Chapter HI MILITARY ADMINISTRATION of THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

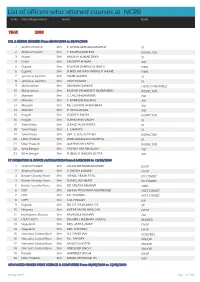

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Please Read: a Personal Appeal from Wikipedia Founder Jimmy Wales

Please read: A personal appeal from Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales Indian Air Force From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Indian Air force Ensign of the Indian Air Force Active 8 October 1932 – present Country India Branch Air Force Size 170,000 active personnel 1300 aircraft [1] Part of Ministry of Defence Indian Armed Forces Headquarters New Delhi, India Motto नभःसपृशं दीपतम् Sanskrit: Nabhaḥ -Sp ṛ śa ṃ Dīptam "Touch the Sky with Glory"[2] Colour Navy blue, Sky blue & White Anniversaries Air Force Day: 8th October[3] Engagements World War II Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 Congo Crisis Operation Vijay Sino-Indian War Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 Bangladesh Liberation War Operation Meghdoot Operation Poomalai Operation Pawan Operation Cactus Kargil War Decorations Indian Military Honour Awards Battle honours Param Vir Chakra Website indianairforce.nic.in Commanders Chief of the Air Air Chief Marshal Pradeep Vasant Staff Naik Vice Chief of the Air Marshal Pranab Kumar Air Staff Barbora Insignia Crest Roundel Fin flash Aircraft flown Attack Jaguar, MiG-27, Harpy Electronic IAI Phalcon warfare Fighter Su-30MKI, Mirage 2000, MiG- 29,MiG-21 Helicopter Dhruv, Chetak, Cheetah, Mi-8, Mi- 17, Mi-26, Mi-25/35 Reconnaissance Searcher II, Heron Trainer HPT-32 Deepak, HJT-16 Kiran, Hawk Mk 132 Transport Il-76, An-32, HS 748, Do 228,Boeing 737, ERJ 135, Il- 78MKI The Indian Air Force (IAF; Devanāgarī: भारतीय वायु सेना, Bhartiya Vāyu Senā) is the air arm of the Indian armed forces. Its primary responsibility is to secure Indian airspace and to conduct aerial warfare during a conflict. -

To All These Members Who Wrote and to the Many More Who May Not Have, I Must Agree That There Is a Certain Truth in All These Char- Ges

To all these members who wrote and to the many more who may not have, I must agree that there is a certain truth in all these char- ges. I will accept the gentleman’s offer of the new hat, doff it to him, and acknowledge the truth of all he said. For an editor is all of those things. It comes with the job. tie is a censor, a dictator, an autocrat, a sole voice, and a correcter and a selector, lle accepts and he turns down. He publishes or else he refuses to. But dictator- ships, the same as any other type of organized human activity, have also to have at their basis some fundamental set of goals. The Editor Speaks as the Fiihrer spoke. But in speaking he has also to remain consistant with these underlying purposes. Yet statistically I have been a mild dictator. Nearly every arti- cle and picture and indeed every advertisement eventually saw itself in print. This issue not only marks bringing the journal back up to date, it also marks the publication of the last of the old material sent in times past to the former editor. So these i~sues stand as m~ record. There is also no more material. It is now all in. That is all she wrote! We are living through an age when Americans are undergoing an emotion conflict between older concepts of individualism and democracy and the restraints and required obligations of life lived in a crowded, competitive society. Some people therefore use the officers of hobby clubs and social organizations as whipping boys for their own frustra- tions. -

Indian National Army

HIS5B09 HISTORY OF MODERN INDIA MODULE-4 TOPIC- INDIAN NATIONAL ARMY Prepared by Dr.Arun Thomas.M Assistant Professor Dept of History Little Flower College Guruvayoor Indian National Army • Indian National Army • The idea of the Indian National Army (INA) was first conceived in Malaya by Mohan Singh, an Indian officer of the British Indian Army, when he decided not to join the retreating British Army and instead turned to the Japanese for help. • The Japanese handed over the Indian prisoners of war (POWs) to Mohan Singh who tried to recruit them into an Indian National Army. • In1942, After the fall of Singapore, Mohan Singh further got 45,000 POWs into his sphere of influence. • 2 July 1943, Subhash Chandra Bose reached Singapore and gave the rousing war cry of ‘Dilli Chalo’ • Was made the President of Indian Independence League and soon became the supreme commander of the Indian National Army • Here he gave the slogan of Jai Hind • INA’s three Brigades were the Subhas Brigade, Gandhi Brigade and Nehru Brigade. • The women’s wing of the army was named after Rani Laxmibai. • INA marched towards Imphal after registering its victory over Kohima but after Japan’s surrender in 1945, INA failed in its efforts. • Under such circumstances, Subhash went to Taiwan & further on his way to Tokyo he died on 18 August 1945 in a plane crash. • Trial of the soldiers of INA was held at Red Fort in Delhi. • Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, Kailash Nath Katju, Asaf Ali and Tej Bahadur Sapru fought the case on behalf of the soldiers. -

Recruitment and Motivation of the Indian National Army

The British Empire at War Research Group Research Papers No. 6 (2014) ‘Waging War against the King’: Recruitment and Motivation of the Indian National Army, 1942-1945 Kevin Noles 1 The British Empire at War Research Papers series publishes original research online, including seminar and conference presentations, theses, and synoptical essays. British Empire at War Research Group Defence Studies Department, King’s College London Email: [email protected] Website: http://britishempireatwar.org 2 Background and abstract The Indian National Army has been neglected in accounts of the Second World War in South-east Asia. It grew out of the defeat of British Empire forces in Malaya and Singapore in 1942, with captured Indian officers and men of the British Indian army volunteering to fight alongside the Japanese in order to further the cause of Indian nationalism. It was formed with an initial strength of sixteen thousand in late 1942 but before it could be deployed on operations differences emerged between its military leadership and the Japanese over how it would be employed. Although as a result it was partially disbanded the arrival in mid-1943 of credible political leadership, in the form of Indian revolutionary Subhas Chandra Bose, led to its reinvigoration. It was expanded to a size of forty thousand, in part through the incorporation of civilian volunteers, and saw action in India and Burma in 1944 and 1945 although its combat performance was variable. Its character is better thought of as an armed revolutionary force rather than as a conventional army. Its methods of recruitment varied over time with there being evidence of coercion during 1942 although others joined willingly. -

Catalogue of the Papers of Captain Lakshmi Sahgal

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Captain Lakshmi Sahgal Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Captain Lakshmi Sahgal (1914-2012) Freedom fighter, social activist and the first woman commander of Indian National Army, Lakshmi Sahgal nee Swaminadhan was born on 24 October 1914 in Madras (now Chennai) to S. Swaminadhan, a criminal lawyer at Madras High Court, and Ammu Swaminadhan, a social worker and freedom fighter. Inspired by the progressive views of her mother, Lakshmi broke social convention and dogmas from a very early stage speaking out against the caste practices in Kerala. She joined the Queen Mary’s College, Madras in 1932. She was married at a young age to P.K.N Rao, a pilot. However, the marriage was not a success and she returned to her hometown to resume her studies. She completed her MBBS in 1938 from Madras Medical College. She also obtained a diploma in gynaecology and obstetrics from the same college in 1940 and joined the Government Kasturba Gandhi Hospital, Madras. Thereafter, she moved to Singapore and established a clinic for the poor and migrant workers from India. She also got closely associated with the India Independence League, founded in 1941 by Rash Behari Bose. In 1942, during the Japanese occupation of Singapore Dr. Lakshmi provided medical aid to the prisoners of war. Subhas Chandra Bose visited Singapore in July 1943 and took over the leadership of the League along with the Indian National Army. Dr. Lakshmi was inspired and fascinated by the charismatic leadership of Bose and expressed her desire to work with him. -

Indian National Movement-Indian National Army and Evolution of Princely States

9/27/2021 Indian National Movement Indian National Army and Evolution of Princely States- Examrace Examrace Indian National Movement-Indian National Army and Evolution of Princely States Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for NTSE/Stage-II-National-Level : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of NTSE/Stage- II-National-Level. Indian National Army The Foundation of Indian National Army In 1939 - 40, Subhash Chandra Bose dissatisfied with the political ideology of the Indian National Congress. On 16 - 17 January 1941, Netaji slipped out of his Elgin Road home in disguise and with an assumed name of Maulvi Ziauddin he reached Delhi and boarded the Frontier Mail for Peshawar. He reached Japan where he was received by Rash Behari Bose. Rash Behari Bose, one of the oldest Indian revolutionaries escaped from India after dropping a bomb on Lord Hardingein 1911. On 15th July 1942 the Indian National Army was formed as an organized body of troops. Capt. Mohan Singh became the General Officer Commanding of the Indian National Army. But, by December 1942, serious differences emerged between the INA officers led by Mohan Singh and the Japanese over the role that the INA was to play. Mohan Singh and Niranjan Singh Gill were arrested Netaji arrived in Singapore on 2 July 1943 and on the 25 August, he assumed Supreme Command of the USA. On 21 October 1943, Netaji formed the Provisional Government of Azad Hind. This Government was recognized by all the axis powers. Advance Headquarters of INA and the Provisional Government of Azad Hind headed by Netaji also moved to Rangoon. -

S. No. Name (Mr./Ms) Father's/Husband's Name Correspondence Address Date of Birth 1 Ms. Vijayta Raghav Mr. Manmohan Raghav C/O S

PERSONAL ASSISTANT EXAMINATION-2013 List of Eligible Candidates Date of Examination will be intimated later on. S. No. Name (Mr./Ms) Father's/Husband's Name Correspondence Address Date of Birth C/o suresh Kumar, H.NO. 61, 1 Ms. Vijayta Raghav Mr. Manmohan Raghav Village- Motibagh, Nr. 8.09.1985 Nanakpura, N.D. 21. DB-75 A, DDA Flats, Hari 2 Ms. Shalini Sharma Mr. Gaurav Rana 5.11.1984 Nagar, New Delhi -64 D-8/184, East Gokal Pur, 3 Mr. Deepak Kumar Mr. Atal Singh 2.04.1985 Shahdara North East Delhi-94. WZ-303, Sant Garh, St. No. 18, 4 Ms. Surinder Kaur Mr. Daljeet Singh Ground Floor, M.B.S. Nagar, 15.06.1987 Tilak Nagar, New Delhi -18. E-196, Sector-23, Sanjay Nagar, 5 Ms. Jyoti Mr. Rajesh Kumar 18.02.1988 Ghaziabad, UP - 201002. 57-P, DIZ Area, Gole Market 6 Ms. Richa Bajaj Mr. Kamal Bajaj (Raja Bazar), Sec.-4, New Delhi- 5.05.1982 01. H.No. 50, Krishan Kunj colony, 7 Ms. Neetu Kansal Mr. Manish Kansal 18.04.1987 Laxmi Nagar, Delhi - 92. CBI Academy, Hapur Road, 8 Ms. Bharati Sharma Mr. Kamal Prakash Sharma Kamla Nehru Nagar, 22.02.1990 Ghaziabad, U.P.- 201002. H.No. 6612, Radhey Puri, Ext. 9 Ms. Rekha Mahour Mr. Dinesh Kumar 2.07.1989 No. 2, Krishna Nagar, Delhi -51. A/561, Madi Pur Colony, New 10 Ms. Madhu Bala Lt. Mr. Madan Lal 1.11.1986 Delhi - 63. D-106, Gali No. 5, Laxmi Nagar, 11 Ms. Premlata Mr. Dayaram Sharma 28.7.1990 New Delhi-92. -

Mohan Singh (General)

Mohan Singh (general) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Mohan Singh Singh (in turban) being greeted by the Japanese Major Fujiwara Iwaichi, April 1942 3 January 1909 Born Ugoke, Sialkot, Punjab, British India (present- day Punjab, Pakistan) 1989 (aged 79–80) Died Jugiana, Ludhiana, Punjab, India Nationality Indian Occupation Soldier Founding General of the First Indian National Known for Army Movement Indian Independence movement Shahmukhi); 1909 – 1989) was an) موہن سنگھ ;(Mohan Singh (Punjabi: ਮੋਹਨ ਸ ︂ਘ (Gurmukhi Indian military officer and member of the Indian Independence Movement best known for his role in organising and leading the First Indian National Army in South East Asia during World War II. Following Indian independence, Mohan Singh later served in public life as a Member of Parliament in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House) of the Indian Parliament. Contents [hide] • 1 Early life • 2 Military career • 3 Second World War o 3.1 Action in Malaya o 3.2 Indian National Army o 3.3 Disagreements with Japan • 4 Post 1947 • 5 Death • 6 Notes • 7 Bibliography • 8 External links Early life[edit] He was born the only son of Tara Singh and Hukam Kaur, a couple of Ugoke village, near Sialkot (now in Pakistan). His father died two months before his birth and his mother shifted to her parents home in Badiana in the same district, where Mohan Singh was born and brought up. Military career[edit] As he passed high school, he enlisted the 14th Punjab Regiment of the British Indian Army in 1927. After the completion of his recruit training at Hrozpur, Mohan Singh was posted to the 2nd Battalion of the Regiment, then serving in the North-West Frontier Province. -

Rai Bahadur Mohan Singh Oberoi: Father of the Indian Hotel Industry by Prakash K

Rai Bahadur Mohan Singh Oberoi: Father of the Indian Hotel Industry By Prakash K. Chathoth, Ph.D. and Kaye K.S. Chon, Ph.D. ntroduction (“The Padma Bhushan is an Indian civilian decoration in Pakistan) for higher education, I A good majority of the hotel established on January 2, 1954 by the President of In- which he later abandoned to pursue graduates from institutions in hos- dia. It stands third in the hierarchy of civilian awards, a career. As a student in Rawal- pitality education in India would after the Bharat Ratna and the Padma Vibhushan, but pindi, Mohan Singh was mesmerized rate the Oberoi Group as their comes before the Padma Sri. It is awarded to recognize by the beauty of the best hotel in most preferred hotel company for distinguished service of a high order to the nation, in town in the early twentieth century launching their career. Such is the any field.” This definition is extracted from http:// - Hotel Flashmans- that he later regard aspiring hotel professionals en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Padma_Bhushan, verbatim.) acquired. have for this firm that it has re- M. S. Oberoi’s contribution as an hotelier is not His quest to start earning drove mained one of the most preferred only at the national level in India, but also extends to him to Lahore (now in Pakistan), hotel companies in India over the international level, especially within Asia. He has where he joined his uncle’s shoe several decades. It takes leader- contributed to the growth of the hospitality and tour- business. Although he was success- ship and vision on the part of the ism industry in various lands, encompassing countries ful in establishing himself in his firm’s management to achieve this such as Indonesia, Mauritius, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and uncle’s business, the factory closed status, and without doubt, the Australia. -

At the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. BETWEEN SELF AND SOLDIER: INDIAN SIPAHIS AND THEIR TESTIMONY DURING THE TWO WORLD WARS By Gajendra Singh Thesis submitted to the School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History 2009 ! ! "! ! Abstract This project started as an attempt to understand rank-and-file resistance within the colonial Indian army. My reasons for doing so were quite simple. Colonial Indian soldiers were situated in the divide between the colonizers and the colonized. As a result, they rarely entered colonialist narratives written by and of the British officer or nationalist accounts of the colonial military. The writers of contemporary post-colonial histories have been content to maintain this lacuna, partly because colonial soldiers are seen as not sufficiently ‘subaltern’ to be the subjects of their studies. -

Seti^ Parlayed on Ttrtns of Equality with Nine Powers of the World Tnctu4iing

Seti^ parlayed on ttrtns of equality with nine Powers of the world tnctu4iing Japan, Germany uud Italy after establishing the Provisional GovernMeni of Free India OK 21st October, 194S, for the first time in Indian Historv since British Rule began. UNTO HIM A, NXaTNESS ^., . THE STORY HBiMt ^.U-9C NETAJI SUBHAS CH>iwUKA BUSt IN EAST ASIA S. A. AYER PROCESSED \\^> PRESENTED BY J. {Ughotham Reddy "BriiMlavan" 17J. Fateh Maidan North Rd; IH>derabad-30 0 004 THACKER & C6., LTD. BOMBAY .•^i..-.>^ •j.TJ^l.. LUJ. •' —' • ' ''* TO ALL KNO^'N AND VNKNO^'K WARRJOFS OF INDIA'S INDEPENDENCE CONTENTS PREFACE Page WHY THIS BOOK? ix NETAJI AND I11YSEX.F . xxii ROAD TO DELHI . xxviii PART ONE CHAP. I A DRE^V^I BECO3IES A REALITV 1 CHAP. II EPIC IN EAST ASL\ 5 CHAP. in HISTORIC RETREAT 1-i CHAP. JV THE FORCED 3L\Rcn 25 CHAP. V ENCIKCLIXG GLOOM 48 CHAP. VI THE LAST FLIGHT 6e> CHAP. VII THE SAD, SAD NEWS 7-t CHAP. vni. Ix VANQUISHED JAPAN 93 CHAP. IX. FEARS AND TEARS 107 CHAP. X. THE CALL FROM THE RED FORT 118 CHAP. XI. UNTO HIM A WITN-ESS 132 PART TWO CHAP. I. DAWN OF FREEDOM—^BEHIND THE SCENES .... 153 CHAP. II LIFE WITH NETAJI—THE REAL ISLLS 1G7 CHAP. III CRUCL\L DAYS—A LEADER'S iviETTLE IS-i CHAP. VI INDIA'S ^VIOIY OF LIBERATION . 210 CHAP. V STATESILVN AND DIPLOJIAT 215 PART THREE CHAP. I NETAJI THE SAVIOUR . • 23.3 CHAP. II FLASHES OF THE FIGHTER 240 CHAP. in DEMOCRAT OR DICTATOR ? 250 CHAP.