Images of China: a Comparative Framing Analysis of Australian Current Affairs Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

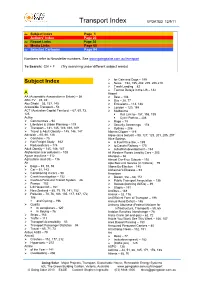

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

“Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4239–4257 1932–8036/20160005 Doing “Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News DEBING FENG1 Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China Unlike print news that is static and mainly composed of written text, television news is dynamic and needs to be delivered with diversified presentational modes and forms. Drawing upon Bakhtin’s heteroglossia and Goffman’s production format of talk, this article examined the presentational forms and strategies deployed in BBC News at Ten and CCTV’s News Simulcast. It showed that the employment of different presentational elements and forms in the two programs reflects two contrasting types of news discourse. The discourse of BBC News tends to present different, and even confrontational, voices with diversified presentational forms, such as direct mode of address and “fresh talk,” thus likely to accentuate the authenticity of the news. The other type of discourse (i.e., CCTV News) seems to prefer monologic news presentation and prioritize studio-based, scripted news reading, such as on-camera address or voice- overs, and it thus creates a single authoritative voice that is likely to undermine the truth of the news. Keywords: authenticity, mode of address, presentational elements, voice, television news The discourse of television news has been widely studied within the linguistic world. Early in the 1970s, researchers in the field of critical linguistics (CL; e.g., Fowler, 1991; Fowler, Hodge, Kress, & Trew, 1979; Hodge & Kress, 1993) paid great attention to the ideological meaning of news by drawing upon a kit of linguistic tools such as modality, transitivity, and transformation. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

Puzzled Eureka Street Cryptic Crossword No

s\) ~ ~ b:c i~ ug h e,\J i z a~r\AJevr 1) Th e Kakapo parrot is found in New Zea land. 2) Lichenostomus melanop s, or Yellow tufted honeyeater. NB: Victoria's official bird emblem is th e helmeted honeyeater, Lichenostomus melanops cassidix. 20) Bru ce Armstrong is better know for his huge 'chainsaw' sculp 3) Dog Monday. tures of animals, such as his huge eaglehawk Bunjil w hi ch over 4) M ari anne Faithful!. looks th e Docklands, M elbourn e. 5) Bridge (th e World Tea m O lympiad). 21) The Golden Sec tion . 6) (i) M ichae l and Patrick Ca nn y. 22) (i) Th e remains are those of Lord Nelson (1758-1805); (ii ) Michae l Ca nny. (ii ) th e ca rdinal was Ca rdinal Wolsey (1473 - 1530); and (iii) 19 (M ichae l) and 22 (Patri ck). (iii) th e artist was Giovann i da M aian o. (iv) John Hines was shot and kil led. 23) Edouard M anet (1832-83) and th e offe nding pain ting was hi s 7) Lazza ro Spallanza ni, in Italy 1765. reclining nude fi gure O lympia (1863). 8) 250 mil es or around 402.33 600 kilometres . 24) If 1+2+ ... +2 n is prime, th en 2n (1+2+ ... +2 n) is perfect. The 9) (i) M onaco-population per sq km- 16,35 0. quote is from Euclid's Elements, IX.36, 300BC (ex tra poin t) . (ii) Mongoli a-population per sq km- 1.8. 25) Robert Record e (c. -

Proud to Be Union

Proud to be Union SUBMISSION Joint Standing Committee on Treaties Examination of the Free Trade Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the People's Republic of China THE ELECTRICAL DIVSION of the Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia Suite 408, Level 4, 30-40 Harcourt Parade, Rosebery NSW 2018 I Ph: (02) 9663 3699 I Fax: (02) 9663 5599 Proud to be Union Executive Summary The Electrical Trades Union (ETU) is the Electrical, Energy and Services Division of the Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia (CEPU). The ETU represents approximately 65,000 workers electrical and electronics workers around the country and the CEPU as a whole represents approximately 100,000 workers nationally, making us one of the largest trade unions in Australia. The ETU welcomes the opportunity to submit to the Committee in relation to its examination of the Free Trade Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the People's Republic of China (ChAFTA). The role of the Committee (Appendix 1) is to assess the ChAFTA and form a view as whether it is in Australia’s national interest. We submit that the provisions around labour mobility, training, worker protections (or lack there-of), corporate rights and more, mean the agreement cannot be supported by the Committee in its current form. The ChAFTA will lock Australians out of job opportunities, erode industrial and public safety standards, and expose Australia to unfunded legal action that costs millions. Earlier this year the Productivity Commission voiced significant concerns over Free Trade Agreements1 and, like unions, continue to argue that these agreements don’t deliver measurable economy wide benefits as claimed, impose significant costs, and are oversold by governments. -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Dinner” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 6, folder “3/25/76 - Radio and Television Correspondents' Dinner” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON March 19, 1976 MEMORANDUM TO: RED CAVANEY P~ER SORUM FROM: S AN PORTER . SUBJECT: Mrs; Ford Attendance at the Radio and TV Correspondent's Dinner (Fay Wells), Washington Hilton Hotel, March 26th Mrs. Ford will attend the Radio and TV Correspondent's Dinner as a guest of Fay Wells of Storer Broadcasting Company. Mrs. Ford has attended this dinner as Fay's guest for many years and has been very fond of Fay through the years . She will travel to the dinner with the President (the cocktail period is 6:30-8:00 in the Georgetown Suite). Mrs. Ford then will break from the President and will join Fay and her guests in the Jefferson Room for dinner (I understand the President will be eating in the Ballroom) . -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

Zidane in Tartarus

Zidane in Tartarus: A Neoaristotelian Inquiry into the Emotional Dimension of Kathartic Recognition © Stephanie Alice Baker Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2010 Copyright Stephanie Alice Baker 2010 For Richard Stephen Baker & Andrea Gale Baker Acknowledgements There are numerous people to whom I owe gratitude for the completion of this thesis: Firstly, the faculty at the University of Sydney, who nourished my passion for the classics and subsequently sociology. I am particularly grateful for the scholarship encouraging me to pursue a PhD and the generous funding provided to conduct fieldwork, archival research and to present at international conferences during the initial two years of my dissertation. The University of Western Sydney must also be thanked for the scholarship and funding opportunities offered during the final year and a half of my dissertation. I would also like to thank the University of Chicago, and more specifically Hans Joas and the staff at Regenstein Library, for their hospitality and allowing me to access the unpublished manuscripts of George Herbert Mead in 2006. Special thanks must also be made to the University of Leicester for hosting me as a Visiting Fellow from 2007-8, a fellowship that was to shape the direction of my dissertation in innumerable ways, and Patrick Mignon for inviting me to participate in a series of seminars at l'École des hautes études en sciences sociales during the academic year of 2007-8 in Paris. I owe special thanks to my parents, Richard Stephen Baker and Andrea Gale Baker, who have continuously encouraged my educational pursuits, Joanne Finkelstein for her ongoing mentorship during my tertiary education, innumerable friends for their affections and my partner, Adam Peckman, whose unconditional love and support throughout this process will be eternally remembered. -

Meeting of Television Professionals to Promote Dialogue and to Encourage Cooperative Action on the Middle East

MEETING OF TELEVISION PROFESSIONALS TO PROMOTE DIALOGUE AND TO ENCOURAGE COOPERATIVE ACTION ON THE MIDDLE EAST Report of a conference organized by Search for Common Ground with support from the Hollings Center in Istanbul, Turkey February 3-5, 2006 “We as journalists are part of this conflict. We try not to be…. We try for objectivity, but I don’t think we’ve been successful.” – Correspondent for Arab Satellite Station “The problem we have before us is not language or reporting; it is the problem of conflicting narratives… We don’t listen to each other; we don’t absorb each other’s story…. We have to meet somewhere on the road and strike a compromise.” – Israeli Anchor “This is a problem of a dialogue between two deaf people.” – Palestinian Independent TV Executive “It’s very important that tomorrow I will have friends from Palestinian TV and the Gulf. We are all doing the same news daily.” – Israeli Television Executive BACKGROUND The media's traditional approach to controversial and sensitive issues is to explore the extent and range of disagreement, but this rarely results in common understanding or provides a solution to a problem. In fact, the media often seems to exploit a contentious issue for its entertainment value, sometimes leaving readers and audiences with the impression that nothing positive can be achieved and that the extremes of opinion being presented are representative of the majority. In contrast, Common Ground methodologies encourage the exploration of possible areas of agreement between opposing sides of a discussion, try actively to subvert prejudices and stereotyping, to promote the dignity of all sides, and to encourage a positive vision. -

UNAA Media Peace Awards Winners and Finalists

UNAA Media Peace Awards WINNERs and FINALISTs 2016_____________________________________________ Print WINNER Paul Farrell, Nick Evershed, Helen Davidson, Ben Doherty, David Marr and Will Woodward, Guardian Australia, The Nauru Files FINALIST Ben Doherty, Guardian Australia, Lives in Limbo FINALIST SBS, Something Terrible Has Happened to Levai FINALIST Adam Morton, The Age, The Vanishing Island TV – News/Current Affairs WINNER SBS World News, Syria, Five Years of Crisis FINALIST Phil Goyen and Michael Usher, 60 Minutes, Divided States of America FINALIST Jane Bardon, ABC News and Current Affairs, Australia’s Third World Indigenous Housing Shame FINALIST Waleed Aly and Tom Whitty, The Project, ISIL is Weak TV – Documentary WINNER Caro Meldrum-Hanna, Mary Fallon, Elise Worthington, Four Corners, Australia’s Shame FINALIST Brett Mason, Calliste Weitenberg, Bernadine Lim, Jonathan Challis, Micah McGown, Dateline, Allow Me to Die FINALIST Patrick Abboud, Breaking Point, Bullying’s Deadly Toll Radio – News WINNER Jane Bardon, ABC News, Indigenous Residents FINALIST Sue Lannin, ABC Radio National, East Timor Hitlist Radio – Documentary WINNER Christine El-Khoury, ABC News and Current Affairs, Anti-Muslim extremists: How far will they go? FINALIST Dan Box and Eric George, The Australian, Bowraville FINALIST Kristina Kukolja and Lindsey Arkley, SBS, Unwanted Australians FINALIST Jo Chandler, Wendy Carlisle, Tim Roxburgh, Linda McGinnes, ABC Radio National, Ebola with wings: The TB crisis on our doorstep Photojournalism WINNER Darrian Traynor, Gaza’s -

Tweed Shire Echo

THE TWEED what s www.tweedecho.com.au Volume 3 #35 new? Thursday, May 12, 2011 Advertising and news enquiries: Phone: (02) 6672 2280 [email protected] [email protected] CAB Page 12 21,000 copies every week AUDIT LOCAL & INDEPENDENT Tweed goes to P’ville shopping the dogs for the RSPCA centre plan goes off the boil Luis Feliu on the site and use the land for more housing. A shopping complex which residents Pottsville Residents Association from Pottsville and its booming Sea- president Chris Cherry this week told breeze housing estate had expected to Th e Echo that ‘the small-scale super- be built appears to be off the drawing market proposal is no more’. board altogether. ‘As Metricon could not get their Developer of Seabreeze, Metricon, full-line centre approved, they have recently backed off plans for even a now gone ahead with a residential small-scale supermarket on land it rezoning of this area and the blocks owns despite a lengthy and expensive are on sale or already sold,’ Ms Cherry battle to have a larger, full-line one said. approved there. Th e Queensland-based developer, ‘A major fl aw’ Kate McIntosh Bonnie and Sandy Oswald, Benny and Jeanette Whiteley and Fudge, Tori which has several major housing ‘As far as I am concerned this with- and Harvey Bishop are all looking forward to this Sunday’s Million Paws developments underway around drawal of promised local services to Tweed residents and their four-legged Walk for the RSPCA. Photo Jeff ‘Houndog’ Dawson Tweed Shire, now wants to use the residents who have bought in accord- friends will be pounding the pavement land for more housing. -

When Old Meets New: Some Perspectives on Recent Chinese Legal Developments and Their Relevance to the United States (The Importance of Labor Law)

SMU Law Review Volume 64 Issue 4 Article 7 2011 When Old Meets New: Some Perspectives on Recent Chinese Legal Developments and Their Relevance to the United States (The Importance of Labor Law) Louise Willans Floyd Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Louise Willans Floyd, When Old Meets New: Some Perspectives on Recent Chinese Legal Developments and Their Relevance to the United States (The Importance of Labor Law), 64 SMU L. REV. 1209 (2011) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol64/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. WHEN OLD MEETS NEW: SOME PERSPECTIVES ON RECENT CHINESE LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS AND THEIR RELEVANCE TO THE UNITED STATES (THE IMPORTANCE OF LABOR LAW) Dr. Louise Willans Floyd* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 1211 II. THE "DEVELOPING" LAW IN CHINA ................ 1215 A. AN OUTLINE OF "THE NEW LAW" .. .................... 1215 B. BUT THE IDEA OF LAW Is NOT NEW-WHY AN APPRECIATION OF TRADITIONAL CHINESE LAW, CULTURE, AND ENFORCEMENT BARRIERS ARE CRITICAL TO UNDERSTANDING CHINA AND CHINESE LAW TODAY .......................................... 1218 III. PROBLEMS WITH ENFORCING LABOR LAW IN CHINA AND WHY THE WEST, INCLUDING THE UNITED STATES, SHOULD CARE .................... 1221 A. UNION GROWTH-BUT STATE CONTROL OF UNIONS.. 1221 B. CULTURAL BARRIERS TO ENFORCEMENT AND DIFFICULTIES WITH RESEARCHING THEM .............. 1222 C. PROBLEMS WITH RURAL WORKERS, REGIONAL MIGRANT WORKERS, AND THE HUKOU SYSTEM ......