When Old Meets New: Some Perspectives on Recent Chinese Legal Developments and Their Relevance to the United States (The Importance of Labor Law)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

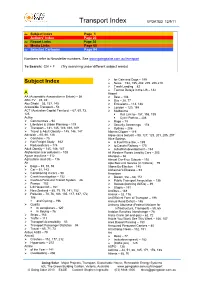

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

UNAA Media Peace Awards Winners and Finalists

UNAA Media Peace Awards WINNERs and FINALISTs 2016_____________________________________________ Print WINNER Paul Farrell, Nick Evershed, Helen Davidson, Ben Doherty, David Marr and Will Woodward, Guardian Australia, The Nauru Files FINALIST Ben Doherty, Guardian Australia, Lives in Limbo FINALIST SBS, Something Terrible Has Happened to Levai FINALIST Adam Morton, The Age, The Vanishing Island TV – News/Current Affairs WINNER SBS World News, Syria, Five Years of Crisis FINALIST Phil Goyen and Michael Usher, 60 Minutes, Divided States of America FINALIST Jane Bardon, ABC News and Current Affairs, Australia’s Third World Indigenous Housing Shame FINALIST Waleed Aly and Tom Whitty, The Project, ISIL is Weak TV – Documentary WINNER Caro Meldrum-Hanna, Mary Fallon, Elise Worthington, Four Corners, Australia’s Shame FINALIST Brett Mason, Calliste Weitenberg, Bernadine Lim, Jonathan Challis, Micah McGown, Dateline, Allow Me to Die FINALIST Patrick Abboud, Breaking Point, Bullying’s Deadly Toll Radio – News WINNER Jane Bardon, ABC News, Indigenous Residents FINALIST Sue Lannin, ABC Radio National, East Timor Hitlist Radio – Documentary WINNER Christine El-Khoury, ABC News and Current Affairs, Anti-Muslim extremists: How far will they go? FINALIST Dan Box and Eric George, The Australian, Bowraville FINALIST Kristina Kukolja and Lindsey Arkley, SBS, Unwanted Australians FINALIST Jo Chandler, Wendy Carlisle, Tim Roxburgh, Linda McGinnes, ABC Radio National, Ebola with wings: The TB crisis on our doorstep Photojournalism WINNER Darrian Traynor, Gaza’s -

Section 3: China's Domestic Stability

SECTION 3: CHINA’S DOMESTIC STABILITY Introduction Twenty-five years after the Tiananmen Square massacre, many of the same underlying causes of unrest persist today. Land sei- zures, labor disputes, wide-scale corruption, cultural and religious repression, and environmental degradation have led to hundreds of thousands of localized protests annually throughout China since 2010. The Chinese leadership has consistently responded to in- creased unrest with repression, censorship, and, occasionally, lim- ited accommodation. Over the past year, ethnic unrest escalated in response to excessive force by China’s internal security forces and the growing radicalization of disenfranchised Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Militant Uyghur separatists also shifted their tactics from attacking Chinese authorities to tar- geting civilians and public spaces. President Xi Jinping, like his predecessors, has made the preser- vation of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule and domestic sta- bility his top priorities. He has issued a series of policy directives and institutional changes to centralize the domestic stability main- tenance apparatus under his personal oversight and to expand its scope and capabilities. The growth of Internet connectivity and social media in China has provided Chinese citizens with new tools to express grievances and organize larger, more numerous, and better coordinated pro- tests. To contain this rising threat to authority, President Xi has instituted new constraints on Internet criticism of the CCP, launched high-profile judicial cases against popular online com- mentators and advocates, and further tightened news media and Internet controls. This section—based on a Commission hearing in May 2014 on China’s domestic stability and briefings by U.S. -

Morphology and Typology of China Correspondents: a Habitus-Based Approach

This is a repository copy of Morphology and typology of China correspondents: A habitus-based approach. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/145233/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Zeng, Y orcid.org/0000-0003-1379-7840 (2018) Morphology and typology of China correspondents: A habitus-based approach. Journalism. ISSN 1464-8849 https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918804910 © The Author(s) 2018. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Journalism. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Morphology and Typology of China Correspondents 1 Morphology and typology of China correspondents: a habitus-based approach Zeng, Y. (2018). Morphology and typology of China correspondents: A habitus-based approach. Journalism, doi: 1464884918804910 Abstract Drawing on Bourdieu’s field theory and his key construct of habitus, this study examines the “Chinese habitus” and “journalistic habitus” of China correspondents, and proposes a habitus-based typology. -

Digital Authoritarianism, China and Covid

ANALYSIS Digital Authoritarianism, China and C0VID LYDIA KHALIL NOVEMBER 2020 DIGITAL AUTHORITARIANISM, CHINA AND COVID The Lowy Institute is an independent policy think tank. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia — economic, political and strategic — and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high-quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Analyses are short papers analysing recent international trends and events and their policy implications. The views expressed in this paper are entirely the author's own and not those of the Lowy Institute. ANALYSIS DIGITAL AUTHORITARIANISM, CHINA AND COVID EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The combination of retreating US leadership and the COVID-19 pandemic has emboldened China to expand and promote its tech- enabled authoritarianism as world’s best practice. The pandemic has provided a proof of concept, demonstrating to the CCP that its technology with ‘Chinese characteristics’ works, and that surveillance on this scale and in an emergency is feasible and effective. With the CCP’s digital authoritarianism flourishing at home, Chinese-engineered digital surveillance and tracking systems are now being exported around the globe in line with China’s Cyber Superpower Strategy. China is attempting to set new norms in digital rights, privacy, and data collection, simultaneously suppressing dissent at home and promoting the CCP’s geostrategic goals. -

No.12 2013 American Review Global Perspectives on AMERICA / MAY–AUG 2013 / ISSUE 12

American Review GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES ON AMERICA American renewal Clyde Prestowitz on how the shale gas revolution is a global game changer PLUS Megan MacKenzie on women in combat John Lee on the new China myth Steven Hayward on Barack Obama’s brown climate agenda No.12 2013 American Review GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES ON AMERICA / MAY–AUG 2013 / ISSUE 12 American Opinion 5 Containment versus prevention Tom Switzer What the Boston terror and the North Korean nuclear tests mean 10 Paradox of Pakistan Anatol Lieven The perils of close security ties between Washington and Islamabad 16 The downside to globalisation Richard C. Longworth What ails the new white underclass in Middle America Cover Story 20 Don’t write off America (again) AMErican Clyde Prestowitz RENEwal A former high-profile pessimist does a volte face on US economic decline 28 The Pentagon’s gender U-turn Megan H. MacKenzie An afterword to the author’s groundbreaking article on women in combat in the distinguished Foreign Affairs magazine American 2 Review American Review GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES ON AMERICA / MAY–AUG 2013 / ISSUE 12 Cover Story 37 Obama won’t lead on climate change Steven F. Hayward Prospects for a legally binding and enforceable post-Kyoto global treaty are zero 46 The new China myth John Lee Flirting with Beijing does not amount to snubbing Australia’s great and powerful friend 54 Marshall Green’s legacy James Curran A leading diplomat knew that America should play the role of stabiliser, not crusader, in the Asia-Pacific Book Reviews 66 The future world Ramesh Thakur Few -

Images of China: a Comparative Framing Analysis of Australian Current Affairs Programming

Intercultural Communication Studies XXI: 1 (2012) LI Images of China: A Comparative Framing Analysis of Australian Current Affairs Programming Xiufang (Leah) LI Hanshan Normal University, China Abstract: Research into China’s image in Australia is helpful to promote the mutual understanding and the bilateral relations between the two countries. Informed by national image theory and media framing theory, this study uses content analysis and framing analysis to explore the prestigious current affairs programs: Foreign Correspondent produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and Dateline by Special Broadcasting Service. It examines both the frames and the framing patterns used by the two programs in their coverage of China in the past ten years. The study looks into the structures of theme, syntax, script and rhetoric of the episodes. The results show that both programs represent China negatively in a political sense, but neutrally in economic and environmental terms. However, Foreign Correspondent portrays China favourably regarding the cultural aspect. Framing devices are evident, including presentation format, animal images, ideological words, the public memory of the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. The analysis argues that Foreign Correspondent and Dateline serve the mission to build the Australian national identity as well as attempt to present a balanced picture of China, as stronger economic ties are developed and frequent cultural exchanges are encouraged. Framing techniques, however, have been consciously or unconsciously influenced by historical stereotypes and the conventional fear of communism expressed during the past two centuries. Keywords: National image, framing, the ABC and SBS, current affairs 1. Introduction China’s emergence has increasingly enhanced its media exposure in the world. -

The Influence Environment: a Survey of Chinese-Language Media

The influence environment A survey of Chinese-language media in Australia Alex Joske, Lin Li, Alexandra Pascoe and Nathan Attrill Policy Brief Report No. 42/2020 About the authors Alex Joske is an analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Lin Li is a researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Alexandra Pascoe is a research intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Nathan Attrill is a researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank John Fitzgerald, Danielle Cave, Louisa Lim, Michael Shoebridge, Peter Jennings and several anonymous peer reviewers who offered their feedback and insights. Audrey Fritz contributed research on media regulation and censorship. The Department of Home Affairs provided ASPI with $230k in funding, which was used towards this report. What is ASPI? The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally. ASPI’s sources of funding are identified in our annual report, online at www.aspi.org.au and in the acknowledgements section of individual publications. ASPI remains independent in the content of the research and in all editorial judgements. ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) is a leading voice in global debates on cyber, emerging and critical technologies, issues related to information and foreign interference and focuses on the impact these issues have on broader strategic policy. -

2008-2009 Annual Report (Complete Report)

connect Annual Report 2009 engage Re definingthe town square belong improve support Sarah, Victoria and Amy love taking time out from study to catch up on Once, the town square was a all the latest. Whether it’s watching last night’s episode of The Chaser, place where people gathered downloading a triple j pod or vod, to talk and exchange ideas. or grabbing a movie review on ABC Mobile, wherever they are, the ABC is their town square. Now, the ABC is redefining the town square as a world of greater opportunities: a world where Australians can engage with one another and explore the ideas and events that are shaping our communities, our nation and beyond. A world where people can come to speak and be heard, to listen and learn from each other. 2008–09 at a Glance 2 In this report The National Broadcaster 4 Letter of Transmittal 6 Corporate Report 7 SECTION 1 ABC Vision, Mission and Values 7 Corporate Plan Summary 8 ABC Board of Directors 10 Board Directors’ Statement 14 ABC Advisory Council 18 Significant Events in 2008–09 22 The Year Ahead 24 Magazine 25 Overview 38 SECTION ABC Audiences 38 2 ABC Services 53 ABC in the Community 56 ABC People 60 Commitment to a Greener Future 65 Corporate Governance 68 Corporate Sustainability 74 Financial Summary 76 ABC Divisional Structure 79 SECTION ABC Divisions 80 3 Radio 80 Television 85 News 91 Innovation 95 ABC International 98 ABC Commercial 102 Operations Group 106 People and Learning 110 Corporate 112 SECTION 4 Summary Reports 121 Performance Against the ABC Corporate Plan 2007–10 121 Outcomes and Outputs 133 SECTION Independent Auditor’s Report 139 5 Financial Statements 141 Appendices 187 Index 247 Glossary 250 ABC Charter and Duties of the Board 251 1 Radio–8 760 radio hours on each network and station. -

China Media Bulletin

CHINA MEDIA BULLETIN A weekly update of press freedom and censorship news related to the People’s Republic of China Issue No. 71: October 11, 2012 Headlines State-friendly novelist wins Nobel, peace laureate remains in prison Chinese users critique, praise U.S. presidential debate ‘World of Warcraft’ fans bemoan censorship, state TV’s addiction tale Blogger self-immolates, Australian TV crew reaches restricted Tibetan areas U.S. House panel says Huawei and ZTE pose security threat PHOTO OF THE WEEK: A SHOE FOR FREE SPEECH Credit: Wall Street Journal BROADCAST / PRINT MEDIA NEWS State-friendly novelist wins Nobel, peace laureate remains in prison On October 11, the Swedish Academy announced that it had selected Chinese novelist Mo Yan as the winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize for literature, citing his development of a writing style that “merges folk tales, history, and the contemporary.” China’s state media cheered the news, as it marked the first time that a Nobel award was given to a Chinese national who is friendly with the authoritarian government. China’s last winner, 2010 Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, remains in prison for his advocacy of democracy. Previous Chinese-born Nobel recipients had won their awards after emigrating. According to prominent human rights lawyer Teng Biao, at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2009, Mo had refused to sit in a seminar with dissident Chinese writers Dai Qing and Bei Ling. When asked in the past about Liu’s 11-year prison sentence, Mo had claimed he did not know much about it and had nothing to say. -

E. [email protected] Rmkcrew.Com.Au ROBERT HILL ACS

6 Ridge St, North Sydney, NSW 2060 p. +61 2 8458 1300 | e. [email protected] rmkcrew.com.au ROBERT HILL ACS Cinematographer/Director of Photography EMPLOYMENT SUNDAY NIGHT, NETWORK 7 • Sydney, Australia February 2016 – November 2019 Cinematographer for Network 7’s Sunday Night programme. I have travelled around Australia and the world with presenters and producers filming unique stories in amazing locations, as well as interviewing celebrities and producing amazing human interest films. Highlights include a seven-day marathon across the Sahara in Morocco, filming polar bears and icebergs in Canada, a film about Indonesia’s Mount Ijen volcano and sulphur mining, a film with the remote Kombai tribe in the Papuan jungle, covering the illegal gold mining and deforestation of the Peruvian Amazon rainforest, filming the land speed record for a blind person on a motorbike (on Lake Gairdner in South Australia), trekking the MacDonnell Ranges in Central Australia for White Ribbon’s ‘Trek for Respect’ and a docu-drama film about the sinking of the Blythe Star ship off the Tasmanian coast. Using the latest 4K cameras, cine lenses, macro, gimbals, tracks & sliders, drones, lighting systems, green screen and time-lapse techniques. Assignments have taken me from the boardroom to the world's deserts, jungles, polar regions, mountains, oceans, natural disaster zones and cities to create world-class images and films. At the 2018 ACS National Awards I was proud to receive an award for Distinction in Cinematography in both the Dramatised Documentaries and Entertainment/Magazine sections for 'The Last Survivor – Blythe Star' and ‘Morocco Marathon’.