Section 3: China's Domestic Stability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 China Beat Archive 6-22-2008 Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons "Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary" (2008). The China Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012. 205. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive/205 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the China Beat Archive at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Jesus in China—Evan Osnos on an Upcoming Frontline Documentary June 22, 2008 in Watching the China Watchers by The China Beat | No comments The Public Broadcasting Corporation’s Frontline series has a long tradition of airing documentaries on China. Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon’s prize-winning look at 1989, “The Gate of Heavenly Peace,” was shown as part of the series, for example, as was a later Tiananmen documentary, “The Tank Man.” And thanks to the online extras, from guides to further reading to lesson plans for teachers, the PBS Frontline site has become a valuable resource for those who offer classes or simply want to learn about the PRC. Still, it is rare (probably unprecedented) for two China shows to run back-to-back on Frontline. -

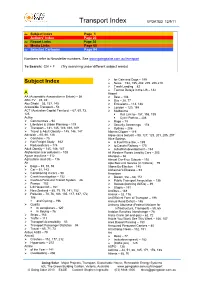

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China's

C O R P O R A T I O N Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China’s Aerospace Forces Selections from the Inaugural Conference of the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) Edmund J. Burke, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, Mark R. Cozad, Timothy R. Heath For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF340 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9549-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface On June 22, 2015, the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), in conjunction with Headquarters, Air Force, held a day-long conference in Arlington, Virginia, titled “Assessing Chinese Aerospace Training and Operational Competence.” The purpose of the conference was to share the results of nine months of research and analysis by RAND researchers and to expose their work to critical review by experts and operators knowledgeable about U.S. -

American Government (POL SC 1100) Spring 2019 Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 2-2:50Pm 102 Naka Hall

POL SC 1100-1-1-1-1 American Government (POL SC 1100) Spring 2019 Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 2-2:50pm 102 Naka Hall Jake Haselswerdt, PhD Assistant Professor Department of Political Science & Truman School of Public Affairs Office: 301 Professional Building Office hours: Tuesday, 2-4pm, and by appointment Email (preferred): [email protected] Phone: 573-882-7873 Syllabus updated February 15, 2019 Teaching Assistants Hyojong Ahn Dongjin Kwak Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Office: 315 Professional Building Office: 207 Professional Building Office hours: Monday, 10:30am-1:30pm; Office hours: Monday & Wednesday, Tuesday, 12:30pm-3:30pm 10am-1pm Course Overview & Goals This course offers an introduction to American politics and government from a political science perspective. While the course should increase your factual civic knowledge of American institutions, it is about more than that. Political science seeks to move beyond civic knowledge, to question and analyze the people, groups, events, institutions, policies, ideas, etc that we observe. Sometimes, our questions are empirical, meaning they deal with what is: Do Members of Congress support the policies their constituents want? Do political campaigns affect voters’ decisions? Sometimes, they are normative, meaning they deal with what should be: Is the U.S. Senate harmful to democracy because Wyoming has the same number of senators as California? Should the Constitution be amended so Supreme Court Justices no longer serve for life? In this course, we will consider both types of questions. 1 POL SC 1100-1-1-1-1 The success of democratic governments depends in part on the capacity of their citizens to hold them accountable. -

Internet Freedom in China: U.S. Government Activity, Private Sector Initiatives, and Issues of Congressional Interest

Internet Freedom in China: U.S. Government Activity, Private Sector Initiatives, and Issues of Congressional Interest Patricia Moloney Figliola Specialist in Internet and Telecommunications Policy May 18, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45200 Internet Freedom in China: U.S. Government and Private Sector Activity Summary By the end of 2017, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had the world’s largest number of internet users, estimated at over 750 million people. At the same time, the country has one of the most sophisticated and aggressive internet censorship and control regimes in the world. PRC officials have argued that internet controls are necessary for social stability, and intended to protect and strengthen Chinese culture. However, in its 2017 Annual Report, Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières, RSF) called China the “world’s biggest prison for journalists” and warned that the country “continues to improve its arsenal of measures for persecuting journalists and bloggers.” China ranks 176th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2017 World Press Freedom Index, surpassed only by Turkmenistan, Eritrea, and North Korea in the lack of press freedom. At the end of 2017, RSF asserted that China was holding 52 journalists and bloggers in prison. The PRC government employs a variety of methods to control online content and expression, including website blocking and keyword filtering; regulating and monitoring internet service providers; censoring social media; and arresting “cyber dissidents” and bloggers who broach sensitive social or political issues. The government also monitors the popular mobile app WeChat. WeChat began as a secure messaging app, similar to WhatsApp, but it is now used for much more than just messaging and calling, such as mobile payments, and all the data shared through the app is also shared with the Chinese government. -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

The Limits of Commercialized Censorship in China

The Limits of Commercialized Censorship in China Blake Miller∗ September 27, 2018 Abstract Despite massive investment in China's censorship program, internet platforms in China are rife with criticisms of the government and content that seeks to organize opposition to the ruling Communist Party. Past works have attributed this \open- ness" to deliberate government strategy or lack of capacity. Most, however, do not consider the role of private social media companies, to whom the state delegates information controls. I suggest that the apparent incompleteness of censorship is largely a result of principal-agent problems that arise due to misaligned incentives of government principals and private media company agents. Using a custom dataset of annotated leaked documents from a social media company, Sina Weibo, I find that 16% of directives from the government are disobeyed by Sina Weibo and that disobedience is driven by Sina's concerns about censoring more strictly than com- petitor Tencent. I also find that the fragmentation inherent in the Chinese political system exacerbates this principal agent problem. I demonstrate this by retrieving actual censored content from large databases of hundreds of millions of Sina Weibo posts and measuring the performance of Sina Weibo's censorship employees across a range of events. This paper contributes to our understanding of media control in China by uncovering how market competition can lead media companies to push back against state directives and increase space for counterhegemonic discourse. ∗Postdoctoral Fellow, Program in Quantitative Social Science, Dartmouth College, Silsby Hall, Hanover, NH 03755 (E-mail: [email protected]). 1 Introduction Why do scathing criticisms, allegations of government corruption, and content about collective action make it past the censors in China? Past works have theorized that regime strategies or state-society conflicts are the reason for incomplete censorship. -

Human Rights in China and U.S. Policy: Issues for the 117Th Congress

Human Rights in China and U.S. Policy: Issues for the 117th Congress March 31, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46750 SUMMARY R46750 Human Rights in China and U.S. Policy: Issues March 31, 2021 for the 117th Congress Thomas Lum U.S. concern over human rights in China has been a central issue in U.S.-China relations, Specialist in Asian Affairs particularly since the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989. In recent years, human rights conditions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have deteriorated, while bilateral tensions related to trade Michael A. Weber and security have increased, possibly creating both constraints and opportunities for U.S. policy Analyst in Foreign Affairs on human rights. After consolidating power in 2013, Chinese Communist Party General Secretary and State President Xi Jinping intensified and expanded the reassertion of party control over society that began toward the end of the term of his predecessor, Hu Jintao. Since 2017, the government has enacted new laws that place further restrictions on civil society in the name of national security, authorize greater controls over minority and religious groups, and further constrain the freedoms of PRC citizens. Government methods of social and political control are evolving to include the widespread use of sophisticated surveillance and big data technologies. Arrests of human rights advocates and lawyers intensified in 2015, followed by party efforts to instill ideological conformity across various spheres of society. In 2016, President Xi launched a policy known as “Sinicization,” under which the government has taken additional measures to compel China’s religious practitioners and ethnic minorities to conform to Han Chinese culture, support China’s socialist system as defined by the Communist Party, abide by Communist Party policies, and reduce ethnic differences and foreign influences. -

IITM CSC Article #76 14 August 2014 Xinjiang Conflict and Its

IITM CSC Article #76 14 August 2014 Xinjiang Conflict and its Changing Nature Avinash Godbole, Research Assistant, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. Violence returned to Xinjiang immediately after the month of Ramadan as more than a hundred people were killed in violence spanning last ten days. Unofficial estimates put the number of deaths at 1000, making this perhaps the bloodiest episode in the contemporary history of Xinjiang. Extremists also killed Jume Tahir, the government appointed Imam of China’s largest mosque. While the Xinjiang problem has been going on for a long time, 2014 has become one of the most violent years in the recent past as more than 250 people have been killed in various incidents of violent attacks. In 2013, according to official estimates, ethnic clashes had claimed 110 lives. These figures are contested arguing that China would not reveal the true scale of violence in Xinjiang to the outside world. 2014 has also had many other firsts as far as Xinjiang extremist violence is concerned. In an attack on a marketplace in the provincial capital Urumqi, 42 people were killed in what was the single largest death count in an incident of extremism inside China. Earlier in March this year, 29 people were killed in knife attacks targeting train travelers in the Kunming main railway station. In October there was an attack on Tiananmen Square that reportedly caused three deaths as suicide bombers crashed and exploded their SUV into a security barricade. What’s new about the violent incidents in the past two years is that ordinary citizens are being targeted unlike earlier when police stations and government offices were the primary targets of extremist violence. -

Uyghur Identity Contestation and Construction of Identity in a Conflict Setting

UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG School of Global Studies = Uyghur Identity Contestation and Construction of Identity in a Conflict Setting Master Thesis in Global Studies Spring Semester 2015 Author: Fanny Olson Supervisor: Camilla Orjuela ABSTRACT This study explores and discusses the dynamics of identity in conflict through examining Uyghur collective identity in the specific context of China as an emerging power. Particular attention is paid to how this identity is constructed and contested by different actors of the Xinjiang Conflict. The Xinjiang Conflict is a multifaceted conflict, consisting of both direct and structural violence. These dynamics of identity are based on different understandings of what it means to be a Uyghur, which is in line with existing research on contemporary conflicts that considers identity as a driving force of violence. Through a text analysis, this study sets out to assess how Uyghur identity is constructed and contested in the context of the Xinjiang Conflict, by primary actors; the Chinese government, Uyghur diaspora and the local Uyghur population in Xinjiang. As the Uyghurs’ identity has been contested, and discontent is cultivated among the Uyghur community, the conflict between Uyghurs and the Chinese government (dominated by the majority ethnic group Han Chinese) has escalated since the mid-1990s. The findings advanced in this research conclude that Uyghur identity, in the context of conflict, is contested within different areas, such as language, culture, territory, religion and even time. This paper suggests that within these areas, identity is contested though the different processes of negotiation, resistance, boundary-making and emphasis on certain features of ones identity. -

Asia's Energy Security

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #68 | november 2017 asia’s energy security and China’s Belt and Road Initiative By Erica Downs, Mikkal E. Herberg, Michael Kugelman, Christopher Len, and Kaho Yu cover 2 NBR Board of Directors Charles W. Brady Ryo Kubota Matt Salmon (Chairman) Chairman, President, and CEO Vice President of Government Affairs Chairman Emeritus Acucela Inc. Arizona State University Invesco LLC Quentin W. Kuhrau Gordon Smith John V. Rindlaub Chief Executive Officer Chief Operating Officer (Vice Chairman and Treasurer) Unico Properties LLC Exact Staff, Inc. President, Asia Pacific Wells Fargo Regina Mayor Scott Stoll Principal, Global Sector Head and U.S. Partner George Davidson National Sector Leader of Energy and Ernst & Young LLP (Vice Chairman) Natural Resources Vice Chairman, M&A, Asia-Pacific KPMG LLP David K.Y. Tang HSBC Holdings plc (Ret.) Managing Partner, Asia Melody Meyer K&L Gates LLP George F. Russell Jr. President (Chairman Emeritus) Melody Meyer Energy LLC Chairman Emeritus Honorary Directors Russell Investments Joseph M. Naylor Vice President of Policy, Government Lawrence W. Clarkson Dennis Blair and Public Affairs Senior Vice President Chairman Chevron Corporation The Boeing Company (Ret.) Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA U.S. Navy (Ret.) C. Michael Petters Thomas E. Fisher President and Chief Executive Officer Senior Vice President Maria Livanos Cattaui Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc. Unocal Corporation (Ret.) Secretary General (Ret.) International Chamber of Commerce Kenneth B. Pyle Joachim Kempin Professor; Founding President Senior Vice President Norman D. Dicks University of Washington; NBR Microsoft Corporation (Ret.) Senior Policy Advisor Van Ness Feldman LLP Jonathan Roberts Clark S. -

Chinabrief in a Fortnight

ChinaBrief Volume XIV s Issue 13 s July 3, 2014 VOLUME XIV s ISSUE 13 s JULY 3, 2014 In This Issue: IN A FORTNIGHT Brief by David Cohen 1 WITH ZHOU’S CIRCLE DOWN, XI’S PURGE MAY TURN TO HU By Willy Lam 3 CHINA’S STRATEGIC ROCKET FORCE: SHARPENING THE SWORD (PART 1 OF 2) By Andrew S. Erickson and Michael S. Chase 6 China’s PLA Second Artillery appears more confident, having made progress CHINESE HIGH SPEED RAIL LEAPFROG DEVELOPMENT on the “conventionalization of deter- By Clark Edward Barrett 10 rence” (Source: China Military Online) INDONESIA AVOIDS OPEN TERRITORIAL DISPUTE WITH CHINA, DESPITE CONCERNS China Brief is a bi-weekly jour- By Prashanth Parameswaran 13 nal of information and analysis CORRECTIONS 16 covering Greater China in Eur- asia. China Brief is a publication of In a Fortnight The Jamestown Foundation, a private non-profit organization ON PARTY’S BIRTHDAY, PROMISES OF A CONTINUED PURGE based in Washington D.C. and is edited by David Cohen. By David Cohen The opinions expressed in China Brief are solely those On the 93rd anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party of the authors, and do not (CCP), General Secretary Xi Jinping highlighted his campaign to fight corruption necessarily reflect the views of and improve cadres’ “work style,” making it the focus of a speech delivered at The Jamestown Foundation. a Politboro meeting the day before the anniversary (Xinhua, June 30). Official commentary surrounding top-level arrests approved at the same meeting makes it clear that this purge is intended to continue indefinitely.