Iraq: Post-Saddam Governance and Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

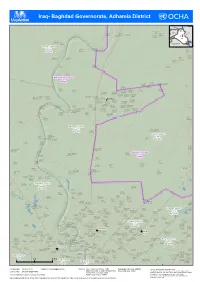

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adhamia District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adham( ia District ( ( Turkey Mosul! ! Albu Blai'a Erbil village Syria Ahmad al Al-Hajiyah IQ-P12429 Mahmud al Iran ( Mahmud River Al Bu Algah Khamis Baghdad Jadida Qaryat Albu IQ-P09040 IQ-P12203 IQ-P12398 IQ-P12326 Ramadi! ( IQ-P12308 ( ( Tannom ( !\ IQ-P12525 Jordan Najaf! Basrah! Hay Masqat Jurf Al IQ-P12295 Milah Bohroz Mahbubiyah ( SIaQ-uPd12i 2A(32rabia KIQu-wP1a2i3t22 ( IQ-P08417 ( ( ( Mohamed sakran Tarmia District IQ-P12335 Rashdiyah Muhammad (Noor village) Um Al al Jeb اﻟطﺎرﻣﯾﺔ IQ-P08355 Rumman IQ-P08339 ( ( IQ-P12386 IQ-D045 ( Al Halfayah village - 3 Mehdi al Ahmad Jamil Abdul Karim IQ-P12171 Hasan ( ( IQ-P09041 IQ-P08224 ( ( Al A`baseen IQ-P12332 ( village IQ-P12157 ( Sayyid Ahwiz Muhammad Musa Agha IQ-P08231 IQ-P08360 ( ( IQ-P12339 ( ( (( ( ( Fatah Chraiky IQ-P08312 IQ-P08307 ( ( ( Baghdad Governorate ( ( ﺑﻐداد IQ-G07 Qaryat Al Mohamad Khedidan 1 ( Khalaf Tameem Sakran IQ-P12318 ( ( ( Al-Mahmoud IQ-P12349 ( ( Al A'tb(a IQ-P12334 (( IQ-P12313 ( ( Qaryat ( village ( ( Darwesha IQ-P12161 ( Khalaf al IQ-P12359 ( ( Ulwan Muhammad Ja`atah Ali al Hajj ( Hussayniya - al `Abd al `Abbas IQ-P08333 Al Hussayniya IQ-P08297 Mahala 224 IQ-P12385 ( ( ( ( Al Hussainiya (Mahala 222) IQ-P12337 Al Husayniya ( IQ-P08330 ( ( ( - Mahalla 221 - Mahalla 213 IQ-P08264 ( IQ-P08243 IQ-P08251 Al Hussainiya Hussayniya - Al Hussayniya ( ( - Mahalla 216 Mahala 218 - Mahalla 220 IQ-P08253 ( IQ-P08329 IQ-P08261 ( Mahmud al Abdul Aziz Hay Al Waqf Al Hussainiya - ( ( Qal`at Jasim `Ulaywi Hamadi -

Crager on Burkman, 'Japan and the League of Nations: Empire and World Order, 1914-1938'

H-US-Japan Crager on Burkman, 'Japan and the League of Nations: Empire and World Order, 1914-1938' Review published on Wednesday, March 11, 2009 Thomas W. Burkman. Japan and the League of Nations: Empire and World Order, 1914-1938. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008. xv + 289 pp. $58.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8248-2982-7. Reviewed by Kelly E. Crager (Texas Tech University)Published on H-US-Japan (March, 2009) Commissioned by Yone Sugita Japanese Interwar Diplomacy In Japan and the League of Nations, Thomas W. Burkman recounts the history of Japan's foreign affairs from the close of World War I through the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Traditional understanding of Japan's role in the world during this era has been grossly simplified, according to the author, and a new and more balanced treatment of this topic was necessary to help bring about a fuller understanding of the developments in East Asia and the Pacific region prior to the Second World War. Although generally considered to have been an aggressive world power that largely eschewed international involvement to pursue its national interests, the empire, as Burkman insists, was very much committed to the promotion of ideals espoused by Woodrow Wilson and embodied in the League of Nations. Even though the Japanese readily embraced internationalist ideas, and participated fully, Japanese internationalism was influenced by peculiarly Japanese ideas concerning power and place. The author believes that when Wilsonian internationalism began to wane and when the economic pressures of the global depression began to set in, Japanese policymakers sought to protect national interests in the region rather than holding fast to internationalist policies that would make the empire vulnerable to foreign powers. -

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

CTC Sentinel Objective

NOVEMBER 2010 . VOL 3 . ISSUE 11-12 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC Sentinel OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy FEATURE ARTICLE 1 AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy in Yemen in Yemen By Barak Barfi By Barak Barfi REPORTS 5 Developing Policy Options for the AQAP Threat in Yemen By Gabriel Koehler-Derrick 9 The Role of Non-Violent Islamists in Europe By Lorenzo Vidino 12 The Evolution of Iran’s Special Groups in Iraq By Michael Knights 16 Fragmentation in the North Caucasus Insurgency By Christopher Swift 19 Assessing the Success of Leadership Targeting By Austin Long 21 Revolution Muslim: Downfall or Respite? By Aaron Y. Zelin 24 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts l-qa`ida in the arabian AQAP has avoided many of the domestic Peninsula (AQAP) is currently battles that weakened other al-Qa`ida the most successful of the affiliates by pursuing a shrewd strategy at three al-Qa`ida affiliates home in Yemen.3 The group has sought to Aoperating in the Arab world.1 Unlike its focus its efforts on its primary enemies— sibling partners, AQAP has neither been the Yemeni and Saudi governments, as plagued by internecine conflicts nor has well as the United States—rather than it clashed with its tribal hosts. It has also distracting itself by combating minor launched two major terrorist attacks domestic adversaries that would only About the CTC Sentinel against the U.S. homeland that were only complicate its grand strategy. Some The Combating Terrorism Center is an foiled by a combination of luck and the analysts have argued that this stems independent educational and research help of foreign intelligence agencies.2 from the lessons the group learned from institution based in the Department of Social al-Qa`ida’s failed campaigns in countries Sciences at the United States Military Academy, such as Saudi Arabia and Iraq. -

Terrorist Rehabilitation Terrorist

Terrorism / Political Violence Gunaratna Angell “This is a story of an effort to address the very fundamental challenge in this conflict, deradicalization … both in large mass populations, in small cells, in cliques and ultimately into the individual’s own thought process.” —Maj. Gen. Douglas Stone (retired) (from the Foreword) TERRORIST REHABILITATION Because terrorists are made, not born, it is critically important to world peace that detainees and inmates in uenced by violent ideology are deradicalized and rehabilitated back into society. Exploring the challenges in this formidable endeavor, Terrorist Rehabilitation: The U.S. Experience in Iraq demonstrates through the actual experiences of military personnel, defense contractors, and Iraqi nationals that deradicalization and rehabilitation programs can succeed and have the capability to positively impact thousands of would-be terrorists globally if utilized to their full capacity. Custodial and community rehabilitation of terrorists and extremists is a new frontier in the ght against terrorism. This forward-thinking volume: • Highlights the success of a rehabilitation program curriculum in Iraq • Encourages individuals and governments to embrace rehabilitation as the next most logical step in ghting terrorism • Examines the recent history of threat groups in Iraq • Demonstrates where the U.S. went awry in its war effort, and the steps it took to correct the situation • Describes religious, vocational training, education, creative expression, and Tanweer programs introduced to the detainee population • Provides insight into future steps based on lessons learned from current rehabilitation programs It is essential that we shift the focus from solely detainment and imprisonment to addressing the ideological mindset during prolonged incarceration. It is possible to effect an ideological transformation in detainees that qualies them to be reclassied as no longer posing a security threat. -

Iranian Strategy in Syria

*SBOJBO4USBUFHZJO4ZSJB #:8JMM'VMUPO KPTFQIIPMMJEBZ 4BN8ZFS BKPJOUSFQPSUCZ"&*ŦT$SJUJDBM5ISFBUT1SPKFDUJ/45*565&'035)&456%:0'8"3 .BZ All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ©2013 by Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project Cover Image: Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, and Hezbollah’s Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah appear together on a poster in Damascus, Syria. Credit: Inter Press Service News Agency Iranian strategy in syria Will Fulton, Joseph Holliday, & Sam wyer May 2013 A joint Report by AEI’s critical threats project & Institute for the Study of War ABOUT US About the Authors Will Fulton is an Analyst and the IRGC Project Team Lead at the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute. Joseph Holliday is a Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War. Sam Wyer served as an Iraq Analyst at ISW from September 2012 until February 2013. The authors would like to thank Kim and Fred Kagan, Jessica Lewis, and Aaron Reese for their useful insights throughout the writing and editorial process, and Maggie Rackl for her expert work on formatting and producing this report. We would also like to thank our technology partners Praescient Analytics and Palantir Technologies for providing us with the means and support to do much of the research and analysis used in our work. About the Institute for the Study of War The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. -

Dora – Baghdad – Government Employees – Forced Relocation – Kurdish Areas – Housing

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IRQ31805 Country: Iraq Date: 22 May 2007 Keywords: Iraq – Kurds – Shia – Dora – Baghdad – Government employees – Forced relocation – Kurdish areas – Housing This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Are insurgent/terrorist groups in Iraq targeting anyone who works alongside the pro- coalition forces in the rebuilding of Iraq? 2. Are they targeting Iraqi government workers who perform a co-ordinating role in this regard? 3. Do the insurgents target Shia Iraqis? 4. What is the level of instability within Dora for Kurdish Shiites? 5. Are Kurdish Shiites from Dora being forced to relocate from Dora? 6. Can Kurdish Shiites from Dora safely relocate elsewhere in Baghdad? 7. Can Kurdish Shiites safely relocate to the Kurdish areas of Iraq? 8. Are the local authorities in the Kurdish region imposing regulations to limit the influx of refugees from other parts of Iraq? 9. What has the impact of these internal refugees had on housing and rent in the Kurdish region? RESPONSE 1. Are insurgent/terrorist groups in Iraq targeting anyone who works alongside the pro-coalition forces in the rebuilding of Iraq? 2. Are they targeting Iraqi government workers who perform a co-ordinating -

Mcallister Bradley J 201105 P

REVOLUTIONARY NETWORKS? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by Bradley J. McAllister (Under the Direction of Sherry Lowrance) ABSTRACT This dissertation is simultaneously an exercise in theory testing and theory generation. Firstly, it is an empirical test of the means-oriented netwar theory, which asserts that distributed networks represent superior organizational designs for violent activists than do classic hierarchies. Secondly, this piece uses the ends-oriented theory of revolutionary terror to generate an alternative means-oriented theory of terrorist organization, which emphasizes the need of terrorist groups to centralize their operations. By focusing on the ends of terrorism, this study is able to generate a series of metrics of organizational performance against which the competing theories of organizational design can be measured. The findings show that terrorist groups that decentralize their operations continually lose ground, not only to government counter-terror and counter-insurgent campaigns, but also to rival organizations that are better able to take advantage of their respective operational environments. However, evidence also suggests that groups facing decline due to decentralization can offset their inability to perform complex tasks by emphasizing the material benefits of radical activism. INDEX WORDS: Terrorism, Organized Crime, Counter-Terrorism, Counter-Insurgency, Networks, Netwar, Revolution, al-Qaeda in Iraq, Mahdi Army, Abu Sayyaf, Iraq, Philippines REVOLUTIONARY NETWORK0S? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by BRADLEY J MCALLISTER B.A., Southwestern University, 1999 M.A., The University of Leeds, United Kingdom, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY ATHENS, GA 2011 2011 Bradley J. -

RRTA 836 (12 September 2012)

1201934 [2012] RRTA 836 (12 September 2012) DECISION RECORD RRT CASE NUMBER: 1201934 DIAC REFERENCE(S): CLF2011/135787 COUNTRY OF REFERENCE: Iraq TRIBUNAL MEMBER: Vanessa Moss DATE: 12 September 2012 PLACE OF DECISION: Perth DECISION: The Tribunal remits the matter for reconsideration with the direction that the applicant satisfies s.36(2)(a) of the Migration Act. STATEMENT OF DECISION AND REASONS APPLICATION FOR REVIEW 1. This is an application for review of a decision made by a delegate of the Minister for Immigration to refuse to grant the applicant a Protection (Class XA) visa under s.65 of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act). 2. The applicant who claims to be a citizen of Iraq, applied to the Department of Immigration for the visa on [date deleted under s.431(2) of the Migration Act 1958 as this information may identify the applicant] August 2011. 3. The delegate refused to grant the visa [in] January 2012, and the applicant applied to the Tribunal for review of that decision. RELEVANT LAW 4. Under s.65(1) a visa may be granted only if the decision maker is satisfied that the prescribed criteria for the visa have been satisfied. The criteria for a protection visa are set out in s.36 of the Act and Part 866 of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations 1994 (the Regulations). An applicant for the visa must meet one of the alternative criteria in s.36(2)(a), (aa), (b), or (c). That is, the applicant is either a person in respect of whom Australia has protection obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees as amended by the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (together, the Refugees Convention, or the Convention), or on other ‘complementary protection’ grounds, or is a member of the same family unit as a person in respect of whom Australia has protection obligations under s.36(2) and that person holds a protection visa. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization News (Bi-Monthly); United Nations Task Trative Apparatus of Its Own

UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization News (bi-monthly); United Nations Task trative apparatus of its own. (The Com- Force on Environment and Human Settle- mittee worked as advisory organ from ments: Report to the Secretary-General, 1922 until 1946 when its role was taken 15 June 1998, New York 1998. over by UNESCO.) Internet: Homepage of UNEP: www. In 1925, France, responding to a re- unep.org; UNEP Industry and Environment quest by the Assembly of the → League Unit: www.unepie.org/; International Insti- of Nations, after the latter had been un- tute for Sustainable Development, Earth Ne- gotiations Bulletin (reports on the sessions able to secure funding to maintain a sig- of the Governing Council of UNEP and on nificant office in Geneva, created the In- other important UNEP meetings): www.iisd. ternational Institute for Intellectual Co- ca; further: www.ecologic-events.de/ieg-con operation, a legally independent institu- ference/en/index.htm; www.reformtheun.org/ tion with a secretariat of its own, fi- index.php/united_nations/c495?theme=alt 2. nanced by the French government. The International Committee of Intellectual Co-operation continued to exist as the UNESCO – United Nations Institute’s Board of Trustees. Educational, Scientific and Cultural From the beginning, conflicts sur- Organization rounded the creation of UNESCO: Should it be a governmental or a non- I. Introduction governmental organization? (→ NGOs) UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Should the Organization be concerned Scientific and Cultural Organization) solely with education and culture was founded on the initiative of the (“UNECO”) or should it encompass fur- Conference of Allied Ministers of Edu- ther areas, such as science and commu- cation, set up during World War II. -

The Kurds in Post-Saddam Iraq

The Kurds in Post-Saddam Iraq Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs September 1, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS22079 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Kurds in Post-Saddam Iraq Summary The Kurdish-inhabited region of northern Iraq has been relatively peaceful and prosperous since the fall of Saddam Hussein. However, the Iraqi Kurds’ political autonomy, and territorial and economic demands, have caused friction with Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki and other Arab leaders of Iraq, and with Christian and other minorities in the north. Turkey and Iran were skeptical about Kurdish autonomy in Iraq but have reconciled themselves to this reality and have emerged as major investors in the Kurdish region of Iraq. Superimposed on Kurd-Arab di Despite limited agreements allowing for new oil exports from the Kurdish region, the major outstanding issues between the Kurds and the central government do not appear close to resolution. Tensions have increased now that Kurdish representation in two key mixed provinces has been reduced by the January 31, 2009, provincial elections. The disputes have nearly erupted into all-out violence between Kurdish militias and central government forces in mid-2009, potentially undermining the stability achieved throughout Iraq in 2008 and causing the U.S. military to propose new U.S. deployments designed to build confidence between Kurdish and government forces. The Obama Administration has not, to date, indicated that the Kurdish-central government disputes would derail or delay a major drawdown of U.S. forces in Iraq between now and August 2010.