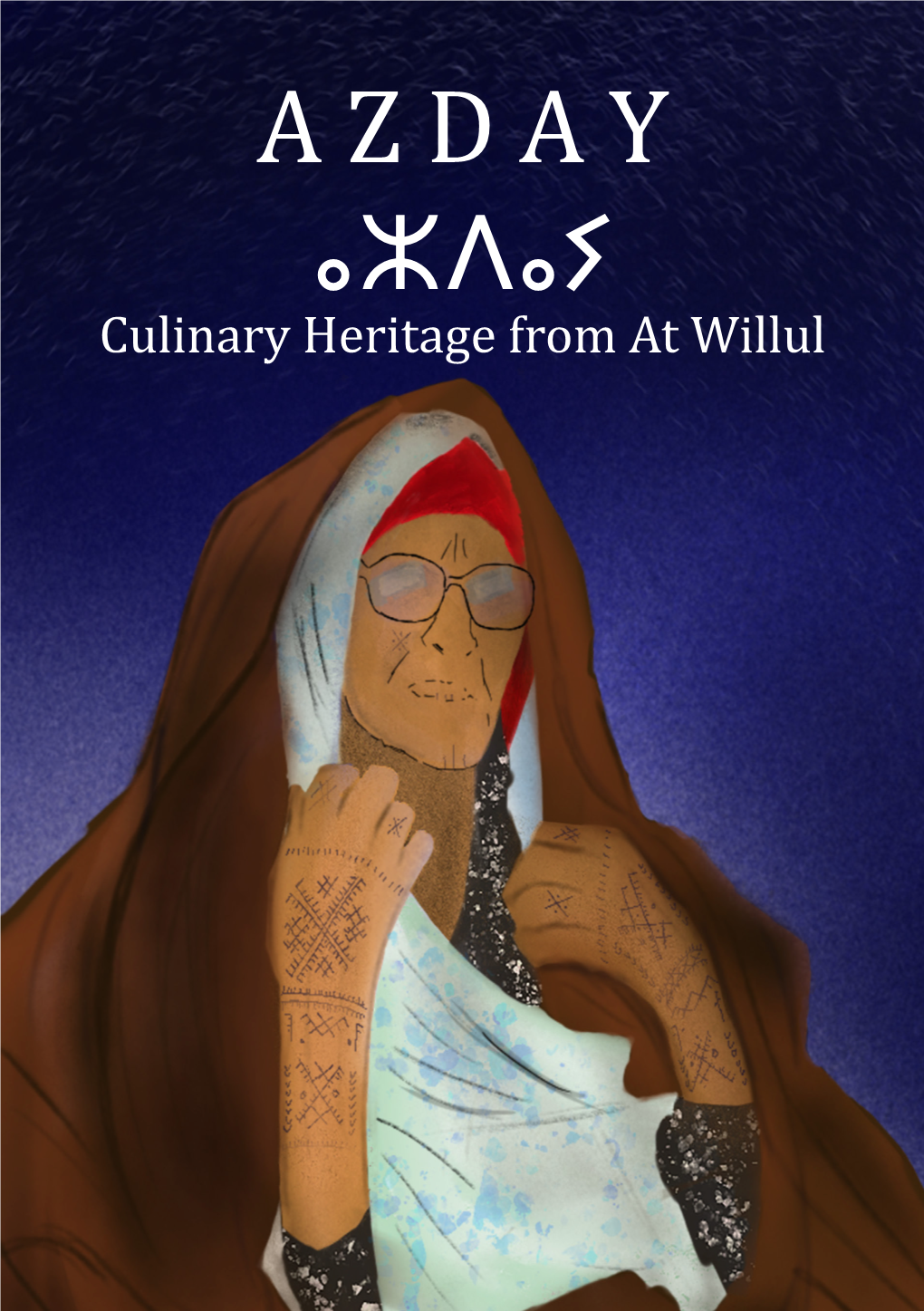

A Z D a Y ⴰⵣⴷⴰⵢ Culinary Heritage from at Willul 2 Dedication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pearl Couscous with Roasted Pumpkin and Chorizo (Serves 4)

Pearl couscous with roasted pumpkin and chorizo (serves 4) Ingredients: 500g pumpkin, peeled, seeded and cut in to 1cm cubes 2 large zucchini 225 g pearl couscous 1 chorizo, thinly sliced (125g) ½ cup chopped fresh coriander ¼ cup lemon juice 1 teaspoon smoked paprika 1 tablespoon olive oil Modifications 1 punnet cherry tomatoes (prick these with a knife and add them to the tray) 1 medium eggplant, cubed to 1cm pieces and added to tray for baking Method: Preheat oven to 200C. Line a baking tray with baking paper. Spread the pumpkin, zucchini, tomatoes and eggplant on the tray. Spray with oil and season with pepper Cook couscous in saucepan of boiling water for 10mins or until tender. Drain. Heat a non-stick frying pan over medium-high heat and stir chorizo for 3-5mins or until golden. Combine couscous, baked vegetables, chorizo and coriander in a large bowl. Whisk the lemon juice, oil and paprika in a jug and add to the bowl and stir. Sprinkle with some baby spinach. About this recipe: - Pearl (also known as Israeli) couscous is a handy grain to try – couscous is a medium GI grain, pearl couscous is a low GI grain - Adding more vegetables adds fibre and flavour to the dish as well as adding more volume to the meal without increasing the energy to kilojoules greatly. Nutrition (per serve after modification) Energy: 1957kJ (468 calories), 59g carbohydrates, 7.3g fibre, 16g protein, 16g fat, 3g saturated fat, 342mg sodium. Sources: Calorie King Australia, NUTTAB Recipe adapted from: Australian Good Taste - February 2013 http://www.taste.com.au/recipes/32447/pearl+couscous+with+roasted+pumpkin+and+chorizo . -

CATERING MENU Table of Contents

CATERING MENU Table of Contents Canapes Menu ................................................................................................................................................ Canapes Packages ............................................................................................................................. 3 Cold Canapes ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Hot Canapes ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Fancy Canapes .................................................................................................................................... 6 Dessert Canapes .................................................................................................................................. 7 Buffet Menu ...................................................................................................................................................... Starters .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Salads ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Mains ............................................................................................................................................. 11-12 -

THE BASTARD of ISTANBUL Elif Shafak Copyright: 2007 Book Jacket: Twenty Years Later, Asya Kazanci Lives with Her Extended Family in Istanbul

THE BASTARD OF ISTANBUL Elif Shafak Copyright: 2007 Book Jacket: Twenty years later, Asya Kazanci lives with her extended family in Istanbul. Due to a mysterious family curse, all the Kazanci men die in their early forties, so it is a house of women, among them Asya’s beautiful, rebellious mother Zeliha, who runs a tattoo parlour; Banu, who has newly discovered herself as a clairvoyant; and Feride, a hypochondriac obsessed with impending disatstr. And when Asya’s Armenian-American cousin Armanoush comes to stay, long-hidden family secrets connected with Turkey’s turbulent past begin to emerge. Elif Shafak is one of Turkey’s most acclaimed and outspoken novelists. She was born in 1971 and is the author of six novels, most recently The Saint of Incipient Insanities, The Gaze and The Flea Palace, and one work of non-fiction. She teaches at the University of Arizona and divides her time between the US and Istanbul. TO EYUP and I)EHRAZAT ZELDA Once there was; once there wasn’t. God’s creatures were as plentiful as grains And talking too much was a sin…. -The preamble to a Turkish tale … and to an Armenian one ONE Cinnamon W hatever falls from the sky above, thou shall not curse it. That includes the rain. No matter what might pour down, no matter how heavy the cloudburst or how icy the sleet, you should never ever utter profanities against whatever the heavens might have in store for us. Everybody knows this. And that includes Zeliha. Yet, there she was on this first Friday ofJuly, walking on a sidewalk that flowed next to hopelessly clogged traffic; rushing to an appointment she was now late for, swearing like a trooper, hissing one profanity after another at the broken pavement stones, at her high heels, at the man stalking her, at each and every driver who honked frantically when it was an urban fact that clamor had no effect on unclogging traffic, at the whole Ottoman dynasty for once upon a time conquering the city of Constantinople, and then sticking by its mistake, and yes, at the rain … this damn summer rain. -

Steaming – an Outdated Method to Cook Tasteless 80'S Food Or the Definition of Trendy and Tasty Cooking?

“Steaming – an outdated method to cook tasteless 80’s food or the definition of trendy and tasty cooking?” When you hear the word “steam”, you probably think of the 80’s diets. Think again. The method is starting to find its way back into the fine restaurants and even into people’s homes. Tasteology is the name of a new AEG-initiated documentary series uncovering the four steps of how to achieve cooking results that are multisensory, sustainable, nutritional and tasteful all at once. The four-episode series invites viewers on a culinary journey around the world to gain inspiration and knowledge far beyond the usual TV cooking shows. Tasteology will be launched on May 25 and is then available on Youtube. Heating food might be one of the most central steps of cooking, and there are many ways to do so. Boling and frying is probably the most obvious methods but there are many more ways to bring heat to the process of cooking. Steaming is one of them, and has made a comeback. Today, steaming is very popular among top chefs around the world, and has even spread into people’s homes. However, steaming is not to be confused with the term ‘sous vide’ which has also become very popular among the super trendy and curious foodies who want to brag about vacuum sealing food before cooking it at a low temperature either in hot water or with steam. “When you sous vide you’re taking away all the air and the method allows you too cook at a low temperature, just like steaming. -

Instruction Manual Rice Cooker • Slow Cooker • Food Steamer Professional

ARC-3000SB Instruction Manual Rice Cooker • Slow Cooker • Food Steamer Professional Questions or concerns about your rice cooker? Before returning to the store... Aroma’s customer service experts are happy to help. Call us toll-free at 1-800-276-6286. Answers to many common questions and even replacement parts can be found online. Visit www.AromaCo.com/Support. Download your free digital recipe book at www.AromaCo.com/3000SBRecipes Download your free digital recipe book at www.AromaCo.com/3000SBRecipes Congratulations on your purchase of the Aroma® Professional™ 20-Cup Digital Rice Cooker, Food Steamer and Slow Cooker. In no time at all, you’ll be making fantastic, restaurant-quality rice at the touch of a button! Whether long, medium or short grain, this cooker is specially calibrated to prepare all varieties of rice, including tough-to-cook whole grain brown rice, to fluffy perfection. In addition to rice, your new Aroma® Professional™ Rice Cooker is ideal for healthy, one-pot meals for the whole family. The convenient steam tray inserts directly over the rice, allowing you to cook moist, fresh meats and vegetables at the same time, in the same pot. Steaming foods locks in their natural flavor and nutrients without added oil or fat, for meals that are as nutritious and low-calorie as they are easy. Aroma®’s Sauté-Then-Simmer™ Technology is ideal for the easy preparation of Spanish rice, risottos, pilafs, packaged meal helpers, stir frys and more stovetop favorites! And the new Slow Cook function adds an extra dimension of versatility to your rice cooker, allowing it to fully function as a programmable slow cooker! Use them together for simplified searing and slow cooking in the same pot. -

Steaming of Dried Produce 2018

Steaming of dried produce: Guidance to minimize the microbiological risk 1 Table of contents Purpose of this booklet 3 Purpose of this booklet Content overview Microbiological food safety for Content overview This booklet helps you to understand steaming of dried produce Microbiological food safety for steaming of dried produce and manage the critical elements that Dried produce (e.g. herbs, spices, (root) 5 Field of application: Dried produce and steaming impact microbiological food safety vegetables, fruits) can be contaminated 6 Steaming during steaming of dried produce. with pathogenic microorganisms Process overview • Why is it important to manage the that survive the drying process or Management of the process steaming properly; contaminate the product at a later stage 8 Best processing practices • What are the main elements to in the supply chain. 9 Maintenance of equipment control during steaming of dried 1 0 Validation produce; For some dried produce categories, Why is validation so important? • What are the main elements to steaming is a frequently applied Microbiological validation study manage for an effective maintenance thermal process to control Microbiological reduction targets of equipment; microbiological hazards (see Examples of safe processing reference conditions • Why is it important to validate and decision tree on page 6 in booklet Steaming of fresh produce (blanching) verify the microbial reduction for a “Drying of produce: Guidance to 1 2 Verification steaming process. minimize the microbiological risk”)*. Why is verification so important? 13 Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) On dried produce, pathogenic Why is it important to have GMPs in place? microorganisms do not grow but can Zoning survive and maintain pathogenicity Cleaning for several months or even years. -

Barbecue Food Safety

United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service Food Safety Information PhotoDisc Barbecue and Food Safety ooking outdoors was once only a summer activity shared with family and friends. Now more than half of CAmericans say they are cooking outdoors year round. So whether the snow is blowing or the sun is shining brightly, it’s important to follow food safety guidelines to prevent harmful bacteria from multiplying and causing foodborne illness. Use these simple guidelines for grilling food safely. From the Store: Home First However, if the marinade used on raw meat or poultry is to be reused, make sure to let it come to a When shopping, buy cold food like meat and poultry boil first to destroy any harmful bacteria. last, right before checkout. Separate raw meat and poultry from other food in your shopping cart. To Transporting guard against cross-contamination — which can happen when raw meat or poultry juices drip on When carrying food to another location, keep it cold other food — put packages of raw meat and poultry to minimize bacterial growth. Use an insulated cooler into plastic bags. with sufficient ice or ice packs to keep the food at 40 °F or below. Pack food right from the refrigerator Plan to drive directly home from the grocery store. into the cooler immediately before leaving home. You may want to take a cooler with ice for perishables. Always refrigerate perishable food Keep Cold Food Cold within 2 hours. Refrigerate within 1 hour when the temperature is above 90 °F. Keep meat and poultry refrigerated until ready to use. -

Eat Smart II

COACH Heart Manual Reading Food Labels CALORIES § Calories are a unit of energy § Women need an average of 1800 – 2000 calories per day. § Men need an average of 2200 – 2400 calories per day. § Did you know? 1 gram of fat has 9 calories, and 1 gram of carbohydrate or protein has 4 calories TOTAL FAT § High intake of certain fats (see below) fat may contribute to heart disease and cancer. § Most women should aim for 40 – 65 g fat/day and men 60 – 90g/day. § For a healthy heart, choose foods with a low amount of saturated and trans fat. § Unsaturated (heart healthier fats are not always listed) SATURATED + TRANS FAT SERVING SIZE § Saturated fat and trans fats are a part of § Is your serving the same size as the the total fat in food - they are listed one on the label? separately because they are the key § If you eat double the serving size players in raising blood cholesterol listed, you need to double the nutrients and your risk of heart disease. and calorie values. § It’s recommended to limit your total intake to no more than 20 grams a day of saturated and trans fat combined. DAILY VALUE § The Daily Value (or DV) lists the CHOLESTEROL amount (%) fat, sodium, and other § Too much cholesterol – a second nutrients a product contains based on a cousin to fat – can lead to heart 2000 calorie diet. This may be more disease. or less than what you eat. § Challenge yourself to eat less than 300 § Use % DV to see if a food has a little mg each day (1 egg =186 mg) or a lot of a nutrient. -

Vegetable Steaming 101

Vegetable Steaming 101 Steaming vegetables is one of the easiest & quickest ways to get vegetables at each meal. It’s time to ditch the mushy boiled veggies and expensive steamer bags. Learn this simple cooking technique and start steaming your own fresh vitaminpacked veggies! Did you know: ● The longer you cook veggies, the more nutrients are lost. Unlike boiled vegetables, steamed veggies are cooked briefly and then removed from the heat. ● The goal of steaming is to cook the vegetables until they are no longer raw, but still bright and crisp. This preserves color and flavor, and some of the nutrient content. ● Frozen veggies work great in the steamer, so keep a bag of frozen veggies on hand for those days you can’t make it to the grocery store! Quick Start Guide A steaming pot usually looks something like this: Steamerpot set Stainless steel steamer basket 3tier steamerpot set Steaming HowTo: 1. Place an inch and a half of water 2. Put your vegetables into the 3.Cook for 510 min with the lid into a pot, and heat to boiling. steamer basket and place the lid on. on. Poke with a fork to check doneness. (cooking times vary. See chart below for recommended cooking times) The Table below lists a number of vegetables, their recommended cooking times as well as seasoning ideas. Now, get steaming! Vegetable Size/Preparation Cooking How to season Time Artichokes Steam whole artichokes 2540 min Season with extra virgin olive oil and lemon zest Asparagus Whole spears, thick spears peeled lightly 713 min Serve with olive oil combined with -

Food Steamer Olla Para Cocinar a Vapor

FOOD STEAMER OLLA PARA COCINAR A VAPOR User Guide/ Guía del Usuario: Safety For product questions contact: Seguridad Jarden Consumer Service USA : 1.800.334.0759 Canada : 1.800.667.8623 www.oster.com How to use Cómo usar ©2010 Sunbeam Products, Inc. doing business as Jarden Consumer Solutions. All rights reserved. Distributed by Sunbeam Products, Inc. doing business as Jarden Consumer Solutions, Boca Raton, Florida 33431. Cleaning Para preguntas sobre los productos llame: Cuidado y Limpieza Jarden Consumer Service EE.UU.: 1.800.334.0759 Canadá : 1.800.667.8623 www.oster.com Recipes ©2010 Sunbeam Products, Inc. operando bajo el nombre de Recetas Jarden Consumer Solutions. Todos los derechos reservados. Distribuido por Sunbeam Products, Inc. operando bajo el nombre de Jarden Consumer Solutions, Boca Raton, Florida 33431. Warranty SPR-110510-750REVA P.N. 146396Rev.A Garantía Printed in China Impreso en China www.oster.com This appliance has a polarized alternating current plug (one blade IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS is wider than the other). To reduce the risk of electric shock, as a When using electrical appliances, basic safety precautions safety feature, this plug will fit in a polarized outlet only one way. If should always be followed, including the following: the plug does not insert fully in the outlet, reverse the plug. If it still 1. Read all instructions before using. fails to fit, contact a qualified electrician. 2. Do not touch hot surfaces. Use potholders when removing DO NOT ATTEMPT TO DEFEAT THIS SAFETY FEATURE. cover or handling hot containers to avoid steam burns. Lift and open cover carefully to avoid scalding and allow water to drip into steamer. -

Food Steamer Cooking Guide

Steamer Features Stainless steel construction ES5 Series Top Loading EmberGlo® Steamers Self Contained or Direct Water Supply – Secrets for Great Tasting Food – Removable Water Pan Tap Water Operation Pump, Push-button or Timed Steam cooking is one of the healthiest and quickest ways to ES10 Series Full Sized Food Pan cook vegetables while locking Auto Timer or Optional Push-button in nutrients and intensifying Direct Connect to Tap Water Supply the fl avors. It leaves more of Quick Connect ES 10 the vegetables’ natural taste, Full Pan AR Series Front Opening - Self Contained Water texture and color intact than any other method of Supply (Distilled Water ONLY) cooking including microwav- 1/2 or 2/3 Food Pan ing; it seals in more vitamins Food Steamer Accessories for Steamers and minerals than if you would Increase your effi ciency with accessories have boiled or baked them; Cooking Guide made just for your steamers. and it requires no added fat. Steaming Basket Sets and Steaming Racks: Steaming is the ideal solution Take full advantage of your ES 5 Half Pan for crisp, compact vegetables EmberGlo Steamer with specially designed stainless (potatoes,caulifl ower, sweet corn More than a steel Steaming Basket Sets etc.) and some varieties of lean meat and fi sh. Th e and Steaming Racks. All sets Half Pan Size Basket - 5608-72 nutritional benefi ts you can off er your customers Bun Warmer . and racks come with an easy Quarter Pan Size Basket (2 pk) - 5608-73 to use removable handle. 3 in One Basket Set (1 Half and 2 Quarters) with the advantages of cooking with this ancient - 5608-70 (Basket Sets come with a Handle) Increase your effi ciency by technique in the contemporary kitchen are obvious, dual steaming diff erent items in separate baskets. -

Cultural Identity Construction in Russian-Jewish Post-Immigration Literature

Cultural Identity Construction in Russian-Jewish Post-Immigration Literature by Regan Cathryn Treewater A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature University of Alberta © Regan Cathryn Treewater, 2017 ii Abstract The following dissertation examines narratives of immigration to Western Europe, Israel and North America authored by Russian-speaking writers of Jewish decent, born in the Soviet Union after World War II. The project seeks to investigate representations of resettlement experiences and cultural identity construction in the literature of the post- 1970s Russian-Jewish diaspora. The seven authors whose selected works comprise the corpus of analysis write in Russian, German and English, reflecting the complex performative nature of their own multilayered identities. The authors included are Dina Rubina, Liudmila Ulitskaia, Wladimir Kaminer, Lara Vapnyar, Gary Shteyngart, Irina Reyn, and David Bezmozgis. The corpus is a selection of fictional and semi- autobiographical narratives that focus on cultural displacement and the subsequent renegotiation of ‘self’ following immigration. In the 1970s and final years of Communist rule, over one million Soviet citizens of Jewish heritage immigrated to Western Europe, Israel and North America. Inhospitable government policies towards Soviet citizens identified as Jewish and social traditions of anti-Semitism precipitated this mass exodus. After escaping prejudice within the Soviet system, these Jewish immigrants were marginalized in their adopted homelands as Russians. The following study of displacement and relocation draws on Homi Bhabha’s theories of othering and unhomeliness. The analyzed works demonstrate both culturally based othering and unhomely experiences pre- and post-immigration resulting from relegation to the periphery of society.