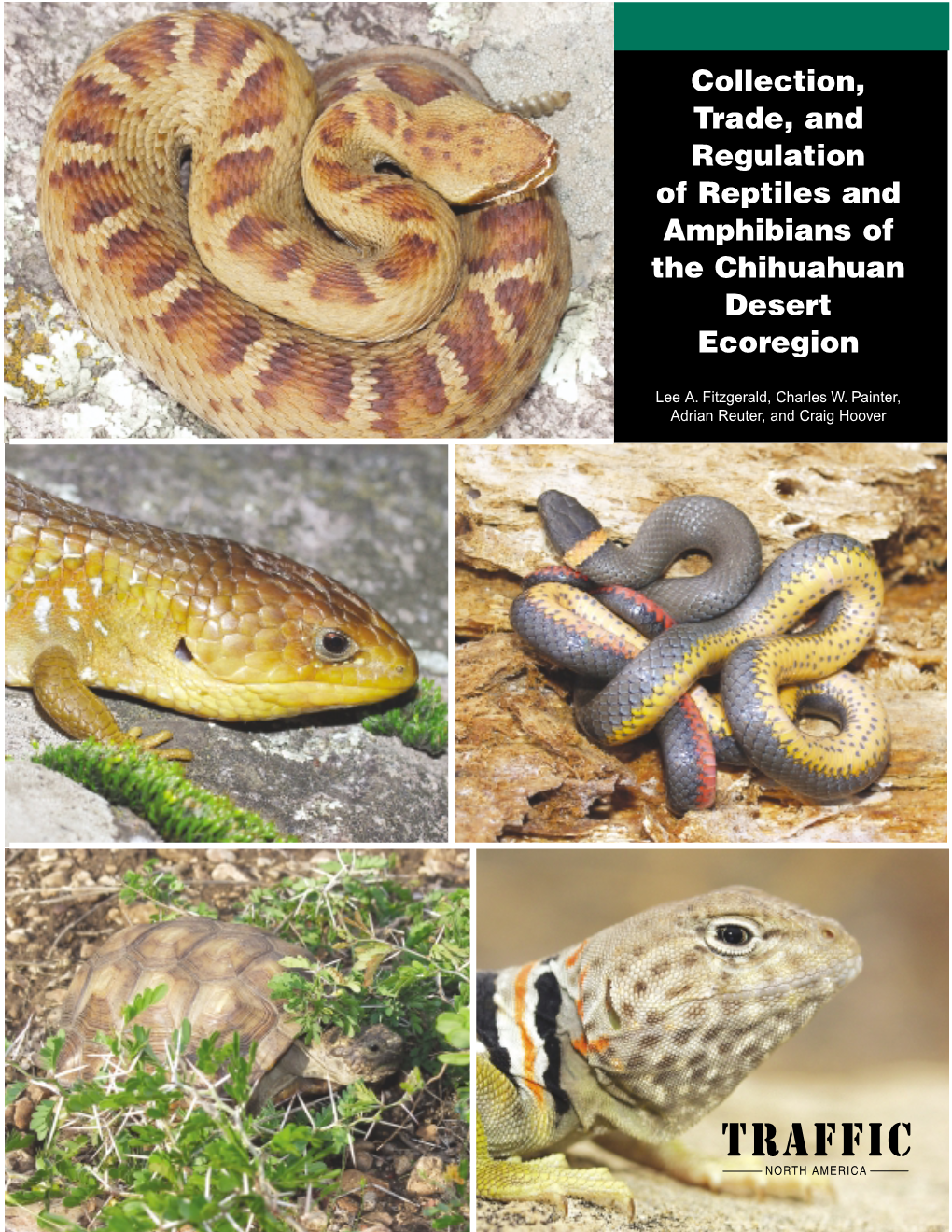

Collection, Trade & Regulation of Reptiles & Amphibians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS by ZOO ATLANTA STAFF 1978–Present

RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS BY ZOO ATLANTA STAFF 1978–Present This listing may be incomplete, and some citation information may be incomplete or inaccurate. Please advise us if you are aware of any additional publications. Copies of publications may be available directly from the authors, or from websites such as ResearchGate. Zoo Atlanta does not distribute copies of articles on behalf of these authors. Updated: 22 Jan 2020 1978 1. Maple, T.L., and E.L. Zucker. 1978. Ethological studies of play behavior in captive great apes. In E.O. Smith (Ed.), Social Play in Primates. New York: Academic Press, 113–142. 1979 2. Maple, T.L. 1979. Great apes in captivity: the good, the bad, and the ugly. In J. Erwin, T.L. Maple, G. Mitchell (Eds.), Captivity and Behavior: Primates in Breeding Colonies, Laboratories and Zoos. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 239–272. 3. Strier, K.B., J. Altman, D. Brockman, A. Bronikowski, M. Cords, L. Fedigan, H. Lapp, J. Erwin, T.L. Maple, and G. Mitchell (Eds.). 1979. Captivity and Behavior: Primates in Breeding Colonies, Laboratories and Zoos. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 286. 1981 4. Hoff, M.P., R.D. Nadler, and T.L. Maple. 1981. Development of infant independence in a captive group of lowland gorillas. Developmental Psychobiology 14:251–265. 5. Hoff, M.P., R.D. Nadler, and T.L. Maple. 1981. The development of infant play in a captive group of lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). American Journal of Primatology 1:65–72. 1982 6. Hoff, M.P., R.D. Nadler, and T.L. Maple. -

Herpetological Information Service No

Type Descriptions and Type Publications OF HoBART M. Smith, 1933 through June 1999 Ernest A. Liner Houma, Louisiana smithsonian herpetological information service no. 127 2000 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. Introduction Hobart M. Smith is one of herpetology's most prolific autiiors. As of 30 June 1999, he authored or co-authored 1367 publications covering a range of scholarly and popular papers dealing with such diverse subjects as taxonomy, life history, geographical distribution, checklists, nomenclatural problems, bibliographies, herpetological coins, anatomy, comparative anatomy textbooks, pet books, book reviews, abstracts, encyclopedia entries, prefaces and forwords as well as updating volumes being repnnted. The checklists of the herpetofauna of Mexico authored with Dr. Edward H. Taylor are legendary as is the Synopsis of the Herpetofalhva of Mexico coauthored with his late wife, Rozella B. -

Checklist of Helminths from Lizards and Amphisbaenians (Reptilia, Squamata) of South America Ticle R A

The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases ISSN 1678-9199 | 2010 | volume 16 | issue 4 | pages 543-572 Checklist of helminths from lizards and amphisbaenians (Reptilia, Squamata) of South America TICLE R A Ávila RW (1), Silva RJ (1) EVIEW R (1) Department of Parasitology, Botucatu Biosciences Institute, São Paulo State University (UNESP – Univ Estadual Paulista), Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil. Abstract: A comprehensive and up to date summary of the literature on the helminth parasites of lizards and amphisbaenians from South America is herein presented. One-hundred eighteen lizard species from twelve countries were reported in the literature harboring a total of 155 helminth species, being none acanthocephalans, 15 cestodes, 20 trematodes and 111 nematodes. Of these, one record was from Chile and French Guiana, three from Colombia, three from Uruguay, eight from Bolivia, nine from Surinam, 13 from Paraguay, 12 from Venezuela, 27 from Ecuador, 17 from Argentina, 39 from Peru and 103 from Brazil. The present list provides host, geographical distribution (with the respective biome, when possible), site of infection and references from the parasites. A systematic parasite-host list is also provided. Key words: Cestoda, Nematoda, Trematoda, Squamata, neotropical. INTRODUCTION The present checklist summarizes the diversity of helminths from lizards and amphisbaenians Parasitological studies on helminths that of South America, providing a host-parasite list infect squamates (particularly lizards) in South with localities and biomes. America had recent increased in the past few years, with many new records of hosts and/or STUDIED REGIONS localities and description of several new species (1-3). -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

Intrageneric Relationships Among Colubrid Snakes of the Genus Geophis Wagler

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 131 Intrageneric Relationships Among Colubrid Snakes of the Genus Geophis Wagler BY FLOYD LESLIE DOWNS College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio ANN ARBOR MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN JULY 26, 1967 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies bascd principally upon the collections in the Museum. Thcy are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and indi- viduals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum techniques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separtely. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan. LISTOF MISCELLANEOUSPUBLICATIONS ON REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS No. The amphibians and reptiles of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colom- bia. By ALEXANDERG. RUTHVEN.(1922) 69 pp., 12 pls., 2 figs., 1 map .. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Herpetology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1993 Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A. Somma Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Somma, Louis A., "Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska?" (1993). Papers in Herpetology. 11. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Herpetology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. @ o /' number , ,... :S:' .' ,. '. 1'1'13 Do Mono Li ••rel,. Occur ill 1!I! ..br .... l< .. ? by Louis A. Somma Department of- Zoology University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Amphisbaenids, or worm lizards, are a small enigmatic suborder of reptiles (containing 4 families; ca. 140 species) within the order Squamata, which include~ the more speciose lizards and snakes (Gans 1986). The name amphisbaenia is derived from the mythical Amphisbaena (Topsell 1608; Aldrovandi 1640), a two-headed beast (one head at each end), whose fantastical description may have been based, in part, upon actual observations of living worm lizards (Druce 1910). While most are limbless and worm-like in appearance, members of the family Bipedidae (containing the single genus Sipes) have two forelimbs located close to the head. This trait, and the lack of well-developed eyes, makes them look like two-legged worms. -

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 60, Number 1, Pp

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, volume 60, number 1, pp. 190–201 doi:10.1093/icb/icaa015 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology SYMPOSIUM Convergent Evolution of Elongate Forms in Craniates and of Locomotion in Elongate Squamate Reptiles Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-abstract/60/1/190/5813730 by Clark University user on 24 July 2020 Philip J. Bergmann ,* Sara D. W. Mann,* Gen Morinaga,1,*,† Elyse S. Freitas‡ and Cameron D. Siler‡ *Department of Biology, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA; †Department of Integrative Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA; ‡Department of Biology and Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA From the symposium “Long Limbless Locomotors: The Mechanics and Biology of Elongate, Limbless Vertebrate Locomotion” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology January 3–7, 2020 at Austin, Texas. 1E-mail: [email protected] Synopsis Elongate, snake- or eel-like, body forms have evolved convergently many times in most major lineages of vertebrates. Despite studies of various clades with elongate species, we still lack an understanding of their evolutionary dynamics and distribution on the vertebrate tree of life. We also do not know whether this convergence in body form coincides with convergence at other biological levels. Here, we present the first craniate-wide analysis of how many times elongate body forms have evolved, as well as rates of its evolution and reversion to a non-elongate form. We then focus on five convergently elongate squamate species and test if they converged in vertebral number and shape, as well as their locomotor performance and kinematics. -

Evolution of the Iguanine Lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) As Determined by Osteological and Myological Characters David F

Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series Volume 12 | Number 3 Article 1 1-1971 Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters David F. Avery Department of Biology, Southern Connecticut State College, New Haven, Connecticut Wilmer W. Tanner Department of Zoology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byuscib Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Avery, David F. and Tanner, Wilmer W. (1971) "Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters," Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series: Vol. 12 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byuscib/vol12/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. S-^' Brigham Young University f?!AR12j97d Science Bulletin \ EVOLUTION OF THE IGUANINE LIZARDS (SAURIA, IGUANIDAE) AS DETERMINED BY OSTEOLOGICAL AND MYOLOGICAL CHARACTERS by David F. Avery and Wilmer W. Tanner BIOLOGICAL SERIES — VOLUME Xil, NUMBER 3 JANUARY 1971 Brigham Young University Science Bulletin -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. | http://redlist-ARC.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma De Puebla

BENEMÉRITA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE PUEBLA ESCUELA DE BIOLOGÍA ZONAS PRIORITARIAS DE CONSERVACION BIOLOGICA A PARTIR DEL ANÁLISIS ESPACIAL DE LA HERPETOFAUNA DE LOS ESTADOS DE PUEBLA Y TLAXCALA Tesis que para obtener el título de BIÓLOGO (A) . PRESENTA: GRISELDA OFELIA JORGE LARA TUTOR: DR. RODRIGO MACIP RÍOS NOVIEMBRE 2013 1 AGRADECIMIENTOS A los proyectos Estado de conservación de los recursos naturales y la biodiversidad de los estados de puebla y Tlaxcala. PROMEP/103.5/12/4367 Proyecto: BUAP-PTC-316 y Estado actual de Conservación de la Biodiversidad de Puebla. Proyecto VIEP modalidad: consolidación de investigadores jóvenes, por el apoyo económico brindado para la ejecución de esta tesis. Al Instituto de Instituto de Ciencias de Gobierno y Desarrollo Estratégico por abrirme sus puertas en todo el desarrollo de mi tesis. Al Dr. Rodrigo Macip por sus enseñanzas, su apoyo y su paciencia para la realización de esta investigación. A mis sinodales por la disponibilidad para la revisión del manuscrito y las pertinentes correcciones del mismo. Al M. en C. J. Silvestre Toxtle Tlamaní por su disponibilidad para atender mis dudas tanto de la tesis y en los últimos cuatrimestres de la carrera. Al Dr. Flores Villela y la Ma. en C. Guadalupe Gutiérrez Mayen por haberme facilitado literatura importante para el desarrollo de esta tesis. A Sami por dedicarme su tiempo su paciencia y nunca dejarme vencer, gracias por ser parte de mi vida. A mis amigas de la Universidad Paty Téllez, Vere Cruz, Elo Cordero, las gemelas Annya y Georgia, Azarel, Adris de Psicología, Sus Escobar que siempre estuvieron conmigo durante la carrera y apoyándome en mi tesis y a Karina y Misael que me hicieron pasar momentos muy agradables en el laboratorio de SIG.