The Gaza Flotilla Attack and Its Aftermath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 459.71 Kb

מרכז המידע הישראלי לזכויות האדם בשטחים (ע.ר.) One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 Researched and written by Yehezkel Lein Data coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Ariana Baruch, Rim ‘Odeh, Shlomi Swissa Fieldwork by Musa Abu Hashhash, Iyad Haddad, Zaki Kahil, Karim Jubran, Mazen al-Majdalawi, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi Assistance on legal issues by Yossi Wolfson Translated by Zvi Shulman, Shaul Vardi Edited by Rachel Greenspahn Introduction “The only thing missing in Gaza is a morning line-up,” said Abu Majid, who spent ten years in Israeli prisons, to Israeli journalist Amira Hass in 1996.1 This sarcastic comment expressed the frustration of Gaza residents that results from Israel’s rigid policy of closure on the Gaza Strip following the signing of the Oslo Agreements. The gap between the metaphor of the Gaza Strip as a prison and the reality in which Gazans live has rapidly shrunk since the outbreak of the intifada in September 2000 and the imposition of even harsher restrictions on movement. The shrinking of this gap is the subject of this report. Israel’s current policy on access into and out of the Gaza Strip developed gradually during the 1990s. The main component is the “general closure” that was imposed in 1993 on the Occupied Territories and has remained in effect ever since. Every Palestinian wanting to enter Israel, including those wanting to travel between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, needs an individual permit. In 1995, about the time of the Israeli military’s redeployment in the Gaza Strip pursuant to the Oslo Agreements, Israel built a perimeter fence, encircling the Gaza Strip and separating it from Israel. -

Future Notes

No. 3, November 2016 FUTURE NOTES ENERGY RELATIONS BETWEEN TURKEY AND ISRAEL Aybars Görgülü and Sabiha Senyücel Gündoğar This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement No 693244 Middle East and North Africa Regional Architecture: Mapping Geopolitical Shifts, regional Order and Domestic Transformations FUTURE NOTES No. 3, November2016 ENERGY RELATIONS BETWEEN TURKEY AND ISRAEL Aybars Görgülü and Sabiha Senyücel Gündoğar1 After six years of détente, on June 2016 Israel and Turkey finally reached a deal to normalize diplomatic relations and signed a reconciliation agreement. Israel-Turkey relations had already been broken after Israel’s offensive in Gaza between December 2008 and January 2009. Turkey voiced strong disapproval of this attack, which killed more than a thousand civilians. When, at the 2009 Davos Summit, Turkey’s then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Israeli President Simon Peres sat on the same panel, Erdoğan criticized Peres severely for his country’s offensive in Gaza, accusing Israel of conducting “state terrorism” and walked out of the panel. But diplomatic relations were still in place between the two countries until the Mavi Marmara flotilla crisis of May 2010. The Mavi Marmara was a humanitarian aid vessel that aimed to break the sea blockade on Gaza. While it held both Turkish and non-Turkish activists, the initiative was organized by a Turkish humanitarian aid organization (İHH, İnsani Yardım Vakfı) and the vessel carried the Turkish flag. Israel did not allow the vessel to reach Gaza’s port and İHH refused to dock in the Ashdod port, consequently, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) raided the flotilla, killing nine people of Turkish origin and one American Turkish citizen. -

Palestine and the Struggle for Global Justice

Studies in Social Justice Volume 4, Issue 2, 199-215, 2010 Between Acceleration and Occupation: Palestine and the Struggle for Global Justice JOHN COLLINS Department of Global Studies, St. Lawrence University ABSTRACT This article explores the contemporary politics of global violence through an examination of the particular challenges and possibilities facing Palestinians who seek to defend their communities against an ongoing settler-colonial project (Zionism) that is approaching a crisis point. As the colonial dynamic in Israel/Palestine returns to its most elemental level—land, trees, homes—it also continues to be a laboratory for new forms of accelerated violence whose global impact is hard to overestimate. In such a context, Palestinians and international solidarity activists find themselves confronting a quintessential 21st-century activist dilemma: how to craft a strategy of what Paul Virilio calls “popular defense” at a time when everyone seems to be implicated in the machinery of global violence? I argue that while this dilemma represents a formidable challenge for Palestinians, it also helps explain why the Palestinian struggle is increasingly able to build bridges with wider struggles for global justice, ecological sustainability, and indigenous rights. Much like the ubiquitous and misleading phrase “Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” the conventional usage of the term “occupation” to describe Israel’s post-1967 control of the West Bank and Gaza serves to deflect attention from the settler-colonial structures that continue to shape the contours of social reality at all levels in Israel/Palestine.1 The dominant discourse of “occupation” is built on an unstated assumption that it is the presence of soldiers, whether that presence is viewed as oppressive or defensive, that makes the territories “occupied.” In fact, contemporary Palestine is the site of not one, but two occupations, both of which are occluded by this assumption. -

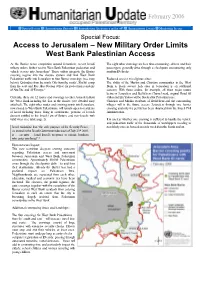

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

Litigating Corporate Complicity in Israeli Violations of International Law in the U.S

97 Corrie et al v. Caterpillar: Litigating Corporate Complicity in Israeli Violations of International Law in the U.S. Courts Grietje Baars* 1 INTRODUCTION1 In 2005 an attempt was made at enforcing international law against an American corporation said to be complicit in war crimes, extrajudicial killing and cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment committed by the Israeli military. The civil suit, brought in a U.S. court, was dismissed without a hearing, in a brief statement mainly citing reasons of political expedience. The claimants in Corrie et al v. Caterpillar2 include relatives of several Palestinians, and American peace activist Rachel Corrie, who were killed or injured in the process of house demolitions carried out using Caterpillar’s D9 and D10 bulldozers. They brought a civil suit in a U.S. court under the Alien Tort Claims Act,3 for breaches of international law, seeking compensatory damages and an order to enjoin Caterpillar’s sale of bulldozers to Israel until its military stops its practice of house demolitions. An appeal is pending and will be decided on in the latter half of 2006. * PhD Candidate, University College London and Coordinator, International Criminal Law at the Institute of Law, Birzeit University. 1 The author thanks Victor Kattan, Jason Beckett, Jörg Kammerhofer, Akbar Rasulov, André de Hoogh, Anne Massagee, Reem Al-Botmeh and Munir Nuseibah for their helpful comments and suggestions, and Maria LaHood of the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York for providing the documentation. Any mistakes are the author’s own. This article is an elaboration of a paper presented at the conference, “The Question of Palestine in International Law” at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, on 23-24 November 2005. -

Israel's Investigation of Alleged Violations of The

Israel’s Investigation of Alleged Violations of the Law of Armed Conflict Israel is well aware of allegations of violations of international law during Operation Protective Edge (hereinafter: the 2014 Gaza Conflict). Israel reviews complaints and other information suggesting IDF misconduct, regardless of the source. Moreover, Israel is committed to investigating fully any credible accusation or reasonable suspicion of a serious violation of the Law of Armed Conflict,1 and in fact its policy of carrying out investigations goes beyond its obligation under international law. In 2010 the Government of Israel created an independent public commission of inquiry headed by retired Israeli Supreme Court Justice Jacob Turkel and observed by international legal experts (the “Turkel Commission”), whose mandate included an assessment of Israel’s mechanisms for examining and investigating complaints and claims regarding alleged violations of the Law of Armed Conflict. The Turkel Commission reviewed Israel’s investigations systems, including the military system of justice — which includes a multi-stage process directed by Israel’s Military Advocate General (the “MAG”), Military Courts, civilian oversight by the Attorney General of Israel, and judicial review by the Supreme Court of Israel — in light of the “general principles” for conducting an effective investigation under international law: independence, impartiality, effectiveness and thoroughness, and promptness.2 Following a careful and comprehensive review, the Turkel Commission concluded in 2013 -

Records Related to Turkish Consul Ali Sait Akin and Any and All Member

' .----N-l_b__fo-r-- - ---.Approved for release by ODNI on 3/17/2016, FOIA Case DF-2013-00182 0 0 3 8 11 redacted portions. UNCLASSIFIED Subject FOIA Request Reviews - 2013-1612 -DOS NC I (,;/UOS/rU To: From: ······Chief of Staff unclassified . - classified; - Date: 12/05/2013 03:26 PM Th s message 1s digitally sig a . Classification: UNCLASSIFIED ====================================================== Please see below for NCTC/DOS' inputs to the FOIA Request under Tasking 2013-1612-DOS. If you -··have any questions, please contact as I will be out of the office on Friday returning on Monday, 9 December. •Thanks, =+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+=+= Chief of Staff -Directorate of Operations Sup classified: unclassified: ---- Forwarded b·········••lon 12/05/2013 03:24 PM---- Regarding_second item on Turkish Consul Ali Sait Akin, NCTOC found the follow two articles •••I •••• from 8 March 2013 and 26 October 2012: Media Highlights Friday, 08 March 2013 56. Benghazi cover-up continues, nearty six months later Una ... Media Highlights Friday, 08 March 2013 56. Benghazi cover -up continues, nearty six months later Unanswered questions linger on 9111 attacks James A. Lyons, Washington Times • 08 March 2013 One of the hopeful outcomes of the Senate confirmation hearings for John Brennan to be director of the Central Intelligence Agency and Chuck Hagel to be the secretary of Defense was to gain some concrete answers to the Benghazi tragedy. So far, though, no additional useful information has been released . Further, the testimony of fonTier Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Martin Dempsey on Feb. 7 before the Senate Armed Services Committee only raised more questions. -

Directions for a Middle East Settlement—Some Underlying

DIRECTIONS FOR A MIDDLE EAST SETTLEMENT- SOME UNDERLYING LEGAL PROBLEMS SHABTAI ROSENNE* I INTRODUCTION A. Legal Framework of Arab-Israeli Relations The invitation to me to participate in this symposium suggested devoting attention primarily to the legal aspects and not to the facts. Yet there is great value in the civil law maxim: Narra mihi facta, narabo tibi jus. Law does not operate in a vacuum or in the abstract, but only in the closest contact with facts; and the merit of legal exposition depends directly upon its relationship with the facts. It is a fact that as part of its approach to the settlement of the current crisis, the Government of Israel is insistent that whatever solution is reached should be em- bodied in a secure legal regime of a contractual character directly binding on all the states concerned. International law in general, and the underlying international legal aspects of the crisis of the Middle East, are no exceptions to this legal approach which integrates law with the facts. But faced with the multitude of facts arrayed by one protagonist or another, sometimes facts going back to the remotest periods of prehistory, the first task of the lawyer is to separate the wheat from the chaff, to place first things first and last things last, and to discipline himself to the most rigorous standards of relevance that contemporary legal science imposes. The authority of the Interna- tional Court itself exists for this approach: the irony with which in I953 that august tribunal brushed off historical arguments, in that instance only going back to the early feudal period, will not be lost on the perceptive reader of international juris- prudence.' Another fundamental question which must be indicated at the outset relates to the very character of the legal framework within which the political issues are to be discussed and placed. -

Shabtai Rosenne and the International Court of Justice*

The Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals 12 (2013) 163–175 brill.com/lape Shabtai Rosenne and the International Court of Justice* Dame Rosalyn Higgins DBE QC Former President of the International Court of Justice It is by now well known in the world of international law that a new Judge at the International Court of Justice finds awaiting him or her on the office bookshelf not only the Pleadings, Judgments and Opinions of the Perma- nent Court of Justice and of the International Court of Justice, but the four volumes of Shabtai Rosenne’s The Law and Practice of the International Court, 1920–2005. Of course, there have over the years been many well-respected and knowledgeable writers on the Court. But the question arises: how could it be, that one who was never (for various reasons unrelated to his ability) a Judge of the International Court, produced thousands of pages, so full of insight and understanding, and precise in their formulation, that they have come to be regarded as somehow determinative of issues that arose in the life of the Court? These volumes were a marvel, yes, but how could they be so, especially as they were written by an author who had not ‘lived within the Court’? The answer is twofold: first, Shabtai Rosenne was a great, great man and scholar. Second, for nearly sixty years he had an ‘inside track’ at the Court. And he had it because he noted, he saw, he compared, and he asked, asked, and asked again – seeking information and explanations from seven Regis- trars. -

The İHH Riddle Why It Doesn’T Make Sense to List the Turkish Humanitarian Group As a Foreign Terrorist Organization

The İHH Riddle Why It Doesn’t Make Sense to List the Turkish Humanitarian Group as a Foreign Terrorist Organization Melis Tusiray, Peter Juul, and Michael Werz July 2010 The Senate’s call to designate the Turkish Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief as a foreign terrorist organization, or FTO, is counterproductive to U.S. efforts to recognize and respond to terrorist threats. Eighty-seven senators have signed a letter calling on the Obama administration to “consider whether the İHH should be put on the list of foreign terrorist organiza- tions.” The İHH is a humanitarian organization run out of Turkey and active in over 100 locations worldwide. It also organized the Gaza-bound flotilla involved in the raid in late May. The letter correctly points out that İHH has questionable links to the Hamas-run Union of Good, but it fails to specify how it wants to des- ignate the İHH as a terrorist organization and could therefore damage our security and relationship with Turkey. The Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, lays out an FTO designation that includes strict sanctions and is usually narrowly applied to violent organizations. The Departments of State, Justice, Treasury, and Homeland Security follow this designation, which is often collectively referred to as the “FTO list.” But the Bush administration’s Executive Order 13224 allows for a broader FTO definition with fewer consequences that is often applied to organizations that provide resources -

The Raid on the Free Gaza Flotilla on 31 May 2010 Opinion on International Law By

EJDM Europäische Vereinigung von Juristinnen und Juristen für Demokratie und Menschenrechte in der Welt e.V. ELDH European Association of Lawyers for Democracy and World Human Rights EJDH Asociacion Europea de los Juristas por la Democracia y los Derechos Humanos en el Mundo EJDH Association Européenne des Juristes pour la Démocratie et les Droits de l’Homme dans le Monde EGDU Associazione Europea delle Giuriste e dei Giuristi per la Democrazia e i Diritti dell’Uomo nel Mondo Professor Bill Bowring, President (London) Professeure Monique CHEMILLIER- GENDREAU, Présidente d’honneur (Paris) Thomas SCHMIDT (Rechtsanwalt) Secretary General (Duesseldorf) The raid on the Free Gaza Flotilla on 31 May 2010 Opinion on international law by Prof. em. Dr. Norman Paech University of Hamburg I. The facts The raid by the Israeli army on the Free Gaza Flotilla in the early morning of 31 May 2010 aroused worldwide indignation. In the raid, nine passengers on the Mavi Marmara, sailing under the Turkish flag, died, and at least forty-five were injured, some of them seriously. While a considerable body of opinion sees this as a serious breach of international law, and even speaks of war crimes, the Israeli army regards itself as fully justified, and following an internal review has admitted only that there were some slips in the planning and execution of the seizure of the ships1. Before the events can be further analysed with regard to international law, it is first necessary to set out the sequence in which they occurred, which is constantly being described differently. Only six of the original eight ships gathered on 30 May in international waters, far south of the island of Cyprus and east of Israel. -

B'tselem and Hamoked Report: One Big Prison

One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 Researched and written by Yehezkel Lein Data coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Ariana Baruch, Reem ‘Odeh, Shlomi Swissa Fieldwork by Musa Abu Hashhash, Iyad Haddad, Zaki Kahil, Karim Jubran, Mazen al-Majdalawi, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi Assistance on legal issues by Yossi Wolfson Translated by Zvi Shulman, Shaul Vardi Edited by Rachel Greenspahn Cover photo: Palestinians wait for relatives at Rafah Crossing (Muhammad Sallem, Reuters) ISSN 0793-520X B’TSELEM - The Israeli Center for Human Rights HaMoked: Center for the Defence of in the Occupied Territories was founded in 1989 by a the Individual, founded by Dr. Lotte group of lawyers, authors, academics, journalists, and Salzberger is an Israeli human rights Knesset members. B’Tselem documents human rights organization founded in 1988 against the abuses in the Occupied Territories and brings them to backdrop of the first intifada. HaMoked is the attention of policymakers and the general public. Its designed to guard the rights of Palestinians, data are based on independent fieldwork and research, residents of the Occupied Territories, official sources, the media, and data from Palestinian whose liberties are violated as a result of and Israeli human rights organizations. Israel's policies. Introduction “The only thing missing in Gaza is a morning Since the beginning of the occupation, line-up,” said Abu Majid, who spent ten Palestinians traveling from the Gaza Strip to years in Israeli prisons, to Israeli journalist Egypt through the Rafah crossing have needed Amira Hass in 1996.1 This sarcastic comment a permit from Israel.