The Influence Environment: a Survey of Chinese-Language Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

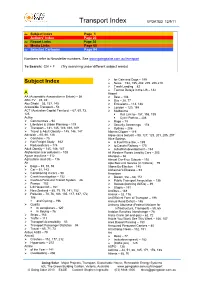

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Joint Civil Society Report Submitted to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

Joint Civil Society Report Submitted to The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination for its Review at the 96th Session of the combined fourteenth to seventeenth periodic report of the People’s Republic of China (CERD/C/CHN/14-17) on its Implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination Submitters: Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) is a coalition of Chinese and international human rights non-governmental organizations. The network is dedicated to the promotion of human rights through peaceful efforts to push for democratic and rule of law reforms and to strengthen grassroots activism in China. [email protected] https://www.nchrd.org/ Equal Rights Initiative is a China-based NGO monitoring rights development in Western China. For the protection and security of its staff, specific identification information has been withheld. Date of Submission: July 16, 2018 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary Paras. 1-2 II. Recommendations Para. 3 III. Thematic Issues & Findings A. Legislation underpinning discriminatory counter-terrorism policies Paras. 4-7 [Articles 2 (c) and 4; List of Themes para. 8] B. Militarized policing, invasive surveillance, and constant monitoring Paras. 8-21 [Articles 3, 4, and 5 (a-b); LOT para. 22] C. Extrajudicial detention, forced disappearances, torture, and other abuses Paras. 22-28 in “Re-education” camps [Article 5 (a)(b)(d); LOT para. 21] D. Counter-terrorism used to justify arbitrary detention and discriminatory Paras. 29-34 punishment of ethnic minorities [Articles 4 and 5 (a)(b)(d); LOT paras. 6 and 21] E. Discrimination and restrictions on religious freedom Paras. -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

New Immigrants Improving Productivity in Australian Agriculture

New Immigrants Improving Productivity in Australian Agriculture By Professor Jock Collins (UTS Business School), Associate Professor Branka Krivokapic-Skoko (CSU) and Dr Devaki Monani (ACU) New Immigrants Improving Productivity in Australian Agriculture by Professor Jock Collins (UTS Business School), Associate Professor Branka Krivokapic-Skoko (CSU) and Dr Devaki Monani (ACU) September 2016 RIRDC Publication No 16/027 RIRDC Project No PRJ-007578 © 2016 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-873-9 ISSN 1440-6845 New Immigrants Improving Productivity in Australian Agriculture Publication No. 16/027 Project No. PRJ-007578 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the CommonWealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, Whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

Sydney Dog Lovers Show 2018

SYDNEY DOG LOVERS S H O W 2 0 1 8 PUBLIC RELATIONS CAMPAIGN May to August 2018 COVERAGE RESULTS. 87 48 35 18 ONLINE PIECES PRINT PIECES SOCIAL PIECES BROADCAST PIECES Online coverage was achieved Print coverage was achieved across 42 Social media coverage was Broadcast coverage was achieved across 63 individual platforms individual publications including leading achieved across all major platforms across leading television and radio including Newscorp and Fairfax New South Wales newspapers The Daily including Facebook, Instagram, stations including Channel 10, digital sites as well as key ‘What’s Telegraph, News Local (group-wide) and Twitter and WeChat. Many online Weekend TODAY, ABC News, ABC On Sydney’ sites including City of Sydney Morning Herald. Coverage was also platforms syndicated their Radio and Nova 96.9. Sydney, Broadsheet, Time Out, achieved in leading national magazines such coverage across social channels Concrete Playground and the as MiNDFOOD, Total Girl and 50 Something including AWOL (Junkee media), Urban List. as well as CALD publications including the Urban List, Time Out and Vision China Times Sydney and Australian Concrete Playground. Jewish News Sydney. TOTAL PIECES OF MEDIA COVERAGE ACHIEVED: 204 AUDIENCE. TOTAL CUMULATIVE AUDIENCE OF ALL 204 MEDIA ARTICLES: 83,189,957* INCREASE IN VOLUME OF COVERAGE FROM 2017 (196 MEDIA ARTICLES) INCREASE IN 2017 AUDIENCE (82,571,700) ONLINE CONTINUES TO BE OUR STRONGEST AUDIENCE FOLLOWED BY PRINT *Official audience and circulation figures sourced from Medianet and Slice Media Monitoring AUDIENCE. 68,213,304 2,785,793 1,674,302 5,930,753 ONLINE CIRCULATION PRINT CIRCULATION SOCIAL AUDIENCE BROADCAST AUDIENCE Online circulation was achieved on Print circulation was achieved through Many media news and lifestyle ABC News Sydney has a robust leading digital sites with high volume leading New South Wales newspapers titles push out their news articles audience of over 800,000, which average unique audiences (AUV). -

Australians at War Film Archive James Cruickshank

Australians at War Film Archive James Cruickshank (Jim) - Transcript of interview Date of interview: 3rd October 2003 http://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au/archive/770 Tape 1 00:43 Well, I was baptised Andrew James Cruickshank, born on the 24th of March 1929, in Glasgow, Scotland, where my father at the time was a policeman with the northern division of the Glasgow Police Force. And I was 01:00 born at Mary Hill, which was not then a very salubrious suburb, but presently is. What else do you want me to say? What are your earliest memories of childhood and growing up there? Well my earliest memories of childhood in Mary Hill were of sheer tenement buildings really, and Glasgow in those days was a rather smoky, dirty place – I thought anyway – 01:30 and one of my earliest memories in Mary Hill is being taken shopping by my mother, and seeing a person on a motorbike knocked down and killed. Mum was very keen to shepherd me away from that, but I had a good look anyway. But we were there for – I suppose – two or three, no four years in all. There were two other siblings born in Mary Hill, and then we shifted to another side of Glasgow, to a place called 02:00 Carntyne where my father had been shifted in the police force, and that’s where I started school at the age of four. What did you think of school? Oh, I thought it was great then, yeah. I recollect being taken by an older girl. -

Chinese-Language Media Outlets

澳大利亚-中国关系研究院 CHINESE-LANGUAGE MEDIA IN AUSTRALIA: Developments, Challenges and Opportunities Professor Wanning Sun Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney FRONT COVER IMAGE: Ming Liang Published by the Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) Level 7, UTS Building 11 81 - 115 Broadway, Ultimo NSW 2007 t: +61 2 9514 8593 f: +61 2 9514 2189 e: [email protected] © The Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) 2016 ISBN 978-0-9942825-6-9 The publication is copyright. Other than for uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without attribution. CONTENTS List of Figures 4 Executive Summary 5 Overview 5 Recommendations 8 Challenges and opportunities 10 Future research 11 Introduction 13 History of Chinese Media in Australia 15 Trends and Recent Developments in the Sector 22 Major Chinese Media (by Sector) 26 Daily paid newspapers 28 Television 28 Radio 28 Online media 29 Access to Major Chinese Media Outlets (by Region) 31 Patterns of Media Consumption 37 The Growth of Social Media Use and WeChat 44 Recommendations for Government, Business and Mainstream Media 49 Challenges and Opportunities 54 Pathways to Future Research 59 References 63 Appendix 67 Appendix A: Circulation Figures (Chinese-language Print Publications in Australia) 67 About ACRI 70 About the Author 71 CHINESE-LANGUAGE MEDIA IN AUSTRALIA 3 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Media sectors currently targeting Chinese migrants in Australia. 21 Figure 2. Time spent with media (hours per week) by Chinese in Australia aged 14-74 years, compared to overall Australian population. 37 Figure 3. -

October 2019 Newsletter

October 2019 newsletter Electoral Regulation Research Network Contents 3 Director’s Message 4 Electoral News 7 Forthcoming Events 8 Event Reports 9 Publications 13 Case Notes Spence v State of Queensland Palmer v Australian Electoral Commission [2019] HCA 24 Setka v Carroll [VSC 571 Yates v Frydenberg De Santis v Staley and Victorian Electoral Commission Director’s Message There is a diversity of electoral systems the workshop, I was struck firstly how, countries where the level of knowledge is worldwide. Each electoral system has despite all these differences, there is low. A critical example here is Australia’s its distinctive peculiarities – Australia a common moral vocabulary when it largest neighbour, Indonesia, with ERRN is no different. It is among a dozen came to understanding and evaluating having held a number of events on or so countries that have an effective elections, much of which loosely comes Indonesian elections. compulsory voting system; its preferential under the rubric of free and fair elections. system is very much unique. The challenges commonly experienced by Second, embrace the unfamiliar. The these two countries were also apparent usual comparator countries are Canada, Such diversity is not necessarily a with three specifically noteworthy: United Kingdom and the United States. problem from the perspective of political participation and representation This focus on the Anglo-Saxon sphere democratic government. As High Court by marginalised communities; ‘fake news’ (which curiously often omits New Justice Dawson recognized in McGinty v and digital campaigning; and money in Zealand) is manifestly narrow. And it is Western Australia, ‘(t)here are hundreds politics.