New Immigrants Improving Productivity in Australian Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inquiry Into Australia's Skilled Migration Program

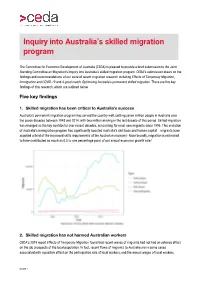

Inquiry into Australia’s skilled migration program The Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) is pleased to provide a brief submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Migration’s Inquiry into Australia’s skilled migration program. CEDA’s submission draws on the findings and recommendations of our suite of recent migration research including Effects of Temporary Migration, Immigration and COVID-19 and A good match: Optimising Australia's permanent skilled migration. There are five key findings of this research, which are outlined below. Five key findings 1. Skilled migration has been critical to Australia’s success Australia’s permanent migration program has served the country well, settling seven million people in Australia over the seven decades between 1945 and 2014, with two million arriving in the last decade of this period. Skilled migration has emerged as the key contributor over recent decades, accounting for most new migrants since 1996. This evolution of Australia’s immigration program has significantly boosted Australia’s skill base and human capital migrants have supplied a third of the increased skills requirements of the Australian economy.i More broadly, migration is estimated to have contributed as much as 0.5 to one percentage point of our annual economic growth rate.ii 2. Skilled migration has not harmed Australian workers CEDA’s 2019 report Effects of Temporary Migration found that recent waves of migrants had not had an adverse effect on the job prospects of the local population. In fact, recent flows of migrants to Australia are in some cases associated with a positive effect on the participation rate of local workers, and the annual wages of local workers. -

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION German Immigrants Took up Land in 1864 In

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION German immigrants took up land in 1864 in the area of Queensland on the Logan River approximately twenty miles south of Brisbane now known as 'Bethania.' They were followed by others and the settlement spread. The area was identified as German for about 100 years. For the historian the questions are: how the Germans came to this area; how they maintained a more or less German identity for so long; and then why that German identity disappeared. 'Bethania' is an anglicization of the name taken by the Lutheran congregation, 'Bethanien,' the German form of the biblical 'Bethany.' In the 1868 Queensland Post Office Directory the name 'Betanien' was applied to the locality occupied by Germans and served by the Logan Reserve post office, but the name did not then come into general usage. 'Bethania' became an official place name from 1885 when the railway station and associated post office were given the name 'Bethania Junction.' The area occupied by the Germans and situated in a bend of the Logan River was referred to as the 'German Pocket,' a somewhat confusing term as there were various German Pockets in Queensland, including one farther down the Logan. For purposes of this thesis it is convenient to refer to the area at all times as 'Bethania.' The area originally settled by the Germans is within the present Bethania, and all the rest of the present Bethania was later taken over by Germans from English and Irish settlers. Germans also acquired land from English and Irish settlers in and around Waterford and farther upstream, and across the river in Loganholme after the land of the cotton plantation was subdivided. -

Migration and Its Effect on Australia

GEOGRAPHY MIGRATION AND ITS EFFECT ON AUSTRALIA Target Group: Year 8 Australian Curriculum Reference: Geography + The reasons for and effects of international migration in Australia (ACHGK058). + Identifying and explaining the main types and patterns of international migration, for example permanent migration, temporary labour migration, student migration, forced migration (including refugees) and family reunion. LESSON SUMMARY This lesson looks at forced migrations to Australia (refugees) and the rise of volunteer organisations that have assisted them. LESSON CONTENT AND METHODOLOGY + Students look at Worksheet 1 (fact sheet: More Than 65 Years of Post-war Migration). + Teacher guides class discussion to develop a list of the significant world events that have resulted in migration to Australia. Teacher identifies that some of these migrants were refugees and explains what being a refugee means, using the following definition as a basis for discussion (text from UNHCR website). The 1951 Refugee Convention relating to the Status of Refugees is the key legal document that defines who is a refugee, their rights and the legal obligations of State parties. The 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees removed geographical and temporal restrictions from the Convention. Accordingly, the term “refugee” applies to any person who: “…owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” + Students research where people came from to Australia as a result of the events described in Worksheet 1, and from the list of events drawn up by the class. -

Australians at War Film Archive James Cruickshank

Australians at War Film Archive James Cruickshank (Jim) - Transcript of interview Date of interview: 3rd October 2003 http://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au/archive/770 Tape 1 00:43 Well, I was baptised Andrew James Cruickshank, born on the 24th of March 1929, in Glasgow, Scotland, where my father at the time was a policeman with the northern division of the Glasgow Police Force. And I was 01:00 born at Mary Hill, which was not then a very salubrious suburb, but presently is. What else do you want me to say? What are your earliest memories of childhood and growing up there? Well my earliest memories of childhood in Mary Hill were of sheer tenement buildings really, and Glasgow in those days was a rather smoky, dirty place – I thought anyway – 01:30 and one of my earliest memories in Mary Hill is being taken shopping by my mother, and seeing a person on a motorbike knocked down and killed. Mum was very keen to shepherd me away from that, but I had a good look anyway. But we were there for – I suppose – two or three, no four years in all. There were two other siblings born in Mary Hill, and then we shifted to another side of Glasgow, to a place called 02:00 Carntyne where my father had been shifted in the police force, and that’s where I started school at the age of four. What did you think of school? Oh, I thought it was great then, yeah. I recollect being taken by an older girl. -

The Social Costs and Benefits of Migration Into Australia

The Social Costs and Benefits of Migration into Australia Editors: Kerry Carrington, Alison McIntosh and Jim Walmsley http://www.une.edu.au/arts/CARSS First released in 2007 ISBN 1 920996 07 9 Copyright © Commonwealth of Australia This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the editors, Centre for Applied Research in Social Sciences. ii SOCIAL COSTS AND BENEFITS OF MIGRATION INTO AUSTRALIA Editors Kerry Carrington, Alison McIntosh and Jim Walmsley Authors Chapter 1: Introduction Kerry Carrington, Alison McIntosh and Jim Walmsley Chapter 2: Settlement Patterns and Experiences Jim Walmsley, Fran Rolley, Raj Rajaratnan and Alison McIntosh Chapter 3: Human Capital Michael Bittman, Jude Brown, Alison McIntosh, Fran Rolley, Raj Rajaratnam and Jim Walmsley Chapter 4: Social Capital Jim Walmsley, Alison McIntosh, Kerry Carrington, Michael Bittman, Fran Rolley and Raj Rajaratnam Chapter 5: Produced and Financial Capital – Product Diversity Jim Walmsley, Alison McIntosh and Raj Rajaratnam Chapter 6: Natural Capital Jim Walmsley, Alison McIntosh and Raj Rajaratnam Chapter 7: Shepparton Kerry Carrington, Neil Marshall and Ron Reavell Chapter 8: Toowoomba Kerry Carrington and Ron Reavell Chapter 9: South Brisbane Kerry Carrington, Neil Marshall and Ron Reavell Chapter 10: Darebin Kerry -

'Lúčnica – Slovak National Folklore Ballet' in Melbourne, 2007

Performing Abroad: ‘Lúčnica – Slovak National Folklore Ballet’ in Melbourne, 2007 Diane Carole Roy A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University 3 August 2011 DECLARATION I, Diane Carole Roy, hereby declare that, except where otherwise acknowledged in the customary manner, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this work is my own, and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other university or institution. ………………………………….. ii DEDICATION Jeseñ na Slovensku Vonku je ticho, všade je šero Vo vnútri hmly vidím priatelských duchov Biele brezy so zlatými vlasmi Okolo ich nôh, zlaté koberec Táto krajina je moja sestra Niekedy rušová, niekedy pokojná Niekedy stará, niekedy mladá Ďakujem jej Di Roy 2003 Autumn in Slovakia Outside is quiet, all around is dim, Yet inside the fog I see friendly ghosts White birches with golden hair Around their feet a golden carpet This country is my sister Sometimes turbulent, sometimes peaceful Sometimes old, sometimes young I thank her iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people, without whom this work could not have been achieved: Dr Stephen Wild, for giving me the freedom to follow my lights, and for his support and friendship; Dr Johanna Rendle-Short, for her encouragement in acquiring knowledge and skills in Conversation Analysis; Dr Jozef Vakoš, who generously accepted me into the Trenčín Singers’ Choir, enabling me to be part of the choral community in Trenčín; my friends in the Trenčín Singers’ Choir, who shared their songs and joy in their traditions, and who showed me why by taking me away from the track trodden by tourists; Dr Hana Urbancová at the Institute of Musicology, and Dr Gabriela Kilánová at the Institute of Ethnology, at the Slovak Academy of Sciences, who generously gave me time, consultation and literature; Ing. -

Market Gardening As a Livelihood Strategy

Market Gardening as a Livelihood Strategy A Case Study of Rural-Urban Migrants in Kapit, Sarawak, Malaysia Sarah Wong Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand 2005 Submitted to Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand in partial fulfilment of the Master of Development Studies (MDS) Abstract This research investigates the role market gardening plays in the livelihood strategies of rural-urban migrants. It contributes to the literature on market gardening, livelihood strategies and migration by positioning market gardening as a highly flexible and adaptable mechanism for managing the rural-urban transition among households with few labour alternatives. Such perspective elevates market gardening from simply being a land use category to being an active instrument in the management of rural-urban migration processes. The expanding urban centre of Kapit, Sarawak, Malaysia is used as a case study of a rapidly expanding small town in a predominantly rural domain. Market gardening emerges as an important source of income for both individuals and households as rural-urban migrants negotiate the transition between farming and urban settlement. Many rural-urban migrants adopt market gardening or associated market selling as their first employment in urban centres. First generation migrants often have low off- farm skills which limit their ability to take on alternative occupations. While a rise in market gardening activity is enabled by a growth in demand for fresh vegetables, in the context of Sarawak it is also heavily influenced by the involvement of the state that actively encourages participation, provides advice to farmers and offers subsidies. The expansion of roads from rural to urban areas also plays an important role in improving market gardeners access to urban markets, as well as their access to material inputs. -

Immigration, Visas and Family Violence

Immigration, visas and family violence The ASPIRE Project conducted research in Tasmania This fact sheet summarises the ASPIRE Project findings and Victoria in 2015-2016 with immigrant and refugee about the impact of immigration policy and visa status women, men, community groups and different service on women’s experiences of family violence. The providers. The project explored issues related to information includes some quotes from women who family violence against immigrant and refugee women participated in the project. There are contact details and their children. For more information visit: on the next page about where to get help for family www.anrows.org.au violence. Immigration to Australia Issues caused by visa status Australia is one of the most culturally diverse Most immigrants to Australia generally start out on countries in the world. Almost half of the Australian temporary visas for a few years before they become population (46%) has a direct family link to the permanent residents or citizens. migration program. Immigration is an important part of Australia’s history, identity and growing economy. The ASPIRE Project found that conditions on temporary visas have serious impacts for the safety of Like all immigrants, the women who participated in immigrant women experiencing family violence. the ASPIRE Project came to Australia through different Temporary visas holders face barriers to getting help avenues and for many reasons including as: because these visas have various conditions that can restrict access to income support, public housing, students or partners of students healthcare, and childcare services. These types of skilled, professional workers services are often essential for the ongoing safety of families looking for better opportunities, including victims of family violence. -

Types of Vegetable Gardens Due to Rapid Development of Industry And

Lecture 6 -Types of Vegetable gardens Due to rapid development of industry and cities various type of vegetable gardens came into existence & these have scope for providing self sufficiency in food .Types of vegetable gardens developed based on the area occupied and mode of disposal of the product. • History of vegetable gardens can be traced back with the development of civilization. • In primitive periods tribes used to grow vegetables for their own consumption mainly for self supporting like in home garden/ kitchen garden • Commercial horticulture started around 19th century when people began moving from rural areas to the cities consequent of industrial revolution. • Vegetable farming started to cater the needs of urban population. Such gardens were located away from the town and cities. Better and quicker transport facilities developed, distance from market was no barrier as long as transport facilities were available. • People selected area, and other conditions suited to cultivate one or two specialized crops. Thus a specialized garden away from market developed called truck garden. • As civilization progressed, science advanced people discovered the techniques of preservation of fruits& vegetables. • Selected vegetables suited to processing were grown near factories such gardens were known as vegetable garden for processing. • With further advancement of science and technology vegetables were started to cultivate out of their normal growing season in protected structures thus gardens for vegetable forcing came up. • With the advancement of population large quantities of vegetables were cultivated in all above type of garden. • Thus seeds were in great demand. Therefore vegetable garden have been developed exclusively for the production of vegetable seeds. -

Dilpreet Sambali

Overcoming cultural shock through accepting a hybrid identity in Australia Dilpreet Sambali I still remember walking out of the airport, when the first gust of cool Australian breeze hit me. I gave out a sigh of relief as I thought about not having to breath Hong Kong’s muggy, humid air for six months. It felt surreal that I was finally here. Only three days before I was still worrying about whether I would receive my visa in time for the first week of the semester. I was oozing with excitement, thinking about the coming six months. I was eager and hopeful. I wanted to make lasting friendships, get out of my comfort zone and try new things. In the coming week, I joined every activity in the orientation week with the hope of meeting new people. While I didn’t mind being alone and traveling by myself, I didn’t want to leave Australia without making new friendships. I was also sure that I didn’t want to stick to other Hong Kong students which is why I didn’t try to find the other two exchange students from CUHK (something I regretted soon). However, I might have been too optimistic. Making friends wasn’t as easy as I had thought. I’m an awkwardly introverted person. I can barely even maintain eye contact while talking. Making friends and socializing certainly is not my strong suit. Being an “innate multicultural” doesn’t make it any easier. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Identity Crisis: the downside of growing up in a multi-cultural environment I am a third generation Punjabi born and raised in Hong Kong. -

Re-Visioning Sydney from the Fringe: Productive Diversities for a 21St Century City

Re-visioning Sydney from the Fringe: Productive Diversities for a 21st Century City Sarah James Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2009 Dedication To my grandparents, whose commitment to social and environmental justice has always inspired me. ii Acknowledgements There are so many people whose assistance and generosity with their time, knowledge and experience was critical to the realisation of this research project. I would like to gratefully acknowledge and thank: All those who participated in this research. In particular I would like to thank the farmers and Aboriginal groups who shared their experiences as well as their valuable time. I would also like to thank the various government representatives, at local and state level, and consultants who provided a broader perspective to my research. My primary supervisor Professor Kay Anderson, for her invaluable guidance, support and eternal patience in the crafting of this thesis. It has been a great privilege to learn from such a brilliant scholar and dedicated teacher. Thank you for believing in my ideas and for encouraging me to strive for ever-higher standards. Other supervisors Professor Ien Ang, whose encouragement and intellectual contributions were key to the development of this thesis. Dr Fiona Allon, for her contributions to the formation and refinement of this thesis. I would also like to express my thanks to: Associate Professor Frances Parker, who generously shared her experience and knowledge from years of work with Sydney’s culturally and linguistically diverse market gardeners. Her long-standing relationships with, and insight into, these groups made possible the principal empirical study on which this research is based The Centre for Cultural Research, which provided a creative and supportive environment for research. -

Hong Kong-Born

Hong Kong-born Victorian Community Profiles: 2016 Census CONTENTS Acknowledgements Notes on the data Tables 1 Distribution within Australia of Hong Kong-born: 2016, 2011 2 Number of Hong Kong-born by Top Twenty Local Government Areas and their Major Suburbs, Victoria: 2016 3 Number of Hong Kong-born by Top Twenty Local Government Areas, Victoria: 2016, 2011 4 Year of Arrival of Hong Kong-born and Total Victorian Overseas-born: 2016 5 Year of Arrival by Top Twenty Local Government Areas, Hong Kong-born, Victoria: 2016 6 Age Groups of Hong Kong-born and the Total Victorian Population: 2016, 2011 7 Total Persons Identified with Chinese Ancestry by Top Twenty Local Government Areas, Victoria: 2016, 2011 8 Country of Birth (Top Twenty plus Australia) of Persons of Chinese Ancestry, Victoria: 2016, 2011 9 Languages Spoken at Home (Top Twenty), Hong Kong-born and the Total Victorian Population: 2016, 2011. 10 Languages Spoken at Home (Top 3) by Top Twenty Local Government Areas, Hong Kong-born, Victoria, 2016 11 Proficiency in Spoken English, Hong Kong-born, Victoria: 2016, 2011 12 Proficiency in Spoken English by Top Twenty Local Government Areas, Hong Kong-born, Victoria: 2016 13 Religious Affiliation (Top Twenty), Hong Kong-born and the Total Victorian Population: 2016, 2011 14 Religious Affiliation (Top Three) by Top Twenty Local Government Areas, Hong Kong-born, Victoria: 2016 15 Type of Internet Connection, Hong Kong-born and the Total Victorian Population: 2016, 2011 16 Type of Internet Connection by Top Ten Local Government Areas, Hong