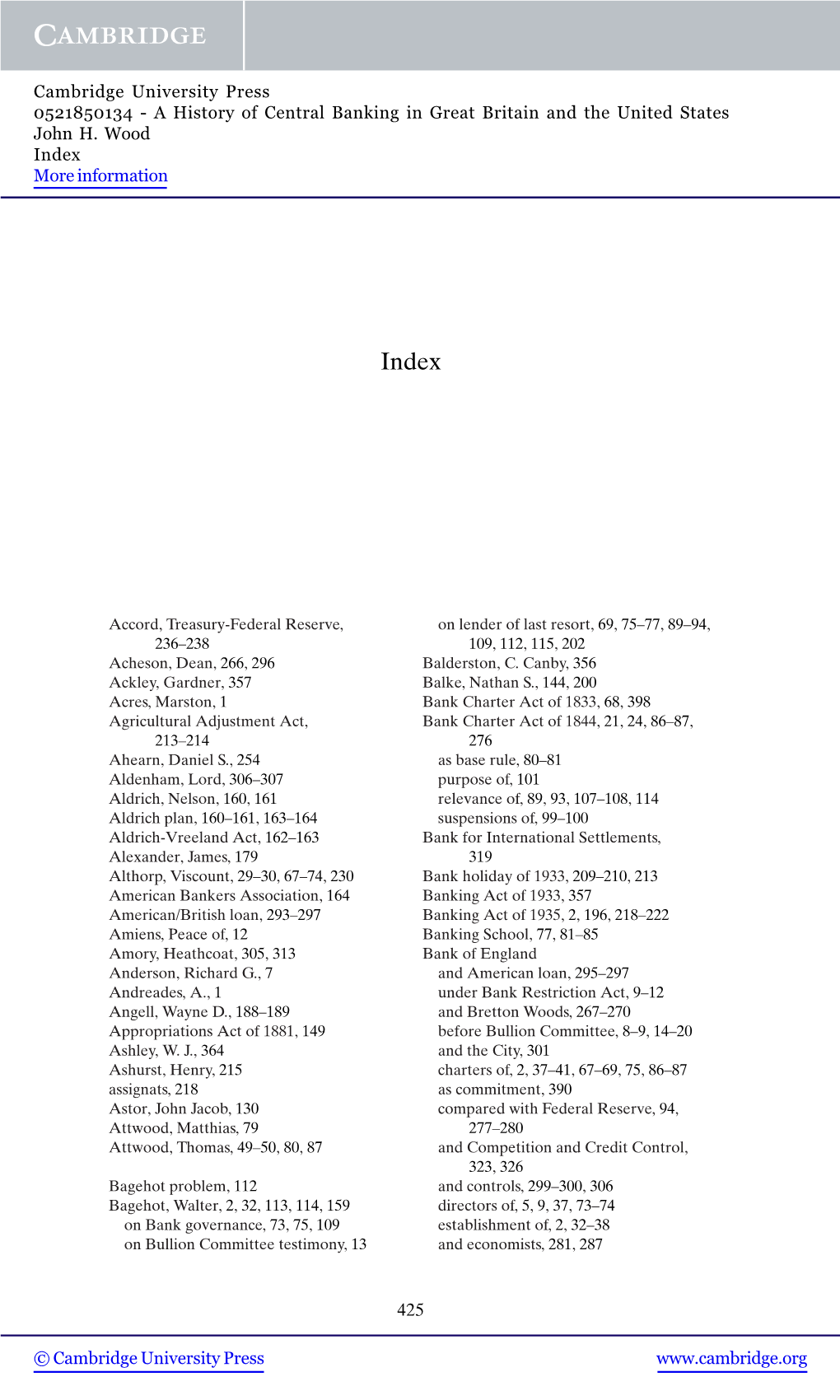

9780521850131 Index.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculated for the Use of the State Of

3i'R 317.3M31 H41 A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of IVIassachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1839amer MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER, AND mmwo states ©alrntiar, 1839. ALSO CITY OFFICERS IN BOSTON, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JAMES LORING, 13 2 Washington Street. ECLIPSES IN 1839. 1. The first will be a great and total eclipse, on Friday March 15th, at 9h. 28m. morning, but by reason of the moon's south latitude, her shadow will not touch any part of North America. The course of the general eclipse will be from southwest to north- east, from the Pacific Ocean a little west of Chili to the Arabian Gulf and southeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The termination of this grand and sublime phenomenon will probably be witnessed from the summit of some of those stupendous monuments of ancient industry and folly, the vast and lofty pyramids on the banks of the Nile in lower Egypt. The principal cities and places that will be to- tally shadowed in this eclipse, are Valparaiso, Mendoza, Cordova, Assumption, St. Salvador and Pernambuco, in South America, and Sierra Leone, Teemboo, Tombucto and Fezzan, in Africa. At each of these places the duration of total darkness will be from one to six minutes, and several of the planets and fixed stars will probably be visible. 2. The other will also be a grand and beautiful eclipse, on Satur- day, September 7th, at 5h. 35m. evening, but on account of the Mnon's low latitude, and happening so late in the afternoon, no part of it will be visible in North America. -

Against Regulatory Stimulus

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2020 Against Regulatory Stimulus Erik F. Gerding University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Banking and Finance Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, and the Legislation Commons Citation Information Erik F. Gerding, Against Regulatory Stimulus, 83 LAW & CONTEMP. PROBS. 49 (2020), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1268. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK PROOF -G ERDING (DO NOT DELETE) 3/1/2020 10:34 PM AGAINST REGULATORY STIMULUS ERIK F. GERDING* I INTRODUCTION The 2012 JOBS Act1 deserves close scrutiny not only because of its impact on federal securities laws, but because it represented an attempt by Congress to use deregulation as a macroeconomic tool to jumpstart growth. When enacted in 2012, the U.S. economy was still struggling to recover from the global financial crisis. After the crisis, traditional macroeconomic tools were either rendered ineffective or appeared politically infeasible. Interest rates were already close to zero, and fears grew that global economies had entered a “liquidity trap.”2 Meanwhile, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives consistently blocked Democrats’ fiscal spending initiatives. -

The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 159–181 The Real Bills Views of the Founders of the Fed Robert L. Hetzel ilton Friedman (1982, 103) wrote: “In our book on U.S. mon- etary history, Anna Schwartz and I found it possible to use M one sentence to describe the central principle followed by the Federal Reserve System from the time it began operations in 1914 to 1952. That principle, to quote from our book, is: ‘Ifthe ‘money market’ is properly managed so as to avoid the unproductive use of credit and to assure the availability of credit for productive use, then the money stock will take care of itself.’” For Friedman, the reference to “the money stock”was synonymous with “the price level.”1 How did American monetary experience and debate in the 19th century give rise to these “real bills” views as a guide to Fed policy in the pre-World War II period? As distilled in the real bills doctrine, the founders of the Fed under- stood the Federal Reserve System as a decentralized system of reserve depositories that would allow the expansion and contraction of currency and credit based on discounting member-bank paper that originated out of productive activity. By discounting these “real bills,”the short- term loans that …nanced trade and goods in the process of production, policymakers ful…lled their responsibilities as they understood them. That is, they would provide the reserves required to accommodate the “legitimate,” nonspeculative, demands for credit.2 In so doing, they The author acknowledges helpful comments from Huberto Ennis, Motoo Haruta, Gary Richardson, Robert Sharp, Kurt Schuler, Ellis Tallman, and Alexander Wolman. -

Chapter 28 | Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation 635 28 | Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation

Chapter 28 | Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation 635 28 | Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation Figure 28.1 Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve Headquarters, Washington D.C. Some of the most influential decisions regarding monetary policy in the United States are made behind these doors. (Credit: modification of work by “squirrel83”/Flickr Creative Commons) The Problem of the Zero Percent Interest Rate Lower Bound Most economists believe that monetary policy (the manipulation of interest rates and credit conditions by a nation’s central bank) has a powerful influence on a nation’s economy. Monetary policy works when the central bank reduces interest rates and makes credit more available. As a result, business investment and other types of spending increase, causing GDP and employment to grow. But what if the interest rates banks pay are close to zero already? They cannot be made negative, can they? That would mean that lenders pay borrowers for the privilege of taking their money. Yet, this was the situation the U.S. Federal Reserve found itself in at the end of the 2008–2009 recession. The federal funds rate, which is the interest rate for banks that the Federal Reserve targets with its monetary policy, was slightly above 5% in 2007. By 2009, it had fallen to 0.16%. The Federal Reserve’s situation was further complicated because fiscal policy, the other major tool for managing the economy, was constrained by fears that the federal budget deficit and the public debt were already too high. What were the Federal Reserve’s options? How could monetary policy be used to stimulate the economy? The answer, as we will see in this chapter, was to change the rules of the game. -

Financial Panics and Scandals

Wintonbury Risk Management Investment Strategy Discussions www.wintonbury.com Financial Panics, Scandals and Failures And Major Events 1. 1343: the Peruzzi Bank of Florence fails after Edward III of England defaults. 2. 1621-1622: Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire debases coinage during the Thirty Years War 3. 1634-1637: Tulip bulb bubble and crash in Holland 4. 1711-1720: South Sea Bubble 5. 1716-1720: Mississippi Bubble, John Law 6. 1754-1763: French & Indian War (European Seven Years War) 7. 1763: North Europe Panic after the Seven Years War 8. 1764: British Currency Act of 1764 9. 1765-1769: Post war depression, with farm and business foreclosures in the colonies 10. 1775-1783: Revolutionary War 11. 1785-1787: Post Revolutionary War Depression, Shays Rebellion over farm foreclosures. 12. Bank of the United States, 1791-1811, Alexander Hamilton 13. 1792: William Duer Panic in New York 14. 1794: Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania (Gallatin mediates) 15. British currency crisis of 1797, suspension of gold payments 16. 1808: Napoleon Overthrows Spanish Monarchy; Shipping Marques 17. 1813: Danish State Default 18. 1813: Suffolk Banking System established in Boston and eventually all of New England to clear bank notes for members at par. 19. Second Bank of the United States, 1816-1836, Nicholas Biddle 20. Panic of 1819, Agricultural Prices, Bank Currency, and Western Lands 21. 1821: British restoration of gold payments 22. Republic of Poyais fraud, London & Paris, 1820-1826, Gregor MacGregor. 23. British Banking Crisis, 1825-1826, failed Latin American investments, etc., six London banks including Henry Thornton’s Bank and sixty country banks failed. -

Inflation and Other Risks of Unsound Money

Inflation and Other Risks of Unsound Money Prepared by Martin Hickling Presented to the Actuaries Institute Actuaries Summit 20-21 May 2013 Sydney This paper has been prepared for Actuaries Institute 2013 Actuaries Summit. The Institute Council wishes it to be understood that opinions put forward herein are not necessarily those of the Institute and the Council is not responsible for those opinions. copyright Martin Hickling The Institute will ensure that all reproductions of the paper acknowledge the Author/s as the author/s, and include the above copyright statement. Institute of Actuaries of Australia ABN 69 000 423 656 Level 7, 4 Martin Place, Sydney NSW Australia 2000 t +61 (0) 2 9233 3466 f +61 (0) 2 9233 3446 e [email protected] w www.actuaries.asn.au Inflation and Other Risks of Unsound Money Purpose of paper To investigate Austrian economic literature and explain to an actuarial audience the concepts of ‘sound money’ (normally a commodity based medium of exchange) and the risks, including inflation, of the current ‘unsound’ government-issued fiat based money system. Abstract No form of money is perfect. Even gold suffers from new supply – although it is quite difficult and costly to mine. Austrian economic theory helps us to understand the distortions and ultimate consequences of injections of government fiat paper money. As the new money is created it dilutes purchasing power of the holders of money - in a free market this is the people who have produced more than they have consumed - and reduces the real value of holders of nominal debts. -

Monetary Circuit and Real Transmission Channels of Financial

Munich Personal RePEc Archive International Trade and Real Transmission Channels of Financial Shocks in Globalized Production Networks Escaith, Hubert and Gonguet, Fabien World Trade Organization - ERSD May 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/15558/ MPRA Paper No. 15558, posted 05 Jun 2009 12:20 UTC Staff Working Paper ERSD-2009-06 May 2009 World Trade Organization Economic Research and Statistics Division International Trade and Real Transmission Channels of Financial Shocks in Globalized Production Networks Hubert Escaith: WTO Fabien Gonguet: École Polytechnique-ENSAE, Paris Manuscript date: May 2009 Disclaimer: This is a working paper, and hence it represents research in progress. This paper represents the opinions of the authors, and is the product of professional research. It is not meant to represent the position or opinions of the WTO or its Members, nor the official position of any staff members. Any errors are the fault of the authors. Copies of working papers can be requested from the divisional secretariat by writing to: Economic Research and Statistics Division, World Trade Organization, Rue de Lausanne 154, CH 1211 Geneva 21, Switzerland. Please request papers by number and title. International Trade and Real Transmission Channels of Financial Shocks in Globalized Production Networks Hubert Escaith * 1 Fabien Gonguet ** Abstract: The article analyses the role of international supply chains as transmission channels of a financial shock. Because individual firms are interdependent and rely on each other, either as supplier of intermediate goods or client for their own production, an exogenous financial shock affecting a single firm, such as the termination of a line of credit, reverberates through the productive chain. -

Economic Quarterly, Second Quarter 2014, Vol. 100, No. 2

Economic Quarterly— Volume 100, Number 2— Second Quarter 2014— Pages 87–111 Flows To and From Working Part Time for Economic Reasons and the Labor Market Aggregates During and After the 2007{09 Recession Maria E.Canon,Marianna Kudlyak, Guannan Luo, and Marisa Reed hile the unemployment rate is one of the most cited eco- nomic indicators, economists and policymakers also exam- W ine a wide array of other indicators to gauge the health of the U.S. labor market. One such indicator is the U-6 index, an extended measure of the unemployment rate published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In addition to unemployed workers, the U-6 index in- cludes individuals who are working part time for economic reasons and individuals who are out of the labor force but are marginally attached to the labor market. Individuals are classi…ed as working part time for economic reasons (henceforth, PTER) if they work fewer than 35 hours per week, want to work full time, and cite “slack business conditions”1 Canon is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Luo is an assistant professor at the City University of Hong Kong. Kudlyak is an economist and Reed is a research associate at the Federal Re- serve Bank of Richmond. The authors are very grateful to Alex Wolman, Felipe Schwartzman, Christian Matthes, and Peter Debbaut for useful com- ments and suggestions. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not re‡ect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. -

The Suffolk Bank and the Panic of 1837: How a Private Bank Acted As a Lender-Of-Last-Resort*

The Suffolk Bank and the Panic of 1837: How a Private Bank Acted as a Lender-of-Last-Resort* Arthur J. Rolnick Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Bruce D. Smith University of Texas at Austin and Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Warren E. Weber Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and University of Minnesota Abstract Before the establishment of federal deposit insurance, the U.S. experienced periodic banking panics, during which banks suspended specie payments and reduced lending. There was often a corresponding economic slowdown. The Panic of 1837 is considered one of the worst banking panics, and it coincided with a slowdown that lasted for almost five years. The economic disruption was not uniform across the country, however. The slowdown in New England was substantially less severe than elsewhere. Here we suggest that the Suffolk Bank, a private bank, was one reason for New England’s relative success. We argue that the Suffolk Bank’s provision of note-clearing and lender-of-last-resort services (via the Suffolk Banking System) lessened the effects of the Panic of 1837 in New England relative to the rest of the country, where no bank provided such services. * The authors thank the Baker Library, Harvard Business School for the materials provided from its Suffolk Bank Collection. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. 484 Arthur J. Rolnick, Bruce D. Smith, and Warren E. Weber Before the establishment of federal deposit insurance in 1935, the U.S. -

By:Bill Medley

By: Bill Medley Highways of Commerce Central Banking and The U.S. Payments System By: Bill Medley Highways of Commerce Central Banking and The U.S. Payments System Published by the Public Affairs Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City 1 Memorial Drive • Kansas City, MO 64198 Diane M. Raley, publisher Lowell C. Jones, executive editor Bill Medley, author Casey McKinley, designer Cindy Edwards, archivist All rights reserved, Copyright © 2014 Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the publisher. First Edition, July 2014 The Highways of Commerce • III �ontents Foreword VII Chapter One A Calculus of Chaos: Commerce in Early America 1 Chapter Two “Order out of Confusion:” The Suffolk Bank 7 Chapter Three “A New Era:” The Clearinghouse 19 Chapter Four “A Famine of Currency:” The Panic of 1907 27 Chapter Five “The Highways of Commerce:” The Road to a Central Bank 35 Chapter Six “A problem…of great novelty:” Building a New Clearing System 45 Chapter Seven Bank Robbers and Bolsheviks: The Par Clearance Controversy 55 Chapter Eight “A Plump Automatic Bookkeeper:” The Rise of Banking Automation 71 Chapter Nine Control and Competition: The Monetary Control Act 83 Chapter Ten The Fed’s Air Force: A Plan for the Future 95 Chapter Eleven Disruption and Evolution: The Development of Check 21 105 Chapter Twelve Banks vs. Merchants: The Durbin Amendment 113 Afterword The Path Ahead 125 Endnotes 128 Sources and Selected Bibliography 146 Photo Credits 154 Index 160 Contents • V ForewordAs Congress undertook the task of designing a central bank for the United States in 1913, it was clear that lawmakers intended for the new institution to play a key role in improving the performance of the nation’s payments system. -

The United States' Experience with State Bank Notes: Lessons for Regulating E-Cash*

• The United States' Experience with State Bank Notes: Lessons for Regulating E-Cash* Arthur J. Rolnick Bruce D. Smith Warren E. Weber Revised version January 1997 • Preliminary, do not cite or quote Comments invited The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. We thank Stacey Schreft and Ed Stevens for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. • • Right of regulating coin given to Congress for two reasons: For sake of uniformity; and to prevent fraud in States towards each other or foreigners. Both these reasons hold equally as to paper money. James Madison, 1786 We do not pretend, that a National Bank can establish and maintain a sound and uniform state of currency in the country, in spite of the National Government; but we do say that it has established and maintained such a currency, and can do so again, by the aid of that Government; and we further say, that no duty is more imperative on that Government, than the duty it owes the people, of furnishing them a sound and uniform currency. Abraham Lincoln, 1839 1. Introduction For well over a hundred years, the United States has benefited from having a safe and uniform currency. Since 1863, banks have been essentially prohibited from issuing notes that do not have the full backing of the federal government, and since 1879 virtually all currency has circulated at par. The possible introduction of privately-issued electronic monies has some people concerned that the situation could change, however. -

America's First Great Moderation Ryan Shaffer Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 America's First Great Moderation Ryan Shaffer Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Shaffer, Ryan, "America's First Great Moderation" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 280. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/280 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE “AMERICA’S FIRST GREAT MODERATION” SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR MARC WEIDENMIER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY RYAN SHAFFER FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2011 NOVEMBER 28, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. LITERATURE REVIEW . 3 III. DATA ANALYSIS . 9 IV. UNDERSTANDING THE FIRST GREAT MODERATION . 13 V. CONCLUSION . 28 DATA APPENDIX . 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 38 I. INTRODUCTION Current economic conventional wisdom indicates that the economy of the United States prior to the Civil War was unstable and fraught with recessions. The collapse of the Second Bank of the United States by Andrew Jackson’s hand left the United States without a central bank or lender of last resort, and many state banks produced their own banknotes for currency exchange. These different currencies made it difficult to unite interest rates across state lines, inhibiting interstate commerce, and banking panics in the antebellum period often led to declines in lending and investment that drove recessions. 1 The National Bureau of Economic Research, 2 the premier authority on business cycle dating, identifies five recessions in the two decades prior to the Civil War. By comparison, the period from 1984 to 2007, more commonly referred to as the Great Moderation, was unusually stable and productive.