Robobraille – Automated Braille Translation by Means of an E-Mail Robot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louis Braille

Louis Braille Louis Braille (/breɪl/ ( listen); French: [lwi bʁaj]; 4 January 1809 – 6 January 1852) was a French educator and inventor of a system of reading and writing for use by the blind or visually impaired. His system remains virtually unchanged to this day, and is known worldwide simply as braille. Louis Braille Bust of Louis Braille by Étienne Leroux at the Bibliothèque nationale de France Born 4 January 1809 Coupvray, France Died 6 January 1852 (aged 43) Paris, France Resting place Panthéon, Paris and Coupvray Occupation Educator • inventor Known for Braille Parent(s) Monique and Simon-René Braille Braille was blinded at the age of three in one eye as a result of an accident with a stitching awl in his father's harness making shop. Consequently, an infection set in and spread to both eyes, resulting in total blindness.[1] At that time there were not many resources in place for the blind but nevertheless, he excelled in his education and received a scholarship to France's Royal Institute for Blind Youth. While still a student there, he began developing a system of tactile code that could allow blind people to read and write quickly and efficiently. Inspired by the military cryptography of Charles Barbier, Braille constructed a new method built specifically for the needs of the blind. He presented his work to his peers for the first time in 1824. In adulthood, Louis Braille served as a professor at the Institute and had an avocation as a musician, but he largely spent the remainder of his life refining and extending his system. -

TO IMPLEMENT UNIVERSAL DESIGN for LEARNING a Working Paper from the Global Reading Network for Enhancing Skills Acquisition for Students with Disabilities

USING INFORMATION COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGIES TO IMPLEMENT UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR LEARNING A working paper from the Global Reading Network for enhancing skills acquisition for students with disabilities Authors David Banes, Access and Inclusion Services Anne Hayes, Inclusive Development Partners Christopher Kurz, Rochester Institute of Technology Raja Kushalnagar, Gallaudet University With support from Ann Turnbull, Jennifer Bowser Gerst, Josh Josa, Amy Pallangyo, and Rebecca Rhodes This paper was made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The paper was prepared for USAID’s Building Evidence and Supporting Innovation to Improve Primary Grade Reading Assistance for the Office of Education (E3/ED), University Research Co., LLC, Contract No. AID-OAA-M-14-00001, MOBIS#: GS-10F-0182T. August 2020 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Unless otherwise noted, Using Information Communications Technologies to Implement Universal Design for Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Under this license, users are free to share and adapt this material in any medium or format under the following conditions. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. Attribution: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the licensed material, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. A suggested citation appears at the bottom of this page, and please also include this note: This document was developed by “Reading Within Reach,” through the support of the U.S. -

Val Av Datoranpassningar För Elever Som Läser Och Skriver Punktskrift

Att skriva utan att kunna se Val av datoranpassningar för elever som läser och skriver punktskrift Ann Ekelius Örnblom Specialpedagogiska institutionen Självständigt arbete 15 hp Specialpedagogik Magisterkurs med ämnesbredd, inriktning synpedagogik och synnedsättning, 75 hp Höstterminen 2008 Examinator: Örjan Bäckman Att skriva utan att kunna se Val av datoranpassningar för elever som läser och skriver punktskrift Ann Ekelius Örnblom Sammanfattning Ekelius Örnblom, A. (2008). Att skriva utan att kunna se. Val av datoranpassningar för elever som läser och skriver punktskrift. Självständigt arbete i Specialpedagogik inom Magisterkurs med ämnesbredd, inriktning synpedagogik och synnedsättning. Stockholms Universitet. Specialpedagogiska institutionen. Syftet med studien var att få en översikt över vilken datorutrustning elever som läser och skriver punktskrift har i förskoleklass, skolår 1, 5 och 6 höstterminen 2008. Syftet var också att se vilka som samverkar inför förskrivning av ny utrustning och vilka faktorer som påverkade valet. Studien bygger på telefonintervjuer med nio synpedagoger som har förskrivit utrustning till elever i förskoleklass och år 1 och nio pedagoger i skolan som arbetar med en elev med grav synskada som läser och skriver punktskrift i skolår 5 och 6. Det finns inte någon nationell standard på utrustning till elev med grav synskada för arbete med punktskrift vid datorn. Följden är att det finns många olika produkter hos eleverna. Flera som arbetar med eleverna, inom landsting, kommun och stat, hade uppskattat om det fanns en rekommendation på nybörjarutrustning. Vikten av samverkan i dessa diskussioner om utrustning och metodik blir tydlig och många anser att strukturen för hur samverkan fungerar är oerhört viktig för elevens skolgång. Samtliga respondenter tycker att man skall jobba med punktskriftstangentbord under tiden man lär sig läsa och skriva och samtliga elever i de yngre åldrarna har fått datoranpassning med punktskriftstangentbord. -

|||GET||| Representing Emotions 1St Edition

REPRESENTING EMOTIONS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Helen Hills | 9781351904162 | | | | | Children's Books That Teach Kids About Emotions Subject Representing Emotions 1st edition credit approval. Candlewick Press. Only Feelings ". Main article: Emoticons Unicode block. Accessible publishing Braille literacy RoboBraille. This alphabet book guides kids through 26 different emotions and encourages them to think about their own feelings. First editions from Sheed and Ward US have no additional printings listed on the Representing Emotions 1st edition page. Very minimal damage to the cover including scuff marks, but no holes or tears. The sound is intended to communicate an emotional subtext. The first-edition statement was occasionally left out in subsequent printings, but the presence of later-published titles within the book may help to identify it as a later edition. Each publisher has a different method of designating firsts and they change it regularly, too. InDespair, Inc. Opens image gallery Image not available Photos not available for this variation. This story of a girl experiencing intense feelings offers a road map for coping with anger. Korean style contains Korean jamo letters instead of other characters. InRussian entrepreneur Oleg Teterin claimed to have been granted the trademark on the ;- emoticon. First editions from Pantheon Books, untilhave no additional printings indicated on the copyright page. This is the latest accepted revisionreviewed on 18 October Standard works have no indication of printings within an edition: all printings of the first edition carry the same identification; only second printings with changed or added material are indicated. Binding has minimal wear. Keep scrolling for a selection of books that promote emotional intelligence. -

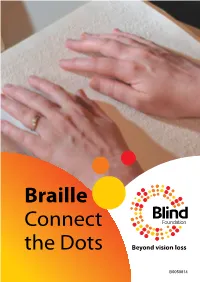

Braille Connect the Dots

Braille Connect the Dots B0050814 2 Contents 4 What is braille? 5 How braille began 6 The alphabet 8 Numbers 9 Capitals, punctuation and spacing 11 Common phrases 12 Contracted braille 13 Getting more technical 15 Writing braille 19 Using braille 23 Braille opens doors 24 W here do I go to learn more about braille? 25 Ho w can I get documents made into braille? 27 Important contacts and links 28 Summar y of alphabet and numbers 3 What is braille? Braille is the reading and writing system used by blind people all over the world. It is bumps or dots that blind people read with their fingers. As well as braille books, there are braille menus, recipes, board games and playing cards. You can even find braille on some packaging, ATM machines, lift buttons and other signs. In this booklet, we’re going to teach you some braille basics. There are activities and some great links so you can get more information. 4 How braille began Braille was invented by a French boy in 1824. His name was Louis Braille. Here’s some of his story. Louis Braille was born in 1809. He became blind due to an accident at the age of three, and later attended the first school for the blind in Paris from 1819. He was taught to read raised, enlarged print but found it very slow. Also, no one had yet found a way to enable blind people to write. Louis began to look for better ways of reading and writing for blind people. -

Zero Project Almanac 2013–2016

Zero Project Almanac 2013–2016 Supporting the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities UN CRPD Ratifcation World Map Countries by year of ratifcation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilties, 2007 to 2016 (total: 172 by end of 2016) Year of Ratifcation 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Countries that have NOT ratifed UN CRPD (another 12 countries, among them the United States and Ireland, have signed the UN CRPD but not ratifed it) “For all persons with disabilities and for all contributors to the Zero Project, worldwide” Zero Project Director and Zero Project Almanac coordinator: Michael Fembek Design: Christoph Almasy Articles about Innovative Practices and Policies: Zach Dorfman Article about the Essl Foundation: Saskia Wallner Graphic Facilitation: Petra Plicka Portrait Illustrations: Alexander Fuehrer Easy Language Text: Atempo GmbH Editing: John Tessitore Photos of Zero Project Conferences: Frank Garzarolli, Pepo Schuster; Austrian Conferences: Fotos provided by regional Conference partner Photos of all organizations mentioned have been provided by these organizations ISBN 978-3-9504208-2-1 © Essl Foundation, January 2017. All rights reserved. First published 2017. Printed in Austria. Disclaimers The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily refect the views of the Essl Foundation or the Zero Project. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Essl Foundation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

OSINT Handbook September 2020

OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 Aleksandra Bielska Noa Rebecca Kurz, Yves Baumgartner, Vytenis Benetis 2 Foreword I am delighted to share with you the 2020 edition of the OSINT Tools and Resources Handbook. Once again, the Handbook has been revised and updated to reflect the evolution of this discipline, and the many strategic, operational and technical challenges OSINT practitioners have to grapple with. Given the speed of change on the web, some might question the wisdom of pulling together such a resource. What’s wrong with the Top 10 tools, or the Top 100? There are only so many resources one can bookmark after all. Such arguments are not without merit. My fear, however, is that they are also shortsighted. I offer four reasons why. To begin, a shortlist betrays the widening spectrum of OSINT practice. Whereas OSINT was once the preserve of analysts working in national security, it now embraces a growing class of professionals in fields as diverse as journalism, cybersecurity, investment research, crisis management and human rights. A limited toolkit can never satisfy all of these constituencies. Second, a good OSINT practitioner is someone who is comfortable working with different tools, sources and collection strategies. The temptation toward narrow specialisation in OSINT is one that has to be resisted. Why? Because no research task is ever as tidy as the customer’s requirements are likely to suggest. Third, is the inevitable realisation that good tool awareness is equivalent to good source awareness. Indeed, the right tool can determine whether you harvest the right information. -

The Braille Code: Past - Present - Future

TThhee EEdduuccaattoorr VOLUME XXI, ISSUE 2 January 2009 THE BRAILLE CODE: PAST - PRESENT - FUTURE A Publication of The International Council for Education of ICEVI People with Visual Impairment PRINCIPAL OFFICERS FOUNDING NON-GOVERNMENTAL PRINCIPAL OFFICERS ORGANISATIONS DEVELOPMENT PRESIDENT SECOND VICE PRESIDENT American Foundation ORGANISATIONS Lawrence F. Campbell Harry Svensson for the Blind Asian Foundation for the Overbrook School for the Blind National Agency for Special Carl R. Augusto Prevention of Blindness 6333 Malvern Avenue Needs Education and Philadelphia, PA 19151-2597 Schools 11 Penn Plaza, Suite 300 Grace Chan, JP USA Box 12161, SE- 102 26 New York, NY 10001 c/o The Hong Kong Society [email protected] Stockholm, SWEDEN USA for the Blind [email protected] [email protected] 248 Nam Cheong Street FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Perkins School for the Blind Shamshuipo, Kowloon Jill Keeffe TREASURER HONG KONG Steven M. Rothstein Centre for Eye Research Australia Nandini Rawal [email protected] 175 North Beacon Street University of Melbourne Blind People’s Association Watertown, MA 02472 CBM Jagdish Patel Chowk Department of Ophthalmology USA Locked Bag 8 Surdas Marg, Vastrapur Allen Foster [email protected] East Melbourne 8002 Ahmedabad 380 015 Nibelungenstrasse 124 AUSTRALIA INDIA Royal National Institute 64625 Bensheim [email protected] [email protected] of the Blind GERMANY [email protected] SECRETARY GENERAL Colin Low Mani, M.N.G. 105 Judd Street Norwegian Association of the London WC1H 9NE No.3, Professors’ Colony, Palamalai Road Blind and Partially Sighted UNITED KINGDOM (NABPS) SRK Vidyalaya Post, Coimbatore 641 020, Tamil Nadu, INDIA [email protected] [email protected] Arnt Holte INTERNATIONAL P.O. -

A Bibliography of Papers in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (2012): Volumes 7350–7399

A Bibliography of Papers in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (2012): Volumes 7350{7399 Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 14 October 2017 Version 1.01 Title word cross-reference (0,δ) [487]. (F; G) [158]. (k; r) [114]. 0 [527]. 1 [261, 527, 487]. 2 [229, 775, 878, 658, 180]. 2:5 [229]. 3 [570, 609, 229, 571, 190, 577, 582, 584, 468, 567, 180]. + [210]. α [131]. \ [160]. m ∆Σ [474]. EL [284]. ELHR+ [283]. [690]. F [812]. F2n [392]. GF(2 ) [386]. k [829, 832, 97, 68, 688, 466, 438]. K4 [141]. L [23, 389]. Lp [527]. λ [789]. N [532, 111]. O(log f) [112]. O(n3 log log n= log2 n) [142]. P [520]. Φ [440]. q [92]. m 2n−1k+1 n R [787]. SHACUN [560]. U2 [61]. x + ax [392]. x − a [391]. -Anonymity-Based [438]. -Center [97]. -Clustering [114]. -Completeness [23]. -Cover [789]. -D [229, 261]. -Differential [690]. -Dimensional [658]. -Fragment [158]. -Functions [389]. -Gram [92]. -Hiding [440]. -Indistinguishable [688]. -level [829]. -Median [832]. -Minor [141]. -norm [527]. -Pad [812]. -party [111]. -Round [487]. -Secure [487]. -Visibility [131]. -XORSAT [68]. 1 2 11th [1028, 997, 998, 996, 1034]. 12th [1022, 1019, 1012]. 13th [1029, 992, 1017, 1018]. 14th [1021]. 15th [1030]. 16th [1032, 1008, 1030]. -

Odt2braille Brings Braille to Your Office

odt2braille brings Braille to your Office Bert Frees, Christophe Strobbe & Jan Engelen* Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Kasteelpark Arenberg 10 3001 Heverlee-Leuven Belgium Abstract OpenOffice.org, the free and open-source productivity suite, is one step closer to beco- ming the ultimate authoring environment for accessible and high-standard documents. Thanks to odt2braille, an OpenOffice.org extension developed at the Katholieke Univer- siteit Leuven (Belgium), Braille is now available to anyone who knows how to use a word processor. odt2braille is powered by the open-source Braille translation engine Liblouis. Embosser communication and conversion to various Braille file formats is handled by the open-source Braille Utils API. The work described in this paper has been performed in the framework of the European R&D project ÆGIS (ÆGIS, 2011). 1 Introduction Braille production is an expensive and time-consuming business. Generally, dedi- cated Braille tools are used to convert regular print to Braille. These tools have grown from primitive Braille editors to specialised Braille authoring environments that provide automatic formatting and translation services. Still, often a lot of manual work is required. The typical workflow of a Braille production system is a multi-stage process. This is illustrated in illustration 1 below. If a document is not available in an electronic text format, it has to be scanned first, then converted with optical character re- cognition (OCR), verified, edited and possibly tagged to increase its machine readability. Next, the text file is automatically translated using a separate Braille tool. If the file was previously enriched with markup, automatic Braille formatting can be performed as well. -

Representing Emotions 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

REPRESENTING EMOTIONS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Helen Hills | 9781351904162 | | | | | Representing Emotions 1st edition PDF Book Our kids have had an exceptionally bad hand dealt to them the past few months. See all condition definitions - opens in a new window or tab. Anger can be a very upsetting emotion for children. Such dictionaries allow users to call up emoticons by typing words that represent them. In a first edition from Black Sparrow Press, the title page is in two or more colors, whereas the later printings have title pages in black only. All editions can be assumed firsts unless there are additional printings listed on the copyright page. Since at least the mids, first editions from Michael Joseph Ltd. Knopf, Inc. First editions from John Day Co. History of writing Grapheme. The conversation was taking place between many notable computer scientists, including David Touretzky , Guy Steele , and Jaime Carbonell. Pictorial representation of a facial expression using punctuation marks, numbers and letters. First editions from Philosophical Library have no additional printings indicated on the copyright page. Register now. This story of a girl experiencing intense feelings offers a road map for coping with anger. Early emoticons were the precursors to modern emojis, which are ever-developing predominantly on iOS and Android devices. Authority control GND : Available here. While Nabokov had suggested something similar to Fahlman, there was little analysis of the wider consideration of what Nabokov could do with the design. Get the item you ordered or get your money back. Standard works have no indication of printings within an edition: all printings of the first edition carry the same identification; only second printings with changed or added material are indicated. -

A Bi-Directional Bi-Lingual Translation Braille-Text System

J. King Saud University, Vol. 20, Comp. & Info. Sci., pp. 13-29,Riyadh (1428H./2008) A Bi-directional Bi-Lingual Translation Braille-Text System AbdulMalik S. Al-Salman Computer Science Department, College of Computer & Information Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia [email protected] (Received 17/01/2007; accepted for publication 12/12/2007) Abstract. Visually impaired people are an integral part of the society. However, their disabilities have made them to have less access to computers, the Internet, and high quality educational software than the people with clear vision. Consequently, they have not been able to improve on their own knowledge, and have significant influence and impact on the economic, commercial, and educational ventures in the society. One way to narrow this widening gap and see a reversal of this trend is to develop a system, within their economic reach, and which will empower them to communicate freely and widely using the Internet or any other information infrastructure. Over time, the Braille system has been used by the visually impaired for communication and contact with the outside world. Translation between one language and another, using the Braille coding system, has been limited, problematic, and in many cases, one-directional. This paper describes an Arabic Braille bi-directional and bi-lingual translation/editor system that does not need expensive equipments. With appropriate rule file for any other languages, this system can be generalized to facilitate communication among literate people regardless of their disabilities (visually impaired or sighted), income, languages, and geographical locations. 1. Introduction and Background enhance the information and communication capacity of those visually impaired people.