The Spectator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Alan Parker Donates Working Archives to Bfi

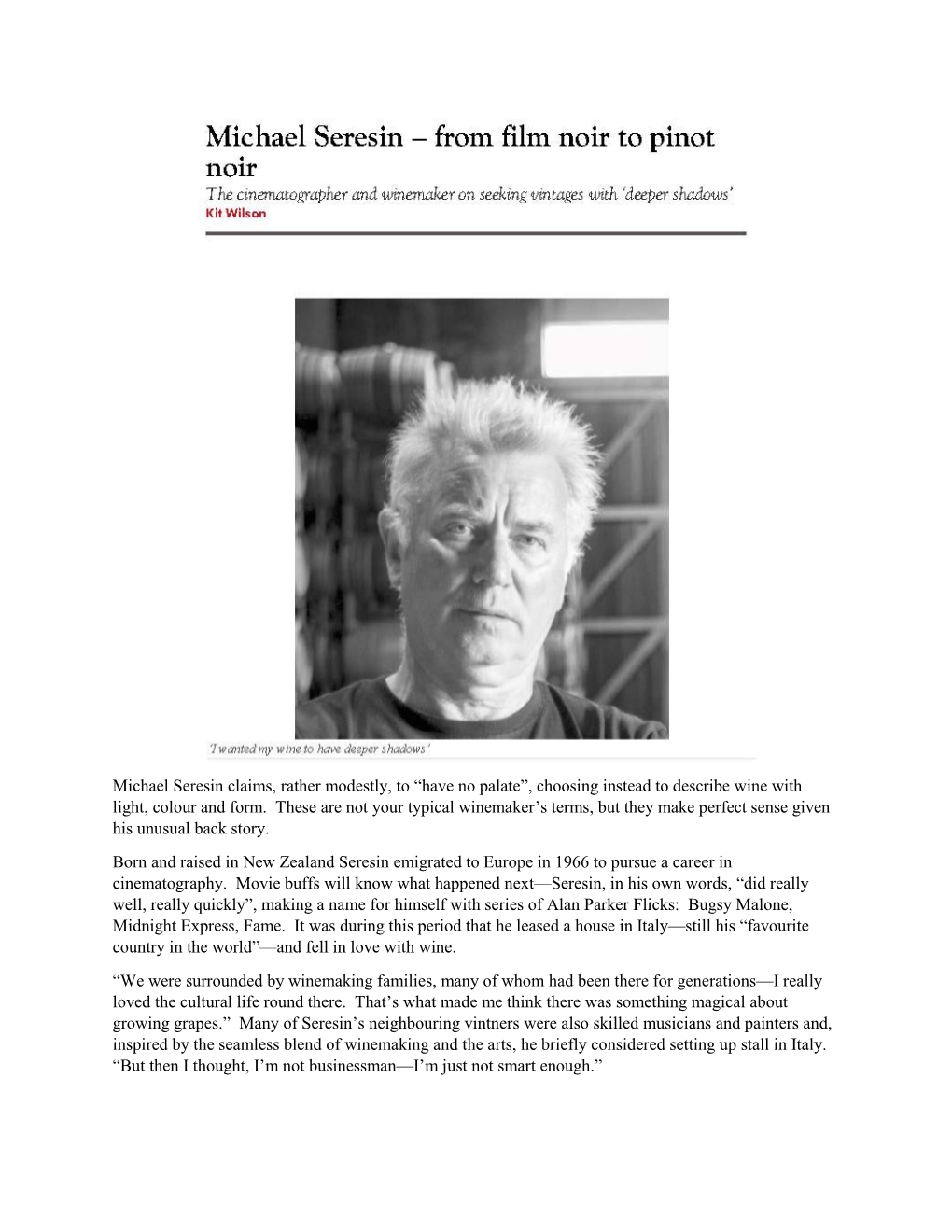

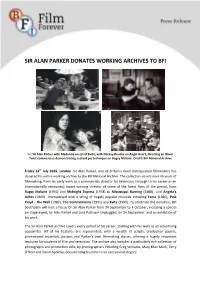

SIR ALAN PARKER DONATES WORKING ARCHIVES TO BFI l-r: Sir Alan Parker with Madonna on set of Evita; with Mickey Rourke on Angel Heart; directing an Oliver Twist commercial; demonstrating custard pie technique on Bugsy Malone. Credit: BFI National Archive Friday 24th July 2015, London. Sir Alan Parker, one of Britain’s most distinguished filmmakers has donated his entire working archive to the BFI National Archive. The collection covers over 45 years of filmmaking, from his early work as a commercials director for television, through to his career as an internationally renowned, award-winning director of some of the finest films of the period, from Bugsy Malone (1976) and Midnight Express (1978) to Mississippi Burning (1988) and Angela’s Ashes (1999) interspersed with a string of hugely popular musicals including Fame (1980), Pink Floyd - The Wall (1982), The Commitments (1991) and Evita (1996). To celebrate the donation, BFI Southbank will host a Focus On Sir Alan Parker from 24 September to 4 October, including a special on stage event, Sir Alan Parker and Lord Puttnam Unplugged, on 24 September, and an exhibition of his work. The Sir Alan Parker archive covers every period of his career, starting with his work as an advertising copywriter. All of his features are represented, with a wealth of scripts, production papers, promotional materials, posters and Parker’s own filmmaking diaries, offering a hugely important resource for students of film and television. The archive also includes a particularly rich collection of photographs and production stills, by photographers including Greg Williams, Mary Ellen Mark, Terry O'Neill and David Appleby, documenting his films to an exceptional degree. -

War for the Planet of the Apes (2017)

WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES (2017) ● Released by July 14th, 2017 ● 2 hours 20 minutes ● $150,000,000 (estimated) budget ● Matt Reeves directed ● Chernin Entertainment, TSG Entertainment ● Rated PG-13 for sequences of sci-fi violence and action, thematic elements, and some disturbing images QUICK THOUGHTS: ● Demetri Panos: ● OPINION: WITH MATT REEVES FLOURISHED STORYTELLLING, QUALITY PERFORMANCES, GRAND SCALE NARRATIVE; WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES CAPS OFF A RARE TRILOGY FEAT WHERE THE MOVIES JUST GOT BETTER AS THEY WENT ALONG. REEVES NOT ONLY ABLE TO DIRECT BIG SCALE ACTION, HE COMPOSES SHOTS THAT NOT ONLY CAPTURE INTIMATE EXPRESSION BUT GRAND SCALE LANDSCAPE. SPEAKING OF EXPRESSION; MOTION CAPTURE TECHNOLOGY IS REACHING IF NOT AT ITS PEAK! I ARGUE THAT IT IS SO GOOD, IT SHOULD BE CONSIDERED A PROSTHETIC. TO TAKE THAT ONE STEP FURTHER, THE ACADEMY SHOULD NOW TAKE NOTE AND NOT BE HINDERED TO NOTICE PERFORMANCES UNDER MOTION CAPTURE. IT IS NOT UNLIKE NOMINATING JOHN HURT FROM ELEPHANT MAN OR ERIC STOLTZ FROM MASK. ANDY SERKIS PERFORMANCE HERE TRANSCENDS THE MASK. HE PLAYS CEASAR AS A LEADER WHO NOT ONLY GRAPPLES WITH THE RESPONSIBILITY OF HIS RACE BUT WITH RAMIFICATIONS OF HIS DECISIONS. HIS IS A GRIPPING PERFORMANCE, ONE OF THE BEST OF THE SUMMER. WOODY HARRELSON’S, THE COLONEL, PERFORMANCE TEETERS FROM GOING OVER THE TOP BUT HIS CHARACTER MIRRORS REAL IFE PERSONAS, WHILE ONE CAN UNDERSTAND THE COLONEL’S MOTIVIATION, HIS ACTIONS ARE NOT THOSE BOUND BY RATIONALITY AND THEREFORE SCARY. ALSO, PROPS TO AMIAH MILLER WHOSE RE-IMAGINED NOVA IS ENDEARING AND STRONG. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

TITLE New Teachers Packet. INSTITUTION Journalism Education Association

DOCUMENT RESUME A ED 451 550 CS 510 TITLE New Teachers Packet. INSTITUTION Journalism Education Association. PUB DATE 1998-04-00 NOTE 217p.; Prepared by the Journalism Education Curriculum/Development Committee, Jan Hensel, Chair. Contributors include: Candace Perkins Bowen, Michele Dunaway, Mary Lu Foreman, Connie Fulkerson, Pat Graff, Jan Hensel, RobMelton, Scoobie Ryan, and Valerie Thompson. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Guides; Newspapers; Photojournalism; Production Techniques; Professional Associations; *Scholastic Journalism; School Publications; Secondary Education; Student Publications; Worksheets; Yearbooks ABSTRACT This packet of information for new scholastic journalism teachers (or advisers) compiles information on professional associations in journalism education, offers curriculum guides and general help, and contains worksheets and handouts. Sections of the packet are:(1) Professional Help (Journalism Education Association Information, and Other Scholastic Press Associations);(2) Curriculum Guides (Beginning Journalism, Electronic Publishing, Newspaper Production, and Yearbook Production);(3) General Helps (General Tips, Sample Publications Guidelines, Sample Ad Contract, and Sample Style Book); and (4) Worksheets and Handouts (materials cover General Journalism, Middle/Junior High, Newspaper, Photography, and Yearbook). (RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Journalism Education Association ma- Teackers -

Live in HD Film Streams Supporters Film

Film Streams Programming Calendar The Ruth Sokolof Theater . April – June 2010 v3.4 The Times of Harvey Milk 1984 © New Yorker Films/Photofest Out in Film June 3 – July 1, 2010 Word Is Out 1977 Law of Desire 1987 The Wedding Banquet 1993 The Times of Harvey Milk 1984 Mala Noche 1985 Longtime Companion 1989 High Art 1998 Prodigal Sons First-Run Happy Together 1997 © Kino/Photofest When it was released in the late 1970s, the documentary WORD IS OUT: and Wong Kar Wai (HAPPY TOGETHER) to ground- STORIES OF SOME OF OUR LIVES created a shockwave by talking openly breaking dramas (LONGTIME COMPANION, HIGH about lesbian and gay identity in America—decades before Ang Lee’s BROKE- ART) to pivotal documentaries such as THE TIMES BACK MOUNTAIN and Gus Van Sant’s MILK brought similar narratives to OF HARVEY MILK (an inspiration for Dustin Lance mainstream multiplexes. Presented in conjunction with LGBT Pride Month Black’s 2008 Oscar-winning script for MILK), Kim- 2010, our Out in Film series features a variety of artistically innovative films berly Reed’s autobiographical new film PRODIGAL relating in different ways to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender experi- SONS, and a new UCLA restoration and Milestone ence—from early, important works by acclaimed directors Lee (THE WEDDING Films re-release of WORD IS OUT. BANQUET), Van Sant (MALA NOCHE), Pedro Almodóvar (LAW OF DESIRE), See reverse side of newsletter for full calendar of films and dates. Forever Young Family & Children’s Series Spring 2009 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 1968 James and A Town Called Panic First-Run the Giant Peach 1996 Mary Poppins 1964 Tahaan 2009 The Secret of Kells First-Run Bugsy Malone 1976 This spring our Forever Young series for all ages features half a century of great cinema, from Julie Andrews’ Oscar-winning screen debut as MARY POPPINS 46 years ago to the 2010 Academy Award Nominee for Best Animat- ed Feature THE SECRET OF KELLS. -

The Life of David Gale

Wettbewerb/IFB 2003 THE LIFE OF DAVID GALE DAS LEBEN DES DAVID GALE THE LIFE OF DAVID GALE Regie:Alan Parker USA 2002 Darsteller David Gale Kevin Spacey Länge 131 Min. Bitsey Bloom Kate Winslet Format 35 mm, Constance Harraway Laura Linney Cinemascope Zack Stemmons Gabriel Mann Farbe Dusty Wright Matt Craven Braxton Belyeu Leon Rippy Stabliste Berlin Rhona Mitra Buch Charles Randolph Nico Melissa McCarthy Kamera Michael Seresin Duke Grover Jim Beaver Kameraführung Mike Proudfoot Barbara Kreuster Cleo King Edward J.Adcock A.J.Roberts Constance Jones Kameraassistenz Bill Coe Joe Mullarkey Lee Ritchey Schnitt Gerry Hambling Jamie Gale Noah Truesdale Ton David McMillan Greer Chuck Cureau Musik Alex Parker Ross Sean Hennigan Jake Parker John Charles Sanders Production Design Geoffrey Kirkland Talkmaster Marco Perella Ausstattung Steve Arnold Gouverneur Hardin Michael Crabtree Jennifer Williams Sharon Gale Elizabeth Gast Requisite Don Miloyevich Laura Linney, Kevin Spacey Universitätspräsident Cliff Stephens Kostüm Renée Ehrlich Kalfus Maske Sarah Monzani Regieassistenz K.C.Hodenfield DAS LEBEN DES DAVID GALE Casting Juliet Taylor Dr.David Gale ist Professor an einer texanischen Universität – ein liebevoller Howard Feuer Vater und anerkannter Akademiker, der aus seinen Überzeugungen nie ein Herstellungsltg. David Wimbury Hehl gemacht hat. Dr. Gale ist ein engagierter Gegner der Todesstrafe und Produktionsltg. Alma Kuttruff als solcher wird er weithin respektiert. Doch dann geschieht das Unfassba- Produzenten Alan Parker Nicolas Cage re: Er wird angeklagt, Constance Harraway, eine junge Mitstreiterin, die ihn Executive Producers Moritz Borman in seinem Kampf um das Leben eines Verurteilten unterstützt hat, verge- Guy East waltigt und ermordet zu haben. Der Richter verurteilt ihn zum Tode. -

It's a Wonderful Life

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2017 It’s A Wonderful Life THE FLORIDA PROJECT | CINEMASTERS: THE COEN BROTHERS FILM STARS DON’T DIE IN LIVERPOOL | BFI: THRILLER THE KILLING OF A SACRED DEER | FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL GLASGOWFILM.ORG cinema for all GFT is a hub for cultural engagement, education and skills development. As a registered charity (SC005932) we depend on the generosity of our wonderful audiences to help support the work that we do. Every donation big or small can help make a real difference to the work of GFT. Go to: glasgowfilm.org/support-us and click DONATE Text ‘GFTD17’ + £1, £2, £3, £4, £5 or £10 to 70070 Give your donation at Box Office or Collection boxes in GFT. Your support will help us continue our rich variety of programmes and maintain Cinema for All. CINEMASTERS Take 2 FAMILY-FRIENDLY FILMS SOUND & VISION CONTENTS DIARY 6–10 The Killing of a Sacred Deer 15 78/52 21 Lawrence of Arabia - 70mm 19 The 2017 Jarman Award Touring The LEGO Ninjago Movie 12 44 Programme Lethal Weapon 43 Access Film Club: Patti Cake$ 45 The Lure 17 Access Film Club: Rare Exports 45 Manifesto: Live from Tate Modern 17 Babette’s Feast 39 Maze 23 The Ballad of Shirley Collins 22 Menashe 37 Battle of the Sexes 20 Miracle on 34th Street 13 Beach Rats 21 Mountain 37 The Big Heat 18 The Muppet Christmas Carol 12/14 The Bishop’s Wife 38 Murder on the Orient Express 39 Blade of the Immortal 38 Napping Princess 13 Blade Runner: The Final Cut 39 On the Road 22 Blade Runner 2049 39 Pyaasa 20 BRIDGIT / Adulteress 44 Predator 44 Brigsby Bear 24 The Prince of Nothingwood -

Crime Wave for Clara CRIME WAVE

Crime Wave For Clara CRIME WAVE The Filmgoers’ Guide to the Great Crime Movies HOWARD HUGHES Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published in 2006 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Howard Hughes, 2006 The right of Howard Hughes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The TCM logo and trademark and all related elements are trademarks of and © Turner Entertainment Networks International Limited. A Time Warner Company. All rights reserved. © and TM 2006 Turner Entertainment Networks International Limited. ISBN 10: 1 84511 219 9 EAN 13: 978 1 84511 219 6 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Typeset in Ehrhardt by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, -

Revue De Presse L'usure Du Temps D'alan Parker

REVUE DE PRESSE L’USURE DU TEMPS D’ALAN PARKER SORTIE CINÉMA 23 DÉCEMBRE 2015 « Un film intimiste et passionnant» CHARLIE HEBDO «Il faut absolument voir ce film méconnu d’Alan Parker. Parce qu’il sonne juste, parce qu’il est subtil et qu’il est d’une puissance émotionnelle rare. » PARISCOPE « À mi-chemin entre du Cassavetes et du Bergman, un film haut en couleurs. » TOUTE LA CULTURE « La plus grande réussite d’Alan Parker : un drame aussi poignant et délicat que tourmenté.» ÀVOIR-ÀLIRE « Au sein d’une photographie raffinée, voir jouer ensemble d’aussi grands comédiens que Diane Keaton et Albert Finney est un plaisir qui ne se refuse pas. » DVD CLASSIK « Intensifié par la photographie de Michael Seresin, ce drame psychologique, superbement rythmé, alterne sans cesse entre légèreté et gravité » CINECHRONICLE « Le choc en retour est 35 ans plus tard toujours aussi implacable. » DIGITAL CINE TOUTELACULTURE.COM - par Yaël Hirsch (le 22/12/2015) [Réédition] L’usure du temps, l’enfer du couple par Alan Parker Ce mercredi 23 décembre 2015 ressort sur les écrans français L’usure du temps (Shoot the Moon, 1981), le film le plus personnel d’Alan Parker (Fame, Pink Floyd, Evita). L’Association Française des Cinémas d’Art et d’Essai (AFCAE) et Splendor Films proposent de redécouvrir ce film puissant sur la fin d’un couple. Note de la rédaction : ★★★★★ Faith (Diane Keaton, sublime) et George (Albert Finney) vivent dans une maison avec leurs quatre enfants. Il est écrivain, elle est au foyer. Les enfants souffrent de leurs violentes disputes. -

GET LOW Directed by Aaron Schneider

2 GET LOW Directed by Aaron Schneider Screenplay by Chris Provenzano & C. Gaby Mitchell A Sony Pictures Classics Release Official Selection: 2009 Toronto International Film Festival 2010 Sundance Film Festival | 2010 South by Southwest Film Festival 2010 Tribeca Film Festival Screen Actors Guild Awards® Nominee, Robert Duvall - Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role Running Time: 100 Minutes | Rated PG-13 US Release Date: July 30th East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Rebecca Fisher Lindsay Macik [email protected] 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 917-653-6122 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 3 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax Synopsis reputation, but what he discovers is that behind Felix‘s surreal plan lies a very real and long-held secret that must get out. As Get Low is inspired by the true story of Felix ―Bush‖ the funeral approaches, the mystery– which involves the Breazeale, who attracted national attention and the largest widow Mattie Darrow (Sissy Spacek), the only person in town crowd to assemble up to that date when he threw himself a who ever got close to Felix, and the Illinois preacher Charlie living funeral party in 1938 in Roane County, Tennessee. Jackson (Bill Cobbs), who refuses to speak at his former friend‘s funeral – only deepens. But on the big day, Felix is in For years, townsfolk have been terrified of the backwoods no mood to listen to other people spinning made-up anecdotes recluse known as Felix Bush (Robert Duvall). -

Jan Apr 2010 Brochure.Pdf

Theatre l Music & Dance l Comedy l Film l Visual Arts January to April ‘10 ... the creative heart of the community Friends What’s On Welcome to 2010 at the Queen’s Hall Join our circle of Friends and We’ve got a great season lined up for you, with some of the best support the North East’s most 03 Queen’s Hall Friends * shows out on tour this Spring, including Trestle’s Moon Fool, Blackeyed vibrant Arts Centre. 04 January Theatre’s production of Alfie, Aly Bain & Phil Cunningham, and my favourite from the last Edinburgh Festival, 2Faced Dance with their 20% off tickets 06 February hip hop spectacular. And it’s not just great shows! Spreading across * 2 free tickets each season 09 March both galleries in February to banish the winter blues will be the * exclusive ticket exchange 13 April spectacular Contemporary African Art from the October Gallery in * London - a highlight of our annual exhibition programme. scheme Queen’s Hall Friends 14 Visual Arts special friends events As well as programming top professional artists we support a large 16 Taking Part * variety of community based activities. In this brochure you’ll find many Become a member of the Queen’s Hall 20 Season’s Diary shows from local amateurs, clubs and other groups. Our community Friends. Enjoy a range of great benefits for Exclusive Ticket Exchange Scheme 21 Seating Plan programme at the Queen’s Hall includes over 50 performances a year you and your friends. And save money! with an audience of more than 10,000, and a wide range of classes * Newsletter with advance details of each 20% off tickets for you and your guest 22 Box Office Info and workshops. -

DP a LE COMPLEXE.Indd 1 18/04/11 17:01:47 the Beaver

DP A LE COMPLEXE.indd 1 18/04/11 17:01:47 THE BEAVER SUMMIT INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY CONTACTS: DP A LE COMPLEXE.indd 2 18/04/11 17:01:47 Summit Entertainment and Participant Media Present in Association with Imagenation Abu Dhabi An Anonymous Content Production THE BEAVER French title : LE COMPLEXE DU CASTOR Starring MEL GIBSON JODIE FOSTER ANTON YELCHIN JENNIFER LAWRENCE, CHERRY JONES Written by KYLE KILLEN Directed by JODIE FOSTER Produced by STEVE GOLIN KEITH REDMON ANN RUARK Executive Producers JEFF SKOLL MOHAMMED MUBARAK AL MAZROUEI PAUL GREEN JONATHAN KING SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT 1630 Stewart St. - Ste. 120 - Santa Monica, CA 90404 Tel: +1 310 309 8400 - Fax: +1 310 828 4132 - Website: http://www.summit-ent.com SUMMIT INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY CONTACTS: JILL JONES: e: [email protected] - Tel: 310.309.8435 MELISSA MARTINEZ: e: [email protected] - Tel: 310.309.8436 ASMEETA NARAYAN: e: [email protected] - Tel: 310.309.8453 DP A LE COMPLEXE.indd 3 18/04/11 17:01:48 SYNOPSIS 3 DP A LE COMPLEXE.indd 4 18/04/11 17:01:48 SYNOPSIS Two-time Academy Award® winner Jodie Foster directs and co-stars with two- time Academy Award® winner Mel Gibson in The Beaver – an emotional story about a man on a journey to re-discover his family and re-start his life. Plagued by his own demons, Walter Black was once a successful toy executive and family man who now suffers from depression. No matter what he tries, Walter can’t seem to get himself back on track…until a beaver hand puppet enters his life.