(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0042146 A1 MMARAJU Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apiaceae) - Beds, Old Cambs, Hunts, Northants and Peterborough

CHECKLIST OF UMBELLIFERS (APIACEAE) - BEDS, OLD CAMBS, HUNTS, NORTHANTS AND PETERBOROUGH Scientific name Common Name Beds old Cambs Hunts Northants and P'boro Aegopodium podagraria Ground-elder common common common common Aethusa cynapium Fool's Parsley common common common common Ammi majus Bullwort very rare rare very rare very rare Ammi visnaga Toothpick-plant very rare very rare Anethum graveolens Dill very rare rare very rare Angelica archangelica Garden Angelica very rare very rare Angelica sylvestris Wild Angelica common frequent frequent common Anthriscus caucalis Bur Chervil occasional frequent occasional occasional Anthriscus cerefolium Garden Chervil extinct extinct extinct very rare Anthriscus sylvestris Cow Parsley common common common common Apium graveolens Wild Celery rare occasional very rare native ssp. Apium inundatum Lesser Marshwort very rare or extinct very rare extinct very rare Apium nodiflorum Fool's Water-cress common common common common Astrantia major Astrantia extinct very rare Berula erecta Lesser Water-parsnip occasional frequent occasional occasional x Beruladium procurrens Fool's Water-cress x Lesser very rare Water-parsnip Bunium bulbocastanum Great Pignut occasional very rare Bupleurum rotundifolium Thorow-wax extinct extinct extinct extinct Bupleurum subovatum False Thorow-wax very rare very rare very rare Bupleurum tenuissimum Slender Hare's-ear very rare extinct very rare or extinct Carum carvi Caraway very rare very rare very rare extinct Chaerophyllum temulum Rough Chervil common common common common Cicuta virosa Cowbane extinct extinct Conium maculatum Hemlock common common common common Conopodium majus Pignut frequent occasional occasional frequent Coriandrum sativum Coriander rare occasional very rare very rare Daucus carota Wild Carrot common common common common Eryngium campestre Field Eryngo very rare, prob. -

Evolutionary Shifts in Fruit Dispersal Syndromes in Apiaceae Tribe Scandiceae

Plant Systematics and Evolution (2019) 305:401–414 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-019-01579-1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evolutionary shifts in fruit dispersal syndromes in Apiaceae tribe Scandiceae Aneta Wojewódzka1,2 · Jakub Baczyński1 · Łukasz Banasiak1 · Stephen R. Downie3 · Agnieszka Czarnocka‑Cieciura1 · Michał Gierek1 · Kamil Frankiewicz1 · Krzysztof Spalik1 Received: 17 November 2018 / Accepted: 2 April 2019 / Published online: 2 May 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Apiaceae tribe Scandiceae includes species with diverse fruits that depending upon their morphology are dispersed by gravity, carried away by wind, or transported attached to animal fur or feathers. This diversity is particularly evident in Scandiceae subtribe Daucinae, a group encompassing species with wings or spines developing on fruit secondary ribs. In this paper, we explore fruit evolution in 86 representatives of Scandiceae and outgroups to assess adaptive shifts related to the evolutionary switch between anemochory and epizoochory and to identify possible dispersal syndromes, i.e., patterns of covariation of morphological and life-history traits that are associated with a particular vector. We also assess the phylogenetic signal in fruit traits. Principal component analysis of 16 quantitative fruit characters and of plant height did not clearly separate spe- cies having diferent dispersal strategies as estimated based on fruit appendages. Only presumed anemochory was weakly associated with plant height and the fattening of mericarps with their accompanying anatomical changes. We conclude that in Scandiceae, there are no distinct dispersal syndromes, but a continuum of fruit morphologies relying on diferent dispersal vectors. Phylogenetic mapping of ten discrete fruit characters on trees inferred by nrDNA ITS and cpDNA sequence data revealed that all are homoplastic and of limited use for the delimitation of genera. -

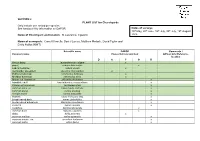

SECTION 2 PLANT LIST for Churchyards Only Include One

SECTION 2 PLANT LIST for Churchyards Only include one record per species See handout 9 for information on DAFOR Dates of surveys: 15th May, 20th June, 15th July, 30th July, 12th August Name of Churchyard and location: St Lawrence, Ingworth 2016 Name of surveyor/s: Cornell Howells, Daniel Lavery, Matthew Mcdade, David Taylor and Emily Nobbs (NWT) Scientific name DAFOR Comments / Common name Please tick relevant box GPS or Grid Reference location D A F O R Oxeye daisy leucanthemum vulgare x pignut conopodium majus x Lady’s bedstraw galium verum x Germander speedwell veronica chamaedrys x Bulbous buttercup ranunculus bulbosus x Meadow buttercup ranunculus acris x Mouse ear hawkweed pillosella officinarum x hybrid bluebell hyacinthoides x massartiana x Knapweed (common) centaurea nigra x common cat’s-ear hypochaeris radicata x common sorrel rumex acetosa x sheep’s sorrel rumex acetosella x bramble rubus fruticosus agg. x broad-leaved dock rumex obtusifolius x broad-leaved willowherb Epilobium montanum x cleavers galium aparine x cocksfoot dactylis glomerata x common bent Agrostis capillaris x daisy bellis perennis x common mallow malva sylvestris x common mouse ear cerastium fontanum x common nettle urtica dioica x common vetch vicia sativa x copper beech Fagus sylvatica f. purpurea x cow parsley anthriscus sylvestris x creeping buttercup ranunculus repens x creeping thistle cirsium arvense x cuckoo flower cardamine pratensis x Curled dock Ruxex crispus X cut-leafed cranesbill geranium dissectum x cylcamen cyclamen sp. x daffodil narcissus sp. x dandelion taraxacum agg. x elder sambucus nigra elm ulmus sp. x European gorse Ulex europaeus x false oat grass Arrhenatherum elatius x fescue sp. -

Taxonomy, Origin and Importance of the Apiaceae Family

1 TAXONOMY, ORIGIN AND IMPORTANCE OF THE APIACEAE FAMILY JEAN-PIERRE REDURON* Mulhouse, France The Apiaceae (or Umbelliferae) is a plant family comprising at the present time 466 genera and about 3800 species (Plunkett et al., 2018). It is distributed nearly worldwide, but is most diverse in temperate climatic areas, such as Eurasia and North America. It is quite rare in tropical humid regions where it is limited to high mountains. Mediterranean and arid climatic conditions favour high species diversification. The Apiaceae are present in nearly all types of habi- tats, from sea-level to alpine zones: aquatic biotopes, grasslands, grazed pas- tures, forests including their clearings and margins, cliffs, screes, rocky hills, open sandy and gravelly soils, steppes, cultivated fields, fallows, road sides and waste grounds. The largest number of genera, 289, and the largest generic endemism, 177, is found in Asia. There are 126 genera in Europe, but only 17 are en- demic. Africa has about the same total with 121 genera, where North Africa encompasses the largest occurrence of 82 genera, 13 of which are endemic. North and Central America have a fairly high level of diversity with 80 genera and 44 endemics, where South America accommodates less generic diversity with 35 genera, 15 of which are endemic. Oceania is home to 27 genera and 18 endemics (Plunkett et al., 2018). The Apiaceae family appears to have originated in Australasia (region including Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, New Guinea, New Caledonia and several island groups), with this origin dated to the Late Cretaceous/ early Eocene, c.87 Ma (Nicolas and Plunkett, 2014). -

Ethnobotanical Review of Wild Edible Plants in Spain

Blackwell Publishing LtdOxford, UKBOJBotanical Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4074The Linnean Society of London, 2006? 2006 View metadata, citation and similar papers1521 at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 2771 Original Article provided by Digital.CSIC EDIBLE WILD PLANTS IN SPAIN J. TARDÍO ET AL Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2006, 152, 27–71. With 2 figures Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain JAVIER TARDÍO1*, MANUEL PARDO-DE-SANTAYANA2† and RAMÓN MORALES2 1Instituto Madrileño de Investigación y Desarrollo Rural, Agrario y Alimentario (IMIDRA), Finca El Encín, Apdo. 127, E-28800 Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain 2Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC, Plaza de Murillo 2, E-28014 Madrid, Spain Received October 2005; accepted for publication March 2006 This paper compiles and evaluates the ethnobotanical data currently available on wild plants traditionally used for human consumption in Spain. Forty-six ethnobotanical and ethnographical sources from Spain were reviewed, together with some original unpublished field data from several Spanish provinces. A total of 419 plant species belonging to 67 families was recorded. A list of species, plant parts used, localization and method of consumption, and harvesting time is presented. Of the seven different food categories considered, green vegetables were the largest group, followed by plants used to prepare beverages, wild fruits, and plants used for seasoning, sweets, preservatives, and other uses. Important species according to the number of reports include: Foeniculum vulgare, Rorippa nasturtium-aquaticum, Origanum vulgare, Rubus ulmifolius, Silene vulgaris, Asparagus acutifolius, and Scolymus hispanicus. We studied data on the botanical families to which the plants in the different categories belonged, over- lapping between groups and distribution of uses of the different species. -

The Cevennes

France - The Cevennes Naturetrek Tour Report 16 - 23 May 2018 Short-toed Snake Eagle Botanising on the Causse Mejean View down into Tarn Gorge near Saint Enimie Little Blue butterflies at edge of River Tarn Report and images by Jenny & John Willsher Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report France - The Cevennes Tour participants: Jenny & John Willsher (Tour leaders) and 14 Naturetrek clients Summary In the southernmost part of the Massif Central are the rugged and dramatic landscapes of the Cevennes and Causses surrounding the attractive town of Florac. This area, with its diversity of landscapes, meant a wildlife rich week in this beautiful and peaceful part of France, enjoying masses of colourful and intriguing plants, many species of butterflies and some great birds. As we ascended the Corniche de Cevennes on our arrival day the roadsides were dotted with orchids and Meadow Saxifrage, and a meadow of Poet's Narcissi gave us a flavour of the week ahead. The colours of the forests, meadows and rocky roadside banks were wonderful. The weather was better than the early forecast had suggested, indeed there had been snow on the Causse Mejean only a few days earlier, and even on the notorious Mont Aigoul we had sunshine but it was not quite clear enough for the promised views to the Camargue, the Alps and the Pyrenees. Orchid species were prolific, with drifts of the red and yellow Elder-flowered Orchid and banks of Monkey, Lady and Military Orchids in profusion, and the air was rich with the scent of various broom species. -

SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE

National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Contents White / Cream ................................ 2 Grasses ...................................... 130 Yellow ..........................................33 Rushes ....................................... 138 Red .............................................63 Sedges ....................................... 140 Pink ............................................66 Shrubs / Trees .............................. 148 Blue / Purple .................................83 Wood-rushes ................................ 154 Green / Brown ............................. 106 Indexes Aquatics ..................................... 118 Common name ............................. 155 Clubmosses ................................. 124 Scientific name ............................. 160 Ferns / Horsetails .......................... 125 Appendix .................................... 165 Key Traffic light system WF symbol R A G Species with the symbol G are For those recording at the generally easier to identify; Wildflower Level only. species with the symbol A may be harder to identify and additional information is provided, particularly on illustrations, to support you. Those with the symbol R may be confused with other species. In this instance distinguishing features are provided. Introduction This guide has been produced to help you identify the plants we would like you to record for the National Plant Monitoring Scheme. There is an index at -

Title: Occurrence of Temporarily-Introduced Alien Plant Species (Ephemerophytes) in Poland - Scale and Assessment of the Phenomenon

Title: Occurrence of temporarily-introduced alien plant species (ephemerophytes) in Poland - scale and assessment of the phenomenon Author: Alina Urbisz Citation style: Urbisz Alina. (2011). Occurrence of temporarily-introduced alien plant species (ephemerophytes) in Poland - scale and assessment of the phenomenon. Katowice : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. Cena 26 z³ (+ VAT) ISSN 0208-6336 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Œl¹skiego Katowice 2011 ISBN 978-83-226-2053-3 Occurrence of temporarily-introduced alien plant species (ephemerophytes) in Poland – scale and assessment of the phenomenon 1 NR 2897 2 Alina Urbisz Occurrence of temporarily-introduced alien plant species (ephemerophytes) in Poland – scale and assessment of the phenomenon Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Katowice 2011 3 Redaktor serii: Biologia Iwona Szarejko Recenzent Adam Zając Publikacja będzie dostępna — po wyczerpaniu nakładu — w wersji internetowej: Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa 4 www.sbc.org.pl Contents Acknowledgments .................. 7 Introduction .................... 9 1. Aim of the study .................. 11 2. Definition of the term “ephemerophyte” and criteria for classifying a species into this group of plants ............ 13 3. Position of ephemerophytes in the classification of synanthropic plants 15 4. Species excluded from the present study .......... 19 5. Material and methods ................ 25 5.1. The boundaries of the research area ........... 25 5.2. List of species ................. 25 5.3. Sources of data ................. 26 5.3.1. Literature ................. 26 5.3.2. Herbarium materials .............. 27 5.3.3. Unpublished data ............... 27 5.4. Collection of records and list of localities ......... 27 5.5. Selected of information on species ........... 28 6. Results ..................... 31 6.1. Systematic classification ............... 31 6.2. Number of localities ................ 33 6.3. Dynamics of occurrence .............. -

Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants Volume 11, Modifi Ed Stems, Roots, Bulbs Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants

T. K. Lim Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants Volume 11, Modifi ed Stems, Roots, Bulbs Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants T. K. Lim Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants Volume 11, Modifi ed Stems, Roots, Bulbs ISBN 978-3-319-26061-7 ISBN 978-3-319-26062-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-26062-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011932982 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Acknowledgements Special thanks for the use of digital images are accorded to Cecilia Lafosse (CIP) and Ezeta Fernando (ex CIP), International Potato Centre (CIP) for oca ( Oxalis tuberosa ). -

Know Your Umbellifers! – THIS COULD 'SAVE YOUR SKIN' AND

Know your umbellifers! – THIS COULD ‘SAVE YOUR SKIN’ AND EVEN YOUR LIFE! Since compiling the wildflower challenge, I’ve been asked what the difference is between cow parsley and hemlock/poison hemlock, as the plants look similar. However, one can be picked safely, some parts foraged and eaten without a problem and the other causes awful skin damage and blistering, if handled, and is very poisonous if ingested. (You may remember from history that the Greek philosopher, Socrates (in 399 BC), was executed by consuming a hemlock derived drink. Hemlock was used in ancient Greece to poison condemned prisoners. In addition, there are other ‘look-alikes’, of which some are ‘sweet and innocent’ but the most super- sized and highly toxic one of them all is giant hogweed. It is currently in the news, as with the recent warm weather it is growing fast and flowering early and, as it tends to grow where people are now enjoying more outside freedom after lock down children, in particular, are being attracted to its unique appearance and suffering horrifying, life-changing consequences by just touching it (see photographs right). (More on how to spot giant hogweed and other ‘look-a-likes’ later, after comparing our first two.) Here’s a bit of botany (info about plants) from which you will see that cow parsley and poison hemlock are ‘related’, have many similar characteristics and it’s not surprising they are often confused! An umbel is an ‘inflorescence’ – now don’t be put off! (Inflorescence just means a group/cluster of flowers on a main stem or a branched stem.) So, an umbel has a number of flowers on short flower stalks (pedicels) which spread from a common point, like the ‘ribs’ of an umbrella. -

Occurrence of Temporarily-Introduced Alien Plant Species (Ephemerophytes) in Poland – Scale and Assessment of the Phenomenon

Cena 26 z³ (+ VAT) ISSN 0208-6336 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Œl¹skiego Katowice 2011 ISBN 978-83-226-2053-3 Occurrence of temporarily-introduced alien plant species (ephemerophytes) in Poland – scale and assessment of the phenomenon 1 NR 2897 2 Alina Urbisz Occurrence of temporarily-introduced alien plant species (ephemerophytes) in Poland – scale and assessment of the phenomenon Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Katowice 2011 3 Redaktor serii: Biologia Iwona Szarejko Recenzent Adam Zając Publikacja będzie dostępna — po wyczerpaniu nakładu — w wersji internetowej: Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa 4 www.sbc.org.pl Contents Acknowledgments .................. 7 Introduction .................... 9 1. Aim of the study .................. 11 2. Definition of the term “ephemerophyte” and criteria for classifying a species into this group of plants ............ 13 3. Position of ephemerophytes in the classification of synanthropic plants 15 4. Species excluded from the present study .......... 19 5. Material and methods ................ 25 5.1. The boundaries of the research area ........... 25 5.2. List of species ................. 25 5.3. Sources of data ................. 26 5.3.1. Literature ................. 26 5.3.2. Herbarium materials .............. 27 5.3.3. Unpublished data ............... 27 5.4. Collection of records and list of localities ......... 27 5.5. Selected of information on species ........... 28 6. Results ..................... 31 6.1. Systematic classification ............... 31 6.2. Number of localities ................ 33 6.3. Dynamics of occurrence ............... 34 6.4. Introduction pathways ............... 45 6.5. Origin .................... 52 6.6. The habitats occupied by ephemerophytes ......... 54 7. Discussion .................... 55 7.1. Reasons for distinguishing the group of ephemerophytes ..... 55 7.2. Dynamics of the occurrence of ephemerophytes and introduction path- ways .................... 57 7.3. -

Edible Nuts. Non-Wood Forest Products

iii <J)z o '"o ~ NON-WOODNO\ -WOOD FORESTFOREST PRODUCTSPRODUCTS o 55 Edible nuts Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations NON-WOOD0 \ -WOOD FOREST FOREST PRODUCTS PRODUCTS 55 EdibleEdible nuts by G.E. Wickens FOOD AND AGRICULTUREAGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITEDUNITED NATIONSNATIONS Rome,Rome, 19951995 The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflectreflect opinionsopinions onon thethe partpart ofof FAO.FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do notnot implyimplythe the expressionexpression ofof any anyopinion opinion whatsoever whatsoever onon thethe part of thethe FoodFood andand AgricultureAgriculture OrganizationOrganization of thethe UnitedUnited Nations concerning the legal status of any country,country, territory,territory, citycity oror area or ofof itsits authorities, authorities, orconcerningor concerning the the delimitation delimitation ofof its its frontiers frontiers or boundaries.boundaries. M-37 ISBNISBN 92-5-103748-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,reproduced , stored in a retrieval systemsystem,, or transmitted inin any formform oror byby anyany means, means ,electronic, electronic, mechanicalmechanical,, photocopying oror otherwiseotherwise,, without the prior permissionpermission ofof thethe copyright owner. Applications forfor such permission,permission, withwith a statementstatement of thethe purpose and extent of the reproduction,reproduction, should be addressed to the