiritual Arts 83 in People’s Education about Mahdism 7 Depiction of Imam Mahdi in Sindhi 97 poetry of Sindh 8 Between Marhi and Math: The Temple 115 of Veer Nath at Rato Kot 9 One Deity, Three Temples: A Typology 129 of Sacred Spaces in Hariyar Village, Tharparkar Illustrations 145 Index 189 8 | Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh | 7 book could not have been possible without the help of many close acquaintances. First of all, I am indebted to Mr. Abdul Hamid Akhund of Endowment Fund Trust for Preservation of the Heritage who provided timely financial support to restore and conduct research on Preface and Acknowledgements megaliths of Thohar Kanarao. -

ROC/DELHI/248(1)/STK-7/6217� Date: 29.10.2019

FORM No. STK — 7 NOTICE OF STRIKING OFF AND DISSOLUTION [Pursuant to sub-section (5) of section 248 of the Companies Act, 2013 and rule 9 of the Companies (Removal of Names of Companies from the Register of Companies) Rules, 2016] Government of India Ministry of Corporate Affairs Office of Registrar of Companies, NCT of Delhi & Haryana IFCI Tower, 4th Floor, 61, Nehru Place, New Delhi —110019. Email: [email protected] Phone: 011-26235703/Fax: 26235702 Notice No- ROC/DELHI/248(1)/STK-7/6217 Date: 29.10.2019 Reference: In the matter of Companies Act, 2013 and 8114 Companies as per list attached as Annexure "A". This is with respect to this Office Notices in Form STK-1 issued on various dates and notice in form STK 5 Public Notice No- ROC-DEL/248(1)/STK- 5/2019/3789 dated 09.08.2019 published in official Gazette on 17.08.2019. Notice is hereby published that pursuant to sub-section (5) of Section 248 of the Companies Act, 2013 the names of 8114 Companies as per list attached as Annexure "A" have this day i.e . 29th day of October, 2019 been struck off from the Register of the Companies and the said Companies are dissolved. (Kamal Harjani) Registrar of Companies NCT of Delhi & Haryana ANNEXURE-A Office of Registrar of Companies, NCT of Delhi & Haryana List of Companies Struck off u/s 248(1) r/w 248(5) of Companies Act, 2013 Sl no CIN Name of Company 1 U74140DL2014PTC272628 100 WEB MEDIA PRIVATE LIMITED 2 U74140DL2013PTC260440 11 LIFEPAL INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED 3 U74140DL2015PTC281219 22STORIEZ ENTERTAINMENT PRIVATE LIMITED 4 U52590DL2015PTC284385 -

Rajasthan GK Quiz – Static GK Notes PDF 2021

Rajasthan GK Quiz – Static GK Notes PDF 2021 Rajasthan have literary meaning ‘The Land of Kings’ is the seventh largest state in country by population. While discussing the location, Rajasthan is located on the northwestern side of India, where it comprises most of the wide Thar Desert (The "Great Indian Desert") Rajasthan - Basic Facts Events Dates & Details State formation Date Formed on 30 March 1949 Reorganized on 1st November 1956 Rajasthan Day 30th March Area 342,239 square kilometres Capital city Jaipur Principal Languages Hindi, Rajasthani, Marwari, Mewari, Jaipuri, Malwi Legislature 200 Lok Sabha Seats 25 Districts 33 Religion Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, Jainism, Christianity, Budhism Rivers Chambal, Sabarmati, Banas, Luni State Flower Rohida (Tecomella undulata) State Animal Camel State Bird Great Indian Bustard State Tree Khejri (Prosopis cineraria) State Fish Mahaseer's – Tigers of rivers Literacy (2011) 66.1% Sex ratio (2011) 928 /1000 Rajasthan Static GK Notes Chief Minister - Ashok Gehlot Governor - Kalraj Mishra The Chief Justice - Indrajit Mahanty Boundaries and Geographic Location Rajasthan shares borders with the Pakistani provinces of Punjab to the northwest and Sindh to the west, along the Sutlej-Indus River valley. Also is bordered by five other Indian states: • Punjab to the north • Haryana and Uttar Pradesh to the northeast • Madhya Pradesh to the southeast • Gujarat to the southwest Geographical location 23.3 to 30.12 North latitude and 69.30 to 78.17 East longitude Tropic of Cancer passing through southernmost tip of the state. Major Cities Udaipur, Bikaner, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Ajmer, Kota Physical Characteristics Aravalli range, the oldest mountain range of India, divides Rajasthan into 2: North-western region - Arid & unproductive Desert in the far west & northwest. -

Pilgrimage to the Abode of a Folk Deity

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Volume 4 Issue 6 Pilgrimages in India: Celebrating Article 8 journeys of plurality and sacredness 2016 Pilgrimage to the Abode of a Folk Deity Rajshree Dhali SGTB Khalsa College, Delhi University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Dhali, Rajshree (2016) "Pilgrimage to the Abode of a Folk Deity," International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: Vol. 4: Iss. 6, Article 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.21427/D7SH9X Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol4/iss6/8 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. © International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage ISSN : 2009-7379 Available at: http://arrow.dit.ie/ijrtp/ Volume 4(vi) 2016 Pilgrimage to the Abode of a Folk Deity Rajshree Dhali SGTB Khalsa College, Delhi University [email protected] Pilgrimage to the shrines of folk deities differ little from pilgrimages to the centres of the institutionalised Gods. However, the historical evolution of a folk cult and the specific socio-cultural context of the emergence and growth of folk deities provides a different dimension to their religious space. This paper examines pilgrimage to the shrine of the folk deity, Goga that attracts followers from across faiths including Hindus and Muslims. The aim of the paper is to explore the double edged religious process at Gogamedi. First, the growing efforts by Hindu Brahmanical traditions to subdue and unsettle divergent traditions of the cult by appropriating it and promoting a monolithic religious culture; second, resistance to these unwelcomed attempts by traditional followers.