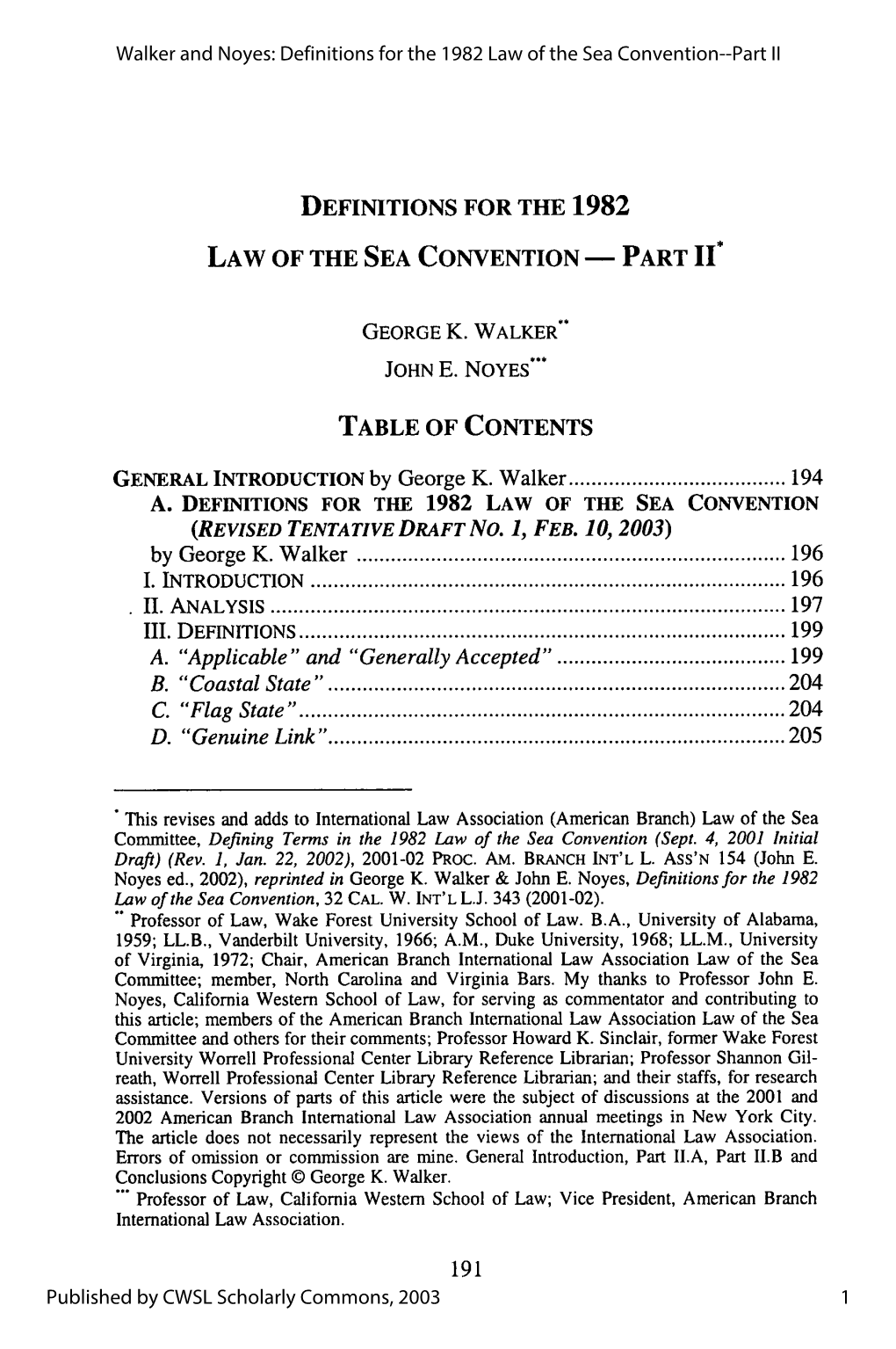

Definitions for the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention--Part II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directions for a Middle East Settlement—Some Underlying

DIRECTIONS FOR A MIDDLE EAST SETTLEMENT- SOME UNDERLYING LEGAL PROBLEMS SHABTAI ROSENNE* I INTRODUCTION A. Legal Framework of Arab-Israeli Relations The invitation to me to participate in this symposium suggested devoting attention primarily to the legal aspects and not to the facts. Yet there is great value in the civil law maxim: Narra mihi facta, narabo tibi jus. Law does not operate in a vacuum or in the abstract, but only in the closest contact with facts; and the merit of legal exposition depends directly upon its relationship with the facts. It is a fact that as part of its approach to the settlement of the current crisis, the Government of Israel is insistent that whatever solution is reached should be em- bodied in a secure legal regime of a contractual character directly binding on all the states concerned. International law in general, and the underlying international legal aspects of the crisis of the Middle East, are no exceptions to this legal approach which integrates law with the facts. But faced with the multitude of facts arrayed by one protagonist or another, sometimes facts going back to the remotest periods of prehistory, the first task of the lawyer is to separate the wheat from the chaff, to place first things first and last things last, and to discipline himself to the most rigorous standards of relevance that contemporary legal science imposes. The authority of the Interna- tional Court itself exists for this approach: the irony with which in I953 that august tribunal brushed off historical arguments, in that instance only going back to the early feudal period, will not be lost on the perceptive reader of international juris- prudence.' Another fundamental question which must be indicated at the outset relates to the very character of the legal framework within which the political issues are to be discussed and placed. -

Shabtai Rosenne and the International Court of Justice*

The Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals 12 (2013) 163–175 brill.com/lape Shabtai Rosenne and the International Court of Justice* Dame Rosalyn Higgins DBE QC Former President of the International Court of Justice It is by now well known in the world of international law that a new Judge at the International Court of Justice finds awaiting him or her on the office bookshelf not only the Pleadings, Judgments and Opinions of the Perma- nent Court of Justice and of the International Court of Justice, but the four volumes of Shabtai Rosenne’s The Law and Practice of the International Court, 1920–2005. Of course, there have over the years been many well-respected and knowledgeable writers on the Court. But the question arises: how could it be, that one who was never (for various reasons unrelated to his ability) a Judge of the International Court, produced thousands of pages, so full of insight and understanding, and precise in their formulation, that they have come to be regarded as somehow determinative of issues that arose in the life of the Court? These volumes were a marvel, yes, but how could they be so, especially as they were written by an author who had not ‘lived within the Court’? The answer is twofold: first, Shabtai Rosenne was a great, great man and scholar. Second, for nearly sixty years he had an ‘inside track’ at the Court. And he had it because he noted, he saw, he compared, and he asked, asked, and asked again – seeking information and explanations from seven Regis- trars. -

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Daphna Shraga * and Ralph Zacklin ** I. Introduction The key to an. understanding of the Statute of the International Tribunal for the prosecution of persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia (hereinafter International Tribunal or Tribunal) is the context within which the Security Council took its decision of principle to establish it1 By the end of February 1993 the conflict in the former Yugoslavia had been underway for more than 18 months, the principal focus of the conflict shifting from Slovenia to Croatia and then to Bosnia. United Nations involvement, through UNPROFOR, which at its inception had been conceived of as a protection force to shield pockets of Serbs in a newly independent Croatia (the United Nations Protected Areas) had gradually evolved into a multi-dimensional peace-keeping force whose main activities then centred on Bosnia. The character of the conflict had also evolved. While from the very beginning great brutality had marked the conduct of the parties, it was in Bosnia that the first signs of international crimes began to emerge: mass executions, mass sexual assaults and rapes, the existence of concentration camps and the implementation of a policy of so-called 'ethnic cleansing'. The Security Council repeatedly enjoined the parties to observe and comply with their obligations under international humanitarian law but the parties systematically ignored such injunctions. In October 1992 the Security Council, unable to control the wilful disregard by the parties for international norms, sought to create a dissuasive effect by asking the Secretary-General to establish a * Legal Officer, General Legal Division, Office of Legal Affairs, United Nations. -

Sovereignty Over Land and Sea in the Arctic Area

Agenda Internacional Año XXIII N° 34, 2016, pp. 169-196 ISSN 1027-6750 Sovereignty over Land and Sea in the Arctic Area Tullio Scovazzi* Abstract The paper reviews the claims over land and waters in the Arctic area. While almost all the disputes over land have today been settled, several questions relating to law of the sea are still pending. They regard straight baselines, navigation in ice-covered areas, transit through inter- national straits, the outer limit of the continental shelf beyond 200 n.m. and delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between opposite or adjacent States. Keywords: straight baselines, navigation in ice-covered areas, transit passage in international straits, external limit of the continental shelf, exclusive economic zone La soberanía sobre tierra y mar en el área ártica Resumen El artículo examina los reclamos sobre el suelo y las aguas en el Ártico. Mientras que casi todas las disputas sobre el suelo han sido resueltas al día de hoy, aún quedan pendientes muchas cuestiones relativas al derecho del mar. Ellas están referidas a las líneas de base rectas, la navegación en las zonas cubiertas de hielo, el paso en tránsito en estrechos internacionales, el límite externo de la plataforma continental más allá de las 200 millas náu- ticas, y la delimitación de la zona económica exclusiva entre Estados adyacentes u opuestos. Palabras clave: Líneas de base rectas, navegación en zonas cubiertas de hielo, paso en tránsito en los estrechos internacionales, límite externo de la plataforma continental, zona económica exclusiva. * Professor of International Law, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy. -

Professor Shabtai Rosenne (1917-2010) Possessed of a Powerful Personality and a Towering Intellect, Shabtai Rosenne Bestrode Two Worlds

Professor Shabtai Rosenne (1917-2010) Possessed of a powerful personality and a towering intellect, Shabtai Rosenne bestrode two worlds. As an Israeli diplomat, he helped shape the institutions of gov- ernment from pre-state days and remained a person of consequence to his last days. As an international lawyer, his contributions were vast, infl uential and unmatched. He has been described as one of the foremost international lawyers of the second half of the twentieth century. He mixed encyclopaedic knowledge of the law with a profound understanding of practice. He was the preeminent well-rounded interna- tional lawyer. He died aged 92 on 21 September 2010. Rosenne’s inspiration, as his speech accepting the highly prestigious Hague Prize for International Law in 2004 underlined time and again, was the Biblical instruc- tion demanding that “justice, justice shalt thou pursue”. He, typically, devoted that speech to the place of international law in the daily life of the average human being. Proud of his Jewish heritage and extraordinarily knowledgeable about it, Rosenne became the supreme international law universalist. His quest for knowledge was insatiable and he formed, for example, a close friendship with Judge Nagendra Singh of the International Court of Justice, based not least upon a shared love of Hindu philosophy. His writings on that Court, including a four volume colossus, made him the foremost authority on its law and practice and it is well known that generations of judges consulted him quietly on diffi cult questions. He would undoubtedly have been elected a judge had it not been for the political constellation of those years. -

UNIVERSIDAD DE GINEBRA LAS OPINIONES CONSULTIVAS DE LA CORTE DE LA HAYA Évolución Y Aspectos Recientes

UNIVERSIDAD DE GINEBRA INSTITUTO UNIVERSITARIO DE ALTOS ÉSTUDIOS INTERNACIONALES LAS OPINIONES CONSULTIVAS DE LA CORTE DE LA HAYA Évolución y aspectos recientes -Análisis doctrinal y jurisprudencial- TESIS presentada para la obtención del posgrado Diploma de Estudios Superiores en Relaciones Internacionales - DES (Mención Derecho Internacional) por Gustavo OLIVARES (PERÚ) Enero de 1992 ABREVIACIONES Y SIGLAS Colecciones y periódicos ABA J. American Bar Association Journal. AFDI Annuaire Français de droit international. Annuaire CDI / YILC Annuaire de la Commission du droit international / Yearbook of the International Law Commission. Annuaire IDI Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. AJIL American Journal of International Law. ASIL American Society of International Law. BYBIL British Year Book of International Law. BzaöRV Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht. Calif. L. Rev. California Law Review. Colum. J. Transnat'l L. Columbia Journal of Transnational Law. Colum. L. Rev. Columbia Law Review. Den. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y. Denver Journal of International Law and Policy. Ency. PIL Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Harvard ILJ Harvard International Law Journal. Harv. L. Rev. Harvard Law Review. Indian JIL Indian Journal of International Law. Int'l & Comp. LQ The International & Comparative Law Quarterly. Juris-Classeur Juris-Classeur de droit international. LGDJ Librairie générale de droit et de jurisprudence. Misc. Pamphlets Miscellaneous Pamphlets on the PCIJ. RBDI Revue Belge de droit international. RDILC Revue de droit international et de législation comparée. RDI sci. dipl. pol. Revue de droit international de sciences diplomatiques et politiques. RCADI Recueil des cours de l'Académie de droit international. REDI Revista Española de Derecho Internacional. RGDIP Revue générale de droit international public. -

THE HAGUE La HAYE No 2 COMPTE BERDU

International Court Cour internationale of Justice de Justice THE HAGUE La HAYE Public sitting held on Thursday 26 August 1993, at 3 p.=., at the Peace Palace, President Sir Robert Jennings presiding in the case concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crie of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro)) Requests for the Indication of Provisional Measures No 2 - VEFLBATIM RECORD Audience publique tenue le jeudi 26 août 1993, à 15 heures, au Palais de la Paix, saus la présidence de sir Robert Jennings, Président en I'affaire relative à l'Application de 1s convention pour la prhvention et la répression d~ crime de génocide (Bosnie-Herzégovine c. Yougoslavie (Serbie et ~onténégro)) Demandes en indication de mesures conservatoires no 2 COMPTE BERDU Present : President Sir Robert Jennings Vice-President Oda Judges Schwebel Bed jaoui Ni Evens en Tarassov Guillaume Shahabuddeen Aguilar Mawdsley Weeramantry Ajibola Herczegh Judges ad hoc Lauterpacht Kreca Registrar Valencia-Ospina présents: Sir Robert Jennings, Président M. Oda, Vice-Président MM. Schwebel Bedjaoui Ni Evensen Tarassov Guillaume Shahabuddeen Aguilar Mawdsley Weeramantry Ajibola, juges Herczegh, juges Lauterpacht, Kreca, juges ad hoc M. Valencia-Ospina, Greffier The Govexnment of the Regublic of Bosnia and Herzegovina is represented by: : H. E. Mr. Muhamed Sacirbey, Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the United Nations; Mr. Francis A. Boyle, Professor of International Law, as Agent ; Mr. Phon van den Biesen, Advocate, Mr. Khawar Qureshi, Barrister, England, as Advocates and Counsel; Mr. Marc Weller, Assistant Lecturer in Law, University of Cambridge, Senior Research Fellow of St. -

25Th Anniversary Commemoration the Gulf of Maine Maritime Boundary Delimitation: the Constitution of the Chamber, 15 Ocean & Coastal L.J

Ocean and Coastal Law Journal Volume 15 | Number 2 Article 4 2010 25th Anniversary Commemoration The ulG f Of Maine Maritime Boundary Delimitation: The Constitution Of The hC amber Judge Stephen M. Schwebel Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/oclj Recommended Citation Judge Stephen M. Schwebel, 25th Anniversary Commemoration The Gulf Of Maine Maritime Boundary Delimitation: The Constitution Of The Chamber, 15 Ocean & Coastal L.J. (2010). Available at: http://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/oclj/vol15/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ocean and Coastal Law Journal by an authorized administrator of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 25TH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION THE GULF OF MAINE MARITIME BOUNDARY DELIMITATION: THE CONSTITUTION OF THE CHAMBER Judge Stephen M. Schwebel* Judgment in the Case Concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Gulf of Maine Area (Gulf of Maine Case) was rendered not by the plenary International Court of Justice (ICJ) but, pursuant to Article 26 of its founding statute, by “a chamber for dealing with a particular case.”1 Provision for that type of Chamber was not found in the statute of the Court’s predecessor, the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ).2 One of the few changes in the Permanent Court’s statute made in 1945 when the Statute of the International Court of Justice was adopted as an annex to the United Nations Charter was to add a provision for such particular, ad hoc Chambers.3 A significant subtraction was made in 1945 as well. -

Bibliography of Professor Shabtai Rosenne (Compiled by Mr

Bibliography of Professor Shabtai Rosenne (Compiled by Mr. Hans Thijssen, with the kind permission and assistance of the Peace Palace Library) ‘Capacity to Litigate in the International Court of Justice: Refl ections on Yugoslavia in the Court’, 80 British Yearbook of International Law (2009) pp. 217-243. ‘Self-defence and the Non-use of Force: Some Random Th oughts’, in Arthur Eyffi n- ger, Alan Stephens et al. (eds.), Self-defence as a Fundamental Principle, Th e Hague: Hague Academic Press 2009, pp. 49-65. ‘Th e International Court of Justice: New Practice Directions’, 8 Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals (2009) pp. 171-180. ‘Refl ections on Fisheries Management Disputes’, in Rafael Casado Raigón et Giuseppe Cataldi (eds.), L’évolution et l’état actuel du droit international de la mer: mélanges de droit de la mer off erts à Daniel Vignes, Bruxelles: Bruylant 2009, pp. 829-851. ‘Th e International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice: Some Points of Contact’, in José Doria et al. (eds.), Th e Legal Regime of the Interna- tional Criminal Court: Essays in honour of professor Igor Blishchenko: In Memo- riam Professor Igor Pavlovich Blishchenko (1930-2000), Leiden: Nijhoff 2009, pp. 1003-1012. ‘Acceptance Speech by Professor Shabtai Rosenne on Receiving the First Hague Prize for International Law 2004’, in David Vriesendorp et al. (eds.), Th e Hague Legal Capital?: Liber in Honorem W.J. Deetman, Th e Hague: Hague Academic Press 2008, pp. 105-116. ‘Arbitrations under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea’, in Tafsir Malick Ndiaye and Rüdiger Wolfrum (eds.), Law of the sea, environ- mental law and settlement of disputes: Liber amicorum judge Th omas A. -

Shabtai Rosenne (24 November 1917–21 September 2010) a Personal Reflection

The Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals 9 (2010) 405–407 brill.nl/lape Shabtai Rosenne (24 November 1917–21 September 2010) A Personal Reflection For more than fifty years, Shabtai Rosenne came to the Netherlands to have his manuscripts published by Sijthoff and Nijhoff, respectively. In this endeavour he was assisted by quite a number of different publishers, among them Ronald M. Goodman and Alan D. Stephens. I had the great privilege to work with Shabtai as (one of) his publisher(s) from 1987 until 2006 and like so many of us, I continued my friendship with Shabtai until his death on 21 September 2010. One of my first encounters with Shabtai was when he visited the pub- lishers’ offices in Dordrecht. We were instructed in advance to be witty and entertaining during our “brown bag luncheon”, but we were all a bit intim- idated. This was not at all necessary, the lunch was very animated and Shabtai entertained us all. One of my first tasks at Nijhoff was the publication ofInternational Law at a Time of Perplexity: Essays in Honour of Shabtai Rosenne, edited by Pro- fessor Yoram Dinstein and Dr Mala Tabory. It was published on the occa- sion of Shabtai’s seventieth birthday and contains fifty-five contributions by eminent scholars and practitioners in the field of international law. It was also one of the first publications of which the manuscript was prepared through a “desktop” in-house publishing process. It was an experiment, but the experiment involved fifty-five demanding authors, which was not an easy task. -

Non-Corrigé Uncorrected

Non-Corrigé Uncorrected CR 2007/16 International Court Cour internationale of Justice de Justice THE HAGUE LA HAYE YEAR 2007 Public sitting held on Monday 4 June 2007, at 10.10 a.m., at the Peace Palace, President Higgins presiding, in the case concerning the Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia) ________________ VERBATIM RECORD ________________ ANNÉE 2007 Audience publique tenue le lundi 4 juin 2007, à 10 h 10, au Palais de la Paix, sous la présidence de Mme Higgins, président, en l’affaire du Différend territorial et maritime (Nicaragua c. Colombie) ____________________ COMPTE RENDU ____________________ - 2 - Present: President Higgins Vice-President Al-Khasawneh Judges Ranjeva Shi Koroma Parra-Aranguren Buergenthal Owada Simma Tomka Abraham Keith Sepúlveda-Amor Bennouna Skotnikov Judges ad hoc Fortier Gaja Registrar Couvreur ⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯ - 3 - Présents : Mme Higgins, président M. Al-Khasawneh, vice-président MM. Ranjeva Shi Koroma Parra-Aranguren Buergenthal Owada Simma Tomka Abraham Keith Sepúlveda-Amor Bennouna Skotnikov, juges MM. Fortier Gaja, juges ad hoc M. Couvreur, greffier ⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯ - 4 - The Government of Nicaragua is represented by: H.E. Mr. Carlos José Argüello Gómez, Ambassador of the Republic of Nicaragua to the Kingdom of the Netherlands, as Agent and Counsel; Mr. Ian Brownlie, C.B.E., Q.C., F.B.A., member of the English Bar, Chairman of the International Law Commission, Emeritus Chichele Professor of Public International Law, University of Oxford, member of the Institut de droit international, Distinguished Fellow, All Souls College, Oxford, Mr. Alex Oude Elferink, Research Associate, Netherlands Institute for the Law of the Sea, Utrecht University, Mr. Alain Pellet, Professor at the University Paris X-Nanterre, Member and former Chairman of the International Law Commission, Mr. -

History of Honors Conferred by the American Society of International

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Regulation on the Honors Committee The Honors Committee shall make recommendations to the Executive Council with respect to the Society’s three annual awards: the Manley O. Hudson Medal, given to a distinguished person of American or other nationality for outstanding contributions to scholarship and achievement in international law; the Goler T. Butcher Medal, given to a distinguished person of American or other nationality for outstanding contributions to the development or effective realization of international human rights law; and the Honorary Member Award, given to a person of American or other nationality who has rendered distinguished contributions or service in the field of international law. (Note: Until 2015, the award was permitted to be given only to a non-American) RECIPIENTS OF THE MANLEY O. HUDSON MEDAL (†Deceased) 1956 Manley O. Hudson† 1989 Not awarded 1957 Not awarded 1990 Not awarded 1958 Not awarded 1991 Not awarded 1959 Lord McNair† 1992 Not awarded 1960 Not awarded 1993 Sir Robert Y. Jennings† 1961 Not awarded 1994 Not awarded 1962 Not awarded 1995 Louis Henkin† 1963 Not awarded 1996 Louis B. Sohn† 1964 Philip C. Jessup† 1997 John R. Stevenson† 1965 Not awarded 1998 Rosalyn Higgins 1966 Charles De Visscher† 1999 Shabtai Rosenne† 1967 Not awarded 2000 Stephen M. Schwebel 1968 Not awarded 2001 Prosper Weil† 1969 Not awarded 2002 Thomas Buergenthal 1970 Paul Guggenheim† 2003 Thomas M. Franck† 1971 Not awarded 2004 W. Michael Reisman 1972 Not awarded 2005 Elihu Lauterpacht† 1973 Not awarded 2006 Theodor Meron 1974 Not awarded 2007 Andreas Lowenfeld† 1975 Not awarded 2008 John Jackson† 1976 Myres McDougal† 2009 Charles N.