On the Fault Line European Donor Motives for Aid Allocation to Post-Genocide Rwanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Monde.Fr : Attentat De Kigali En 1994 : Jean-Louis Bruguière Accuse Paul Kagamé

Le Monde.fr : Attentat de Kigali en 1994 : Jean-Louis Bruguière accuse Paul Kagamé Recherchez depuis Identifiez-vous Mot de passe Afrique sur Le Monde.fr sur le web avec » Recevez les newsletters » Faites du Monde.fr votre gratuites page d'accueil mémorisez | oublié? Jeudi 23 novembre 2006 Compte rendu Attentat de Kigali en 1994 : Jean-Louis Bruguière accuse Paul Kagamé LE MONDE | 21.11.06 | 11h11 En savoir plus avant les autres, Le Monde.fr vous fait gagner du temps. Abonnez-vous au Monde.fr : 6 par mois + 30 jours offerts 'escalade politico-judiciaire entre la France et le Rwanda au sujet du génocide de 1994 est sur le point de connaître un épisode-clé. Neuf mandats d'arrêt internationaux doivent être émis, mercredi 22 novembre, par le juge français Jean-Louis Bruguière contre des proches du président rwandais Paul Kagamé. Chargé de l'enquête sur l'attentat contre l'avion du président Juvénal Habyarimana, le 6 avril 1994 – AFP/BERTRAND LANGLOIS Le juge français Jean-Louis Bruguière lors d'une conférence de qui a entraîné le déclenchement du génocide presse à Londres, le 14 novembre 2006. durant lequel près de 800 000 Tutsis ont été tués –, le juge antiterroriste a transmis au parquet une ordonnance de soit-communiqué cinglante contre Chat M. Kagamé, dont Le Monde a eu connaissance. Le Rwanda, dix ans plus tard Stephen Smith analyse le traumatisme et les responsabilités du génocide rwandais. Le juge y affirme que, "pour Paul Kagamé, l'élimination physique du président Habyarimana s'était imposée à partir d'octobre Editorial du "Monde" Un procès salutaire 1993 comme l'unique moyen de parvenir à ses Chronologie Le génocide au Rwanda et ses suites Bilan France-Rwanda : l'ombre du génocide continue à fins politiques", c'est-à-dire "une victoire totale, et peser ce au prix du massacre des Tutsis dits 'de l'intérieur'". -

Gender Relations in Post-Genocide Rwanda

Women’s Status and Gender Relations in Post-Genocide Rwanda This page was generated automatically upon download from the Globethics.net Library. More information on Globethics.net see https://www.globethics.net. Data and content policy of Globethics.net Library repository see https:// repository.globethics.net/pages/policy Item Type Book Authors Mukabera, Josephine Publisher Globethics.net Rights Creative Commons Copyright (CC 2.5) Download date 01/10/2021 01:21:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12424/165632 Ethics Theses 24 Women’s Status and Gender Relations in Post-Genocide Rwanda Focus on the Local and Everyday Life Level Josephine Mukabera Gender Stereotypes | Leadership | Inequality | Wome Religion | Activism | Violence | Family | Pa Identity | Social Institutions | Gender Relations Equality | Rwanda | Women’s Rights Politics | Genocide | Poverty | Democracy | Ge Africa | Gender | Governance | Women’s Status and Gender Relations in Post-Genocide Rwanda Focusing on the Local and Everyday Life Level Women’s Status and Gender Relations in Post-Genocide Rwanda Focusing on the Local and Everyday Life Level Josephine Mukabera Globethics.net Theses No. 24 Globethics.net Theses Director: Prof. Dr. Obiora Ike, Executive Director of Globethics.net in Geneva and Professor of Ethics at the Godfrey Okoye University Enugu/Nigeria. Series Editor: Ignace Haaz, Globethics.net Publications Manager, Ph.D. Globethics.net Series 24 Josephine Mukabera, Women’s Status and Gender Relations in Post-Genocide Rwanda, Focusing on the Local and Everyday Life Level Geneva: Globethics.net, 2017 ISBN 978-2-88931-193-4 (online version) ISBN 978-2-88931-194-1 (print version) © 2017 Globethics.net Assistant Editor: Samuel Davies Globethics.net International Secretariat 150 route de Ferney 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Website: www.globethics.net/publications Email: [email protected] All web links in this text have been verified as of June 2017. -

Senior Rwandan Official Arrested

Senior Rwandan official arrested German police have arrested a senior Rwandan official in connection with the killing of a previous president whose death triggered the 1994 genocide. Rose Kabuye - the chief of protocol for current Rwandan President Paul Kagame - was detained on arrival at Frankfurt on a warrant issued by a French judge. She is one of nine senior Rwandan officials wanted over the shooting down of Juvenal Habyarimana's plane. All are members of the party which ousted the genocidal regime. Correspondents say Ms Kabuye, a former guerrilla fighter with the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), now Rwanda's ruling party, has heroic status in Rwanda. She has since served as an MP and mayor of the capital Kigali, and is one of President Kagame's closest aides. Transfer to France A German diplomat told AFP news agency that Ms Kabuye had been in Germany on private business and that Germany was "bound to arrest her" by a French-issued European arrest warrant. Ms Kabuye has visited the country before but under German law could not be arrested as she was part of an official delegation. "Rwanda has been made aware on several recent occasions that if Ms Kabuye returned to Germany she would be arrested," said the diplomat. Ms Kabuye's lawyer said she would be transferred to France "as quickly as possible". "She is ready to speak to the judges, especially since, to our knowledge, there isn't much in the dossier," said Leon-Lef Forster, referring to the evidence against his client. AFP quoted Rwandan Information Minister Louise Mushikiwabo as saying that Ms Kabuye's arrest was a "misuse of international jurisdiction". -

From Urban Catastrophe to 'Model' City? Politics, Security and Development in Post- Conflict Kigali Article (Accepted Version) (Refereed)

Tom Goodfellow and Alyson Smith From urban catastrophe to 'model' city? Politics, security and development in post- conflict Kigali Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Goodfellow, Tom and Smith, Alyson (2013) From urban catastrophe to 'model' city? Politics, security and development in post-conflict Kigali. Urban studies, 50 (15). ISSN 0042-0980 © 2013 Sage This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/49094/ Available in LSE Research Online: March 2013 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. From urban catastrophe to ‘model’ city? Politics, security and development in post-conflict Kigali Tom Goodfellow and Alyson Smith Forthcoming 2013 in Urban Studies Vol. 50(15) (Special Issue on ‘Cities and Conflict in Fragile States’) Abstract In the years immediately after the 1994 genocide, Kigali was a site of continuing crisis amid extraordinary levels of urban population growth, as refugees returned to Rwanda in their millions. -

The Rwandan Genocide: a Study for Policymakers Engaged in Foreign Policy, Diplomacy, and International Development

Pepperdine Policy Review Volume 13 Article 5 5-7-2021 The Rwandan Genocide: A study for policymakers engaged in foreign policy, diplomacy, and international development Emily A. Milnes Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/ppr Recommended Citation Milnes, Emily A. (2021) "The Rwandan Genocide: A study for policymakers engaged in foreign policy, diplomacy, and international development," Pepperdine Policy Review: Vol. 13 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/ppr/vol13/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Policy at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Policy Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. “‘These events grew from a policy aimed at the systematic destruction of a people… We are reminded of the capacity of people everywhere—not just in Rwanda, and certainly not just in Africa—but the capacity for people everywhere to slip into pure evil. We cannot abolish that capacity, but we must never accept it.’” —President Bill Clinton, Kigali, Rwanda (1998) I. Introduction Over a period of 100 days between April and mid-July of 1994, the Rwandan genocide claimed the lives of approximately 800,000 Rwandans and caused the displacement of an estimated two million refugees into surrounding nations (UNHCR). The eruption of fear, brutality, and violence as Rwandans massacred Rwandans stemmed from decades of civil war fueled by intractable existential, political, and socioeconomic conflicts between Tutsis and Hutus. -

TRIBUNAL DE GRANDE INSTANCE DE PARIS CHAMBERS De Jean-Louis BRUGUIERE First Vice-President Parquet

TRIBUNAL DE GRANDE INSTANCE DE PARIS CHAMBERS de Jean-Louis BRUGUIERE First Vice-President Parquet: 97.295.2303-0 Cabinet: 1341 ISSUANCE OF INTERNATIONAL ARREST WARRANTS ***************************** ORDONNANCE DE SOIT-COMMUNIQUE [Order to Execute] ***************************** Translated from French to English by CM/P. Corrected and layout by Agaculama. This is a free and non official translation, that has been performed in order to correctly inform the English speakers about the « Rwandese genocide ». Any reference to this version, given in an official frame, will be done under the responsibility of the user who will ever explicitely give the reference to the official text, issued by Judge Jean-Louis Bruguière at the Tribunal de Première Instance de Paris. The anonymous authors of this translation can not be pursued for the imperfections that occurred during the benevolent translation. ***************************** We, Jean-Louis Bruguière, Premier Vice-Président of the Tribunal de Grande Instance de Paris, In view of articles 131 and 145 of the Penal Code, (1) Considering that on 6 April 1994 at 8:25 pm, the Falcon 50 of the President of the Republic of Rwanda, registration number "9XR-NN", on its return from a summit meeting in DAR-ES-SALAAM (Tanzania) as it was on approach to Kanombe International Airport in KIGALI, was shot down by two Surface-to-Air Missiles; and (2) That all passengers: - Juvénal HABYARIMANA, Chief of State of Rwanda, - Cyprien NTARYAMIRA, Chief of State of Burundi, - Déogratias NSABIMANA, Chief of Staff of Rwandan -

The Commodification of Genocide: Part II

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 5, No. 5; May 2015 The Commodification of Genocide: Part II. A NeoGramscian Model for Rwanda William R. Woodward Professor Department of Psychology University of New Hampshire Durham, N.H. 03824 USA Jean-Marie VianneyHigiro Professor Department of Communication Western New England University 1215 Wilbraham Rd. Springfield, MA 01119 Abstract In our previous paper, we did a qualitative content analysis of news reports disseminated by international media about events occurring in Rwanda. We grouped these reports into three themes: human rights, security, and foreign relations. Here we add our analysis of four more themes: Hutu menace in the Great Lakes, memorializing the victims, economic situation, and democracy. We argued that news coverage has been de-capitated by the ruling elite and that the western capitalist states have supported this co-optation. To gain access, Western journalists have had to cooperate with the state rather than with critical Rwandan journalists or even NGOs. This follow-up paper thus continues to expose alternatives to the dominant view in each thematic area. We introduce Celeste Condit’s NeoGramscian depiction of the subordinate or “unrepresented groups,” who in the name of “laws” of justice and through limited (because of the obvious danger) “civic support” dare to contest the dominant ideology. This ideology of Rwandan genocide has become a commodity marketed to the media, so much so that the non-dominant ideology of a civil war is suppressed. Then we adopt Dana Cloud’s NeoGramscian model that emphasizes the oppressive structural relations in the commodification, both economically and ideologically. -

Court of Remorse Inside the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

Court of Remorse Critical Human Rights Series Editors Steve J. Stern Scott Straus Books in the series Critical Human Rights emphasize research that opens new ways to think about and understand human rights. The series values in particular empirically grounded and intellectually open research that eschews simplified accounts of human rights events and processes. In Court of Remorse, Thierry Cruvellier offers a nuanced and complex under- standing of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, a central post– Cold War human rights institution that helped to establish a now common pattern of creating justice mechanisms to account for past human rights atroc- ities. The atrocity in question is the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in which more than half a million civilians were killed. Cruvellier is one of the most knowl- edgeable outside observers of the court, having watched proceedings and interviewed key actors day after day for nearly a decade. In Court of Remorse, Cruvellier draws on these daily observations to render a subtle, eloquent, and intelligent account of the tribunal, and in so doing he helps us understand a critical human rights institution in new and profound ways. Court of Remorse Inside the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Thierry Cruvellier Translated by Chari Voss The University of Wisconsin Press Publication of this volume has been made possible, in part, through support from the A F C L S at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059 uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street London WCE 8LU, England eurospanbookstore.com Originally published as Le tribunal des vaincus: Un Nuremberg pour le Rwanda? Copyright © 2006 by Calmann-Lévy Translation copyright © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. -

Consensual Democracy in the Post -Genocide Rwanda: Evaluating the March 2001 District Elections

"CONSENSUAL DEMOCRACY" IN POST-GENOCIDE RWANDA EVALUATING THE MARCH 2001 DISTRICT ELECTIONS 9 October 2001 Africa report N°34 Nairobi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS.....................................................................i I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................5 II. CONFLICTING ELECTION OBJECTIVES: DECENTRALISATION AND CONSOLIDATION OF RPF POWER............................................................................................3 A. RPF POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY: TEACHING DEMOCRACY AND NATIONAL UNITY AND IDENTIFYING THE “WISE MEN”.............................................................................................................................................3 B. BREAKING THE GENOCIDAL MACHINERY.................................................................................................5 C. PREPARING FOR THE 2003 NATIONAL ELECTIONS AND BEYOND .............................................................6 III. EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL CONSTRAINTS..........................................................................8 A. THE REGIONAL INSECURITY TRAP ............................................................................................................8 B. INTERNAL POLITICAL TENSIONS...............................................................................................................9 C. THE CHALLENGE OF LIMITED RESOURCES................................................................................................9 -

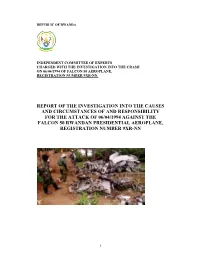

Report of the Investigation Into the Causes and Circumstances of And

REPUBLIC OF RWANDA INDEPENDENT COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS CHARGED WITH THE INVESTIGATION INTO THE CRASH ON 06/04/1994 OF FALCON 50 AEROPLANE, REGISTRATION NUMBER 9XR-NN. REPORT OF THE INVESTIGATION INTO THE CAUSES AND CIRCUMSTANCES OF AND RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ATTACK OF 06/04/1994 AGAINST THE FALCON 50 RWANDAN PRESIDENTIAL AEROPLANE, REGISTRATION NUMBER 9XR-NN 1 MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION 5 History and Mandate of the Committee 5 Methodology used 6 Political context prior to the attack of 06 April 1994 9 SECTION ONE: THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE PLANNED ATTACK 17 AND ITS EXECUTION The revelation of a plot targeting the imminent assassination of President 18 Habyarimana before the attack against his aeroplane Intelligence announced by the leaders of Hutu Power 18 Intelligence known by Rwandan military circles 22 Intelligence known by president Habyarimana and foreign sources 25 The organisation and issues of the Dar es Salaam Summit 28 Settlement of the political deadlock prevailing in Rwanda 28 Pressure on president Habyarimana before the Summit 28 Instability in Burundi: the main subject of the Dar es Salaam Summit 29 Questions surrounding the journey of the chief of staff of the Rwandan army 30 The proceedings of the Summit and circumstances of the return flight of the Falcon 50 35 Execution of the attack and its repercussions 29 The absence of an investigation into the attack 40 Questions about the voice recorder known as the “Black Box” 42 Information published soon after the attack: the black box in France -

(Un)Believable Truth About Rwanda Nicki Hitchcott ABSTRACT Since

The (Un)Believable Truth about Rwanda Nicki Hitchcott ABSTRACT Since the Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, a proliferation of fictional and non- fictional narratives has appeared, many of them claiming to represent the truth about what really happened in 1994. These include a small but significant number of Rwandan- authored novels which, this article suggests, invite the reader to accept what I call a “documentary pact”. While there is no single version of the truth about what happened in Rwanda, one of the common features of fictional responses to the genocide is an emphasis on truth claims. Drawing on examples of both fictional and non-fictional responses to the genocide, this essay discusses the implications of Rwandan authors’ insistence on the veracity of narratives that are sometimes difficult to believe. Emphasizing the importance for Rwandan writers, particularly survivors, of eliciting empathy from their readers, this essay will show that the documentary pact is an effective means of appealing to our shared human experience. KEYWORDS Rwanda; Genocide; Tutsi; Truth; Belief; Documentary; Fiction The (Un)Believable Truth about Rwanda Nicki Hitchcott Introduction In Boubacar Boris Diop’s 2001 novel, Murambi, le livre des ossements, a fictional Rwandan genocide survivor Gérard Nayinzira tells the protagonist, Cornelius, about the time he saw a militiaman raping a woman under a tree. During the rape, the commander of the militia passes by and crudely teases the young man: “Hé toi, Simba, partout où on va, c’est toujours la même chose, les femmes d’abord, les femmes, les femmes! Dépêche-toi de finir tes pompes, on a promis à Papa de bien faire le travail!” After walking on a few steps, the commander turns back on his heels, picks up a large stone and crushes the woman’s head. -

Please Retain Original Order

-- ----~ ~~------- ------ --- CODE CA BLESS- OUTG-01 "-'G- l 2 ;:JA r-J - l/ A PI<.. l99 G3 ltv\\ R. ~ - ------~-------- - [_ '2- S Ttl.\ ¢.T'-Y Co,..J F t c:>e. t-JTl A L- J UN ARCHIVES PLEASE RETAIN • SERIES s-112-0 ORIGINAL ORDER BOX ~5 FILE ACC. 1'14&/o"L/3 ·- . ' ') ,, RECEtVED (TWO) PRIORITY I 'J ,Ji I 8 p b: I 5 RESTRICTED OUTGOING FAX NO: A - 2/GP No V1 DTG: 18 JA.~.'VUARY 1996 TO: AS PER DISTRIBUTION FROM: SITUATION CENTRE UNHQ-DPKO 'i FAX NO: 9-011-331-4306-7o41 F.U NO: (212)·963-9053 (PLAIN) 3-3090 (212}-963-9852(CRYPTO) ~OBJECT: SITUATION CENTRE DATI..Y REPORT FOR lJNAMlR / ) '• !l A1N: FORCE CO.l\Il\1A1'41>ER UN.. <\MIR DRAFTER: MR. ZOUAlN CHIEF OF UNESCO I d I ~ / .-=-7 ~v-( ~ ,...,.~· •"" - I I I TOTAL 'N1Jl'vfBER OF TRANSMIITED PAGES INClUDING THIS PAGE: d._ 1. PLE.A-SE FIND THE DAILY tTNAMIR REPORT PRODUCED BY THE SITUATION C~!RE. Z, REFER A.l\'"'\r QlJESTIONS TO THE DUTY ROOM CLERK ON 3-2690. REGARDS. / \/v- Re~u le 1 9 JAN. 1996 1 l H : I ~ :; .,.,."~ ...~ . tl, G A l I • H v. A '< '' I.. FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY- NO FURTHER DlSSEMlNATION DPKO SITUATION CENTRE REPORT lJNAMIR- RWANDA Time: 6800 Hours NYT 18 January 1996 HIGHLIGHTS • The Secre1ary-General called for a '"major initiativet• to avert etlro.ic tragedy in Bur.mdi. POUTI CAL On 17 January, the Belgian parliamentary committee adopted a draft law, to allow a request to transfer three me:n suspected of involvement in Rwanda's genocid:.