Full Article –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Integrated Analytical Approach to Define the Compositional And

minerals Article An Integrated Analytical Approach to Define the Compositional and Textural Features of Mortars Used in the Underwater Archaeological Site of Castrum Novum (Santa Marinella, Rome, Italy) Luciana Randazzo 1 , Michela Ricca 1 , Silvestro Ruffolo 1, Marco Aquino 2, Barbara Davidde Petriaggi 3, Flavio Enei 4 and Mauro F. La Russa 1,5,* 1 Department of Biology, Ecology and Earth Sciences (DiBEST), University of Calabria, 87036 Arcavacata di Rende, Cosenza, Italy; [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (M.R.); silvio.ruff[email protected] (S.R.) 2 Department of Environmental and Chemical Engineering (DIATIC), University of Calabria, 87036 Arcavacata di Rende, Cosenza, Italy; [email protected] 3 Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo—Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione e il Restauro, 00153 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 4 Museo del Mare e della Navigazione Antica, Castello di Santa Severa, 00058 S. Severa, Rome, Italy; [email protected] 5 Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, National Research Council, Via Gobetti 101, 40129 Bologna, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 March 2019; Accepted: 29 April 2019; Published: 30 April 2019 Abstract: This paper aims to carry out an archaeometric characterization of mortar samples taken from an underwater environment. The fishpond of the archaeological site of Castrum Novum (Santa Marinella, Rome, Italy) was chosen as a pilot site for experimentation. The masonry structures reached the maximum thickness at the apex of the fishpond (4.70 m) and consisted of a concrete conglomerate composed of slightly rough stones of medium size bound with non-hydraulic mortar. -

Sea Level Rise Scenario for 2100 AD in the Heritage Site of Pyrgi

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 17 October 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201910.0202.v1 Sea level rise scenario for 2100 A.D. in the heritage site of Pyrgi (Santa Severa, Italy) Marco Anzidei1, Fawzi Doumaz1, Antonio Vecchio2-3 Enrico Serpelloni1, Luca Pizzimenti1, Riccardo Civico1 and Flavio Enei4 1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Italy 2 Radboud Radio Lab, Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University - Nijmegen, The Netherlands 3 Lesia Observatoire de Paris, PSL Research University, Paris, France 4 Museo del Mare e della Navigazione Antica, Santa Severa, Italy Abstract Sea level rise is one of the main factor of risk for the preservation of cultural heritage sites located along the coasts of the Mediterranean basin. Coastal retreat, erosion and storm surges are yet posing serious threats to archaeological and historical structures built along the coastal zones of this region. In order to assess the coastal changes by the end of 2100 under an expected sea level rise of about 1 m, a detailed determination of the current coastline position and the availability of high resolution DSM, is needed. This paper focuses on the use of very high-resolution UAV imagery for the generation of ultra-high resolution mapping of the coastal archaeological area of Pyrgi, near Rome (Italy). The processing of the UAV imagery resulted in the generation of a DSM and an orthophoto, with an accuracy of 1.94 cm/pixel. The integration of topographic data with two sea level rise projections in the IPCC AR5 2.6 and 8.5 climatic scenarios for this area of the Mediterranean, were used to map sea level rise scenarios for 2050 and 2100. -

PCE Schede E Modelli

Redazione Aggiornamento del P.E.C. di Protezione Civile del Comune di Santa Marinella COMUNE DI SANTA MARINELLA Sindaco: Dott. Roberto Bacheca Segretario Generale: Dott. Alfonso Migliore Delegato alla protezione civile: Massimiliano Calvo PROTEZIONE CIVILE Corpo di Polizia Locale ‐ Protezione Civile Responsabile: Comandante Dott. Mario Adinolfi Protezione civile e ambiente: Vice Comandante Dott.ssa Keti Marinangeli REVISIONI Revisione 0 marzo 2015 Revisione 1 settembre 2015 Revisione 2 novembre 2016 Redazione: Marianna Architetto Cerillo Napoli ‐ [email protected] Consulenza geologica per CLE Dott. Geol. V. Sciuto, GTS Geologia – Civitavecchia (Roma) Contribuiti per la redazione del Piano Regione Lazio – Agenzia Regionale di Protezione Civile Ufficio Pianificazione Dott. Geol. A. Colombi Comune di Santa Marinella ‐ Ufficio tecnico manutentivo – Resp. Geom. D. Guidoni Comune di Santa Marinella ‐ Ufficio edilizia privata – Resp. Arch. C. Gentili GTS Geologia, Dott. Geol. V.Sciuto Web gis comunale ‐ Ing. F. Giansanti C.N.A.M.C.A. di Pratica di Mare M.llo S. Prudenzi Associazione di Volontariato Nucleo Sommozzatori, Resp. P. Ballarini Associazione di Volontariato Pro Pyrgi, Resp. M. Guredda Associazione di Volontariato Rangers d’Italia, Resp. L. Astori Croce Rossa Italiana ‐ Comitato Locale di Santa Severa‐Santa Marinella, Presidente F. Napolitano Croce Rossa Italiana ‐ Comitato Locale di Santa Severa‐Santa Marinella D. T. Area III R. Luccisano Misericordia Santa Marinella – Governatore G. d’Orinzi INDICE 1. Dati di base 2. Scenari -

Bioarchaeological Approach to the Study of the Medieval Population of Santa T Severa (Rome, 7Th–15Th Centuries)

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 18 (2018) 11–25 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Bioarchaeological approach to the study of the medieval population of Santa T Severa (Rome, 7th–15th centuries) Micaela Gnesa,1, Marica Baldonia,b,1, Lorenza Marchettia, Francesco Basolic, Donatella Leonardid, ⁎ Antonella Caninid, Silvia Licocciae, Flavio Eneif, Olga Rickardsg, Cristina Martínez-Labargaa,g, a Laboratorio di Biologia dello Scheletro e Antropologia Forense, Dipartimento di Biologia, Università degli Studi di Roma “Tor Vergata”, Via della Ricerca Scientifica n. 1, 00173 Roma, Italy b Laboratorio di Medicina Legale, Dipartimento di Biomedicina e Prevenzione, Università degli Studi di Roma “Tor Vergata”, Via Montpellier n. 1, 00173 Roma, Italy c Tissue Engineering Unit, Università Campus Bio-Medico di Roma, Via Álvaro del Portillo 21, 00128 Roma, Italy d Dipartimento di Biologia, Università degli Studi di Roma “Tor Vergata”, Via della Ricerca Scientifica 1, 00173 Roma, Italy e Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Chimiche, Università degli Studi di Roma “Tor Vergata”, Via della Ricerca Scientifica 1, 00173 Roma, Italy f Museo Civico di Santa Marinella “Museo del Mare e della Navigazione Antica” Castello di Santa Severa, Roma, Italy g Centro di Antropologia Molecolare per lo Studio del DNA antico, Dipartimento di Biologia, Università degli Studi di Roma “Tor Vergata”, Via della Ricerca Scientifica n. 1, 00173 Roma, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The present research utilizes archaeology and physical anthropology to reconstruct the demography, occupa- Medieval era tional stress markers and health conditions of individuals that lived during the medieval era in Santa Severa Osteobiography (Rome, Italy). -

Sea Level Rise Scenario for 2100 A.D. in the Heritage Site of Pyrgi (Santa Severa, Italy)

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Sea Level Rise Scenario for 2100 A.D. in the Heritage Site of Pyrgi (Santa Severa, Italy) Marco Anzidei 1,*, Fawzi Doumaz 1 , Antonio Vecchio 2,3 , Enrico Serpelloni 1, Luca Pizzimenti 1, Riccardo Civico 1 , Michele Greco 4 , Giovanni Martino 4 and Flavio Enei 5 1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, 56126 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] (F.D.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (L.P.); [email protected] (R.C.) 2 Radboud Radio Lab, Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University— Nijmegen, 6500GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Lesia Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Université de Paris, 92195 Meudon, France 4 School of Engineering, Università della Basilicata, 85100 Potenza, Italy; [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (G.M.) 5 Museo del Mare e della Navigazione Antica, 00058 Santa Severa, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 November 2019; Accepted: 15 January 2020; Published: 21 January 2020 Abstract: Sea level rise is one of the main risk factors for the preservation of cultural heritage sites located along the coasts of the Mediterranean basin. Coastal retreat, erosion, and storm surges are posing serious threats to archaeological and historical structures built along the coastal zones of this region. In order to assess the coastal changes by the end of 2100 under the expected sea level rise of about 1 m, we need a detailed determination of the current coastline position based on high resolution Digital Surface Models (DSM). -

The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria

Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Tirol The cities and cemeteries of Etruria Dennis, George 1883 Contents of Volume I urn:nbn:at:at-ubi:2-12107 CONTENTS OF VOLUME I. INTRODUCTION. PAGI Kecent researches into the inner life of the Etruscans —Nature of the docu¬ ments whence our knowledge is acquired —Monumental Chronicles—Object of this work to give facts, not theories—Geographical position and extent of Etruria —Its three grand divisions—Etruria Proper , its boundaries and geological features —The Twelve Cities of the Confederation—Ancient and modern condition of the land—Position of Etruscan cities —Origin of the Etruscan race—Ancient traditions —Theories of Niebuhr , Muller , Lepsius, and others—The Lydian origin probable —Oriental character of the Etrus¬ cans—Analogies in their religion and customs to those of the East —Their language still a mystery —The Etruscan alphabet and numerals —Govern¬ ment of Etruria —Convention of her princes—Lower orders enthralled-1— Religion of Etruria , its effects on her political and social state—Mytho¬ logical system—The Three great Deities—The Twelve Dii Consentes—The shrouded Gods—The Nine thunder -wielding Gods—Other divinities —Fates —Genii—Lares and Lasas—Gods of the lower world—Extent and nature of Etruscan civilization —Literature —Science—Commerce—Physical con¬ veniences—Seweiage—Roads—Tunnels—Luxury —The Etruscans superior to the Greeks in their treatment of woman—Arts of Etruria —Architecture —To be learned chiefly from tombs—Walls of cities—Gates—The arch in Italy worked out by the Etruscans -

Etruscan Italy

Etruscan italy as seen by students Study Materials ENGLISH VERSION Brno 2018 EDITORS Anna Krčmářová, Tomáš Štěpánek, Klára Matulová, Věra Klontza-Jaklová Published only in the electronic form. These study materials are available on the webpage of ÚAM MU Brno (http://archeo-muzeo.phil.muni.cz/). These study materials were created under the auspices of Masaryk University at Department of Archeology and Museology within the grant project FRMU MUNI / FR / 1298/2016 (ID = 36283). Etruscan italy as seen by students Excursion participants, Volterra 2017. ENGLISH VERSION Brno 2018 Introduction The excursion to Italy was held from 29th May till 7th June 2017 and was organized by students of Department of Archaeology and Museology of Masaryk University in Brno. The main intention was to present the Etruscan landscape in its natural settings to students of Classical Archaeology and related fields of study. The excursion took place within the grant project FRMU ID-MUNI / FR / 1298/2016 (ID = 36283). This excursion completed following Classical Archaeology courses: AEB_74 (Etruscan and Central Europe) and KLBcA25 (Etruscans in the context of Ancient World - Etruscology), KLMgrA31 (Excursion) but it was considerably valuable as well for students of History and Ancient history. All students had to be active in the period of its organization in order to complete the course and get the credits. Before the field trip, they had to attend a seminar to get acquainted with each visited site and the individual essay’s topics have been shared with students. The selection of topics was based on their own interest. Students were allowed to work in smaller groups or completely independently. -

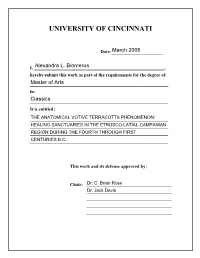

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ THE ANATOMICAL VOTIVE TERRACOTTA PHENOMENON : HEALING SANCTUARIES IN THE ETRUSCO-LATIAL-CAMPANIAN REGION DURING THE FOURTH THROUGH FIRST CENTURIES B.C. A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 1999 by Alexandra L. Lesk Blomerus B.A., Dartmouth College, 1995 M.St., University of Oxford, 1996 Committee: Professor C. Brian Rose (Chair) Professor Jack L. Davis 1 ABSTRACT At some point in the fourth century B.C., anatomical votive terracottas began to be dedicated in sanctuaries in central Italy. Thousands of replicas of body parts have been found in votive deposits in these sanctuaries, left to deities as requests or thank offerings for healing. The spread of the anatomical votive terracotta phenomenon has been attributed to the colonisation of central Italy by the Romans. In addition, parallels have been drawn to the similar short-lived phenomenon at the Asklepieion at Corinth where models of body parts were also dedicated in the context of a healing cult. After a general introduction to the historical and physical context of the anatomical votive terracotta phenomenon, this thesis examines the link to Corinth and suggests how the practice was first transmitted to Italy. Votive evidence of early date and peculiar typology found in situ from the sanctuary at Gravisca on the south coast of Etruria suggests contact with Greeks who would have been familiar with the practice of dedicating anatomical votive terracottas at Corinth. -

The Sanctuary at Grasceta Dei Cavallari As a Case-Study of the E-L-C Votive Tradition in Republican Italy

Actors and Agents in Ritual Behavior: The Sanctuary at Grasceta dei Cavallari as a Case-Study of the E-L-C Votive Tradition in Republican Italy by Kevin D‘Arcy Dicus A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Nicola Terrenato, Chair Professor Elaine K. Gazda Professor Carla M. Sinopoli Professor Janet E. Richards © Kevin D‘Arcy Dicus 2012 Alla gente di Tolfa e ai miei genitori che potrebbero essere bravi tolfetani ii Acknowledgements The acknowledgements are conventionally the final addendum to the dissertation. These opening lines signal the closure of the magnum opus which has been defended, revised, formatted; it is primed for its formal inclusion in the high society of academic discourse, as if being presented at the dissertation debutante ball. The passage to this ultimate stage, from the incipient twinkle in the author‘s cerebral cortex, is littered with the corpses of euthanized chapters and passages, made blurry by sleepless nights and paludal from sweat and tears. All of the struggles make the conclusion of the labor that much more rewarding. The acknowledgments allow for what William Wordsworth called ―emotion recollected in tranquility.‖ I would not consider tranquility to be a defining characteristic of the dissertation process. Its completion, however, has allowed me to find some refuge in this unfamiliar state where I am able to reflect back on the past years and recollect not only the struggles but also the people and experiences that made this project the most valuable and memorable time of my life. -

Relative Sea Level Change at the Archaeological Site of Pyrgi (Santa Severa, Rome) During the Last Seven Millennia

Quaternary International xxx (2010) 1e10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Relative sea level change at the archaeological site of Pyrgi (Santa Severa, Rome) during the last seven millennia Rovere Alessio a,*, Antonioli Fabrizio b, Enei Flavio c, Giorgi Stefano c a Dipartimento per lo Studio del Territorio e delle sue Risorse, Università degli Studi di Genova, Corso Europa 126, 16132 Genoa, Italy b ENEA, National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Environment, Rome, Italy c Museo del mare e della navigazione Antica, S. Severa, Roma, Italy article info abstract Article history: New data are presented for late Holocene relative sea level change for one of the older harbors of the Available online xxx Mediterranean Sea. Data are based on measurements of submerged archaeological remains, indicating past sea level and shoreline positions. The study has been carried out at Pyrgi (Santa Severa), an important Etruscan archaeological site located in central Italy, 52 km north of Rome. Underwater geomorphological features (a large shore platform) and archaeological remains (a Roman dock, two fishtanks, and wells of Etruscan age) connected to relative sea level and to the shoreline during the last 7 millennia have been measured and compared with current glacio-hydro-isostatic theoretical models in order to reconstruct the long-term shoreline evolution and to evaluate coastal tectonic vertical move- ments, so far derived for this area only from Last Interglacial (125 ka) sea level markers. Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. 1. Introduction The aims of this multidisciplinary research were to: i) measure geomorphological and archaeological sea level and paleoshoreline Sea level change is the sum of eustatic, glacio-hydro-isostatic markers; ii) compare them to the predicted sea level curves and tectonic factors (Waelbroek et al., 2002; Lambeck et al., 2004a). -

JM^^^.^^^^,^M&^T;^5^^C; 1

- At, b V-*/r" . f^^ TJ> 'imff^M &V/'V^' '.0;*8&** - /;* V u ^ ' V ^tfr^fStf?** ' .--.. i?^t -^ V r- ^r^Vfl CTbe ^tlniversi KlibraricjB '?9^.^'fi:.? 2'yr. , t /"'/^ ,"*Vo ^ ^s EXCHANGE ' ' ' ^/> ;* UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS - '">>' f 4^Jj..i* fta, v "- < i i..; i , ,'.,'' (Siiri?^ i^'/ f,'.' /,'-"; V ^V "'.:,;; ''.>," /J T fer^f ^ m>- ti! i>i^ * ;:-*;-&. telJM^^^.^^^^,^m&^T;^5^^c; 1 Jf/ fe l \ I', f ' '" '"'" : ; '. Jfg$& ;-;-;--r,:i^igis,^'> " ; ' "' ' ::-'' '. ' '^tt-fi'- v ','>'----';. vi' - '" -' > -..-;., v^t^wIRj .: : .', -^"^ffi-y'-'K... I ^ :>'-$$%S&:-3 : 'fox^n-Sfi -i< ...M fe LOCAL CVLTS IN ETRVRIA LOCAL CVLTS IN ETRVRIA BY LILY ROSS TAYLOR PAPERS AND MONOGRAPHS OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME VOLVAVE 11 AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME 1925 PRINTED IM ITALY PRINTED ROR THE AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME by ACCOM. EDITORI ALFIERI & LACROIX - ROMA Di LUIGI ALFIERI & C.o PREFACE. This monograph is a geographical study of the religious cults of Etruria. The available evidence from literary, epi~ graphical, and archaeological sources is collected and discussed independently for each town. The work is not a general study of Etruscan religion. Evidence for Etruscan religious beliefs and cult forms is considered only when it can be associated with a particular town. Yet the effort to reconstruct the re~ ligious history of the various cities will, it is hoped, contribute to a fuller understanding of the religion of the Etruscan peoples and will thus supplement the historical, linguistic, and archaeo" logical investigations that are gradually throwing