Elephant Report Version 5-31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taken for a Ride

Taken for a ride The conditions for elephants used in tourism in Asia Author Dr Jan Schmidt-Burbach graduated in veterinary medicine in Germany and completed a PhD on diagnosing health issues in Asian elephants. He has worked as a wild animal veterinarian, project manager and wildlife researcher in Asia for more than 10 years. Dr Schmidt-Burbach has published several scientific papers on the exploitation of wild animals as part of the illegal wildlife trade and conducted a 2010 study on wildlife entertainment in Thailand. He speaks at many expert forums about the urgent need to address the suffering of wild animals in captivity. Acknowledgment This report has only been possible with the invaluable help of those who have participated in the fieldwork, given advice and feedback. Thanks particularly to: Dr Jennifer Ford, Lindsay Hartley-Backhouse, Soham Mukherjee, Manoj Gautam, Tim Gorski, Dananjaya Karunaratna, Delphine Ronfot, Julie Middelkoop and Dr Neil D’Cruze. World Animal Protection is grateful for the generous support from TUI Care Foundation and The Intrepid Foundation, which made this report possible. Preface Contents World Animal Protection has been moving the world to protect animals for more than 50 years. Currently working in over Executive summary 6 50 countries and on 6 continents, it is a truly global organisation. Protecting the world’s wildlife from exploitation and cruelty is central to its work. Introduction 8 The Wildlife - not entertainers campaign aims to end the suffering of hundreds of thousands of wild animals used and abused Background information 10 in the tourism entertainment industry. The strength of the campaign is in building a movement to protect wildlife. -

Thai Tourist Industry 'Driving' Elephant Smuggling 2 March 2013, by Amelie Bottollier-Depois

Thai tourist industry 'driving' elephant smuggling 2 March 2013, by Amelie Bottollier-Depois elephants for the amusement of tourists. Conservation activists accuse the industry of using illicitly-acquired animals to supplement its legal supply, with wild elephants caught in Myanmar and sold across the border into one of around 150 camps. "Even the so-called rescue charities are trying to buy elephants," said John Roberts of the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation. Domestic elephants in Thailand—where the pachyderm is a national symbol—have been employed en masse in the tourist trade since they An elephant performs for tourists during a show in found themselves unemployed in 1989 when Pattaya, on March 1, 2013. Smuggling the world's logging was banned. largest land animal across an international border sounds like a mammoth undertaking, but activists say Just 2,000 of the animals remain in the wild. that does not stop traffickers supplying Asian elephants to Thai tourist attractions. Prices have exploded with elephants now commanding between 500,000 and two million baht ($17,000 to $67,000) per baby, estimates suggest. Smuggling the world's largest land animal across an international border sounds like a mammoth undertaking, but activists say that does not stop traffickers supplying Asian elephants to Thai tourist attractions. Unlike their heavily-poached African cousins—whose plight is set to dominate Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) talks in Bangkok next week—Asian elephants do not often make the headlines. But the species is also under threat, as networks operate a rapacious trade in wild elephants to meet the demands of Thailand's tourist industry. -

“White Elephant” the King's Auspicious Animal

แนวทางการบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีนส าหรับโรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) สังกัดกรุงเทพมหานคร ประกอบด้วยองค์ประกอบหลักที่ส าคัญ 4 องค์ประกอบ ได้แก่ 1) เป้าหมายและ หลักการ 2) หลักสูตรและสื่อการสอน 3) เทคนิคและวิธีการสอน และ 4) การพัฒนาผู้สอนและผู้เรียน ค าส าคัญ: แนวทาง, การบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีน, โรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) Abstract This study aimed to develop a guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. The study was divided into 2 phases. Phase 1 was to investigate the present state and needs on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration from the perspectives of the involved personnel in Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Phase 2 was to create guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and to verify the accuracy and suitability of the guidelines by interviewing experts on teaching Chinese language and school management. A questionnaire, a semi-structured interview form, and an evaluation form were used as tools for collecting data. Percentage, mean, and Standard Deviation were employed for analyzing quantitative data. Modified Priority Needs Index (PNImodified) and content analysis were used for needs assessment and analyzing qualitative data, respectively. The results of this research found that the actual state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in all aspects was at a high level ( x =4.00) and the expected state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in the overall was at the highest level ( x =4.62). The difference between the actual state and the expected state were significant different at .01 level. -

Elephant Bibliography Elephant Editors

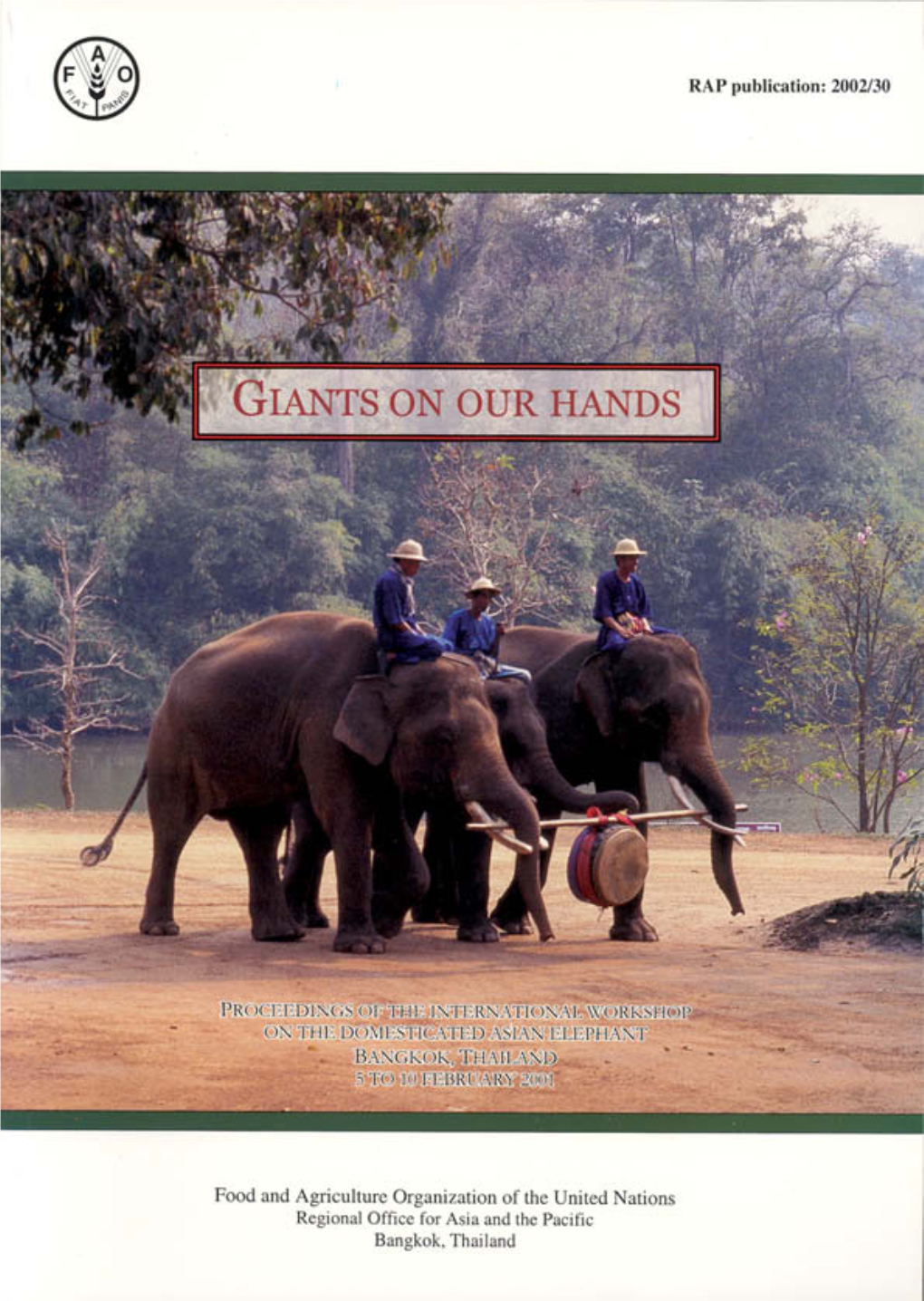

Elephant Volume 2 | Issue 3 Article 17 12-20-1987 Elephant Bibliography Elephant Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/elephant Recommended Citation Shoshani, J. (Ed.). (1987). Elephant Bibliography. Elephant, 2(3), 123-143. Doi: 10.22237/elephant/1521732144 This Elephant Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Elephant by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Fall 1987 ELEPHANT BIBLIOGRAPHY: 1980 - PRESENT 123 ELEPHANT BIBLIOGRAPHY With the publication of this issue we have on file references for the past 68 years, with a total of 2446 references. Because of the technical problems and lack of time, we are publishing only references for 1980-1987; the rest (1920-1987) will appear at a later date. The references listed below were retrieved from different sources: Recent Literature of Mammalogy (published by the American Society of Mammalogists), Computer Bibliographic Search Services (CCBS, the same used in previous issues), books in our office, EIG questionnaires, publications and other literature crossing the editors' desks. This Bibliography does not include references listed in the Bibliographies of previous issues of Elephant. A total of 217 new references has been added in this issue. Most of the references were compiled on a computer using a special program developed by Gary L. King; the efforts of the King family have been invaluable. The references retrieved from the computer search may have been slightly altered. These alterations may be in the author's own title, hyphenation and word segmentation or translation into English of foreign titles. -

The Surin Project

ELEPHANT NATURE FOUNDATION The Surin Project AN OVERVIEW OF THE CAPTIVE ELEPHANT SITUATION IN THAILAND (Taken from “Distribution and demography of Asian elephants in the Tourism industry in Northern Thailand. Naresuan University. 2009. Alexander Godfrey) ELEPHANT NATURE FOUNDATION 1. STATUS OF THE ASIAN ELEPHANT IN THAILAND The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) occurs in the wild in 13 countries ranging across South East Asia and South Asia. Used by humans for over 4,000 years, a significant number of individuals are found in captivity throughout the majority of range states. Thailand possesses an estimated 1000-1500 wild individuals, most of which occur in protected areas such as Khao Yai National Park and Huay Kha Keng Wildlife Sanctuary. However, contrary to most other countries, Thailand holds a higher number of captive individuals than wild ones, the former comprising approximately 60% of the total population. The wild and captive elephants in Thailand fall under different legislations. The wild population essentially comes under the 1992 Wildlife Protection Act granting it a certain level of protection from any form of anthropocentric use. The captive population however comes under the somewhat outdated 1939 Draught Animal Act, classifying it as working livestock, similar to cattle, buffalo and oxen. Internationally, the Asian Elephant is classified as “Endangered” on the IUCN Red List (1994) and is thus protected under the CITES Act, restricting and monitoring international trade. Habitat loss and fragmentation have been recognized as the most significant threats to wild elephants in Thailand. Although the overall percentage of forest cover has been increasing in Thailand in the last few years, much of this is mono- specific plantations such as eucalyptus and palm. -

Elephas Maximus) in Thailand

Student Research Project: 1st of September – 30th of November 2008 Genetic management of wild Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus) in Thailand Analysis of mitochondrial DNA from the d-loop region R.G.P.A. Rutten 0461954 Kasetsart University, Thailand Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Nakorn Pathom Supervisors: Dr. J.A. Lenstra Prof. W. Wajjwalku PhD student S. Dejchaisri Table of contents: Abstract:................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction:......................................................................................................................... 4 Materials and methods: ....................................................................................................... 9 Results: ................................................................................................................................ 14 Acknowledgements: ........................................................................................................... 26 References:.......................................................................................................................... 27 Attachments:....................................................................................................................... 30 Attachment I: DNA isolation and purification protocol: ................................................. 31 Attachment II: Comparison of the base pair positions in which the Fernando et al. (2003(a)), Fickel et al. (2007) haplotypes -

Analysis of the Khmer Walled Defensive System of Vimayapura (Phimai City, Thailand): Symbolism Or Military Effectiveness?

manusya 23 (2020) 253-285 brill.com/mnya Analysis of the Khmer Walled Defensive System of Vimayapura (Phimai City, Thailand): Symbolism or Military Effectiveness? Víctor Lluís Pérez Garcia1 (บิกตอร์ ยูอิส เปเรซ การ์เซีย) Ph.D. in Archaeology, history teacher of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Institut Tarragona, Tarragona, Spain [email protected] Abstract This article analyses the walled defensive system of the Khmer city centre of Vimaya- pura (modern Phimai, Thailand) to evaluate the theoretical level of military effectivity of both the walls and the moats against potential attackers, considering their technical characteristics and the enemy’s weapons. We also study the layout of the urban en- ceinte, the constructive material, the gateways as well as weakness and strengths of the stronghold and the symbolic, monumental and ornamental functions in the overall role of the walls. Based on comparisons with similar cases, as well as in situ observa- tions of the archaeological remains and a bibliographical research, our study reveals that the stonewalls were not designed primarily to resist military attacks. Instead, the army, the moat, and possibly the embankments and/or palisades would have been the first lines of defence of the city. Keywords fortifications – city walls – military architecture – Thailand – South-East Asia 1 Member of the “Seminary of Ancient Topography” archaeological research group at Universi- tat Rovira i Virgili of Tarragona (Catalonia). www.victorperez.webs.com. © Víctor Lluís Pérez Garcia, 2020 | doi:10.1163/26659077-02302006 -

Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants

BIOLOGY, MEDICINE, AND SURGERY OF ELEPHANTS BIOLOGY, MEDICINE, AND SURGERY OF ELEPHANTS Murray E. Fowler Susan K. Mikota Murray E. Fowler is the editor and author of the bestseller Zoo Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or and Wild Animal Medicine, Fifth Edition (Saunders). He has written the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by Medicine and Surgery of South American Camelids; Restraint and Blackwell Publishing, provided that the base fee is paid directly to Handling of Wild and Domestic Animals and Biology; and Medicine the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, and Surgery of South American Wild Animals for Blackwell. He is cur- MA 01923. For those organizations that have been granted a pho- rently Professor Emeritus of Zoological Medicine, University of tocopy license by CCC, a separate system of payments has been California-Davis. For the past four years he has been a part-time arranged. The fee codes for users of the Transactional Reporting employee of Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey’s Circus. Service are ISBN-13: 978-0-8138-0676-1; ISBN-10: 0-8138-0676- 3/2006 $.10. Susan K. Mikota is a co-founder of Elephant Care International and the Director of Veterinary Programs and Research. She is an First edition, 2006 author of Medical Management of the Elephants and numerous arti- cles and book chapters on elephant healthcare and conservation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © 2006 Blackwell Publishing Elephant biology, medicine, and surgery / edited by Murray E. All rights reserved Fowler, Susan K. Mikota.—1st ed. -

The South and South East Asian Ivory Markets. (2002)

© Esmond Martin and Daniel Stiles, March 2002 All rights reserved ISBN No. 9966-9683-2-6 Front cover photograph: These three antique ivory figurines of a reclining Buddha (about 50 cm long) with two praying monks were for sale in Bangkok for USD 34,000 in March 2001. Photo credit: Chryssee Martin Published by Save the Elephants, PO Box 54667, Nairobi, Kenya and 7 New Square, Lincoln’s Inn, London WC2A 3RA, United Kingdom. Printed by Majestic Printing Works Ltd., PO Box 42466, Nairobi, Kenya. Acknowledgements Esmond Martin and Daniel Stiles would like to thank Save the Elephants for their support of this project. They are also grateful to Damian Aspinall, Friends of Howletts and Port Lympne, The Phipps Foundation and one nonymous donor for their financial contributions without which the field-work in Asia would not have been possible. Seven referees — lain Douglas-Hamilton, Holly Dublin, Richard Lair, Charles McDougal, Tom Milliken, Chris Thouless and Hunter Weiler — read all or parts of the manuscript and made valuable corrections and contributions. Their time and effort working on the manuscript are very much appreciated. Thanks are also due to Gabby de Souza who produced the maps, and Andrew Kamiti for the excellent drawings. Chryssee Martin assisted with the field-work in Thailand and also with the report which was most helpful. Special gratitude is conveyed to Lucy Vigne for helping to prepare and compile the report and for all her help from the beginning of the project to the end. The South and South East Asian Ivory Markets Esmond Martin and Daniel Stiles Drawings by Andrew Kamiti Published by Save the Elephants PO Box 54667 c/o Ambrose Appelbe Nairobi 7 New Square, Lincoln’s Inn Kenya London WC2A 3RA 2002 ISBN 9966-9683-2-6 1 Contents List of Tables.................................................................................................................................... -

The Odyssey of Elephant: Contemporary Images and Representation

The Odyssey of Elephant: Contemporary Images and Representation The Odyssey of Elephant: Contemporary Images and Representation ดร.รัฐพล ไชยรัตน์* Abstract The Odyssey of Elephants: Contemporary Images and Represen- tation examines how we see and bring animal images into “our ” envi- ronment. We “re-create” superficial information about animals, such as elephants and other endangered species, to entertain and to educate ourselves. We also “re-create” their nature and the animals habitat. The information that we know about them is projected in the world through media and technology. Introduction This research is aimed at creating a body of work that communi- cates, in digital and video imagery, key issues around the representation of elephants. To develop this work I will investigate the changing role of the elephant in Thai culture both in historic and contemporary terms and explore the impact of imported ideas on the process of change. A signifi- *ดร.รัฐพล ไชยรัตน์ : คณะวิทยาการจัดการและสารสนเทศ มหาวิทยาลัยนเรศวร 26 The Odyssey of Elephant: Contemporary Images and Representation cant corollary interest in this research is the problem of representation and simulation in contemporary life and the impact it has on perception. My art work is a fabricated simulation created from material images. The animal images are transformed into illusions and explore how humans experience nature through simulation. In this way I engage with different kinds of rep- resentation for their specific forms and effects. Therefore considers the role of the elephant in Thailand. The use of the physicality of the elephant forms a key narrative that underpins the de- velopment of the nation through times of warfare, through to industrializa- tion and engagement with the West. -

(2020) Future of Thailand's Captive Elephants

van de Water, Antoinette; Henley, Michelle; Bates, Lucy; and Slotow, Rob (2020) Future of Thailand's captive elephants. Animal Sentience 28(18) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1579 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Sentience 2020.326: Van de Water et al. on Baker & Winkler on Elephant Rewilding Future of Thailand's captive elephants Commentary on Baker & Winkler on Elephant Rewilding Antoinette van de Water School of Life Sciences, University of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa Michelle Henley Applied Behavioural Ecology and Ecosystem Research Unit, University of South Africa Lucy Bates School of Psychology, University of Sussex Rob Slotow School of Life Sciences, University of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa Abstract: Removal from natural habitat and commodification as private property compromise elephants’ broader societal value. Although we support Baker & Winkler’s (2020) plea for a new community-based rewilding conservation model focused on mahout culture, we recommend an expanded co-management approach to complement and enhance the regional elephant conservation strategy with additional local community stakeholders and the potential to extend across international borders into suitable elephant habitat. Holistic co-management approaches improve human wellbeing and social cohesion, as well as elephant wellbeing, thereby better securing long-term survival of Asian elephants, environmental justice, and overall sustainability. Antoinette van de Water is a PhD researcher, University of Kwazulu-Natal, Director of Bring the Elephant Home, and a Director of the Elephant Specialist Advisory Group of South Africa. -

Wildlife on a Tightrope

Wildlife on a tightrope An overview of wild animals in entertainment in Thailand We were known as WSPA (World Society for the Protection of Animals) 1 Contents 03 Executive summary 35 Life in captivity for tigers 07 Animal welfare 36 Life in captivity for macaques 11 Wild animals in focus: elephants, tigers, macaques 41 Conclusion 26 Methodology and ranking definitions 45 How we can work with you 28 Results and observations 46 References 30 Life in captivity for elephants 47 Appendices Cover image Elephant walking on tightropes Unless otherwise stated, all images are World Animal Protection This research was supported by a grant from The Intrepid Foundation. 2 Executive summary A life in tourist entertainment Understanding the scale of is no life for a wild animal suffering Across the world, and throughout Asia, wild animals are being This report highlights the findings of our 2010 research into the lives of taken from the wild, or bred in captivity, to be used in the tourism captive wild animals used in tourism entertainment venues in Thailand entertainment industry. They will suffer at every stage of this – one of Asia’s most popular tourist destinations. inherently cruel process and throughout their lives in captivity. We assessed the scale of the wildlife tourism entertainment industry Wild animals taken from the wild, and from their mothers, are and reviewed how much, or how little regard for welfare was given being forced to endure cruel and intensive training to make them to captive wild animals at entertainment venues. perform, and to interact with people. They are living their whole lives in captive conditions that cannot meet their needs: a life in We wanted this information to help governments, communities, local tourist entertainment is no life for a wild animal.