Towards a Deleuzian Approach in Urban Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

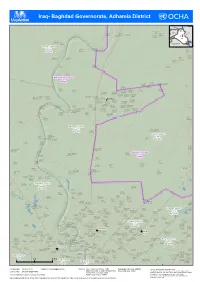

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adhamia District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adham( ia District ( ( Turkey Mosul! ! Albu Blai'a Erbil village Syria Ahmad al Al-Hajiyah IQ-P12429 Mahmud al Iran ( Mahmud River Al Bu Algah Khamis Baghdad Jadida Qaryat Albu IQ-P09040 IQ-P12203 IQ-P12398 IQ-P12326 Ramadi! ( IQ-P12308 ( ( Tannom ( !\ IQ-P12525 Jordan Najaf! Basrah! Hay Masqat Jurf Al IQ-P12295 Milah Bohroz Mahbubiyah ( SIaQ-uPd12i 2A(32rabia KIQu-wP1a2i3t22 ( IQ-P08417 ( ( ( Mohamed sakran Tarmia District IQ-P12335 Rashdiyah Muhammad (Noor village) Um Al al Jeb اﻟطﺎرﻣﯾﺔ IQ-P08355 Rumman IQ-P08339 ( ( IQ-P12386 IQ-D045 ( Al Halfayah village - 3 Mehdi al Ahmad Jamil Abdul Karim IQ-P12171 Hasan ( ( IQ-P09041 IQ-P08224 ( ( Al A`baseen IQ-P12332 ( village IQ-P12157 ( Sayyid Ahwiz Muhammad Musa Agha IQ-P08231 IQ-P08360 ( ( IQ-P12339 ( ( (( ( ( Fatah Chraiky IQ-P08312 IQ-P08307 ( ( ( Baghdad Governorate ( ( ﺑﻐداد IQ-G07 Qaryat Al Mohamad Khedidan 1 ( Khalaf Tameem Sakran IQ-P12318 ( ( ( Al-Mahmoud IQ-P12349 ( ( Al A'tb(a IQ-P12334 (( IQ-P12313 ( ( Qaryat ( village ( ( Darwesha IQ-P12161 ( Khalaf al IQ-P12359 ( ( Ulwan Muhammad Ja`atah Ali al Hajj ( Hussayniya - al `Abd al `Abbas IQ-P08333 Al Hussayniya IQ-P08297 Mahala 224 IQ-P12385 ( ( ( ( Al Hussainiya (Mahala 222) IQ-P12337 Al Husayniya ( IQ-P08330 ( ( ( - Mahalla 221 - Mahalla 213 IQ-P08264 ( IQ-P08243 IQ-P08251 Al Hussainiya Hussayniya - Al Hussayniya ( ( - Mahalla 216 Mahala 218 - Mahalla 220 IQ-P08253 ( IQ-P08329 IQ-P08261 ( Mahmud al Abdul Aziz Hay Al Waqf Al Hussainiya - ( ( Qal`at Jasim `Ulaywi Hamadi -

12. Selma Harrington Et Al 11-3-178-192

Selma Harrington, Branka Dimitrijević, Ashraf M. Salama Archnet-IJAR, Volume 11 - Issue 3 - November 2017 - (178-192) – Regular Section Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research www.archnet-ijar.net/ -- https://archnet.org/collections/34 MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE, CONFLICT, HERITAGE AND RESILIENCE: THE CASE OF THE HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v11i3.1330 Selma Harrington, Branka Dimitrijević, Ashraf M. Salama Keywords Abstract Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the successor states of conflict and identity former Yugoslavia, with a history of dramatic conflicts and narratives; Modernist ruptures. These have left a unique heritage of interchanging architecture; public function; prosperity and destruction, in which the built environment and resilience; reuse of architecture provide a rich evidence of the many complex architectural heritage identity narratives. The public function and architecture of the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, once purposely built to commemorate the national liberation in World War 2, encapsulates the current situation in the country, which is navigating through a complicated period of reconstruction and transformation after the war in 1990s. Once considered as the embodiment of a purist Modernist architecture, now a damaged structure with negligible institutional patronage, the Museum shelters the fractured artefacts of life during the three and a half year siege of ArchNet -IJAR is indexed and Sarajevo. This paper introduces research into symbiotic listed in several databases, elements of architecture and public function of the Museum. including: The impact of conflict on its survival, resilience and continuity of use is explored through its potentially mediatory role, and • Avery Index to Architectural modelling for similar cases of reuse of 20th century Periodicals architectural heritage. -

The Application of Visualisation

THE APPLICATION OF VISUALISATION TOOLS TO ENABLE ARCHITECTS TO EXPLORE THE DYNAMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SMART MATERIALS IN A CONTEMPORARY SHANASHIL BUILDING DESIGN ELEMENT FOR HOT ARID CLIMATES Tamarah Alqalami Ph.D. Thesis 2017 THE APPLICATION OF VISUALISATION TOOLS TO ENABLE ARCHITECTS TO EXPLORE THE DYNAMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SMART MATERIALS IN A CONTEMPORARY SHANASHIL BUILDING DESIGN ELEMENT FOR HOT ARID CLIMATES School of the Built Environment University of Salford, Salford, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, August 2017 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... I LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................ V LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ....................................................................................................................... X DEDICATION ...................................................................................................................................... XI ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. XII ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

Archnet 2.0: Building a New Asset Management System for MIT’S Online Architectural Library of the Islamic World

Archnet 2.0: Building a new asset management system for MIT’s online architectural library of the Islamic World Andrea Schuler is the Visual Resources Librarian for Islamic Architecture in the Aga Khan Documentation Center (AKDC) at MIT. In that role she manages the creation, cataloging, uploading and storage of digital assets from the AKDC’s vast collections. She administers the Aga Khan Visual Archive and provides access to the Documentation Center’s visual collections for the MIT community and for a worldwide community of users. She also contributes content to Archnet as part of the AKDC team. Abstract Archnet 2.0 is a new front end website and back end cataloging tool and asset management system for Archnet (http://archnet.org), the largest openly accessible online architectural library focusing on the Muslim world. The site, a partnership between the Massachusetts Institute for Technology and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), contains articles and publications, images, maps and drawings, video, archival material, course syllabi, and site records relating to architecture in the Islamic world. By 2012, when the Aga Khan Documentation Center (AKDC) at MIT, part of the MIT Libraries, took over the digital library, the site has become dated and was no longer meeting the needs of its users. A software development firm was hired to build new front and back ends for the site. This paper explores the development of the new back end cataloging and asset management tool, including the reasoning behind building a new tool from scratch; considerations during development such as database structure, fields, and migration; highlights of features; and lessons learned from the process. -

Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, Ve Aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Jonathan Vimr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Vimr, Jonathan, "Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 211. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 Suggested Citation: Vimr, Jonathan (2013). Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Abstract Just as architectural history traditionally takes the form of a march of styles, so too do preservationists repeatedly campaign to save seminal works of an architectural manner several decades after its period of prominence. This is currently happening with New Brutalism and given its age and current unpopularity will likely soon befall postmodern historicism. In hopes of preventing the loss of any of the manner’s preeminent works, this study provides professionals with a framework for evaluating the significance of postmodern historicist designs in relation to one another. Through this, the limited resources required for large-scale preservation campaigns can be correctly dedicated to the most emblematic sites. Three case studies demonstrate the application of these criteria and an extended look at recent preservation campaigns provides lessons in how to best proactively preserve unpopular sites. -

Conserving the Palestinian Architectural Heritage

Jihad Awad, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 451–460 CONSERVING THE PALESTINIAN ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE JIHAD AWAD Architectural Engineering Department, Ajman University of Science & Technology, United Arab Emirates. ABstract Despite the difficult situation in West Bank, the Palestinians were able to, during the last three decades, preserve a huge part of their architectural heritage. This is mainly due to the notion that this issue was considered as an essential part of the struggle against occupation and necessary to preserve their identity. This paper will concentrate mainly on the conservation efforts and experience in West Bank, Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. It covers not only examples from major cities but also some important ones in the villages. Due to the special situation of being occupation, and the absence of a central au- thority responsible for heritage conservation, several entities were established and became involved in conservation, with diverse goals and approaches. Although it started during the last three decades, the Palestinian experience in conservation has received international recognition for some distinguished successful examples. It became in some cases a good reference for others outside Palestine. The main goal of this paper is to present the Palestinian experiment in conservation and to highlight the reasons behind the successful examples and find out the obstacles and difficulties in other cases. It shows that for the Palestinians preserving the architectural heritage became a part of their cultural resistance and efforts to maintain their national identity. This paper depends on a descriptive method based on pub- lications and some site visits, in addition to direct contact with major institutions involved in heritage conservation in Palestine. -

Arabesques, Unicorns, and Invisible Masters: the Art Historian's Gaze

ARABESQUES, UNICORNS, AND INVISIBLE MASTERS 213 EVA-MARIA TROELENBERG ARABESQUES, UNICORNS, AND INVISIBLE MASteRS: THE ART HISTORIAN’S GAZE AS SYMPTOMATIC ACTION? Is it still true that art history, traditionally understood as be to look at these objects. As Margaret Olin has argued, an explicitly object-based discipline, lacks a thorough “The term ‘gaze’ … leaves no room to comprehend the understanding of an “action tradition” that could be em- visual without reference to someone whose vision is un- ployed to explain and theorize, for example, artistic der discussion.”3 Although she refers generally to the agency? And that therefore art history, as opposed to gaze of all possible kinds of beholders, viewers, or spec- other disciplines such as sociology or linguistic studies, tators, she also stresses: “While most discourse about the has found it particularly difficult to look at its own his- gaze concerns pleasure and knowledge, however, it gen- toriography in terms of academic or scholarly action or erally places both of these in the service of issues of agency? Such explanations were employed until quite power, manipulation, and desire”; furthermore, “The recently when expounding the problem of a general de- choice of terms from this complex can offer a key to the lay in critical historiography concerning the discipline’s theoretical bent or the ideology of the theorist.”4 Ac- traditions and methods, particularly in relation to Ger- cordingly, an action-based theory of historiography man art history under National Socialism.1 must find -

WAIPA-Annual-Report-2004.Pdf

Note The WAIPA Annual Report 2004 has been produced by WAIPA, in cooperation with the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). This report was prepared by Vladimir Pankov. Beatrice Abel provided editorial assistance. Teresita Sabico and Farida Negreche provided assistance in formatting the report. WAIPA would like to thank all those who have been involved in the preparation of this report for their various contributions. For further information on WAIPA, please contact the WAIPA Secretariat at the following address: WAIPA Secretariat Palais des Nations, Room E-10061 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (41-22) 907 46 43 Fax: (41-22) 907 01 97 Homepage: http://www.waipa.org UNCTAD/ITE/IPC/2005/3 Copyright @ United Nations, 2005 All rights reserved 2 Table of Contents Page Note 2 Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgements 4 Facts about WAIPA 5 WAIPA Map 8 Letter from the President 9 Message from UNCTAD 10 Message from FIAS 11 Overview of Activities 13 The Study Tour Programme 24 WAIPA Elected Office Bearers 25 WAIPA Consultative Committee 27 List of Participants: WAIPA Executive Meeting, Ninth Annual WAIPA Conference and WAIPA Training Workshops 29 Statement of Income and Expenses - 2004 51 WAIPA Directory 55 ANNEX: WAIPA Statute 101 3 Acknowledgements WAIPA would like to thank Ernst & Young – International Location Advisory Services (E&Y–ILAS); IBM Business Consulting Services – Plant Location International (IBM Business Consulting Services – PLI); and OCO Consulting for contributing their time and expertise to the WAIPA Training Programme. Ernst & Young – ILAS IBM Business Consulting Services – PLI OCO Consulting 4 Facts about WAIPA What is WAIPA? The World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies (WAIPA) was established in 1995 and is registered as a non-governmental organization (NGO) in Geneva, Switzerland. -

Dora – Baghdad – Government Employees – Forced Relocation – Kurdish Areas – Housing

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IRQ31805 Country: Iraq Date: 22 May 2007 Keywords: Iraq – Kurds – Shia – Dora – Baghdad – Government employees – Forced relocation – Kurdish areas – Housing This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Are insurgent/terrorist groups in Iraq targeting anyone who works alongside the pro- coalition forces in the rebuilding of Iraq? 2. Are they targeting Iraqi government workers who perform a co-ordinating role in this regard? 3. Do the insurgents target Shia Iraqis? 4. What is the level of instability within Dora for Kurdish Shiites? 5. Are Kurdish Shiites from Dora being forced to relocate from Dora? 6. Can Kurdish Shiites from Dora safely relocate elsewhere in Baghdad? 7. Can Kurdish Shiites safely relocate to the Kurdish areas of Iraq? 8. Are the local authorities in the Kurdish region imposing regulations to limit the influx of refugees from other parts of Iraq? 9. What has the impact of these internal refugees had on housing and rent in the Kurdish region? RESPONSE 1. Are insurgent/terrorist groups in Iraq targeting anyone who works alongside the pro-coalition forces in the rebuilding of Iraq? 2. Are they targeting Iraqi government workers who perform a co-ordinating -

Iraq's Civil War, the Sadrists and the Surge

IRAQ’S CIVIL WAR, THE SADRISTS AND THE SURGE Middle East Report N°72 – 7 February 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. BAGHDAD’S CIVIL WAR AND THE SADRISTS’ ASCENT................................. 2 A. HOW THE SADRISTS EXPANDED THEIR TERRITORY ...............................................................2 B. NEUTRALISING THE POLICE...................................................................................................4 C. DEALING IN VIOLENCE..........................................................................................................6 III. THE SADRISTS’ REVERSAL OF FORTUNE .......................................................... 8 A. AN INCREASINGLY UNDISCIPLINED MOVEMENT ...................................................................8 B. THE SADRISTS’ TERRITORIAL REDEPLOYMENT...................................................................10 C. ARE THE SADRISTS SHIFTING ALLIANCES?.............................................................................13 D. A CHANGE IN MODUS OPERANDI........................................................................................16 IV. A SUSTAINABLE CEASEFIRE? .............................................................................. 18 V. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................ -

REPUBLIC of IRAQ MINISTRY of PLANNING NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2013-2017 BAGHDAD JANUARY 2013 2013 2017 Republic of Iraq Ministry of Planning

الفصل الثالث اجنازات اجهزة ومراكز الوزارة الفصل الثالث اجنازات اجهزة ومراكز الوزارة NATIONAL DEVELOPMENTNATIONAL PLAN REPUBLIC OF IRAQ MINISTRY OF PLANNING NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2013-2017 BAGHDAD JANUARY 2013 2013 2017 Republic of Iraq Ministry of Planning National Development Plan 2013-2017 Baghdad January 2013 Preface A clear and defined path for development can only be mapped out through the creation of medium- and long-term plans and strategies built on sound methodology and an ac- curate reading of the economic, social, urban, and environmental reality. All the possibili- ties, problems, and challenges of distributing the available material and human resources across competing uses must be taken into consideration to maximize results for the national economy and the broader society. Three years of implementation of the 2010-2014 National Development Plan have resulted in important successes in certain areas and setbacks in others. It’s not fair to say that respon- sibility for the failures lies with the policies and programs adopted in the previous plan. The security and political dimensions of the surrounding environment, the executive capabilities of the ministries and governorates, the problems that continue to hinder the establishment and implementation of projects, weak commitment to the plan, and the weak link between annual investment budgets and plan priorities, along with the plan targets and the means of reaching these targets are all factors that contributed to these setbacks in certain areas and require that this plan be met with a high degree of compliance. The official decision announcing the 2010-2014 National Development Plan document in- cluded following up on plan goals in 2012 to monitor achievements and diagnose failures.