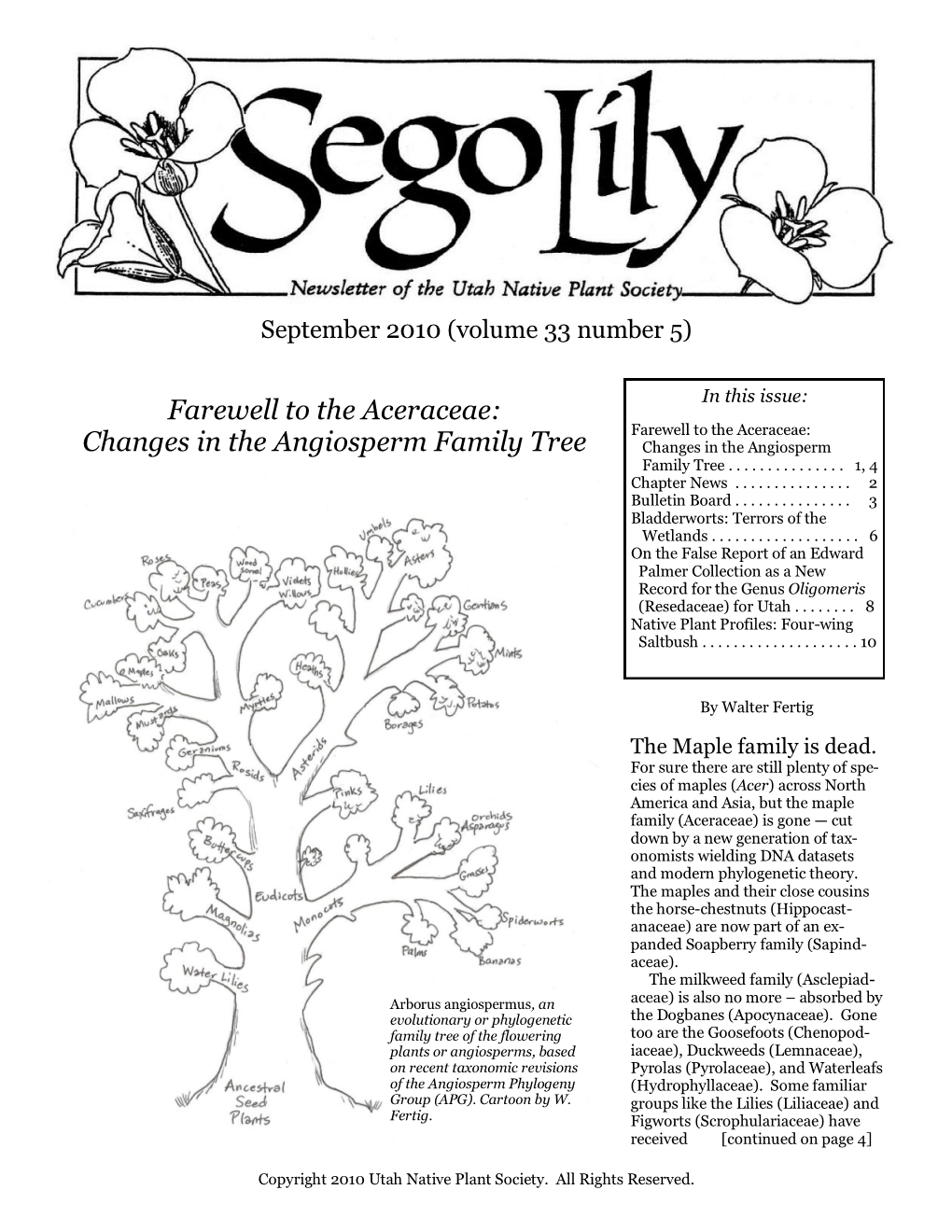

Farewell to the Aceraceae: Changes in the Angiosperm Family Tree Changes in the Angiosperm Family Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liliaceae S.L. (Lily Family)

Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) Photo: Ben Legler Photo: Hannah Marx Photo: Hannah Marx Lilium columbianum Xerophyllum tenax Trillium ovatum Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) Photo: Yaowu Yuan Fritillaria lanceolata Ref.1 Textbook DVD KRR&DLN Erythronium americanum Allium vineale Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) Herbs; Ref.2 Stems often modified as underground rhizomes, corms, or bulbs; Flowers actinomorphic; 3 sepals and 3 petals or 6 tepals, 6 stamens, 3 carpels, ovary superior (or inferior). Tulipa gesneriana Liliaceae s.l. (Lily family) “Liliaceae” s.l. (sensu lato: “in the broad sense”) - Lily family; 288 genera/4950 species, including Lilium, Allium, Trillium, Tulipa; This family is treated in a very broad sense in this class, as in the Flora of the Pacific Northwest. The “Liliaceae” s.l. taught in this class is not monophyletic. It is apparent now that the family should be treated in a narrower sense and some of the members should form their own families. Judd et al. recognize 15+ families: Agavaceae, Alliaceae, Amarylidaceae, Asparagaceae, Asphodelaceae, Colchicaceae, Dracaenaceae (Nolinaceae), Hyacinthaceae, Liliaceae, Melanthiaceae, Ruscaceae, Smilacaceae, Themidaceae, Trilliaceae, Uvulariaceae and more!!! (see web reading “Consider the Lilies”) Iridaceae (Iris family) Photo: Hannah Marx Photo: Hannah Marx Iris pseudacorus Iridaceae (Iris family) Photo: Yaowu Yuan Photo: Yaowu Yuan Sisyrinchium douglasii Sisyrinchium sp. Iridaceae (Iris family) Iridaceae - 78 genera/1750 species, Including Iris, Gladiolus, Sisyrinchium. Herbs, aquatic or terrestrial; Underground stems as rhizomes, bulbs, or corms; Leaves alternate, 2-ranked and equitant Ref.3 (oriented edgewise to the stem; Gladiolus italicus Flowers actinomorphic or zygomorphic; 3 sepals and 3 petals or 6 tepals; Stamens 3; Ovary of 3 fused carpels, inferior. -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Plant Classification, Evolution and Reproduction

Plant Classification, Evolution, and Reproduction Plant classification, evolution and reproduction! Traditional plant classification! ! A phylogenetic perspective on classification! ! Milestones of land plant evolution! ! Overview of land plant diversity! ! Life cycle of land plants! Classification “the ordering of diversity into a meaningful hierarchical pattern” (i.e., grouping)! The Taxonomic Hierarchy! Classification of Ayahuasca, Banisteriopsis caapi! Kingdom !Plantae! Phylum !Magnoliophyta Class ! !Magnoliopsida! Order !Malpighiales! Family !Malpighiaceae Genus ! !Banisteriopsis! Species !caapi! Ranks above genus have standard endings.! Higher categories are more inclusive.! Botanical nomenclature Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778)! Species Plantarum! published 1753! 7,300 species! Botanical nomenclature Polynomials versus binomials! Know the organism “The Molesting Salvinia” Salvinia auriculata (S. molesta)! hp://dnr.state.il.us/stewardship/cd/biocontrol/2floangfern.html " Taxonomy vs. classification! Assigning a name! A system ! ! ! Placement in a category! Often predictive ! because it is based on Replicable, reliable relationships! results! ! Relationships centered on genealogy ! ! ! ! Edward Hitchcock, Elementary Geology, 1940! Classification Phylogeny: Reflect hypothesized evolution. relationships! Charles Darwin, Origin of Species, 1859! Ernst Haeckel, Generelle Morphologie der Organismen, 1866! Branching tree-like diagrams representing relationships! Magnolia 1me 2 Zi m merman (1930) Lineage branching (cladogenesis or speciation) Modified -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes Among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Kristina Marie Gill Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Glassow, Chair Professor Michael A. Jochim Professor Amber M. VanDerwarker Professor Lynn H. Gamble September 2015 The dissertation of Kristina Marie Gill is approved. __________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim __________________________________________ Amber M. VanDerwarker __________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble __________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow, Committee Chair July 2015 Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California Copyright © 2015 By Kristina Marie Gill iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Family, Mike Glassow, and the Chumash People. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have provided guidance, encouragement, and support in my career as an archaeologist, and especially through my undergraduate and graduate studies. For those of whom I am unable to personally thank here, know that I deeply appreciate your support. First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Michael Glassow for his patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement during all aspects of this daunting project. I am also truly grateful to have had the opportunity to know, learn from, and work with my other committee members, Mike Jochim, Amber VanDerwarker, and Lynn Gamble. I cherish my various field experiences with them all on the Channel Islands and especially in southern Germany with Mike Jochim, whose worldly perspective I value deeply. I also thank Terry Jones, who provided me many undergraduate opportunities in California archaeology and encouraged me to attend a field school on San Clemente Island with Mark Raab and Andy Yatsko, an experience that left me captivated with the islands and their history. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Page 1 of 9 BIOL 325 – Plant Systematics Name

BIOL 325 – Plant Systematics Name: ___________________________ Sample Topics & Questions for Exam 1 This document and questions are the copyright of CRHardy, 2016 onwards. Topic 01 – Introduction, Sample Topics & Questions: 1. What major topics to Rhoads and Block (2007) discuss in the introduction to their book? 2. What are the reasons that Prather et al. (2004) list for continued herbarium collecting even in places like North America the flora is thought to be well known? 3. What method(s) does Dirig (2005) discuss for mounting pressed specimens to herbarium sheets? 4. What methods does Dirig (2005) discuss for collecting plant specimens for later pressing? 5. What do the graphs used by Prather et al. (2004) show about herbarium plant collecting in the US? 6. How does one define plant systematics? Name at least one synonym for plant systematics? 7. What are practitioners of plant systematics called and what are some of their important products? 8. Be able to explain how each of these products are important to people and other scientists outside the field of systematics. 9. What is a phylogeny? 10. What is a herbarium? 11. Name the important components of a herbarium specimen. 12. What are herbarium specimens used for? 13. Although taxonomy and systematics are often treated as synonyms by many, they are not actually the same thing. Which of the two is a broader term and how so? 14. The far majority of plant species are described from studies in ... a. botanical gardens b. herbaria c. the field d. plant nurseries e. zoological museums Page 1 of 9 15. -

TAXON:Trema Orientalis (L.) Blume SCORE:10.0 RATING

TAXON: Trema orientalis (L.) Blume SCORE: 10.0 RATING: High Risk Taxon: Trema orientalis (L.) Blume Family: Cannabaceae Common Name(s): charcoal tree Synonym(s): Celtis guineensis Schumach. gunpowder tree Celtis orientalis L. peach cedar Trema guineensis (Schumach.) Ficalho poison peach Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 4 Mar 2020 WRA Score: 10.0 Designation: H(Hawai'i) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tropical, Pioneer Tree, Weedy, Bird-Dispersed, Coppices Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed 401 -

Celtis Occidentalis

Celtis occidentalis - American or Common Hackberry (Ulmaceae) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Celtis occidentalis is a tough tree for urban or rural -lateral stems often die back a few inches to give a sites, growing rapidly to provide shade, windbreak, ragged appearance to the ends of branches and/or erosion control under stressful conditions. Trunk -light gray to gray-green FEATURES -very corky to warty ornamental bark, slowly Form becoming platy with age -large deciduous tree -often to 3' or more in diameter on old trees, with -maturing at 70' tall x significant basal flair 50' wide -wood is much stronger than Silver Maple (another -upright oval growth quick shade tree) habit in youth, quickly losing its central USAGE leader and becoming Function rounded to irregular in -shade tree (for highly stressed, poor soil, or wet soil habit with age sites where rapid growth is needed), deciduous -rapid growth rate windbreak, pioneer invader tree Culture Texture -full sun -medium texture overall in foliage and when bare -prefers moist soils but (fine-textured twigs, but bold and irregular branching is adaptable to many pattern) adverse conditions, -average density in foliage but thick when bare including wet or dry Assets sites and poor soils -urban tolerant (dry sites, soil compaction, pollution, -propagated primarily wind, heat, acid or alkaline soil tolerant), ornamental by seed but also by rooted stem cuttings or grafted bark, rapid growth, adaptable to wet -

Mesa Glow Bigtooth Maple

HORTSCIENCE 53(5):734–736. 2018. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI12881-18 plant water relations, leaf relative water content (RWC), specific leaf weight, total Ò leaf area, specific stem length, leaf thickness, ‘JFS-NuMex 3’: Mesa Glow plant height, xylem diameter, leaf, stem, and root dry weight (DW), relative growth rate Bigtooth Maple (RGR), and net assimilation rate (NAR) in 1 plants exposed to multiple cycles of drought Rolston St. Hilaire compared with well-irrigated controls (Bsoul Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State et al., 2006). A cycle of drought consisted of University, P.O. Box 30003, Las Cruces, NM 88003 irrigating plants only after pot gravimetric moisture loss because of evapotranspiration Additional index words. aceraceae, Acer grandidentatum, environmental stress, fall color, reached 56% to 57%. woody ornamentals Initial screening results revealed that se- lected provenances in Texas, New Mexico, and Utah might contain drought-tolerant Bigtooth maple (Acer grandidentatum more upright form, and redder fall colors than ecotypes (Bsoul et al., 2006). This prompted Nutt.) is a woody deciduous tree that is previous bigtooth maple selections. a second round of drought tolerance testing of indigenous only to North America (St. plants from those selected provenances in Hilaire, 2002). The plant has a contiguous Texas, New Mexico, and Utah in an outdoor ° Origin geographic range that covers 18 of latitude field setting from 23 Aug. to 11 Nov. 2003 and includes regions in Utah, Idaho, Wyom- Between 18 Aug. and 3 Nov. 2001, (Bsoul et al., 2007). On 30 Mar. 2003, plants ing, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas (Bsoul mature samaras (seeds) of bigtooth maples were potted into 30-L pots using the same 1 et al., 2006). -

GREAT PLAINS REGION - NWPL 2016 FINAL RATINGS User Notes: 1) Plant Species Not Listed Are Considered UPL for Wetland Delineation Purposes

GREAT PLAINS REGION - NWPL 2016 FINAL RATINGS User Notes: 1) Plant species not listed are considered UPL for wetland delineation purposes. 2) A few UPL species are listed because they are rated FACU or wetter in at least one Corps region.