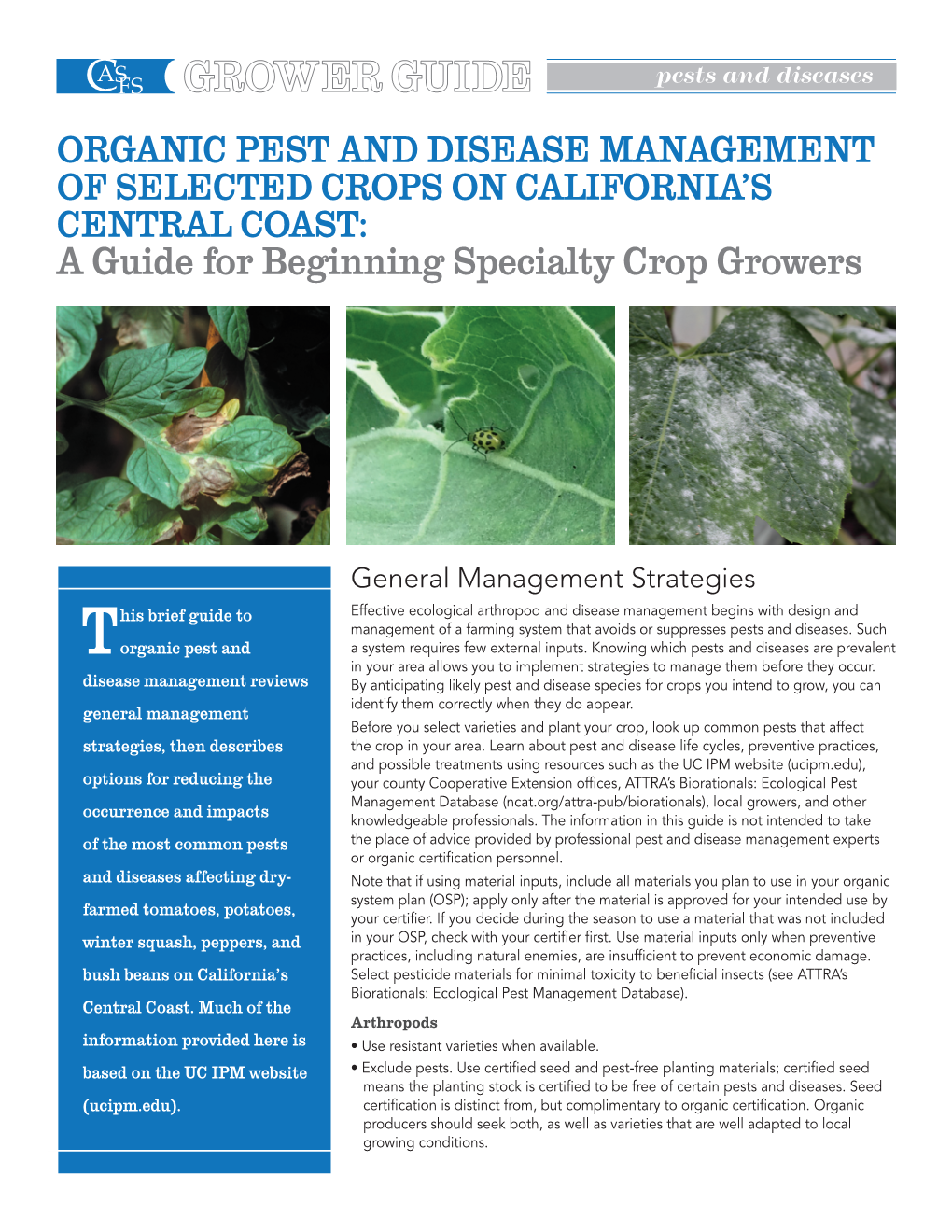

A Guide for Beginning Specialty Crop Growers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LD5655.V855 1997.W355.Pdf (2.586Mb)

Plant Diversity and its Effects on Populations of Cucumber Beetles and Their Natural Enemies in a Cucurbit Agroecosystem by Jason Walker Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HORTICULTURE APPROVED: ofl, 4 Lalla, 5 (John S. Caldwell (chair) Inhul x. UM 1 Sows Wl Robert H. Johes Ronald D. Morse January 9, 1997 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Community ecology, cucumbers, Pennsylvania leatherwing, Diptera, lady beetles, wild violet, clover, goldenrod Ross VRS Va? oa PLANT DIVERSITY AND ITS EFFECTS ON POPULATIONS OF CUCUMBER BEETLES AND THEIR NATURAL ENEMIES IN A CUCURBIT AGROECOSYSTEM by Jason Walker John Caldwell, Chairman Horticulture (Abstract) Populations of striped cucumber beetles (Acalymma vittatum Fabr.), spotted cucumber beetles (Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber), western cucumber beetles (Acalymma trivittatum Mann.), Pennsylvania leatherwings (Chauliognathus pennsylvanicus DeGeer), Diptera (Order: Diptera), lady beetles (Order: Coleoptera, Family: Coccinellidae), hymenoptera (Order: Hymenoptera), and spiders (Order: Araneae) in a cucumber field and a bordering field of uncultivated vegetation were assessed using yellow sticky traps to determine: 1) the relative abundances of target insects across the uncultivated vegetation and the crop field, 2) relationships between target insects and plant species. In both years populations striped and spotted cucumber beetles and Pennsylvania leatherwings (only in 1995) increased Significantly and Diptera decreased significantly in the direction of the crop. The strength of these relationships increased over the season to a peak in August in 1995 and July in 1996 and then decreased in September in both years. There were significant correlations between Diptera and sweet-vernal grass in 1995. -

Transcriptome Sequencing of the Striped Cucumber Beetle, Acalymma Vittatum (F.), Reveals Numerous Sex-Specific Transcripts and Xenobiotic Detoxification Genes

Article Transcriptome Sequencing of the Striped Cucumber Beetle, Acalymma vittatum (F.), Reveals Numerous Sex-Specific Transcripts and Xenobiotic Detoxification Genes Michael E. Sparks 1 , David R. Nelson 2 , Ariela I. Haber 1, Donald C. Weber 1 and Robert L. Harrison 1,* 1 Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Laboratory, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA; [email protected] (M.E.S.); [email protected] (A.I.H.); [email protected] (D.C.W.) 2 Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Biochemistry, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-504-5249 Received: 24 September 2020; Accepted: 22 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: Acalymma vittatum (F.), the striped cucumber beetle, is an important pest of cucurbit crops in the contintental United States, damaging plants through both direct feeding and vectoring of a bacterial wilt pathogen. Besides providing basic biological knowledge, biosequence data for A. vittatum would be useful towards the development of molecular biopesticides to complement existing population control methods. However, no such datasets currently exist. In this study, three biological replicates apiece of male and female adult insects were sequenced and assembled into a set of 630,139 transcripts (of which 232,899 exhibited hits to one or more sequences in NCBI NR). Quantitative analyses identified 2898 genes differentially expressed across the male–female divide, and qualitative analyses characterized the insect’s resistome, comprising the glutathione S-transferase, carboxylesterase, and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase families of xenobiotic detoxification genes. In summary, these data provide useful insights into genes associated with sex differentiation and this beetle’s innate genetic capacity to develop resistance to synthetic pesticides; furthermore, these genes may serve as useful targets for potential use in molecular-based biocontrol technologies. -

Abstracts For

ABSTRACTS FOR 92nd ANNUAL MEETING PACFIC BRANCH, ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA March 30 – April 2, 2008 Embassy Suites Napa Valley Napa, California, USA 1. IMPROVED MANAGEMENT OF CUCUMBER BEETLES IN CALIFORNIA MELONS Andrew Pedersen1, Larry D. Godfrey1, Carolyn Pickel2 1Dept. of Entomology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA 2University of California Cooperative Extension, 142 Garden Highway, Suite A, Yuba City, CA In recent years cucumber beetles (Chrysomelidae) have become increasingly problematic as pests of melons grown in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys of California. The primary source of damage comes from feeding on the rind of the developing fruit by adults, and occasionally by larvae, which creates corky lesions and renders the fruit unmarketable, especially for export. Larval feeding on the roots may also be contributing. There are two species of cucumber beetles that are pests of California melons: Western spotted cucumber beetle (Diabrotica undecimpunctata undecimpunctata Mannerheim) and Western striped cucumber beetle (Acalymma trivittatum Mannerheim). Monitoring of both species in Sutter and Colusa Counties began mid-season in July 2007 to investigate biology, distribution, and population dynamics but has not yet produced conclusive results. A study comparing the effects of different insecticide treatments with and without a cucurbitacin-based feeding stimulant called Cidetrak® was initiated in the summer of 2007. Cidetrak did appear to reduce beetle numbers when combined with either Spinosad or low doses of Sevin XLR Plus. None of the treatments however, reduced cosmetic damage sustained to the fruit. The limited plot size may have compromised the integrity of the treatments. Future studies will utilize field cages or larger plots in order to prevent movement between treatment plots. -

Entomología Agrícola

ENTOMOLOGÍA AGRÍCOLA EFECTIVIDAD BIOLÓGICA DE INSECTICIDAS CONTRA NINFAS DE Diaphorina citri KUWAYAMA (HEMIPTERA: PSYLLIDAE) EN EL VALLE DEL YAQUI, SON. Juan José Pacheco-Covarrubias. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP), Campo Experimental Norman E. Borlaug. Calle Dr. Norman E. Borlaug Km. 12, CP 85000, Cd. Obregón, Son. [email protected]. RESUMEN. El Psilido Asiático de los Cítricos actualmente es la principal plaga de la citricultura en el mundo por ser vector de la bacteria Candidatus liberobacter que ocasiona el Huanglongbing. Tanto adultos como ninfas de cuarto y quinto instar pueden ser vectores de esta enfermedad por lo que su control es básico para minimizar este problema. Se realizó esta investigación para conocer el comportamiento de los estados inmaduros de la plaga a varias alternativas químicas de control. El análisis de los datos de mortalidad muestra que las poblaciones de Diaphorina tratadas con: clorpirifós, dimetoato, clotianidin, dinotefurán, thiametoxan, endosulfán, imidacloprid, lambdacialotrina, zetacipermetrina, y lambdacialotrina registraron mortalidades superiores al 85%. Por otra parte, las poblaciones tratadas con: pymetrozine (pyridine azomethines) y spirotetramat (regulador de crecimiento de la síntesis de lípidos) a las dosis evaluadas no presentaron efecto tóxico por contacto o efecto fumigante sobre la población antes mencionada. Palabras Clave: psílido, Diaphorina citri, ninfas, insecticidas. ABSTRACT. The Asian Citrus Psyllid, vector of Candidatus Liberobacter, bacteria that causes Huanglongbing disease, is currently the major pest of citrus in the world. Both, adults and nymphs of fourth and fifth instar can be vectors this pathogen, and therefore their control is essential to prevent increase and spread of disease. This research was carried out to evaluate the biological response of the immature stages of the pest to several chemical alternatives. -

1089 Willamette Falls Drive, West Linn, OR 97068 | Tel: +1 (503) 342 - 8611 | Fax: +1 (314) 271-7297 [email protected] | |

2019 1089 Willamette Falls Drive, West Linn, OR 97068 | tel: +1 (503) 342 - 8611 | fax: +1 (314) 271-7297 [email protected] | www.alphascents.com | Our Story The story of Alpha Scents, Inc. begins with president and founder, Dr. Darek Czokajlo. When speaking about entomolo- gy, he will laugh and say the interest began “in the womb.” Driven by his passion for science and technology, he strives for eco- nomic security, which can be largely attributed to his upbringing in communist Poland. How do you become economically stable according to Darek? By building a company that is customer focused: embracing honesty, respect, trust and support, the rest are details. When discussing what characteristics Alpha Scents, Inc. reflects, it’s clear that the vision for the company is shaped by a desire to be loyal to all stakeholders, including customers, vendors, and his employees. Since childhood, Darek was involved with biology clubs and interest groups, fueling his passion for the sciences and leading him to study forestry and entomology during his undergraduate and master’s studies. In 1985 he started studying and experimenting with insect traps, in particular bark beetle traps baited with ethanol lures. This is how Darek started honing his speciali- zation and began asking the intriguing question of, “How could we use scents to manage insects?” In 1989, right before the fall of Communism, Darek emi- grated to Canada and in 1993 started his PhD program in the field of Insect Chemical Ecology in Syracuse, New York. After his graduation in 1998, one of his professors recommended Darek to a company in Portland, Oregon. -

DISTRIBUCIÓN DE ADULTOS DE LOS GÉNEROS Diabrotica Y Acalymma (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELIDAE) EN DURANGO, MÉXICO Adult Distributio

DISTRIBUCIÓN DE ADULTOS DE LOS GÉNEROS Diabrotica Y Acalymma (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELIDAE) EN DURANGO, MÉXICO Adult distribution of the Genus Diabrotica and Acalymma (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Durango State, Mexico. Rebeca Álvarez Zagoya1*, J. Francisco Pérez Domínguez2, Marco A. Márquez Linares1, Norma Almaráz Abarca1*. 1CIIDIR-IPN U. Dgo., Sigma S/N, Fracc. 20 de Noviembre II, Durango 34220, Dgo. Correo-e: [email protected]. *Becarias COFAA. Proy. SIP-IPN 20080412. 2 Investigador, INIFAP-Ocotlán. Palabras Clave: Plagas agrícolas, cultivos y maleza, abundancia. Introducción Los crisomélidos son un grupo de insectos fitófagos de importancia agrícola, dentro de los cuales se encuentran el género Diabrotica, comúnmente conocidos como diabróticas, que en estado larval afecta a la raíz del maíz y el género Acalymma, como catarinita occidental rayada del pepino. Estos géneros forman parte de las especies de mayor importancia para los cultivos de maíz y de hortalizas, entre otros (Metcalf, 1986). A nivel mundial existen diez especies del género Diabrotica que son las plagas agrícolas de importancia económica, mientras que del género Acalymma presenta un número menor (Wilcox,1972). Sin embargo, los efectos producidos por las poblaciones de estos insectos, continúan resaltando la importancia de su estudio, ya que en México han sido pocos los estudios efectuados al respecto a lo largo y ancho del país. Parte de los trabajos realizados en nuestro país, han sido algunas determinaciones taxonómicas regionales, evaluaciones poblacionales, pérdidas en cultivos, insumos invertidos para su control, así como la búsqueda de enemigos naturales y de evaluación de la respuesta a la actividad química de compuestos (Domínguez y Carrillo, 1976; Álvarez, 1985 a, b; De la Paz, 1994; Pérez y Álvarez, 2002, 2003; González et al., 2003; García et al., 2003; Giordano et al., 2004; Gámez y Eben, 2005; Álvarez y Domínguez, 2006; Toepfer et al., 2008). -

Open Final Draft Lewis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Entomology ADVANCING ECOLOGICALLY BASED MANAGEMENT FOR ACALYMMA VITTATUM, A KEY PEST OF CUCURBITS A Thesis in Entomology by Margaret Theresa Lewis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science May 2015 ii The thesis of Margaret Theresa Lewis was reviewed and approved* by the following: Shelby Fleischer Professor of Entomology Thesis Advisor John Tooker Associate Professor of Entomology and Extension Specialist Elsa Sanchez Associate Professor of Horticultural Systems Management Gary Felton Professor of Entomology Head of the Department of Entomology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Striped cucumber beetle, Acalymma vittatum (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), is a key pest of cucurbit crops in the northeastern United States. Systemic and foliar insecticides provide consistent control of the adult beetles and are the primary management tool available to growers. However, many of these chemicals are excluded from use in organic production systems. Additionally, there are concerns about the potential for development of insecticide resistant populations of A. vittatum and the non- target effects on beneficial insects within cucurbit cropping systems. In this thesis, I explore alternative management options for A. vittatum, considering both efficacy and the potential for integration into an ecologically based pest management system. I first take a systems based approach to A. vittatum management, considering how horticultural production practices shape pest and beneficial insect communities in cucurbit systems. In a two year field experiment, I measured how soil production systems and row cover use influence ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) activity density. The presence or absence of a row cover had no significant effect. -

A Review of the Natural Enemies of Beetles in the Subtribe Diabroticina (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): Implications for Sustainable Pest Management S

This article was downloaded by: [USDA National Agricultural Library] On: 13 May 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 908592637] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biocontrol Science and Technology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713409232 A review of the natural enemies of beetles in the subtribe Diabroticina (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): implications for sustainable pest management S. Toepfer a; T. Haye a; M. Erlandson b; M. Goettel c; J. G. Lundgren d; R. G. Kleespies e; D. C. Weber f; G. Cabrera Walsh g; A. Peters h; R. -U. Ehlers i; H. Strasser j; D. Moore k; S. Keller l; S. Vidal m; U. Kuhlmann a a CABI Europe-Switzerland, Delémont, Switzerland b Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, Saskatoon, SK, Canada c Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, AB, Canada d NCARL, USDA-ARS, Brookings, SD, USA e Julius Kühn-Institute, Institute for Biological Control, Darmstadt, Germany f IIBBL, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, MD, USA g South American USDA-ARS, Buenos Aires, Argentina h e-nema, Schwentinental, Germany i Christian-Albrechts-University, Kiel, Germany j University of Innsbruck, Austria k CABI, Egham, UK l Agroscope ART, Reckenholz, Switzerland m University of Goettingen, Germany Online Publication Date: 01 January 2009 To cite this Article Toepfer, S., Haye, T., Erlandson, M., Goettel, M., Lundgren, J. G., Kleespies, R. G., Weber, D. C., Walsh, G. Cabrera, Peters, A., Ehlers, R. -U., Strasser, H., Moore, D., Keller, S., Vidal, S. -

Center • Research • Briefs

The CENTER for AGROECOLOGY & SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS UNIVersity OF CALIFORNIA, Santa CruZ Research BRIEF #13, FALL 2010 Can Hedgerows Attract Beneficial Insects and Improve Pest Control? A Study of Hedgerows on Central Coast Farms – Tara Pisani Gareau1 and Carol Shennan2 edgerows began to appear on Central importance, while not creating or exacerbat- Coast farm edges in 2000, due largely ing pest problems. It is often assumed that if to the efforts of the non-profit Com- natural enemies are attracted and retained in H a CENTER munity Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF). farms with added habitat, then their control of On the Central Coast, hedgerows consist of pests in crop fields will also increase. However, • linear assemblages of trees, shrubs, herbs and in order for biological control to take place, grasses, many of them native species, which insect natural enemies must disperse from RESEARCH provide multiple services to farms. flowering habitat into the crop field to either When contour-planted on a sloped field, parasitize (if a parasitoid) or consume (if a • mature hedgerows with deep and fibrous root predator) their host prey. The results of studies systems can reduce soil erosion as well as that have tested the effects of added habitat on absorb mobile nutrients like nitrate (Kinama predation or parasitism rates in the field are BRIEFS et al. 2007, Bu et al. 2008). Tall, dense hedge- often quite variable (Lee and Heimpel 2005, rows act as a windbreak, which can reduce Pfiffner et al. 2009) or show no apparent effect crop field edge effects such as stunted growth (Rebek et al. -

Triped Cucumber Beetle Acalymma Vittatum F. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)1 Braden Evans and Justin Renkema2

EENY-707 Triped Cucumber Beetle Acalymma vittatum F. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)1 Braden Evans and Justin Renkema2 Introduction The striped cucumber beetle, Acalymma vittatum F. (Figure 1) is a serious agricultural pest of plants in the family Cucurbitaceae in eastern North America. Crops affected by larval and adult feeding include cucumber, Cucumis sa- tivus L., cantaloupe, Cucumis melo L., pumpkin, Cucurbita pepo L., and other Cucurbita spp. (Dill and Kirby 2016). The striped cucumber beetle is a vector of the plant disease bacterial wilt (Eaton 2016). Though the striped cucumber beetle occurs throughout Florida, it is the least commonly reported among three chrysomelid species on cucurbit crops in the state. The spotted cucumber beetle, Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber, and banded cucumber beetle, Diabrotica balteata LeConte, are more common in Florida, causing damage symptoms that are similar to Figure 1. The striped cucumber beetle, Acalymma vittatum F. striped cucumber feeding damage (Webb 2010). Credits: John Capinera, UF/IFAS Distribution Description and Life Cycle The striped cucumber beetle is indigenous to North Unmated adults of the striped cucumber beetle overwinter America, widespread in the east, from as far south as under organic debris in hedgerows and field margins Mexico, and north into southern Canada (CABI 2018). surrounding plots of land that were cultivated with cucurbit Though the species has been reported in western states and crops. Adults emerge in the spring when soil temperatures provinces, the Rocky Mountains are considered the western reach 13°C (55°F) and feed on pollen and foliage of alterna- limit of its range. It is replaced in the west by Acalymma tive host plants, such as willow, apple, hawthorn, goldenrod, trivittatum Mannerheim, the western striped cucumber and aster, when cucurbits are unavailable (Dill and Kirby beetle (Reilly 2003). -

2018 Myanmar PERSUAP

BUREAUS FOR ASIA AND FOOD SECURITY PESTICIDE EVALUATION REPORT AND SAFE USE ACTION PLAN (PERSUAP) IEE AMENDMENT: §216.3(B) PESTICIDE PROCEDURES PROJECT/ACTIVITY DATA Project/Activity Name: Feed the Future Cambodia Harvest II (“Harvest II”) Amendment #: 1 Geographic Location: South East Asia (Cambodia) Implementation Start/End: 1/1/2017 to 12/31/2021 Implementing Partner(s): Abt Associates, International Development Enterprises (iDE), Emerging Markets Consulting (EMC) Tracking ID/link: Tracking ID/link of Related IEE: Asia 16-042 https://ecd.usaid.gov/repository/pdf/46486.pdf Tracking ID/link of Other Related Analyses: ORGANIZATIONAL/ADMINISTRATIVE DATA Implementing Operating Unit: Cambodia Funding Operating Unit: Bureau for Asia Initial Funding Account(s): $17.5 M Total Funding Amount: Amendment Funding Date / Amount: April 2017-April 2022 Other Affected Units: Bureau for Food Security Lead BEO Bureau: Asia Prepared by: Alan Schroeder, PhD, MBA; Kim Hian Seng, PhD, with support from Abt Associates and iDE Date Prepared: 8/2/2018 ENVIRONMENTAL COMPLIANCE REVIEW DATA Analysis Type: §216.3(B) Pesticide Procedures - PERSUAP Environmental Determination: Negative Determination with Conditions PERSUAP Procedures Expiration Date: 12/31/2021 Climate Risks Considerations / Conditions 2018 Feed the Future Cambodia Harvest II PERSUAP 1 ACRONYMS AI Active Ingredient A/COR Agreement/Contracting Officer’s Representative ASIA Bureau for Asia BEO Bureau Environmental Officer BMP Best Management Practice BRC British Retail Consortium BT Bacillus thuringiensis -

Bacterial Communities of Herbivores and Pollinators That Have Co-Evolved Cucurbita Spp

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/691378; this version posted July 3, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 2 Bacterial communities of herbivores and pollinators that have co-evolved Cucurbita spp. 3 4 5 Lori R. Shapiro1, 2, Madison Youngblom3, Erin D. Scully4, Jorge Rocha5, Joseph Nathaniel 6 Paulson6, Vanja Klepac-Ceraj7, Angélica Cibrián-Jaramillo8, Margarita M. López-Uribe9 7 8 1 Department of Applied Ecology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 27695 USA 9 2 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, 10 USA 02138 11 3 Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 12 Madison WI, 53706 USA 13 4 Center for Grain and Animal Health Research, Stored Product Insect and Engineering Research 14 Unit, USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Manhattan, KS, 66502 USA 15 5 Conacyt-Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo en Agrobiotecnología Alimentaria, San Agustin 16 Tlaxiaca, Mexico 42162 17 6 Department of Biostatistics, Product Development, Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, 18 California 94102 19 7 Department of Biological Sciences, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA 02481 USA 16803 20 8 Laboratorio Nacional de Genómica para la Biodiversidad, Centro de Investigación y de 21 Estudios Avanzados del IPN, Irapuato, Mexico 36284 22 9 Department of Entomology, Center for Pollinator Research, Pennsylvania State University, 23 University Park, PA 24 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/691378; this version posted July 3, 2019.