Pilgrimage to the Abode of a Folk Deity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government of India Ministry of Tourism

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.†1407 ANSWERED ON 01.07.2019 SCHEMES FOR ECO-TOURISM †1407. SHRI RAMCHARAN BOHRA: SHRI JANARDAN MISHRA: SHRI HEMANT TUKARAM GODSE: SHRI D.K. SURESH: SHRI MANOJ TIWARI: SHRI REBATI TRIPURA: SHRI VIJAY KUMAR DUBEY: Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government has any proposal/sanctioned projects to promote Eco-Tourism in the country and if so, the details thereof, State/UT-wise; (b) the details of the status of projects and the steps taken by the Government in various States/UTs to promote eco-tourism including Madhya Pradesh, Delhi/NCR, Uttar Pradesh and North-Eastern States; (c) whether the Government has any scheme for training in the area of ecotourism to make it popular and made any special efforts for development of Human Resources in the far flung, hilly and backward areas of the country; (d) the Central financial assistance released to various States/UTs during the last three years along with the details of funds actually spent in this regard, State/UT-wise and year- wise; (e) whether the Government has received proposals from various State Governments for development and promotion of eco- tourism and if so, the details thereof and the status of such proposals along with the employment and revenue generated therefrom during the last three years; and (f) whether the Government is considering to provide forest land to start more projects to increase places of tourist interest in hilly areas of the country and if so, the details thereof? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (SHRI PRAHLAD SINGH PATEL) (a) to (f): Ministry of Tourism has identified Eco circuit as one of the fifteen thematic circuits for development under the Swadesh Darshan Scheme. -

Modi Launches Rs One Lakh Cr Fund for Farmers

WWW.YUGMARG.COM FOLLOW US ON REGD NO. CHD/0061/2006-08 | RNI NO. 61323/95 Join us at telegram https://t.me/yugmarg Monday, August 10, 2020 CHANDIGARH, VOL. XXV, NO. 184, PAGES 8, RS. 2 YOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER Haryana CM CM dedicates Rajasthan CM Loyalty above Manohar Lal projects worth confident of everything, launches Anti- Rs. 80 crore in Sullah proving can't wait Bullying campaign of area; Inaugurates PHC majority in for what's to building at Daroh Assembly session Faridabad police come': Kohli on IPL 2020 PAGE 3 PAGE 5 PAGE 6 PAGE 8 Modi launches Rs One lakh cr fund for farmers AGENCY cility of Rs 1 lakh crore under the Agri- their produce, as they will be able to store NEW DELHI, AUG 9 'Kisan Rail' scheme to culture Infrastructure Fund." and sell at higher prices, reduce wastage "In this programme, the sixth install- and increase processing and value addi- Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Sun- benefit farmers ment of the assistance amount under tion. Rs 1 lakh crore will be sanctioned day launched the financing facility of Rs NEW DELHI: Prime Minister Narendra 'PM-Kisan scheme' will also be released. under the financing facility in partnership 1 lakh crore under Agriculture Infra- Modi on Sunday said that the "Kisan Rail" Rs 17,000 crores will be transferred to with multiple lending institutions," read structure Fund and releases the sixth in- scheme will benefit farmers of the entire the accounts of 8.5 crore farmers. The a release by the Prime Minister's Office Badnore tests country as they would be able to sell their stallment of funds under the Pradhan produce in urban areas. -

Title: Shri Pawan Kumar Bansal Presented a Statement of the Estimated Receipt and Expenditure of the Government of India for the Year 2013-14 in Respect of Railways

> Title: Shri Pawan Kumar Bansal presented a statement of the estimated receipt and expenditure of the Government of India for the year 2013-14 in respect of Railways. THE MINISTER OF RAILWAYS (SHRI PAWAN KUMAR BANSAL): . Madam Speaker, I rise to present before this august House the Revised Estimates for 2012-13 and a statement of estimated receipts and expenditure for 2013-14. ...(Interruptions) अय महोदया : या कर रह े ह, अब आप शोर य मचा रह े ह ...(Interruptions) SHRI PAWAN KUMAR BANSAL: I do so with mixed feelings crossing my mind. While I have a feeling of a colossus today, it is only ephemeral and is instantaneously overtaken by a sense of humility. Democracy gives wings to the wingless, cautioning us all the while, that howsoever high or wide our flight may be, we must remain connected to the ground. For giving me this opportunity, I am grateful to the Hon'ble Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh and the UPA Chairperson, Smt. Sonia Gandhi and pay my homage to the sacred memory of Sh. Rajiv Gandhi who introduced me to the portals of the highest Temple of Indian democracy. Madam Speaker, as I proceed, my thought goes to a particularly severe cold spell during the recent winter, when it was snowing heavily in Kashmir valley, and suspension of road and air services had brought life to a grinding halt. Photographs appearing in Newspapers showing a train covered with snow emerging from a similar white background, carrying passengers travelling over the recently commissioned Qazigund - Baramulla section instilled in me a sense of immense pride. -

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

Indian Cultural Events

CALENDAR OF FESTIVALS/EVENTS FOR THE NEXT THREE YEARS Sikkim Name of 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007 -08 Festival/Event Maghe Sankrati Jan 14 & 15 Jan 14 & 15 Jan 14 & 15 Jan 14 & 15 Sonam Lochar Jan 22 Jan 22 Jan 22 Jan 22 Flower Festival February February February February Losar Feb 21 Feb 21 Feb 21 Feb 21 Sakewa May 11 May 11 May 11 May 11 Saga Dawa June 03 June 03 June 03 June 03 Drukpa Tsheshi July 21 July 21 July 21 July 21 Guru Rimpoche’s July 27 July 27 July 27 July 27 Trungkar Tsechu Tendong Lho Rum Aug. 08 Aug. 08 Aug. 08 Aug. 08 Fat Cultural programme Aug. 23 Aug. 23 Aug. 23 Aug. 23 of all the ethnic communities of Sikkim at Limboo Cultural Centre via Jorethang Tharpu, West Sikkim Pang Lhabsol Aug. 30 Aug. 30 Aug. 30 Aug. 30 World Tourism Day Sept. 27 Sept. 27 Sept. 27 Sept. 27 Namchi Mahautsava Oct. 2nd Oct. 2nd week Oct. 2nd week Oct. 2nd week week Durga Puja Oct. 20-25 Oct. 20-25 Oct. 20-25 Oct. 20-25 Lhabab Duechen Nov. 04 Nov. 04 Nov. 04 Nov. 04 Laxmi Puja Nov. 12-15 Nov. 12-15 Nov. 12-15 Nov. 12-15 Id-ul-Fitr Nov. 15 Nov. 15 Nov. 15 Nov. 15 Tourism Festival Dec. 05-11 Dec. 05-11 Dec. 05-11 Dec. 05-11 Losoong Dec. 12-16 Dec. 12-16 Dec. 12-16 Dec. 12-16 Nyempa Guzom Dec. 17-18 Dec. 17-18 Dec. -

List of Candidates Recommended to the Post of LDC in PCDA (NC), Jammu

List of Candidates Recommended to the post of LDC in PCDA (NC), Jammu:- S.No NAME OF THE CATEGORY ROLL No. RANK NOMINATION CANDIDATE STATUS 01 PRIYANKA JINDAL UR 2201007537 1495 Nominated 02 JAI PARKASH UR 2201521044 1566 Nominated 03 ATUL KUMAR UR 2201521419 1601 Nominated 04 KAVITA TRIPATHI UR 3003020032 1637 Incomplete Documents 05 NIRAJ UPADHYAY UR 3003030214 1659 Nominated 06 SUSHANT KUMAT UR 3206020341 1687 Nominated 07 VIKASH KUMAR UR 3206075846 1708 Nominated 08 DEEPAK KUMAR UR 3206123542 1719 Incomplete Documents 09 VIJAY KUMAR OBC 3205006857 2291 Nominated 10 SHASHI BHUSHAN OBC 3206123545 2333 Incomplete KUMAR Documents 11 DHANANJAY KUMAR OBC 3010030643 2362 Incomplete Documents 12 KRISHNA PRASAD OBC 3206007914 2377 Nominated 13 PARTAP SINGH OBC-OH 2201017521 2681 Nominated 14 GANGADHARAN P UR-ExS. 7204700901 2980 Incomplete Documents The dossiers of the above said candidates have been forwarded to following address and the Candidates may enquire for further process from the Concerned office:- Shri Sardari Lal, Dy C.D.A. (AN), O/o The Pr. Cont. of Defence Accounts (NC), Narwal Pain,Satwari, JAMMU (J&K). The Candidates with Incomplete Documents are given a final chance to submit their documents till 21.06.2011 at SSC, NWR Chandigarh otherwise their candidature will be cancelled. List of Candidates Recommended to the post of LDC in M/o External Affairs for their office located in J&K:- NAME OF THE NOMINATION S.No CATEGORY ROLL No. RANK CANDIDATE STATUS 01 KOMAL MITHAL UR 2201620226 1427 Nominated Nominated 02 AKASH GUPTA UR 2201506389 -

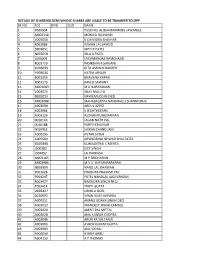

Details of Shareholders Whose Shares Are Liable to Be Transfer to Iepf Sr.No Fol Dpid Clid Name 1 Y000004 Yusufali Alibhaikarimj

DETAILS OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE SHARES ARE LIABLE TO BE TRANSFER TO IEPF SR.NO FOL DPID CLID NAME 1 Y000004 YUSUFALI ALIBHAIKARIMJEE JAWANJEE 2 M003118 MONICA DILAWARI 3 V003054 V CHANDRA SHEKHAR 4 K003086 KISHAN LAL JANGID 5 D003051 DIPTI P PATEL 6 N003058 NILA A PATEL 7 L003009 LACHMANDAS RAMCHAND 8 R003170 RASIKBHAI K SAVJANI 9 G003039 GITA ASHWIN BANKER 10 H003036 HATIM ARIAAR 11 B003056 BHAVANA KAPASI 12 R003173 RAVI D SAWANT 13 M003083 M A NARAYANAN 14 V003075 VIJAY MALLYA 15 N003055 NAYEEMUDDIN SYED 16 M003088 MAHABALAPPA NANDIHALLI SHANMUKHA 17 A003090 ABDUL AZEEZ 18 K003066 K JEGATHEESAN 19 A003126 ASOKAN KUNJURAMAN 20 0010146 JAGAN NATH PAL 21 0010188 PARTH KHAKHAR 22 0010953 SHIKAR CHAND JAIN 23 A000295 AVTAR SINGH 24 A005583 ARVINDBHAI ISHWAR BHAI PATEL 25 G003898 GUNVANTRAI C MEHTA 26 J000382 JEET SINGH 27 J004092 JAI PARKASH 28 M003185 M P SRIDHARAN 29 M003986 M.V.S. SURYANARAYANA 30 N003999 NAND LAL DHAWAN 31 P003628 PRADNYA PRAKASH PAI 32 P004247 PATEL NANDLAL JAGJIVANDAS 33 R003427 RAJENDRA SINGH NEGI 34 T003414 TRIPTI GUPTA 35 U003427 URMILA GOEL 36 0010970 KIRAN VIJAY JAIPURIA 37 A000311 ANANG UDAYA SINGH DEO 38 A003013 AMARJEET SINGH KAMBOJ 39 A003020 AMRIT PAL MITTAL 40 A003028 ANIL KUMAR CHOPRA 41 A003046 ARUN KR SULTANIA 42 A003066 ASHOK KUMAR GUPTA 43 A003983 ANIL GOYAL 44 A004030 A RAJA BABU 45 A004113 A T THOMAS 46 A004564 A. RAJA BABU 47 A004666 ANIL KUMAR LUKKAD 48 A004677 ASHA DEVI 49 A004915 ASHOK GUPTA 50 A005458 ANURAG JAIN 51 A005468 AGA REDDY VANTERU 52 B000031 BHAIRULAL GULABCHAND 53 B000049 BALMUKAND AGARWAL -

The Institution of the Akal Takht: the Transformation of Authority in Sikh History

religions Article The Institution of the Akal Takht: The Transformation of Authority in Sikh History Gurbeer Singh Department of Religious Studies, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The Akal Takht is considered to be the central seat of authority in the Sikh tradition. This article uses theories of legitimacy and authority to explore the validity of the authority and legitimacy of the Akal Takht and its leaders throughout time. Starting from the initial institution of the Akal Takht and ending at the Akal Takht today, the article applies Weber’s three types of legitimate authority to the various leaderships and custodianships throughout Sikh history. The article also uses Berger and Luckmann’s theory of the symbolic universe to establish the constant presence of traditional authority in the leadership of the Akal Takht. Merton’s concept of group norms is used to explain the loss of legitimacy at certain points of history, even if one or more types of Weber’s legitimate authority match the situation. This article shows that the Akal Takht’s authority, as with other political religious institutions, is in the reciprocal relationship between the Sikh population and those in charge. This fluidity in authority is used to explain and offer a solution on the issue of authenticity and authority in the Sikh tradition. Keywords: Akal Takht; jathedar; Sikh institutions; Sikh Rehat Maryada; Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC); authority; legitimacy Citation: Singh, Gurbeer. 2021. The Institution of the Akal Takht: The 1. Introduction Transformation of Authority in Sikh History. Religions 12: 390. https:// The Akal Takht, originally known as the Akal Bunga, is the seat of temporal and doi.org/10.3390/rel12060390 spiritual authority of the Sikh tradition. -

District Census Handbook, Churu, Rajasthan and Ajmer

CENSUS, 195 1 RAJASTHAN AND AJMER DISTRICT CERUS' ,HANDBOOK CHURU PART .-GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND CENSUS TABLES By Pt. YAMUNA LAL DASHORA, B.A., LL.B., Superintendent of Censl1s Operations, Rajasthan and Aimer. JODHPUR: P.RINTED AT THE GOVE]1};llENT PRESS 1956 1f.R:EFAcE, .... ,:, . - , 'The "CensuA Reports' ill' .qlq.en -·times :were printed one for the whole Province. of Ra.j putana and.another for A-jIl1:er-:Merwara._"Soin~ of the Principal 8tates now merged in Rajasthan published 'their own reports. This time the -State Census H eports have been published in the following volumes:- 1. Part I A .. Report. 2. Part 1--B .. ~ubsidiary Tables and District Index of Non-Agricultural Occupations. 3. Part I -C .. Appendices. 4. Part U-A .. r::eneral Population Tables, Household and Age Sample Tables, Social and Cultural Tables, Table E Summary Figures by Administrative Units, and Local 'KA' Infirmities. 5. Part II-B .. Economic Tables. They contain statistics down to the district level The idea of preparing the District Census Handbook separately for each district was put forward .by' Shri R. A. GopaJaswami. I. C. R., Registrar General. India, and ex-officio Census' Commissioner of' India, as part of a plan intended to secu~e an effective, method of preserving the census records prepared for areas below the qistrict level. 'He proposed that all the district, census tables and census abstracts prepared during the process of sorting and cOinpilatiori should be bound together in a single manuscript volume, called the District Census Handbook, and suggested to the State Governments that the Handbook (with or without the addition of other useful information relating to the district) should be printed and pub lished at their own cost in the same manner as the village statistics in the past. -

Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018

Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018 Contradictory Perspectives on Freedom and Restriction of Expression in the context of Padmaavat: A Case Study Ms. Ankita Uniyal, Dr. Rajesh Kumar Significance of Media in Strengthening Democracy: An Analytical Study Dr. Harsh Dobhal, Mukesh Chandra Devrari “A Study of Reach, Form and Limitations of Alternative Media Initiatives Practised Through Web Portals” Ms. Geetika Vashishata Employer Branding: A Talent Retention Strategy Using Social Media Dr. Minisha Gupta, Dr. Usha Lenka Online Information Privacy Issues and Implications: A Critical Analysis Ms. Varsha Sisodia, Prof. (Dr.) Vir Bala Aggarwal, Dr. Sushil Rai Online Journalism: A New Paradigm and Challenges Dr. Sushil Rai Pragyaan: Journal of Mass Communication Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018 Patron Dr. Rajendra Kumar Pandey Vice Chancellor IMS Unison University, Dehradun Editor Dr. Sushil Kumar Rai HOD, School of Mass Communication IMS Unison University, Dehradun Associate Editor Mr. Deepak Uniyal Faculty, School of Mass Communication IMS Unison University, Dehradun Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Subhash Dhuliya Former Vice Chancellor Uttarakhand Open University Haldwani, Uttarakhand Prof. Devesh Kishore Professor Emeritus Journalism & Communication Research Makhanlal Chaturvedi Rashtriya Patrakarita Evam Sanchar Vishwavidyalaya Noida Campus, Noida- 201301 Dr. Anil Kumar Upadhyay Professor & HOD Dept. of Jouranalism & Mass Communication MGK Vidhyapith University, Varanasi Dr. Sanjeev Bhanwat Professor & HOD Centre for Mass Communication University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Copyright @ 2015 IMS Unison University, Dehradun. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission. Application for permission for other use of copyright material including permission to reproduce extracts in other published works shall be made to the publisher. -

Navtej Purewal, Dr Virinder Kalra and Their Interdisciplinary Team, Funded by the Religion and Society Programme

Headline Shrines in India and Pakistan demonstrate shared practices of Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims Summary Gugga Pir (Mairhi) near Patiala, India, where tombs Modern scholars and politicians tend to assume that and folk and spiritual music attract hundreds of the ‘world religions’ are separate and bounded worshippers each week entities with their own unique institutions and texts. State policies reinforce this ‘reality’ by relying upon tools of enumeration and labeling to perpetuate religious difference. The partition of colonial India in 1947 and the mass expulsion of Muslims from East Punjab and a similar movement of Hindus and Sikhs from West Punjab, was an extreme example of the accentuation of religious difference. What this research in the region of Punjab (Pakistan and India) shows, however, is that despite all this, many holy places, shrines and tombs of saints (pirs) are regularly used by Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. This research project was conducted between 2008 and 2010 by Dr Navtej Purewal, Dr Virinder Kalra and their interdisciplinary team, funded by the Religion and Society Programme. Fieldwork took place at a mixture of mainstream and marginal shrine sites in Punjab, and used a combination of surveys, participant observation, ethnography and interviews, as well as study of oratory and music such as qawalli, kirtan and dhadi. The team found that various forms of social exclusion and everyday necessity are addressed through spiritual idioms. In ‘DIY’ shrines and practices the mixing of symbols is common, and self-run rituals and spiritual services exhibit a considerable freedom of interpretation and practice which empowers dalit/low caste groups and women. -

Elizabeth Wickett

Oral Tradition, 27/2 (2012): 333-350 Patronage, Commodification, and the Dissemination of Performance Art: The Shared Benefits of Web Archiving Elizabeth Wickett Introduction This essay addresses the aesthetic and ethical dimensions of documenting oral performance on film, the evolution of a polymodal form of archival documentation leading to online monographs, and the question of how performers may benefit from the archival process— specifically with reference to performances of the epic of Pabuji in Rajasthan, India.1 Owing to digital technology and the emergence of the Internet as a broadcasting forum and marketing agent, a phenomenon has occurred which we might term the “commodification” of expressive culture. In this technological universe where sounds and images are sold for the benefit of some (but not others), issues of copyright, intellectual property rights, and the commercialization and marketing of expressive culture on the web have become paramount.2 Video excerpts are being broadcast around the world in free and open formats.3 Whereas documentation of oral performance traditions by scholars and for scholars was once the norm, I propose that we—as ethnographers, linguists, and folklorists—must ensure that such performers can also benefit from the process of academic study and documentation, with support for the perpetuation of their livelihood as well as their cultural and artistic legacy. How do we as scholars and ethnographic filmmakers respond to these challenges and use these media to the performers’ benefit? 1 I am very grateful to the Firebird Foundation for Anthropological Research for their funding of the filming and archival documentation of four performances of the oral epic of Pabuji ki par across Rajasthan in 2008 and its production as five films in 2009 (Wickett 2009).