Learning Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asset Freezing Measures at the International Criminal Court and the UN Security Council

International international criminal law review Criminal Law 20 (2020) 983-1025 Review brill.com/icla Coexistent but Uncoordinated: Asset Freezing Measures at the International Criminal Court and the UN Security Council Daley J. Birkett Vice-Chancellor’s Senior Fellow, Northumbria Law School, Northumbria University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK; Amsterdam Center for International Law, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Both the International Criminal Court (icc) and the UN Security Council (unsc) are vested with the capacity to request States to freeze individuals’ assets. The two bodies are also bound to cooperate closely under the terms of their relationship agreement ‘with a view to facilitating the effective discharge of their respective responsibilities’. This article examines whether this obligation extends to the unsc coordinating its targeted sanctions regime to support the icc in respect of the enforcement powers with which the latter is equipped. It does so by analysing eight cases where unsc action (could) have coincided with icc operations, with a particular focus on the (non-)parallel implementation of the two bodies’ asset freezing procedures. The ar- ticle demonstrates that, though the activities of the unsc and the icc in this sphere of their respective operations might have overlapped on a number of occasions, they have rarely been deliberately coordinated. This leads the author to conclude that close cooperation as envisaged in the relationship agreement between the two bodies is un- likely on this front. Keywords asset freezing – International Criminal Court (icc) – UN Security Council (unsc) – peace and security – targeted sanctions – Rome Statute – UN Charter – icc-UN Relationship Agreement © DALEY J. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

Reconciling the Protection of Civilians and Host-State Support in UN Peacekeeping

MAY 2020 With or Against the State? Reconciling the Protection of Civilians and Host-State Support in UN Peacekeeping PATRYK I. LABUDA Cover Photo: Elements of the UN ABOUT THE AUTHOR Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s PATRYK I. LABUDA is a Postdoctoral Scholar at the (MONUSCO) Force Intervention Brigade Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a Non-resident and the Congolese armed forces Fellow at the International Peace Institute. The author’s undertake a joint operation near research is supported by the Swiss National Science Kamango, in eastern Democratic Foundation. Republic of the Congo, March 20, 2014. UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper represent those of the author The author wishes to thank all the UN officials, member- and not necessarily those of the state representatives, and civil society representatives International Peace Institute. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide interviewed for this report. He thanks MONUSCO in parti - range of perspectives in the pursuit of cular for organizing a workshop in Goma, which allowed a well-informed debate on critical him to gather insights from a range of stakeholders.. policies and issues in international Special thanks to Oanh-Mai Chung, Koffi Wogomebou, Lili affairs. Birnbaum, Chris Johnson, Sigurður Á. Sigurbjörnsson, Paul Egunsola, and Martin Muigai for their essential support in IPI Publications organizing the author’s visits to the Central African Adam Lupel, Vice President Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Albert Trithart, Editor South Sudan. The author is indebted to Namie Di Razza for Meredith Harris, Editorial Intern her wise counsel and feedback on various drafts through - out this project. -

Annex to Notice

ANNEX TO NOTICE FINANCIAL SANCTIONS: DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 1275/2014 AMENDING ANNEX I TO COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 1183/2005 REGIME: Democratic Republic of the Congo ADDITIONS Entity 1. ADF a.k.a: (1) ADF/NALU (2) Forces Democratiques Alliees-Armee Nationale de Liberation de l'Ouganda (3) Islamic Alliance of Democratic Forces Address: North Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Other Information: Created in 1995 and is located in the mountainous DRC-Uganda border area. The ADF's military commander is Hood LUKWAGO and its supreme leader is the sanctioned individual Jamil MUKULU. Group ID: 13189. DELISTING Entity 1. GREAT LAKES BUSINESS COMPANY (GLBC) Address: (1) Gisenyi, Rwanda. (2) PO Box 315, Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Other Information: Owned by Douglas Mpamo. As of Dec 2008, GLBC no longer had any operational aircraft, although several aircraft continued flying in 2008 despite UN sanctions. Group ID: 9071. Note this entity has been merged with COMPAGNIE AERIENNE DES GRANDS LACS (CAGL) – see amended entry below AMENDMENTS Additions are shown in italics and underlined. Deleted text is shown in strikethrough. INDIVIDUALS 1. BADEGE, Eric Title: LT. Colonel DOB: --/--/1971. Group ID: 12838. i 2. IYAMUREMYE, Gaston Title: Brigadier General DOB: --/--/1948. POB: (1) Musanze District (Northern Province) (1) Musanze District, Northern Province, Rwanda (2) Ruhengeri, (1) Rwanda (2) Ruhengeri, Rwanda a.k.a: (1) BYIRINGIRO, Michel (2) RUMULI, Byiringiro, Victor (3) RUMURI, Victor Nationality: Rwandan Address: Kalonge, North Kivu Province (as of June 2011). Position: FDLR President and 2nd Vice-President of FDLR-FOCA Other Information: Also referred to as Rumuli. -

Le Président Du Conseil De Sécurité Présente

Le Président du Conseil de sécurité présente ses compliments aux membres du Conseil et a l'honneur de transmettre, pour information, le texte d'une lettre datée du 2 juin 2020, adressée au Président du Conseil de sécurité, par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo reconduit suivant la résolution 2478 (2019) du Conseil de sécurité, ainsi que les pièces qui y sont jointes. Cette lettre et les pièces qui y sont jointes seront publiées comme document du Conseil de sécurité sous la cote S/2020/482. Le 2 juin 2020 The President of the Security Council presents his compliments to the members of the Council and has the honour to transmit herewith, for their information, a copy of a letter dated 2 June 2020 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2478 (2019) addressed to the President of the Security Council, and its enclosures. This letter and its enclosures will be issued as a document of the Security Council under the symbol S/2020/482. 2 June 2020 UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS-ADRESSE POSTALE: UNITED NATIONS, N.Y. 10017 CABLE ADDRESS -ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: UNATIONS NEWYORK REFERENCE: S/AC.43/2020/GE/OC.171 2 juin 2020 Monsieur Président, Les membres du Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo, dont le mandat a été prorogé par le Conseil de sécurité dans sa résolution 2478 (2019), ont l’honneur de vous faire parvenir leur rapport final, conformément au paragraphe 4 de ladite résolution. -

From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Transition in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’

paper 50 From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Transition in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) by Björn Aust and Willem Jaspers Published by ©BICC, Bonn 2006 Bonn International Center for Conversion Director: Peter J. Croll An der Elisabethkirche 25 D-53113 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-911960 Fax: +49-228-241215 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bicc.de Cover Photo: Willem Jaspers From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Table of contents Summary 4 List of Acronyms 6 Introduction 8 War and war economy in the DRC (1998–2002) 10 Post-war economy and transition in the DRC 12 Aim and structure of the paper 14 1. The Congolese peace process 16 1.1 Power shifts and developments leading to the peace agreement 17 Prologue: Africa’s ‘First World War’ and its war economy 18 Power shifts and the spoils of (formal) peace 24 1.2 Political transition: Structural challenges and spoiler problems 29 Humanitarian Situation and International Assistance 30 ‘Spoiler problems’ and political stalemate in the TNG 34 Systemic Corruption and its Impact on Transition 40 1.3 ‘Violent peace’ and security-related liabilities to transition 56 MONUC and its contribution to peace in the DRC 57 Security-related developments in different parts of the DRC since 2002 60 1.4 Fragility of security sector reform 70 Power struggles between institutions and parallel command structures 76 2. A Tale of two cities: Goma and Bukavu as case studies of the transition in North and South Kivu -

Sylvestre MUDACUMURA

Le Bureau du Procureur The Office of the Prosecutor FACTSHEET Situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Sylvestre MUDACUMURA 14 May 2012 1 / 5 PROFILE – Sylvestre MUDACUMURA génocidaires re-grouped within refugee camps in the DRC, organized themselves and launched attacks in Rwanda, with the goal of removing its then new Government by force. The FDLR was involved in the two Congo wars, from 1996 until 2003, that caused, directly or indirectly, an estimated 4 million 1 victims. This is the largest single number of conflict-related civilian deaths since the Name: MUDACUMURA, Sylvestre Second World War. Also know as: “Bernard Mupenzi”, Since 2002, the FDLR has been committing “Mpezi”, “Commandant Pharaon” or crimes against civilians. The Security Council has consistently characterized the “Pharaoh”, “Mudac”, “Mukanda” or FDLR as a threat to the peace and security of “Radja” the Great Lakes region, a cause of regional Sex: Male insecurity and instability and a threat to the Year of Birth: 1954 local civilian population. Location of Birth: Gatumba sector, Sylvestre MUDACUMURA is a member of Gisenyi prefecture, Rwanda the FDLR’s Steering Committee and head of Nationality: Rwandan the FDLR military wing. As Supreme Current Position: Supreme Commander Commander of the Army and President of its of the Army and President of the High High Command, MUDACUMURA is the Command of the Forces Démocratiques highest-ranking military commander in the pour la Libération du Rwanda – Forces FDLR. He is subject to UN and EU sanctions. Combattantes Abacunguzi (FDLR – FOCA) Relevant Background Information Mr. Sylvestre MUDACUMURA is the supreme commander of the FDLR. -

Legacies of the Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial After 70 Years

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 39 Number 1 Special Edition: The Nuremberg Laws Article 7 and the Nuremberg Trials Winter 2017 Legacies of the Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial After 70 Years Hilary C. Earl Nipissing University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Recommended Citation Hilary C. Earl, Legacies of the Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial After 70 Years, 39 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 95 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol39/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 07 EARL .DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/16/17 4:45 PM Legacies of the Nuremberg SS- Einsatzgruppen Trial after 70 Years HILARY EARL* I. INTRODUCTION War crimes trials are almost commonplace today as the normal course of events that follow modern-day wars and atrocities. In the North Atlantic, we use the liberal legal tradition to redress the harm caused to civilians by the state and its agents during periods of State and inter-State conflict. The truth is, war crimes trials are a recent invention. There were so-called war crimes trials after World War I, but they were not prosecuted with any real conviction or political will. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Financial Sanctions Notice 21/01/2021 Democratic Republic of the Congo Introduction 1. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (S.I. 2019/433) were made under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (the Sanctions Act) and provide for the freezing of funds and economic resources of certain persons, entities or bodies which are, or have been, involved in the commission of a serious human rights violation or abuse in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a violation of international humanitarian law in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or obstructing or undermining respect for democracy, the rule of law and good governance. 2. This notice is to issue a correction for 6 listings in the Democratic Republic of the Congo regime. This amendment brings the Consolidated List entries into line with the Regulation. Notice summary 3. The following entries have been amended and are still subject to an asset freeze: • Gaston IYAMUREMYE (Group ID: 11275) • Sylvestre MUDACUMURA (Group ID: 8714) • Leopold MUJYAMBERE (Group ID: 10679) • Jamil MUKULU (Group ID: 12204) • Laurent NKUNDA (Group ID: 8710) • Bosco TAGANDA (Group ID: 8736) 1 What you must do 4. You must: i. check whether you maintain any accounts or hold any funds or economic resources for the persons set out in the Annex to this Notice; ii. freeze such accounts, and other funds or economic resources and any funds which are owned or controlled by persons set out in the Annex to the Notice iii. refrain from dealing with the funds or assets or making them available (directly or indirectly) to such persons unless licensed by the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI); iv. -

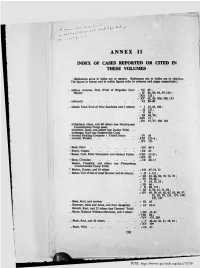

Annex Ii Index of Cases Reported Or Cited in These Volumes

J» ■ i, J L-, UJ> O'- ' / C , " i ANNEX II INDEX OF CASES REPORTED OR CITED IN THESE VOLUMES (References given in italics arc to reports. References not in italics are to citations. The figures in roman and in arabic figures refer to volumes and pages respectively.) Abbaye Ardcnnc Trial (Trial of Brigadier Kurt~ 111 6 9 ; Meyer). ✓ IV 85, 89, 997-110 5 , ; *X1I 123: ✓ X V 62, ¿4, 106,109, 133 - Ahlbrecht ......................................................... X I 89-90 « Almelo Trial (Trial or Otto Sandrock and 3 others)✓ / 35-45,1 0 6 ; ✓ 11 127; w V 1 0 ; . XI 46,50; . X IV 15 ; * X V 47, 97, 108, 184 Allfuldisch, Hans, and 60 others (sec Mauthausen Concentration Camp case). Altstötter, Josef, and others (sec Justkc Trial) .. Ambcrgcr, Karl (sec Dreierwalde Case) - Armour Packing Company v. United States .. s W 54 - Awochi, Washio ..............................................^Xlll 122-4 ; X V 121 » Back, P e t e r ........................................................ ✓/// 60-1 x Bauer, August ..............................................«'IX 65 v Bauer, Carl, Ernst Schramcck and Herbert Falten*Vlll 15-21; v X V 82 v'Baus, Christian ..............................................s l X 68-71 Becker, Friedrich, and others (sec Flossenberg Concentration Camp Trial) t'Becker, Gustav, and 19 others ........................ JVU 67-73,15 ✓ Belsen Trial (Trial of Josef Kramer and 44 others)..11 1-152;✓ ✓ III 6 3 ,6 6 ,6 9 .7 0 ,7 2 ,7 4 ; ✓ IV 79,86 ; ✓ V 14, 15, 23 ; ✓ IX 66 ; ✓ X 68, 173 ; ✓ XI 9,10,11,71,83; ✓ X V 45, 59, 61, 65, 67, 83, 86, 87, 92, 93, 97, 121. -

Belsen, Dachau, 1945: Newspapers and the First Draft of History

Belsen, Dachau, 1945: Newspapers and the First Draft of History by Sarah Coates BA (Hons.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University March 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the opportunities Deakin University has provided me over the past eight years; not least the opportunity to undertake my Ph.D. Travel grants were especially integral to my research and assistance through a scholarship was also greatly appreciated. The Deakin University administrative staff and specifically the Higher Degree by Research staff provided essential support during my candidacy. I also wish to acknowledge the Library staff, especially Marion Churkovich and Lorraine Driscoll and the interlibrary loans department, and sincerely thank Dr Murray Noonan for copy-editing this thesis. The collections accessed as part of an International Justice Research fellowship undertaken in 2014 at the Thomas J Dodd Centre made a positive contribution to my archival research. I would like to thank Lisa Laplante, interim director of the Dodd Research Center, for overseeing my stay at the University of Connecticut and Graham Stinnett, Curator of Human Rights Collections, for help in accessing the Dodd Papers. I also would like to acknowledge the staff at the Bergen-Belsen Gedenkstätte and Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial who assisted me during research visits. My heartfelt gratitude is offered to those who helped me in various ways during overseas travel. Rick Gretsch welcomed me on my first day in New York and put a first-time traveller at ease. Patty Foley’s hospitality and warmth made my stay in Connecticut so very memorable. -

Effizienz Und Mord: Das Kz System 1943 1945

98 | 99 EFFIZIENZ UND MORD: DAS KZ&SYSTEM 1943&1945 Stefan Hördler Ende Dezember 1943 sandte der SS-Hygieniker und Funktionskader desertierten, Wehrmacht, Polizei, SS-Sturmbannführer Karl Groß seine Vorschläge Feuerwehr, Volkssturm, Parteifunktionäre, SA, für eine eDzientere Organisation des Lagerbetrie- Reichsarbeitsdienst und Hitlerjugend sollten KZ- bes an den Amtschef D III (Sanitätswesen des KZ- HäNlinge beaufsichtigen und massakrierten nicht Systems) im SS-WirtschaNs-Verwaltungshaupt- selten – teils unter Beteiligung der ZiVilbeVölke- amt (SS-WVHA): „Um eine unnötige Belastung rung – aus Furcht oder aus niederen Beweggrün- des Betriebes mit körperlich mangelhaNem Men- den angeblich lästige, gefährliche, erschöpNe oder schenmaterial und eine dadurch bedingte Anhäu- flüchtende Gefangene. In summa bedeutete diese fung Von [A]rbeitsunfähigen zu Vermeiden, wäre Phase eine Aufgabe Vertrauter Machtstrukturen, eine entsprechend strenge Auswahl der HäNlinge gesicherter Machträume und eingeübter Hand- (ärztliche Musterung) Vor Arbeitseinstellung un- lungs- und Tagesabläufe. Die „Todesmärsche“ führ- bedingt zu empfehlen“. Weiter heißt es, dass „schon ten die bis dahin gültigen räumlichen und zeitli- jetzt an die Errichtung eines Ausweichlagers für chen Regeln ad absurdum. 2 arbeitsunfähige HäNlinge zu denken [sei], da deren Anzahl ständig steigen wird.“ Nicht zuletzt sei der Bau eines Krematoriums zu beschleunigen. „Hier- DAS KZ&SYSTEM IN DER ZWEITEN bei ist sofort an ausreichenden Verbrennungsraum KRIEGSHÄLFTE zu denken.“ 1 Was Groß nach seiner Visite des Buchenwal- Neben mehreren Zehntausend ungleich großen der Außenlagers Dora als menschenVerachtende sogenannten Arbeitserziehungslagern, Jugend- Handlungsanleitung für die reibungslose Auf- schutzlagern, Zigeunerlagern, Kriegsgefangenen- rechterhaltung des Lagerbetriebes formulierte, lagern, Zwangsarbeitslagern, Durchgangslagern, sollte 1944 zu einer Maxime für die Rationalisie- Ghettos und anderen HaNstätten stellten die Lager rung des gesamten KZ-Systems werden.