By Duncan Hewitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

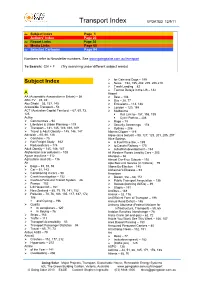

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Chinese Popular Romance in Greater East Asia, 1937-1945 Chun-Yu Lu Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2016 Make Love and War: Chinese Popular Romance in Greater East Asia, 1937-1945 Chun-Yu Lu Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian Studies Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Lu, Chun-Yu, "Make Love and War: Chinese Popular Romance in Greater East Asia, 1937-1945" (2016). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 800. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/800 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures Committee on Comparative Literature Dissertation Examination Committee: Lingchei Letty Chen, Chair Robert E Hegel, Co-Chair Rebecca Copeland Diane Lewis Zhao Ma Marvin Marcus Make Love and War: Chinese Popular Romance in “Greater East Asia,” 1937-1945 by Chun-yu Lu A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2016 St. Louis, Missouri © 2016, Chun-yu Lu Table of Content Acknowledgments ................................................................................................. -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

UNAA Media Peace Awards Winners and Finalists

UNAA Media Peace Awards WINNERs and FINALISTs 2016_____________________________________________ Print WINNER Paul Farrell, Nick Evershed, Helen Davidson, Ben Doherty, David Marr and Will Woodward, Guardian Australia, The Nauru Files FINALIST Ben Doherty, Guardian Australia, Lives in Limbo FINALIST SBS, Something Terrible Has Happened to Levai FINALIST Adam Morton, The Age, The Vanishing Island TV – News/Current Affairs WINNER SBS World News, Syria, Five Years of Crisis FINALIST Phil Goyen and Michael Usher, 60 Minutes, Divided States of America FINALIST Jane Bardon, ABC News and Current Affairs, Australia’s Third World Indigenous Housing Shame FINALIST Waleed Aly and Tom Whitty, The Project, ISIL is Weak TV – Documentary WINNER Caro Meldrum-Hanna, Mary Fallon, Elise Worthington, Four Corners, Australia’s Shame FINALIST Brett Mason, Calliste Weitenberg, Bernadine Lim, Jonathan Challis, Micah McGown, Dateline, Allow Me to Die FINALIST Patrick Abboud, Breaking Point, Bullying’s Deadly Toll Radio – News WINNER Jane Bardon, ABC News, Indigenous Residents FINALIST Sue Lannin, ABC Radio National, East Timor Hitlist Radio – Documentary WINNER Christine El-Khoury, ABC News and Current Affairs, Anti-Muslim extremists: How far will they go? FINALIST Dan Box and Eric George, The Australian, Bowraville FINALIST Kristina Kukolja and Lindsey Arkley, SBS, Unwanted Australians FINALIST Jo Chandler, Wendy Carlisle, Tim Roxburgh, Linda McGinnes, ABC Radio National, Ebola with wings: The TB crisis on our doorstep Photojournalism WINNER Darrian Traynor, Gaza’s -

When Old Meets New: Some Perspectives on Recent Chinese Legal Developments and Their Relevance to the United States (The Importance of Labor Law)

SMU Law Review Volume 64 Issue 4 Article 7 2011 When Old Meets New: Some Perspectives on Recent Chinese Legal Developments and Their Relevance to the United States (The Importance of Labor Law) Louise Willans Floyd Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Louise Willans Floyd, When Old Meets New: Some Perspectives on Recent Chinese Legal Developments and Their Relevance to the United States (The Importance of Labor Law), 64 SMU L. REV. 1209 (2011) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol64/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. WHEN OLD MEETS NEW: SOME PERSPECTIVES ON RECENT CHINESE LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS AND THEIR RELEVANCE TO THE UNITED STATES (THE IMPORTANCE OF LABOR LAW) Dr. Louise Willans Floyd* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 1211 II. THE "DEVELOPING" LAW IN CHINA ................ 1215 A. AN OUTLINE OF "THE NEW LAW" .. .................... 1215 B. BUT THE IDEA OF LAW Is NOT NEW-WHY AN APPRECIATION OF TRADITIONAL CHINESE LAW, CULTURE, AND ENFORCEMENT BARRIERS ARE CRITICAL TO UNDERSTANDING CHINA AND CHINESE LAW TODAY .......................................... 1218 III. PROBLEMS WITH ENFORCING LABOR LAW IN CHINA AND WHY THE WEST, INCLUDING THE UNITED STATES, SHOULD CARE .................... 1221 A. UNION GROWTH-BUT STATE CONTROL OF UNIONS.. 1221 B. CULTURAL BARRIERS TO ENFORCEMENT AND DIFFICULTIES WITH RESEARCHING THEM .............. 1222 C. PROBLEMS WITH RURAL WORKERS, REGIONAL MIGRANT WORKERS, AND THE HUKOU SYSTEM ...... -

New Foreign Policy Actors in China

Stockholm InternatIonal Peace reSearch InStItute SIPrI Policy Paper new ForeIgn PolIcy new Foreign Policy actors in china 26 actorS In chIna September 2010 The dynamic transformation of Chinese society that has paralleled linda jakobson and dean knox changes in the international environment has had a direct impact on both the making and shaping of Chinese foreign policy. To understand the complex nature of these changes is of utmost importance to the international community in seeking China’s engagement and cooperation. Although much about China’s foreign policy decision making remains obscure, this Policy Paper make clear that it is possible to identify the interest groups vying for a voice in policy formulation and to explore their policy preferences. Uniquely informed by the authors’ access to individuals across the full range of Chinese foreign policy actors, this Policy Paper reveals a number of emergent trends, chief among them the changing face of China’s official decision-making apparatus and the direction that actors on the margins would like to see Chinese foreign policy take. linda Jakobson (Finland) is Director of the SIPRI China and Global Security Programme. She has lived and worked in China for over 15 years and is fluent in Chinese. She has written six books about China and has published extensively on China’s foreign policy, the Taiwan Strait, China’s energy security, and China’s policies on climate change and science and technology. Prior to joining SIPRI in 2009, Jakobson worked for 10 years for the Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA), most recently as director of its China Programme. -

Marriage Practice of the Chinese Communist Party in Modern Era, 1910S-1950S

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-23-2011 12:00 AM From Marriage Revolution to Revolutionary Marriage: Marriage Practice of the Chinese Communist Party in Modern Era, 1910s-1950s Wei Xu The University of Western Ontario Supervisor James Flath The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Wei Xu 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, History of Gender Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Xu, Wei, "From Marriage Revolution to Revolutionary Marriage: Marriage Practice of the Chinese Communist Party in Modern Era, 1910s-1950s" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 232. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/232 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM MARRIAGE REVOLUTION TO REVOLUTIONARY MARRIAGE: MARRIAGE PRACTICE OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY IN MODERN ERA 1910s-1950s (Spine -

Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China

Trim: 6.125in 9.25in Top: 0.5in Gutter: 0.875in × CUUS1796-FM CUUS1796/Stockmann ISBN: 978 1 107 01844 0 August 27, 2012 20:24 Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China In most liberal democracies, commercialized media is taken for granted, but in many authoritarian regimes, the introduction of market forces in the media represents a radical break from the past, with uncer- tain political and social implications. In Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China,DanielaStockmannarguesthatthecon- sequences of media marketization depend on the institutional design of the state. In one-party regimes such as China, market-based media promote regime stability rather than destabilizing authoritarianism or bringing about democracy. By analyzing the Chinese media, Stockmann ties trends of market liberalism in China to other authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the post- Soviet region. Drawing on in-depth interviews with Chinese journalists and propaganda officials as well as more than 2,000 newspaper articles, experiments, and public opinion data sets, this book links censorship among journalists with patterns of media consumption and media’s effects on public opinion. Daniela Stockmann is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Leiden University. Her research on political communication and public opin- ion in China has been published in Comparative Political Studies, Political Communication, The China Quarterly,andtheChinese Jour- nal of Communication,amongothers.Her2006 conference paper on the Chinese media and public opinion received an award in Political Communication from the American Political Science Association. i Trim: 6.125in 9.25in Top: 0.5in Gutter: 0.875in × CUUS1796-FM CUUS1796/Stockmann ISBN: 978 1 107 01844 0 August 27, 2012 20:24 ii Trim: 6.125in 9.25in Top: 0.5in Gutter: 0.875in × CUUS1796-FM CUUS1796/Stockmann ISBN: 978 1 107 01844 0 August 27, 2012 20:24 Communication, Society, and Politics Editors W. -

The Challenges of China's Growth

The Challenges of China’s Growth THE HENRY WENDT LECTURE SERIES The Henry Wendt Lecture is delivered annually at the American Enterprise Institute by a scholar who has made major contributions to our understanding of the modern phenomenon of globalization and its consequences for social welfare, government policy, and the expansion of liberal political institutions. The lecture series is part of AEI’s Wendt Program in Global Political Economy, estab- lished through the generosity of the SmithKline Beecham pharma- ceutical company (now GlaxoSmithKline) and Mr. Henry Wendt, former chairman and chief executive officer of SmithKline Beecham and trustee emeritus of AEI. GROWTH AND INTERACTION IN THE WORLD ECONOMY: THE ROOTS OF MODERNITY Angus Maddison, 2001 IN DEFENSE OF EMPIRES Deepak Lal, 2002 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF WORLD MASS MIGRATION: COMPARING TWO GLOBAL CENTURIES Jeffrey G. Williamson, 2004 GLOBAL POPULATION AGING AND ITS ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES Ronald Lee, 2005 THE CHALLENGES OF CHINA’S GROWTH Dwight H. Perkins, 2006 The Challenges of China’s Growth Dwight H. Perkins The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perkins, Dwight H. (Dwight Heald), 1934- The challenges of China’s growth / by Dwight H. Perkins. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. -

New Readings of Lu Xun

Review Essay China perspectives New Readings of Lu Xun: Critic of modernity and re-inventor of heterodoxy SEBASTIAN VEG ore than any other modern writer, Lu Xun remains at the heart of belled a communist writer, the first alternative readings of Lu Xun, building intellectual discussions in China today. There are several reasons on annotations and biographical writings by contemporaries such as Mfor this. One is that no sooner had Lu Xun breathed his last breath Cao Juren 曹聚仁 , who came to Hong Kong in 1950, began to emerge in than the Chinese Communist Party began to build him into its own narrative Western academia in the 1960s. The Hsia brothers, in particular T. A. Hsia’s of national revival, structured around the interpenetration of revolution and 夏濟安 seminal The Gate of Darkness , first published in 1968, played a major nationalism. Lu Xun’s biography, which spanned the crucial juncture from role in unearthing the aestheticism in Lu Xun’s works such as Wild Grass , late-imperial reformist gentry to nationalist revolution, the New Culture, as did the writing of Belgian sinologist Pierre Ryckmans (pen name Simon and finally to the rise of communism as a response to many of the problems Leys). Leo Ou-fan Lee’s 李歐梵 edited volume Lu Xun and his Legacy (1985) that had prevented China’s full transformation into a modern democracy, and his authoritative study Voices from the Iron House (1987) represent a began to serve as an explanatory model for the entire historical evolution culmination of scholarship undertaken in this perspective, in which psycho - of the first half of the twentieth century. -

Communications and China's National Integration: an Analysis of People's

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY •• AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 5 - 1986 {76) COMMUNICATIONS AND CHINA'S NATIONAL INTEGRATION: AN , ANALYSIS OF PEOPLE'S DAILY •I AND CENTRAL DAILY NEWS ON • THE CHINA REUNIFICATION ISSUE Shuhua Chang SclloolofLAw UNivERsiTy of 0 c:.•• MARylANd_. 0 ' Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Acting Managing Editor: Shaiw-chei Chuang Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas.