Diets for a Better Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans Session 2 Assessment Background Information Tips Goals Vegetables, Fruit, Assessment of Whole Grains, Current Eating Habits and Beans On an average DAY, how many servings of these Could be Needs to foods do you eat or drink? Desirable improved be improved 1. Greens and non-starchy vegetables like collard, 4+ 2-3 0-1 mustard, or turnip greens, salads made with dark- green leafy lettuces, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, carrots, okra, zucchini, squash, turnips, onions, cabbage, spinach, mushrooms, bell peppers, or tomatoes (including tomato sauce) 2. Fresh, canned (in own juice or light syrup), or 3+ 1-2 0 frozen fruit or 100% fruit juice (½ cup of juice equals a serving) 3a. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Never Some Most of with white flour of the time the time 3b. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Most Some Never with whole wheat flour of the time of the time In an average WEEK, how many servings of these foods do you eat? 4. Starchy vegetables like acorn squash, butternut 4-7 2-3 0-1 squash, beets, green peas, sweet potatoes, or yams (do not include white potatoes) 5. White potatoes, including French fries and 1 or less 2-3 4+ potato chips 6. Beans or peas like pinto beans, kidney beans, 3+ 1-2 0 black beans, lentils, butter or lima beans, or black-eyed peas Continued on next page Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, and Beans 19 Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, Assessment of and Beans Current Eating Habits In an average WEEK, how often or how many servings of these foods do you eat? 7a. -

Confounding Factors in Discussions About What We Should Eat to Decrease Climate Change and Ensure Sustainable Food for All, Now and in the Future

Discussion document being compiled for Climate Friendly Bradford on Avon (CFBoA). (To be completed.) Ros Edwards, Lead for the CFBoA Sustainable Food and Drink Group 30.07.2019 Draft (Vs 1.3) of Confounding Factors in discussions about what we should eat to decrease climate change and ensure sustainable food for all, now and in the future. What gets in the way of communication and clarity around the issues? Sections: 1. The complexity of the issues P. 2 2. The way that the carbon footprint (CFP) of food is measured 2 3. Difficulty squaring the circle 4 4. Emissions: getting things in perspective 9 • UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions 9 • Other emissions related to the UK food chain not reflected in these figures 11 • Biogenic methane: when does methane count as a greenhouse gas? 12 5. Beans and pulses 15 6. Health recommendations on red meat and some studies into adequate nutrient intake 16 7. Dietary inclusions and exclusions 19 • Opening up the discussion 20 • What about vegetarianism? 21 • What about veganism? 22 • What about pescetarianism? 25 • The beef question 25 • Lab meat 27 8. Grassland versus cropland foods: food security 30 9. What about carbon storage in the soil and the fertility of the soil? 31 10. Land Use 11. Biodiversity 12. Food loss and Food Waste 41 13. Bioenergy 14. Conclusions 1 1) The complexity of the issues. 2) The way that the carbon footprint (CFP) of food is measured. This issue confounds all. It seems that the measures used to assess the carbon footprint almost always show that more intensively produced food is associated with a lower carbon footprint, which leads to a strong suspicion that many factors are not being taken into account. -

Eating for 2 Degrees New and Updated Livewell Plates Summary Report © J Oh N D a I E Ls / WWF

EATING FOR 2 DEGREES NEW AND UPDATED LIVEWELL PLATES SUMMARY REPORT © J OH N D A N I E LS / WWF Cover photo © Kelly Sillaste / Getty Images / WWF Contributors Gerard Kramer, Bart Durlinger, Lody Kuling, Willem-Jan van Zeist, Hans Blonk, Roline Broekema, Sarah Halevy Design madenoise.com CONTENTS May 2017 FOREWORD .............................................................................................4 About WWF KEY FINDINGS ........................................................................................6 WWF is the world’s leading independent conservation organisation. We’re CAll TO ACTION ...................................................................................7 creating solutions to the most important environmental challenges facing the WHAT WE SET OUT TO DO ...............................................................8 planet. We work with communities, businesses and governments in over METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................9 100 countries to help people and nature thrive. Together, we’re safeguarding the LIVEWell PRINCIPLES .................................................................... 10 natural world, tackling dangerous climate change and enabling people to use only ADULT 2020 PlATE ...........................................................................11 their fair share of natural resources. ADULT 2030 PlATE .......................................................................... 12 Food is at the heart of many key environmental issues -

Healthy Eating Continued…

Whole Grain, Plant-based Lifestyle What is a Whole Grain, Plant-based Lifestyle (WGPB)? This type of lifestyle involves the elimination of all animal-based products, including meat, dairy and eggs. Also included in the diet are unprocessed or minimally processed grains. Although, similar to a vegan diet, it is not the same. There are different motivations behind adopting such a lifestyle. A WGPB lifestyle focuses on plants, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, seeds and nuts. One of the main reasons to choose this lifestyle is the many health benefits. It can assist with weight-loss since it is full of fiber and high water content, which causes you to feel full sooner. Additionally, studies have shown that individuals who adhere to a WGPB diet have improved blood glucose levels. Therefore, those who are diabetic can decrease their need for medications. What are some other benefits? Plant-based foods are loaded with healthy fats, vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals which improve skin clarity. Vitamin C, for instance, is a great antioxidant that can be found in foods such as; broccoli, papaya, apricot, and bell peppers. They assist in stimulating collagen production, smoothing lines and reducing wrinkles. As a result of the elimination of processed foods, sugars and flour, individuals have found an increase in energy due to decreased spikes in sugar levels. A WGPB diet consists of a clean source of protein, carbohydrates and fruits that help sustain a natural energy level. Another benefit is the increase in our gut’s natural flora, the bacteria that creates a healthy microbiome. -

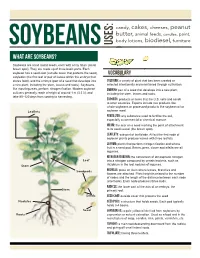

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Development and Validation of an Index Based on EAT-Lancet Recommendations: the Planetary Health Diet Index

nutrients Article Development and Validation of an Index Based on EAT-Lancet Recommendations: The Planetary Health Diet Index Leandro Teixeira Cacau 1 , Eduardo De Carli 1 , Aline Martins de Carvalho 1 , Paulo Andrade Lotufo 2, Luis A. Moreno 3,4,5 , Isabela Martins Bensenor 2 and Dirce Maria Marchioni 1,* 1 Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, University of São Paulo, São Paulo 01246-904, Brazil; [email protected] (L.T.C.); [email protected] (E.D.C.); [email protected] (A.M.d.C.) 2 Clinical and Epidemiological Research Center, University Hospital, University of São Paulo, São Paulo 05508-000, Brazil; [email protected] (P.A.L.); [email protected] (I.M.B.) 3 Growth, Exercise, Nutrition and Development (GENUD) Research Group, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Zaragoza, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain; [email protected] 4 Instituto Agroalimentario de Aragón (IA2), Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Aragón, 50013 Zaragoza, Spain 5 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBEROBN), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, 28040 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The EAT-Lancet Commission has proposed a planetary health diet. We propose the development of the Planetary Health Diet Index (PHDI) based on this proposed reference diet. We used baseline dietary data obtained through a 114-item FFQ from 14,779 participants of the Longitudinal Study on Adult Health, a multicenter cohort study conducted in Brazil. The PHDI has 16 components and a score from 0 to 150 points. Validation and reliability analyses were performed, Citation: Cacau, L.T.; De Carli, E.; de including principal component analyses, association with selected nutrients, differences in means Carvalho, A.M.; Lotufo, P.A.; Moreno, between groups (for example, smokers vs. -

M E D I a R E L E A

M E D I A R E L E A S E Grains & Legumes Nutrition Council, Level 1, 40 Mount Street, North Sydney, NSW 2060 Ph: (02) 9394 8661 Web: www.glnc.org.au GOT MYLK? NEW AUDIT SHINES LIGHT ON THE GROWING MILK ALTERNATIVES CATEGORY 4 October 2018 A new audit of plant-based milk alternatives in Australia has revealed the category has grown by a staggering 58% in number of products in two years, but health professionals are alerting Australians that not all ‘mylks’ are nutritionally equal. Carried out by the Grains & Legumes Nutrition Council (GLNC), the audit of 112 products on shelf in the four major supermarkets included nut milks, grain milks (e.g. oat, rice), legume milks (e.g. soy, pea), coconut milks and mixes, and reviewed all on-pack nutrition information. Since the last audit of its kind in 2016, the number of coconut milk products has more than doubled (+220%), nut milks have increased by 90%, with even the well-established legume milk category growing by 36%. But compared to dairy milk, GLNC’s Nutrition Manager Felicity Curtain said some plant-based milks don’t stack up nutritionally, with many falling short on valuable calcium and protein. “30% of products did not mention calcium on-pack, suggesting they weren’t fortified with the important mineral. While those that were fortified had consistent amounts, it highlights the importance of checking labels to be confident in the choice you’re making.” According to Accredited Practising Dietitian Joel Feren, achieving equivalence in terms of calcium content should be a focus for industry. -

Soy Free Diet Avoiding Soy

SOY FREE DIET AVOIDING SOY An allergy to soy is common in babies and young children, studies show that often children outgrow a soy allergy by age 3 years and the majority by age 10. Soybeans are a member of the legume family; examples of other legumes include beans, peas, lentils and peanut. It is important to remember that children with a soy allergy are not necessarily allergic to other legumes, request more clarification from your allergist if you are concerned. Children with a soy allergy may have nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, difficulty breathing, and or a skin reaction after eating or drinking soy products. These symptoms can be avoided by following a soy free diet. What foods are not allowed on a soy free diet? Soy beans and edamame Soy products, including tofu, miso, natto, soy sauce (including sho yu, tamari), soy milk/creamer/ice cream/yogurt, soy nuts and soy protein, tempeh, textured vegetable protein (TVP) Caution with processed foods - soy is widely used manufactured food products – remember to carefully read labels. o Soy products and derivatives can be found in many foods, including baked goods, canned tuna and meat, cereals, cookies, crackers, high-protein energy bars, drinks and snacks, infant formulas, low- fat peanut butter, processed meats, sauces, chips, canned broths and soups, condiments and salad dressings (Bragg’s Liquid Aminos) USE EXTRA CAUTION WITH ASIAN CUISINE: Asian cuisine are considered high-risk for people with soy allergy due to the common use of soy as an ingredient and the possibility of cross-contamination, even if a soy-free item is ordered. -

Promoting Sustainable Food Systems in Mediterranean Countries

Promoting sustainable food systems in Mediterranean countries: a framework to implement recommendations and actions Marie Josephe Amiot-Carlin, Marlène Perignon, Nicole Darmon, Sophie Drogue, Carole Sinfort, Eric Verger, Jalila El Ati, . The Medina-Study Group To cite this version: Marie Josephe Amiot-Carlin, Marlène Perignon, Nicole Darmon, Sophie Drogue, Carole Sinfort, et al.. Promoting sustainable food systems in Mediterranean countries: a framework to implement recommen- dations and actions. Development of voluntary guidelines for the sustainability of the Mediterranean diet in the Mediterranean region, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). ITA.; International Cen- tre for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies (CIHEAM). INT., Mar 2017, Bari, Italy. 141 p. hal-01595254 HAL Id: hal-01595254 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01595254 Submitted on 2 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Technical Workshop Development of voluntary -

T. Colin Campbell, Ph.D. Thomas M. Campbell II

"Everyone in the field of nutrition science stands on the shoulders of Dr. Campbell, who is one of the giants in the field. This is one of the most important books about nutrition ever written - reading it may save your life." - Dean Ornish, MD THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF NUTRITION EVER CONDUCTED --THE-- STARTLING IMPLICATIONS FOR DIET, WEIGHT Loss AND LONG-TERM HEALTH T. COLIN CAMPBELL, PHD AND THOMAS M. CAMPBELL II FOREWORD BY JOHN ROBBINS, AUTHOR, DIET FOR A NEW AMERICA PRAISE FOR THE CHINA STUDY "The China Study gives critical, life-saving nutritional information for ev ery health-seeker in America. But it is much more; Dr. Campbell's expose of the research and medical establishment makes this book a fascinating read and one that could change the future for all of us. Every health care provider and researcher in the world must read it." -JOEl FUHRMAN, M.D. Author of the Best-Selling Book, Eat To Live . ', "Backed by well-documented, peer-reviewed studies and overwhelming statistics the case for a vegetarian diet as a foundation for a healthy life t style has never been stronger." -BRADLY SAUL, OrganicAthlete.com "The China Study is the most important book on nutrition and health to come out in the last seventy-five years. Everyone should read it, and it should be the model for all nutrition programs taught at universities, The reading is engrossing if not astounding. The science is conclusive. Dr. Campbells integrity and commitment to truthful nutrition education shine through." -DAVID KLEIN, PublisherlEditor Living Nutrition MagaZine "The China Study describes a monumental survey of diet and death rates from cancer in more than 2,400 Chinese counties and the equally monu mental efforts to explore its Significance and implications for nutrition and health. -

Whole Grain Choices Everywhere America Eats

Program Schedule Whole Grain Choices Speaker Roster & Abstracts Everywhere America Eats Whole Grain Momentum Whole Grains in Restaurants & Schools Whole Grains and Health An International Conference jointly organized by The Whole Grains Council and Oldways The Whole Grains Council November 5-7, 2007 • Kansas City Attendee Roster Sponsors & Acknowledgements Program Schedule 4:45-5:15 Whole Grains: Dietary Recommendations and Intake Patterns Robert Post, PhD, Deputy Director, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (CNPP) / United Stated Department of Agriculture (USDA) 5:15-5:45 Why Whole Grains Matter For Health David R. Jacobs, Jr., PhD, Professor, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota School of Public Health 6:00-7:30 Welcoming Reception and Exhibits On Your Own Whole Grains Dine-Around in local restaurants Tuesday, November 6 WHAT Factors Influence Consumers’ Food Choices Session II: 7:00 – 10:45 7:00-8:30 Continental Breakfast and Exhibits 8:30-8:40 Introduction and Outline of the Day 8:40-9:00 How Food Decisions Are Made Shelley Goldberg, MPH, RD, Director, Nutrition Communications, International Food Information Council 9:00-9:20 Trends In Consumer Food Habits and Behaviors Kate Peringer, Marketing Communications Manager, The Hartman Group 9:20-9:45 Questions and Answers 9:45-10:15 Coffee break with Exhibits 3 10:15-10:45 Panel: Where Americans Eat Molly Gise, Online Associate Managing Editor, Nation’s Restaurant News Michael Birchenall, Editor and Publisher, Foodservice Monthly Erica Bohm, MS, Vice President and Director of Strategic Partnerships, HealthyDiningFinder.com Session III: 10:45 – 1:00 WHERE Whole Grains Fit Into Today’s Lifestyle 10:45-12:00 A Rapid-fire “Iron Chef” Cook-off Two top chefs demonstrate that whole grains are quick, easy and delicious. -

Scientific Update on Plant-Based Eating and Cardiometabolic Health

2020 SCIENTIFIC UPDATE ON PLANT-BASED EATING AND CARDIOMETABOLIC HEALTH Authors: Hana Kahleova, MD, PhD; Nerea Becerra-Tomas, RD, PhD; Sonia Blanco Mejia, MD, MSc; Andrea J Glenn, MSc, RD; Stephanie De Vriese, PhD; David JA Jenkins, MD, PhD; Cyril WC Kendall PhD; Jordi Salas-Salvadó, MD, PhD; John L Sievenpiper MD, PhD September 2020 Affiliations of the authors: Hana Kahleova 1, MD, PhD; Nerea Becerra-Tomas 2-3, RD, PhD; Sonia Blanco Mejia 4-5, MD, MSc; Andrea J Glenn 4-5, MSc, RD; Stephanie De Vriese 6, PhD; David JA Jenkins 4-5, MD, PhD; Cyril WC Kendall 4-5 PhD; Jordi Salas-Salvadó 2-3, MD, PhD; John L Sievenpiper 4-5 MD, PhD 1 Department of Medicine, Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, Washington, DC, USA. 2 Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Human Nutrition Unit, Pere Virgili Institute for Health Research (IISPV), University Hospital of Sant Joan de Reus, Rovira i Virgili University, Reus, Spain 3 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y la Nutrición (CIBEROBN), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain 4 St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Canada 5 Department of Nutritional Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada 6 Alpro Foundation; Ghent, Belgium This review is fully supported by the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Alpro Foundation: Harry Aiking (VU University Amsterdam); Anna Arnoldi (University Milano); Christine Debeuf (Alpro); Peter Clarys (Vrije Universiteit Brussel); Helmut Heseker (University Paderborn); Sander Kersten (University Wageningen); Ian Rowland (University Reading); Cesare Sirtori (University Milano); Bregt Uyttenhove (Alpro) and Kurt Widhalm (University Vienna) Date: September 2020 2 CONTENT Global Health Burden of Cardiometabolic Disease........................................................................................................................