The Wild Plants of Scotia Illustrata (1684)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd Position in Ecology and Evolutionary Botany

PhD in Biology Institut de Biologie LaborAtoire de génétique PhD position in ecology and evolutionary évolutive botany Available from February 1, 2020 INFORMATION A four-year PhD position combining ecology and evolutionary botany is available in the Laboratory of evolutionary genetics, Institute of Biology, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland. The thesis is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) within the framework of a Sinergia project. It is directed by Prof. Jason Grant (UniNe) and co-supervised by Dr. Pierre-Emmanuel Du Pasquier (UniNe) and Dr. Beryl Laitung (Université de Bourgogne, UMR Agroécologie, DiJon, France). BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES Anthropic pressure may lead to the rapid and sometimes irreversible decline of botanical diversity, or on the contrary, favors the expansion of certain non-native species. In Europe, since the mid-20th century, the intensification and modernization of agricultural practices (mechanization with deep ploughing, use of herbicides, seed sorting, densification of monocultures and systematic use of certified seeds) has had an unprecedented impact on archaeophyte messicole species (crop-related species that were introduced mainly from the Middle East before the year 1500). As messicole species are generally therophytes (annual plants that spend the difficult season in the form of seeds), modernization quickly destroys seed stocks in the soil and contributes to the decline of these populations that were common until the mid-20th century. Although messicolous species are part of the floristic richness of the different countries where they are now native, they seem to have been introduced in the past by man in the form of seed since the domestication of crops from the Neolithic period (11000 to 9000 years ago). -

Yellow Rattle Rhinanthus Minor

Yellow Rattle Rhinanthus minor Yellow rattle is part of the figwort family (Scrophulariaceae) and is an annual plant associated with species-rich meadows. It can grow up to 50 cm tall and the stem can have black spots. Pairs of triangular serrated leaves are arranged in opposite pairs up the stem and the stem may have several branches. Flowers are arranged in leafy spikes at the top of the stem and the green calyx tube at the bottom of each flower is flattened, slightly inflated and bladder-like. The yellow flowers are also flattened and bilaterally symmetrical. The upper lip has two short 1 mm violet teeth and the lower lip has three lobes. The flattened seeds rattle inside the calyx when ripe. Lifecycle Yellow rattle is an annual plant germinating early in the year, usually February – April, flowering in May – August and setting seed from July – September before the plant dies. The seeds are large and may not survive long in the soil seed bank. Seed germination trials have found that viability quickly reduces within six months, and spring sown seed has a much lower germination rate. Yellow rattle seed often requires a period of cold, termed vernalisation, to trigger germination. It is a hemi-parasite on grasses and legumes. This means that it is partially parasitic, gaining energy through the roots of plants and also using photosynthesis. This ability of yellow rattle makes it extremely useful in the restoration of wildflower meadows as it reduces vegetation cover enabling perennial wildflowers to grow. However, some grasses, such as fescues, are resistant to parasitism by yellow rattle and in high nutrient soils, Yellow rattle distribution across Britain and Ireland grasses such as perennial rye-grass, may grow The data used to create these maps has been provided under very quickly shading out yellow rattle plants licence from the Botanical Society which are not tolerant of shady conditions. -

Coumarins and Iridoids from Crucianella Graeca, Cruciata Glabra, Cruciata Laevipes and Cruciata Pedemontana (Rubiaceae) Maya Iv

Coumarins and Iridoids from Crucianella graeca, Cruciata glabra, Cruciata laevipes and Cruciata pedemontana (Rubiaceae) Maya Iv. Mitova3, Mincho E. Anchevb, Stefan G. Panev3, Nedjalka V. Handjieva3 and Simeon S. Popov3 a Institute of Organic Chemistry with Centre of Phytochemistry, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia 1113, Bulgaria h Institute of Botany, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia 1113, Bulgaria Z. Naturforsch. 51c, 631-634 (1996); received May 23/July8 , 1996 Rubiaceae, Crucianella, Cruciata, Coumarins, Iridoids The coumarin and iridoid composition of Crucianella graeca, Cruciata glabra, Cruciata laevipes and Cruciata pedemontana has been studied. Daphnin and daphnetin glucoside do minated in C. glabra along with low concentrations of daphnetin, deacetylasperulosidic acid and scandoside. In C. laevipes and C. pedemontana were found the same coumarin glucosides along with six iridoid glucosides. In Crucianella graeca were found ten iridoid glucosides. Introduction Thirteen pure compounds (Fig. 1) were isolated and identified by 'H and 13C NMR spectra (Ta Crucianella L. and Cruciata Mill. (Rubiaceae) ble I) and comparisons with authentic samples as are represented each by three species in the Bul the coumarins, daphnin (1), daphnetin glucoside garian flora (Ancev, 1976, 1979). They are mor (2) and daphnetin (3) (Jevers et al., 1978) and the phologically well differentiated and all except iridoids, deacetylasperulosidic acid (4), scandoside Cruciata glabra (L.) Ehrend., do not suggest seri (5), asperuloside (6), asperulosidic acid (7), methyl ous taxonomic problems. The coumarins, scopo- ester of deacetylasperulosidic acid (8), daphyllo letin, umbelliferone and cruciatin and the iridoid side (9), geniposidic acid (10), 10-hydroxyloganin glucosides monotropein, asperuloside and au- (11), deacetylasperuloside (12) and iridoid V3 (13) cubin, were found in some Cruciata species (Bo (Boros and Stermitz, 1990; El-Naggar & Beal, risov, 1967, 1974; Borisov and Borisyuk, 1965; Bo 1980). -

Apiaceae) - Beds, Old Cambs, Hunts, Northants and Peterborough

CHECKLIST OF UMBELLIFERS (APIACEAE) - BEDS, OLD CAMBS, HUNTS, NORTHANTS AND PETERBOROUGH Scientific name Common Name Beds old Cambs Hunts Northants and P'boro Aegopodium podagraria Ground-elder common common common common Aethusa cynapium Fool's Parsley common common common common Ammi majus Bullwort very rare rare very rare very rare Ammi visnaga Toothpick-plant very rare very rare Anethum graveolens Dill very rare rare very rare Angelica archangelica Garden Angelica very rare very rare Angelica sylvestris Wild Angelica common frequent frequent common Anthriscus caucalis Bur Chervil occasional frequent occasional occasional Anthriscus cerefolium Garden Chervil extinct extinct extinct very rare Anthriscus sylvestris Cow Parsley common common common common Apium graveolens Wild Celery rare occasional very rare native ssp. Apium inundatum Lesser Marshwort very rare or extinct very rare extinct very rare Apium nodiflorum Fool's Water-cress common common common common Astrantia major Astrantia extinct very rare Berula erecta Lesser Water-parsnip occasional frequent occasional occasional x Beruladium procurrens Fool's Water-cress x Lesser very rare Water-parsnip Bunium bulbocastanum Great Pignut occasional very rare Bupleurum rotundifolium Thorow-wax extinct extinct extinct extinct Bupleurum subovatum False Thorow-wax very rare very rare very rare Bupleurum tenuissimum Slender Hare's-ear very rare extinct very rare or extinct Carum carvi Caraway very rare very rare very rare extinct Chaerophyllum temulum Rough Chervil common common common common Cicuta virosa Cowbane extinct extinct Conium maculatum Hemlock common common common common Conopodium majus Pignut frequent occasional occasional frequent Coriandrum sativum Coriander rare occasional very rare very rare Daucus carota Wild Carrot common common common common Eryngium campestre Field Eryngo very rare, prob. -

Design a Database of Italian Vascular Alimurgic Flora (Alimurgita): Preliminary Results

plants Article Design a Database of Italian Vascular Alimurgic Flora (AlimurgITA): Preliminary Results Bruno Paura 1,*, Piera Di Marzio 2 , Giovanni Salerno 3, Elisabetta Brugiapaglia 1 and Annarita Bufano 1 1 Department of Agricultural, Environmental and Food Sciences University of Molise, 86100 Campobasso, Italy; [email protected] (E.B.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Bioscience and Territory, University of Molise, 86090 Pesche, Italy; [email protected] 3 Graduate Department of Environmental Biology, University “La Sapienza”, 00100 Roma, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Despite the large number of data published in Italy on WEPs, there is no database providing a complete knowledge framework. Hence the need to design a database of the Italian alimurgic flora: AlimurgITA. Only strictly alimurgic taxa were chosen, excluding casual alien and cultivated ones. The collected data come from an archive of 358 texts (books and scientific articles) from 1918 to date, chosen with appropriate criteria. For each taxon, the part of the plant used, the method of use, the chorotype, the biological form and the regional distribution in Italy were considered. The 1103 taxa of edible flora already entered in the database equal 13.09% of Italian flora. The most widespread family is that of the Asteraceae (20.22%); the most widely used taxa are Cichorium intybus and Borago officinalis. The not homogeneous regional distribution of WEPs (maximum in the south and minimum in the north) has been interpreted. Texts published reached its peak during the 2001–2010 decade. A database for Italian WEPs is important to have a synthesis and to represent the richness and Citation: Paura, B.; Di Marzio, P.; complexity of this knowledge, also in light of its potential for cultural enhancement, as well as its Salerno, G.; Brugiapaglia, E.; Bufano, applications for the agri-food system. -

Analysis of Paralogs in Target Enrichment Data Pinpoints Multiple Ancient Polyploidy Events

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261925; this version posted August 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 1 Analysis of paralogs in target enrichment data pinpoints multiple ancient polyploidy events 2 in Alchemilla s.l. (Rosaceae). 3 4 Diego F. Morales-Briones1.2,*, Berit Gehrke3, Chien-Hsun Huang4, Aaron Liston5, Hong Ma6, 5 Hannah E. Marx7, David C. Tank2, Ya Yang1 6 7 1Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, 1445 Gortner 8 Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA 9 2Department of Biological Sciences and Institute for Bioinformatics and Evolutionary Studies, 10 University of Idaho, 875 Perimeter Drive MS 3051, Moscow, ID 83844, USA 11 3University Gardens, University Museum, University of Bergen, Mildeveien 240, 5259 12 Hjellestad, Norway 13 4State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering and Collaborative Innovation Center of Genetics 14 and Development, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecological 15 Engineering, Institute of Plant Biology, Center of Evolutionary Biology, School of Life Sciences, 16 Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China 17 5Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, 2082 Cordley Hall, 18 Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 19 6Department of Biology, the Huck Institute of the Life Sciences, the Pennsylvania State 20 University, 510D Mueller Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802 USA 21 7Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 22 48109-1048, USA 23 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.261925; this version posted August 23, 2020. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

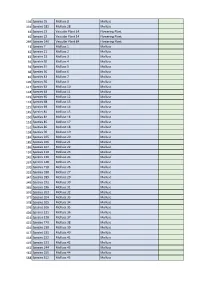

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Notes on Identification Works and Difficult and Under-Recorded Taxa

Notes on identification works and difficult and under-recorded taxa P.A. Stroh, D.A. Pearman, F.J. Rumsey & K.J. Walker Contents Introduction 2 Identification works 3 Recording species, subspecies and hybrids for Atlas 2020 6 Notes on individual taxa 7 List of taxa 7 Widespread but under-recorded hybrids 31 Summary of recent name changes 33 Definition of Aggregates 39 1 Introduction The first edition of this guide (Preston, 1997) was based around the then newly published second edition of Stace (1997). Since then, a third edition (Stace, 2010) has been issued containing numerous taxonomic and nomenclatural changes as well as additions and exclusions to taxa listed in the second edition. Consequently, although the objective of this revised guide hast altered and much of the original text has been retained with only minor amendments, many new taxa have been included and there have been substantial alterations to the references listed. We are grateful to A.O. Chater and C.D. Preston for their comments on an earlier draft of these notes, and to the Biological Records Centre at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology for organising and funding the printing of this booklet. PAS, DAP, FJR, KJW June 2015 Suggested citation: Stroh, P.A., Pearman, D.P., Rumsey, F.J & Walker, K.J. 2015. Notes on identification works and some difficult and under-recorded taxa. Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Bristol. Front cover: Euphrasia pseudokerneri © F.J. Rumsey. 2 Identification works The standard flora for the Atlas 2020 project is edition 3 of C.A. Stace's New Flora of the British Isles (Cambridge University Press, 2010), from now on simply referred to in this guide as Stae; all recorders are urged to obtain a copy of this, although we suspect that many will already have a well-thumbed volume. -

Alien Plants in Temperate Weed Communities: Prehistoric and Recent Invaders Occupy Different Habitats

Ecology, 86(3), 2005, pp. 772±785 q 2005 by the Ecological Society of America ALIEN PLANTS IN TEMPERATE WEED COMMUNITIES: PREHISTORIC AND RECENT INVADERS OCCUPY DIFFERENT HABITATS PETR PYSÏ EK,1,2,5 VOJTEÏ CH JAROSÏÂõK,1,2 MILAN CHYTRY ,3 ZDENEÏ K KROPA CÏ ,4 LUBOMÂõR TICHY ,3 AND JAN WILD1 1Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-252 43 PruÊhonice, Czech Republic 2Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, VinicÏna 7, CZ-128 01 Praha 2, Czech Republic 3Department of Botany, Masaryk University, KotlaÂrÏska 2, CZ-611 37 Brno, Czech Republic 4SlavõÂkova 16, CZ-130 00 Praha 3, Czech Republic Abstract. Variables determining the number of native and alien plants on arable land in Central Europe are identi®ed. Species richness of 698 samples of weed ¯oras recorded in the Czech Republic in plots of a standard size of 100 m2 in 1955±2000 was studied in relation to altitudinally based ¯oristic region, soil type, type of cultivated crop, climatic variables, altitude, year of the record, crop cover and height, and human population density in the region. Vascular plant species were classi®ed into native and alien, the latter divided in archaeophytes, introduced before AD 1500, and neophytes, introduced after this date. The use of minimal adequate models in the analysis of covariance allowed determination of the net effects of mutually correlated environmental variables. Models for particular species groups explained 33±48% of variation in species numbers and 27±51% in propor- tions; however, explanatory variables affected native species, archaeophytes, and neophytes differently. -

FLORA from FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE of MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2

ISSN: 2601 – 6141, ISSN-L: 2601 – 6141 Acta Biologica Marisiensis 2018, 1(1): 60-70 ORIGINAL PAPER FLORA FROM FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE OF MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2 1Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tîrgu Mureş, Romania 2Mureş County Museum, Department of Natural Sciences, Tîrgu Mureş, Romania *Correspondence: Silvia OROIAN [email protected] Received: 2 July 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 15 July 2018 Abstract The aim of this study was to identify a potential source of medicinal plant from Transylvanian Plain. Also, the paper provides information about the hayfields floral richness, a great scientific value for Romania and Europe. The study of the flora was carried out in several stages: 2005-2008, 2013, 2017-2018. In the studied area, 397 taxa were identified, distributed in 82 families with therapeutic potential, represented by 164 medical taxa, 37 of them being in the European Pharmacopoeia 8.5. The study reveals that most plants contain: volatile oils (13.41%), tannins (12.19%), flavonoids (9.75%), mucilages (8.53%) etc. This plants can be used in the treatment of various human disorders: disorders of the digestive system, respiratory system, skin disorders, muscular and skeletal systems, genitourinary system, in gynaecological disorders, cardiovascular, and central nervous sistem disorders. In the study plants protected by law at European and national level were identified: Echium maculatum, Cephalaria radiata, Crambe tataria, Narcissus poeticus ssp. radiiflorus, Salvia nutans, Iris aphylla, Orchis morio, Orchis tridentata, Adonis vernalis, Dictamnus albus, Hammarbya paludosa etc. Keywords: Fărăgău, medicinal plants, human disease, Mureş County 1. -

Amaranthaceae Pollens: Review of an Emerging Allergy in the Mediterranean Area M Villalba,1 R Barderas,1 S Mas,1 C Colás,2 E Batanero,1 R Rodríguez1

REVIEWS Amaranthaceae Pollens: Review of an Emerging Allergy in the Mediterranean Area M Villalba,1 R Barderas,1 S Mas,1 C Colás,2 E Batanero,1 R Rodríguez1 1Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular I, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain 2Hospital Clínico Universitario "Lozano Blesa", Zaragoza, Spain Abstract The Amaranthaceae family is composed of about 180 genera and 2500 species. These common weeds have become increasingly relevant as triggers of allergy in the last few years, as they are able to rapidly colonize salty and arid soils in extensive desert areas. The genera Chenopodium, Salsola, and Amaranthus are the major sources of pollinosis from the Amaranthaceae family in southern Europe, western United States, and semidesert areas of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iran. In Spain, Salsola kali is one of the most relevant causes of pollinosis, together with olive and grasses. To date, 9 Amaranthaceae pollen allergens from Chenopodium album, Salsola kali, and Amaranthus retroflexus have been described and are listed in the International Union of Immunological Societies allergen nomenclature database. The major allergens of Amaranthaceae pollen belong to the pectin methylesterase, Ole e 1–like, and profilin panallergen families, whereas the minor allergens belong to the cobalamin- independent methionine synthase and polcalcin panallergen families. These relevant allergens have been characterized physicochemically, and immunologically at different levels. Recombinant forms, allergenic fusion recombinant proteins, and hypoallergenic derivatives of these allergens have been expressed in bacteria and yeast and compared with their natural proteins from pollen. In this review, we provide an extensive overview of Amaranthaceae pollen allergens, focusing on their physicochemical, and immunological properties and on their clinical significance in allergic patients. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database.