Brian J Quinn Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's Digital Media Company

Annual Report and Accounts 2010 Annual Report and Accounts Scotland’s digital media company 2010 STV Group plc STV Group plc In producing this report we have chosen production Pacific Quay methods which aim to minimise the impact on our Glasgow G51 1PQ environment. The papers chosen – Revive 50:50 Gloss and Revive 100 Uncoated contain 50% and 100% recycled Tel: 0141 300 3000 fibre respectively and are certified in accordance with the www.stv.tv FSC (Forest stewardship Council). Both the paper mill and printer involved in this production are environmentally Company Registration Number SC203873 accredited with ISO 14001. Directors’ Report Business Review 02 Highlights of 2010 04 Chairman’s Statement 06 A conversation with Rob Woodward by journalist and media commentator Ray Snoddy 09 Chief Executive’s Review – Scotland’s Digital Media Company 10 – Broadcasting 14 – Content 18 – Ventures 22 KPIs 2010-2012 24 Performance Review 27 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 29 Corporate Social Responsibility Corporate Governance 34 Board of Directors 36 Corporate Governance Report 44 Remuneration Committee Report Accounts 56 STV Group plc Consolidated Financial Statements – Independent Auditors’ Report 58 Consolidated Income Statement 58 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 59 Consolidated Balance Sheet 60 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 61 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 62 Notes to the Financial Statements 90 STV Group plc Company Financial Statements – Independent Auditors’ Report 92 Company Balance Sheet 93 Statement -

Independent Television Producers in England

Negotiating Dependence: Independent Television Producers in England Karl Rawstrone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries, University of the West of England, Bristol November 2020 77,900 words. Abstract The thesis analyses the independent television production sector focusing on the role of the producer. At its centre are four in-depth case studies which investigate the practices and contexts of the independent television producer in four different production cultures. The sample consists of a small self-owned company, a medium- sized family-owned company, a broadcaster-owned company and an independent- corporate partnership. The thesis contextualises these case studies through a history of four critical conjunctures in which the concept of ‘independence’ was debated and shifted in meaning, allowing the term to be operationalised to different ends. It gives particular attention to the birth of Channel 4 in 1982 and the subsequent rapid growth of an independent ‘sector’. Throughout, the thesis explores the tensions between the political, economic and social aims of independent television production and how these impact on the role of the producer. The thesis employs an empirical methodology to investigate the independent television producer’s role. It uses qualitative data, principally original interviews with both employers and employees in the four companies, to provide a nuanced and detailed analysis of the complexities of the producer’s role. Rather than independence, the thesis uses network analysis to argue that a television producer’s role is characterised by sets of negotiated dependencies, through which professional agency is exercised and professional identity constructed and performed. -

Sci-Fi Sisters with Attitude Television September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE!

April 2021 Sky’s Intergalactic: Sci-fi sisters with attitude Television www.rts.org.uk September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE! R o y a l T e l e v i s i o n S o c i e t y b u r s a r i e s o f f e r f i n a n c i a l s u p p o r t a n d m e n t o r i n g t o p e o p l e s t u d y i n g : TTEELLEEVVIISSIIOONN PPRROODDUUCCTTIIOONN JJOOUURRNNAALLIISSMM EENNGGIINNEEEERRIINNGG CCOOMMPPUUTTEERR SSCCIIEENNCCEE PPHHYYSSIICCSS MMAATTHHSS F i r s t y e a r a n d s o o n - t o - b e s t u d e n t s s t u d y i n g r e l e v a n t u n d e r g r a d u a t e a n d H N D c o u r s e s a t L e v e l 5 o r 6 a r e e n c o u r a g e d t o a p p l y . F i n d o u t m o r e a t r t s . o r g . u k / b u r s a r i e s # R T S B u r s a r i e s Journal of The Royal Television Society April 2021 l Volume 58/4 From the CEO It’s been all systems winners were “an incredibly diverse” Finally, I am delighted to announce go this past month selection. -

![Statement 2011 [FINAL]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9394/statement-2011-final-1129394.webp)

Statement 2011 [FINAL]

Statement 2011 Overall strategy / major themes for the year STV continues to thrive as Scotland’s most popular peak time TV station and holds the broadcast licences for central and north Scotland, attracting more than 4 million viewers each month. With a strong, recognisable brand and a flourishing production arm we enter 2011 in the best position possible to create and deliver and unique, rich and relevant schedule for our viewers. 2011 will see Scotland complete its digital switchover process which has already been achieved successfully in the STV north region. This brings increased choice to all viewers including a DTT HD version of STV, the result of new investment in order to offer Scotland’s most popular peaktime service at the highest resolution. The digital business has been a huge success for STV over the past 12 months and we are looking forward to bolstering this throughout 2011 and further cementing STV’s reputation as Scotland’s digital media company. Remaining at the core of STV’s strategy is our ongoing commitment to our quality content and making that content available to our audiences whenever, wherever and however they want it through our STV Anywhere program. We offer Scottish viewers a service that is both relevant and unique to Scotland and increasingly available on multi platforms including DTT, DSAT & DCAB and HD. To complement our on air transmissions, we are developing new access for viewers via online websites such as the STV Player and YouTube and serving content to mobile and connected devices starting with iPhone apps and PS3 consoles. -

MI CV WORD April 2020

Giancarlo Dellapina Production Sound Mixer Mobile: +44 (0)7785572229 E Mail [email protected] FEATURE FILMS Fred Films , Powder Keg Pictures “Fishermans Friends” Director; Chris Foggin Tuppence Middleton, Daniel Mays Producer; Mike O’Regan DOP; Simon Tindall Koliko Films “Military Wives” Director; Peter Cattaneo Main & 2nd Unit Dailies Kristen Scott Thomas, Sharon Horgan Producer; Rene Besson DOP; Hubert Taczanowski Marvel, Supreme Works “Dr Strange” Director; Jeff Habberstad 2nd Unit Benedict Cumberbatch Producer; Kevin Feige DOP; Fraser Taggart Phantom Thread LTD “Phantom Thread” Daniel Day Lewis Director: Paul Thomas Anderson 2nd Unit Lesley Manville Producer: Peter Heslop DOP: Paul Thomas Anderson Mistletoe Pictures LTD “Nutcracker And The Four Realms” Director: Lasse Hallstrom 2nd Unit Keira Knightley, Morgan Freeman, Helen Mirren Producer: Paige Chaytor DOP: Linus Sandgren Playmaker Films “Palio” Alexa Director; Cosima Spender Documentary Feature about the historic Palio of Siena Producer; James Gay-Rees Winner Best Editing in Documentary Tribeca DOP; Stuart Bentley Yellow Sun Ltd/BFI “Half Of A Yellow Sun” 35mm, Loc Nigeria Director: Biyi Bandele Chiwitel Ejiofor, Thandie Newton, John Boyega Producer: Andrea Calderwood DOP; John De Borman SIP UK LTD “Snow In Paradise” Alexa Director; Andrew Hulme Fred Schmidt, Martin Askew, Aymen Hamdouchi Line Producer: Vanessa Tovell Nominated at Cannes, Un Certain Regard DOP; Mark Wolf Bread Street Films “Blackwood” Red Epic Director: Adam Wimpenny Ed Stoppard, Sophia Myles, Greg Wise, Joanna -

STV Review 2012 Overall Strategy / Major Themes for the Year STV Has

STV Review 2012 Overall Strategy / Major Themes for the Year STV has confirmed its place at the heart of communities and the creative industries in Scotland in 2012. The signing of new Channel 3 networking arrangements with ITV and the Secretary of State’s recommendation, in November to permit the long term renewal of the Channel 3 licences to STV in Central and North of Scotland has provided a strong platform for us to enhance the consumer experience and further build the STV brand. STV is committed to delivering high quality public service content that not only informs but engages its audience. It is imperative that we deliver a schedule that is distinct and relevant to Scotland, reflecting the cultural, political, sporting and wider differences that make the country unique. Our focus is to create and deliver a distinct schedule for viewers in Scotland - combining the best Channel 3 network material with a diverse range of original, relevant Scottish productions. STV reaches an average of 94% of Scots over the course of a month and on average attracts a higher audience share at peak time than the ITV network. STV News at Six is also currently achieving its highest audience share figures for 10 years. These are all clear indicators that STV is delivering programmes that are relevant and engaging for audiences across Scotland. Throughout 2012, STV’s transition from a traditional broadcaster to a digital media company has continued to develop as we make content readily available and free across multiple platforms anytime, anywhere. The creation of innovative, high quality and relevant material across new platforms remains key to our business and we continue to work with partners to deliver unique, compelling content wherever and whenever our consumers choose to access it. -

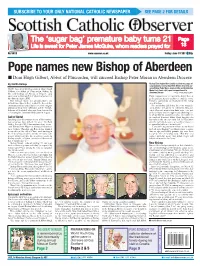

Pope Names New Bishop of Aberdeen � Dom Hugh Gilbert, Abbot of Pluscarden, Will Succeed Bishop Peter Moran in Aberdeen Diocese

SUBSCRIBE TO YOUR ONLY NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER SEE PAGE 2 FOR DETAILS No 5289 The ‘sugar bag’ premature baby turns 21 Page Life is sweet for Peter James McGuire, whom readers prayed for 13 No 5419 www.sconews.co.uk Friday June 10 2011 | 90p Pope names new Bishop of Aberdeen I Dom Hugh Gilbert, Abbot of Pluscarden, will succeed Bishop Peter Moran in Aberdeen Diocese By Martin Dunlop Bishop Elect Hugh Gilbert (main) received messages of congratulations from Cardinal Keith O’Brien (inset left), out- POPE Benedict XVI has named Dom Hugh going Bishop Peter Moran (inset middle) and Archbishop Gilbert, the abbot of Pluscarden Abbey, as Mario Conti (inset right) upon his appointment to the new bishop of Aberdeen Diocese and Aberdeen Diocese PICS: PAUL McSHERRY successor to Bishop Peter Moran who has led Hugh’s appointment is a loss to the abbey, there is the diocese since 2003. great gain for Aberdeen Diocese and the wider The Vatican made the announcement last Catholic community of Scotland in his being Saturday and Dom Gilbert, head of the Benedictine named bishop.” community at Pluscarden, has received the congrat- The archbishop added that the news would be ulations of his priestly colleagues and the Catholic ‘particularly welcomed in Aberdeen Diocese, bishops of Scotland, who now look forward to where Pluscarden has warm links with every part celebrating his Episcopal Ordination in August. of the territory and is recognised as a thriving cen- tre of spirituality, monastic practice and culture in Call of Christ the north of Scotland. Abbot Hugh has played a Speaking after the announcement of his nomina- key role in the success story that is Pluscarden tion as bishop, Dom Gilbert, 59, said: “The Holy over the last few decades, a period which has seen Father, Benedict XVI, has nominated me to suc- it expand its influence far and wide.’ ceed Bishop Peter Moran as bishop of Aberdeen. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Accounts and Report Annual

Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Accounts and Report Annual Annual Report and Accounts 2017 STV Group plc Contents 01 2017 financial and Financial Statements operational highlights 76 STV Group plc consolidated financial statements Strategic Report – independent auditors’ report 02 The STV Family 82 Consolidated income statement 04 Chairman’s statement 82 Consolidated statement Operating review 06 of comprehensive income – Group 83 Consolidated and parent – Consumer company balance sheets – Showcase of STV content 84 Consolidated and parent – Productions company statement of – STV External Lottery Manager changes in equity 22 Corporate responsibility 85 Consolidated and parent STV Children’s Appeal 2017 29 company statement Performance review 32 of cash flows 34 Principal risks and uncertainties 86 Notes to the financial statements 36 Risk management 113 Five year summary Governance Additional Information 39 Introduction to governance 114 Shareholder information 40 Board of Directors 116 Notice of Annual General Meeting 42 Corporate governance report 55 Remuneration report 72 Directors’ report STV is Scotland’s leading digital media brand, providing consumers with quality content on air, online and on demand. View our Annual Report and Accounts and other information about STV at www.stvplc.tv STV Annual Report and Accounts 2017 2017 financial and operational highlights Turnover Operating profit* (£ millions) (£ millions) 20.3 19.7 19.5 120.4 120.4 19.0 116.5 117.0 % % -3 2014 2015 2016 2017 -4 2014 2015 2016 2017 Dividends per share (pence) STV reaches 17.0 3.5m 15.0 10.0 viewers each month % 8.0 on channel 3 +13 2014 2015 2016 2017 +37% STV2 launches as in streams on Scotland’s newest channel the STV Player EPS* STV Children’s Appeal (pence) raises over £2.6m 39.7 39.9 39.6 38.7 Flat 2014 2015 2016 2017 * Pre-exceptionals and IAS 19. -

BA (Hons) Television

Please insert award – BA (Hons) Television PleaseMy Programme insert 2021/22the Programme Title 1 The Purpose of My Programme is to: Provide you with a source of information about your programme (which will be updated annually) and; Make you aware of some of the more important regulations under which your Programme operates. This document concentrates on Programme specific information. Members of your Programme Team (see section 4) will be happy to explain aspects in further detail as required. My Programme should be read alongside the My Napier resource, which contains useful information about the University as a whole. You can access My Napier at https://my.napier.ac.uk/ or by clicking any of the My Napier links in this document. The content of this My Programme is correct at the point of production however, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, some information may change. Please regularly check My Napier, student newsletters and university emails for important updates. For TNE provision there is a distinct My University handbook written for you and it replaces the My Napier references in this handbook. 2 1. Programme Leader Welcome Dr.Kirsten 0131 455 C5 [email protected] MacLeod 3343 As Programme Leader for BA Television, and on behalf of the BA (Hons) Television Programme Team, I would like to extend a very warm welcome to you. We look forward to working with you and supporting you during your time at Edinburgh Napier University. We hope you will be successful in your studies and make the most of all the opportunities that are available to you as a Napier student. -

Press Release 0700 Hours, 1 September 2020 STV Group Plc Half

RNS Number : 5533X STV Group PLC 01 September 2020 Press Release 0700 hours, 1 September 2020 STV Group plc Half Year Results to 30 June 2020 Strongly positioned to resume successful growth strategy • Proactive steps taken to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 and support STV colleagues and partners • Continued record viewing growth on TV and online as STV's public service broadcaster role is reinforced • Total advertising revenue trends improving materially: June -33%; July -7%; August +1% • Digital business accelerating rapidly with online viewing +86% • Significant new commissions secured by STV Studios, including new returnable drama series for C4 Proactive steps to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 • Balance sheet significantly strengthened to enable ongoing investment in STV's successful growth strategy: o Completion of share placing in July raising net proceeds of £15.5m o Extension of bank facilities from £60m to £80m • Swift implementation of full year cost and cash savings of £7m and £11m respectively, as well as postponement of pension contributions from Q2 to December • Focus in H1 has been on the safety of our colleagues and supporting our partners: all furloughed colleagues have been topped up to 100% of salary and we have reinforced our social purpose through the STV Children's Appeal, public health messaging, new diversity commitments and support for local advertisers Financial Performance •Total advertising revenue down 20%, with national down 23% and regional impacted to a lesser extent, down 18% • Digital revenues up 5%, -

STV Review 2011

STV Review 2011 Overall Strategy / Major Themes for the Year 2011 has been an exciting and busy year for STV. With the delivery of a high quality and vibrant schedule for viewers in Scotland and a clear commitment to public service broadcasting; the launch of a brand new charity; the continued roll-out of our STV Local initiative; launches of STV News and STV Player on multiple platforms; and a vast array of activities connecting STV with communities all over Scotland; STV is firmly at the heart of the creative industries in Scotland. STV is committed to providing an ambitious, distinct, relevant and up-to-the-minute local service for viewers across the country, using top-of-the-range broadcasting technology. For STV, this is about delivering a valued and first rate news service across multi-platforms that people know and trust, developing increased editorial content and being innovative in the way that we deliver public service broadcasting in a digital age. We have transformed STV from a traditional broadcaster to a digital media company that engages with consumers across multiple platforms offering unique delivery of Public Service Broadcasting and a compelling range of must-have digital services. We aim to connect with our viewers as active consumers of content across platforms. The creation of innovative, high quality and relevant content remains key to our business. We continue to work with partners to deliver unique, compelling content that can be accessed anywhere, anytime. Through 2011, STV has continued to extend its reach across Scotland. We delivered a schedule comprising the best Channel 3 Network material and strong home grown productions, alongside our dedicated and popular news service. -

Pulling the Levers for Growth +44 (0)20 7851 0906 [email protected]

Abi Watson +44 (0)20 7851 0902 STV [email protected] Jamie McGowan Stuart Pulling the levers for growth +44 (0)20 7851 0906 [email protected] Thomas Thomson • STV now has a clear pathway to reduce its reliance on +44 207 851 0903 [email protected] linear advertising by investing in production, while pushing the transition to digital forward with a UK- Gill Hind +44 (0)20 7851 0913 wide footprint [email protected] Tom Harrington • To that end, STV Player has some momentum and +44 (0)20 7851 0918 recent production company acquisitions, increasing [email protected] external commissions and PSB Out of London quotas should ensure STV Studios returns to growth in 2021 14 October 2020 • Such development is imperative: COVID-19 has accelerated structural change in viewing habits meaning now that content must not only be great, but available widely and immersed in a smooth user experience just to have a chance Figure 1: Viewer mins to STV-produced shows* and STV channel (bn) Related reports: ITV H1 2020 results: Clawing out of the 70 65.6 63.6 61.9 60.6 ravine [2020-082] 59.6 60.1 59.9 60 TV set viewing trends: 2020 lockdown and 50 full year 2019 [2020-073] 40 Broadcast television: Troubling trends in 28.1 30 lockdown [2020-058] 24.3 20.0 17.8 18.6 16.7 20 14.0 COVID-19 TV impact: Permanent change without intervention [2020-037] 10 19.4 20.7 14.0 17.8 18.6 16.5 18.4 0 Media consumption: the ‘surprising’ 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 endurance of broadcast media [2020-014] Repeats of Antiques Road Trip on Really STV-produced shows* (UK viewing) *Excludes STV-only programmes.