Lessons from China's Response to COVID-19: Shortcomings, Successes, and Prospects for Reform in China's Regulatory State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Primer on Governance Issues for China and Hong Kong

A Primer on Governance Issues for China and Hong Kong Michael DeGolyer October 2010 marks the 40th anniversary of the establishment of Canadian diplomatic relations with China. In recent years we usually think of China in terms of trade or currency issues or the potential impact of the booming Chinese economy. The political system is ignored as it is thought to be outside the western democratic tradition. This article looks at how modern China is dealing 2010 CanLIIDocs 256 with political forces arising from its increasingly capitalist economic system. It explains the very strong resistance to federalist theory although in some ways China seems headed toward a kind of de facto federalism. It suggests, particularly in the context of China-Hong Kong relations, we may be witnessing a new approach to governance which deserves to be better known among western states as they grapple with their own governance issues and as they try to come to terms with the emergence of China as a world power. entral authorities of the Peoples Republic Despite official denials that China practices any form of China are sensitive to even discussing of federalism, non-China based scholars such as Zheng Cfederalism. Those within China advocating Yongnian1 of the National University of Singapore federalism as a solution to China’s complex ethnic and may and do make the case for federalism in China. He regional relations have more than once run afoul of argues that in truth China governs itself behaviorally official suspicion that federalism is another name for as a de facto federalist state. -

HRWF Human Rights in the World Newsletter Bulgaria Table Of

Table of Contents • EU votes for diplomats to boycott China Winter Olympics over rights abuses • CCP: 100th Anniversary of the party who killed 50 million • The CCP at 100: What next for human rights in EU-China relations? • Missing Tibetan monk was sentenced, sent to prison, family says • China occupies sacred land in Bhutan, threatens India • 900,000 Uyghur children: the saddest victims of genocide • EU suspends efforts to ratify controversial investment deal with China • Sanctions expose EU-China split • Recalling 10 March 1959 and origins of the CCP colonization in Tibet • Tibet: Repression increases before Tibetan Uprising Day • Uyghur Group Defends Detainee Database After Xinjiang Officials Allege ‘Fake Archive’ • Will the EU-China investment agreement survive Parliament’s scrutiny? • Experts demand suspension of EU-China Investment Deal • Sweden is about to deport activist to China—Torture and prison be damned • EU-CHINA: Advocacy for the Uyghur issue • Who are the Uyghurs? Canadian scholars give profound insights • Huawei enables China’s grave human rights violations • It's 'Captive Nations Week' — here's why we should care • EU-China relations under the German presidency: is this “Europe’s moment”? • If EU wants rule of law in China, it must help 'dissident' lawyers • Happening in Europe, too • U.N. experts call call for decisive measures to protect fundamental freedoms in China • EU-China Summit: Europe can, and should hold China to account • China is the world’s greatest threat to religious freedom and other basic human rights -

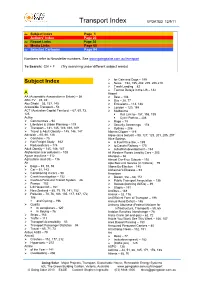

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Ideological Responses to the Coronavirus Pandemic: China and Its Other

IDEOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC: CHINA AND ITS OTHER Samuli Seppänen† Abstract This Article discusses the ongoing coronavirus pandemic as an instance of ideological contestation between the People’s Republic of China and its ideological Other—the “Western” liberal democracies. Much of this ideological contestation highlights the idiosyncratic aspects of opposing ideological narratives. From the illiberal perspective, promoters of liberal narratives on governance and public health can be said to focus too much on procedural legitimacy and, consequently, appear to be ill-placed to acknowledge and respond to public health emergencies. Conversely, from the liberal perspective, advocates of illiberal narratives appear to be responding to a never-ending emergency and, consequently, seem unable to take full advantage of procedural legitimacy and rule-based governance in order to prevent public health emergencies from occurring. The coronavirus pandemic also exposes the aspirational qualities of both ideological narratives. On one hand, it appears aspirational to assume that the coronavirus response in liberal democratic countries can be based on the respect for individual freedom, human dignity, and other liberal first principles. On the other hand, the image of a strong, stable government projected by the CCP also seems to be based on aspirational notions about the coherence and resilience of the P.R.C.’s governance project. In the middle of the pandemic, it appears that the coronavirus follows no ideological script. † Associate Professor, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Law. Published by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, 2020 2020] U. PA. ASIAN L. REV. 25 Abstract ................................................................................... 24 I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 25 II. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

COVID-19 China Mission VPC 09 Feb 2021

COVID-19 China Mission VPC 09 Feb 2021 Speaker key: MF Mi Feng LW Professor Liang Wannian PE Mr Peter Ben Embarek MK Madam Marion Koopmans QU Questioners 00:00:23 MF Ladies and gentlemen, dear friends, good afternoon. Welcome to the press conference of joint expert team of China WHO SARS-CoV-2 origin research. This is Mi Feng, the spokesperson of China National Health Commission. Since COVID-19 became a global pandemic, WHO has been actively promoting the international cooperation in terms of the COVID-19 response. China has always been showing firm support to WHO in terms of unleashing the role of WHO in the leadership of the global COVID-19 response. 00:01:55 With the consensus based on two-sides negotiation, China and WHO have conducted joint research of the SARS-CoV-2 global source-tracing including the China parts since the arrival of international expert teams in Wuhan from January 14, 2021. The joint expert team has been working from three groups, respectively, the group of epidemiology, molecular research, animal and environment. The experts have been working in the forms of video conferences, onsite interviews and visits, and also discussions. They have conducted systematic and full-fledged research. They have already concluded the China part of the source-tracing in Wuhan according to the original plan. During this period, Mr Ma Xiaowei, the minister of China National Health Commission, has been discussing and having abundant communication with Dr Tedros, the Director-General of WHO, through telephone. They have fully exchanged their ideas in terms of the scientific cooperation in the origin source-tracing. -

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao Jiandong CHEN 㱩ڎ暒 School of International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology Sydney Sydney, Australia 2018 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This thesis is the result of a research candidature conducted with another University as part of a collaborative Doctoral degree. Production Note: Signature of Student: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: 30/10/2018 ii Acknowledgements The completion of the thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jingqing Yang for his continuous support during my PhD study. Many thanks for providing me with the opportunity to study at the University of Technology Sydney. His patience, motivation and immense knowledge guided me throughout the time of my research. I cannot imagine having a better supervisor and mentor for my PhD study. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Associate Professor Chongyi Feng and Associate Professor Shirley Chan, for their insightful comments and encouragement; and also for their challenging questions which incited me to widen my research and view things from various perspectives. -

Multidisipliner COVID-19 Editör: Dr

BURSA TAB‹P ODASI SÜREKL‹ TIP E⁄‹T‹M‹ PANDEM‹ K‹TABI TEMMUZ, 2020 Multidisipliner COVID-19 Editör: Dr. Cem Heper Nilüfer Aylin ACET ÖZTÜRK Berna AKOVA Kiper ASLAN Ali AYDINLAR Kenan AYDO⁄AN Gizem AYTO⁄U Naile BOLCA TOPAL Levent BÜYÜKUYSAL Belk›s Nihan COfiKUN Nil Kader ÇA⁄AÇ Ediz DALKILIÇ Gülay DURMUfi ALTUN Baflak ERDEML‹ GÜRSEL Alparslan ERSOY Canan ERSOY Gökhan GÖKALP Asl› GÖREK D‹LEKTAfiLI Özge GÜÇLÜ AYDIN Zülfiye GÜL Rümeysa Ayfle GÜLLÜLÜ Mustafa K. HACIMUSTAFAO⁄LU Yasemin HEPER Hakk› Caner ‹NAN Ferda fi. KAHVEC‹ Cansu KARA TURAN Fikret KASAPO⁄LU Esra KAZAK Sertaç Argun KIVANÇ Ülkü KORKMAZ Selim Giray NAK Ömer Fatih NAS Osman Okan OLCAYSÜ Barbaros ORAL Banu OTLAR CAN Gökhan ÖNGEN Cüneyt ÖZAKIN Alis ÖZÇAKIR Büflra ÖZDEM‹R Vildan ÖZKOCAMAN Rifat ÖZPAR Mine ÖZfiEN Kay›han PALA ‹mran SA⁄LIK Yusuf S‹VR‹O⁄LU P›nar TAfiAR Özlem TAfiKAPILIO⁄LU Alpaslan TÜRKKAN Gürkan UNCU Yeflim UNCU P›nar VURAL Kadir YEfi‹LBA⁄ Emel YILMAZ Aysun YILMAZLAR Pandemide hayatlarını kaybeden meslektaşlarımıza… Bu kitap onlara adanmıştır. KALPLERİMİZDELER… Bursa Tabip Odası Sürekli Tıp Eğitimi PANDEMİ KİTABI Temmuz, 2020 Multidisipliner COVID-19 Editör: Dr. Cem Heper Grafik: Naci Demiray ISBN: 978-605-9665-56-8 Bursa Tabip Odası Yayınları www.bto.org.tr e-mail: [email protected] UYARI ve NOTLAR: Bu kitaptaki bilgiler tıbbın her alanında olduğu gibi sürekli olarak yenilenmekte ve değişmektedir. Kitabın kapsamı nedeniyle aktarılan bilgiler oldukça sınırlı ölçülerdedir. İnsanların her biri, diğerlerine göre farklı özelliklere ve duyarlılıklara sahiptir. Bu nedenle buradaki bilgilerin uygulanmasından ve yeterliliğinden doğacak tıbbi ve hukuki sorumluluklar uygulamayı yapan hekim ve kişilere aittir. -

Coinfection and Other Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 In

Coinfection and Other Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 in Children Qin Wu, MD,a,p Yuhan Xing, MD,b,p Lei Shi, MB,a,p Wenjie Li, MS,a Yang Gao, MS,a Silin Pan, PhD, MD,a Ying Wang, MS,c Wendi Wang, MS,a Quansheng Xing, PhD, MDa BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is abstract a newly identified pathogen that mainly spreads by droplets. Most published studies have been focused on adult patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but data concerning pediatric patients are limited. In this study, we aimed to determine epidemiological characteristics and clinical features of pediatric patients with COVID-19. METHODS: We reviewed and analyzed data on pediatric patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, including basic information, epidemiological history, clinical manifestations, laboratory and radiologic findings, treatment, outcome, and follow-up results. RESULTS: A total of 74 pediatric patients with COVID-19 were included in this study. Of the 68 case patients whose epidemiological data were complete, 65 (65 of 68; 95.59%) were household contacts of adults. Cough (32.43%) and fever (27.03%) were the predominant symptoms of 44 (59.46%) symptomatic patients at onset of the illness. Abnormalities in leukocyte count were found in 23 (31.08%) children, and 10 (13.51%) children presented with abnormal lymphocyte count. Of the 34 (45.95%) patients who had nucleic acid testing results for common respiratory pathogens, 19 (51.35%) showed coinfection with other pathogens other than SARS-CoV-2. Ten (13.51%) children had real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis for fecal specimens, and 8 of them showed prolonged existence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

CONNECTION the Official Newsletter of Zhejiang University Issue 16 Feb.2020

CONNECTION The Official Newsletter of Zhejiang University Issue 16 Feb.2020 COVID-19 Special Issue Stand Strong Message from Editor-in-Chief CONNECTION Welcome to the special COVID-19 issue of Issue 16 CONNECTION, which highlights the efforts and contributions of ZJU community in face of the epidemic. As a group, they are heroes in harm's way, givers and doers who respond swiftly to the need of our city, our country and the world. When you read their stories, you'll recognize the strength and solidarity that define all ZJUers. ZJU community has demonstrated its courage and resilience in the battle against the novel coronavirus. At this time, let us all come together to protect ourselves and our loved ones, keep all those who are at the front lines in our prayers and pass on our gratitude to those who have joined and contributed to the fight against the virus. Together, we will weather this crisis. LI Min, Editor-in-Chief Director, Office of Global Engagement Editorial office : Global Communications Office of Global Engagement, Zhejiang University 866 Yuhangtang Road, Hangzhou, P.R. China 310058 Phone: +86 571 88981259 Fax: +86 571 87951315 Email: [email protected] Edited by : CHEN Weiying, AI Ni Designed by : HUANG Zhaoyi Material from Connection may be reproduced accompanied with appropriate acknowledgement. CONTENTS Faculty One of the heroes in harm’s way: LI Lanjuan 03 ZJU medics answered the call from Wuhan 04 Insights from ZJU experts 05 Alumni Fund for Prevention and Control of Viral Infectious Diseases set up 10 Alumni community mobilized in the battle against COVID-19 11 Education Classes start online during the epidemic 15 What ZJUers feel about online learning 15 Efforts to address concerns, avoid misinformation 17 International World standing with us 18 International students lending a hand against the epidemic 20 What our fans say 21 FacultyFaculty ZJU community has taken on the responsibility to join the concertedZJU community efforts has takenagainst on thethe responsibility spreadto join the of concerted the virus. -

Health Privatisation in China: from the Perspective of Subnational

Health Privatisation in China: from the Perspective of Subnational Governments By FENG Qian Submitted to Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Anil Duman Budapest, Hungary 2020 Abstract From 2009, the Chinese government started to promote the policy She Hui Ban Yi/SHBY that encourages private investment in hospitals. This strategy of promoting private investment in hospitals represents the overall privatisation trend in Chinese health policymaking. Building on the national level health policymaking, the thesis focuses on the subnational governments in China and explains why are this national initiative has been implemented differently at the subnational level. Most existing studies in this topic focus either on the national level policymaking, discussing the relations between welfare policies and regime type or ideologies; or on the efficiency of public versus private hospitals in health sector by evaluating the outcomes. The thesis aims to understand SHBY and privatisation in health mainly from the local governments’ perspective, analysing how the fiscal survival pressure and political incentives affect the actual health policymaking in local governments in China. Drawing on official statistics, government policies and existing studies, the thesis mainly consider two types of influencing factors, and categorises three types of responses at the subnational levels. While the implementation of this policy requires a lot of resources and efforts, the thesis emphasises that, firstly, for the local governments, the fiscal impact, especially the hard budget constraint from the central government and soft budget constraint to the local public sector, plays the key role in health privatisation policies in China.