Vol-108-No-4-View-The-Full-Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania's Connection to Slavery

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania’s Connection to Slavery Clay Scott Graubard The University of Pennsylvania, Class of 2019 April 19, 2018 © 2018 CLAY SCOTT GRAUBARD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 OVERVIEW 3 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION 4 PRIMER ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 5 EBENEZER KINNERSLEY (1711 – 1778) 7 ROBERT SMITH (1722 – 1777) 9 THOMAS LEECH (1685 – 1762) 11 BENJAMIN LOXLEY (1720 – 1801) 13 JOHN COATS (FL. 1719) 13 OTHERS 13 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION CONCLUSION 15 FINANCIAL ASPECTS 17 WEST INDIES FUNDRAISING 18 SOUTH CAROLINA FUNDRAISING 25 TRUSTEES OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 31 WILLIAM ALLEN (1704 – 1780) AND JOSEPH TURNER (1701 – 1783): FOUNDERS AND TRUSTEES 31 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (1706 – 1790): FOUNDER, PRESIDENT, AND TRUSTEE 32 EDWARD SHIPPEN (1729 – 1806): TREASURER OF THE TRUSTEES AND TRUSTEE 33 BENJAMIN CHEW SR. (1722 – 1810): TRUSTEE 34 WILLIAM SHIPPEN (1712 – 1801): FOUNDER AND TRUSTEE 35 JAMES TILGHMAN (1716 – 1793): TRUSTEE 35 NOTE REGARDING THE TRUSTEES 36 FINANCIAL ASPECTS CONCLUSION 37 CONCLUSION 39 THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 40 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 42 BIBLIOGRAPHY 43 DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 2 INTRODUCTION DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 3 Overview The goal of this paper is to present the facts regarding the University of Pennsylvania’s (then the College and Academy of Philadelphia) significant connections to slavery and the slave trade. The first section of the paper will cover the construction and operation of the College and Academy in the early years. As slavery was integral to the economy of British North America, to fully understand the University’s connection to slavery the second section will cover the financial aspects of the College and Academy, its Trustees, and its fundraising. -

Old Bacon Face

The Judge’s Lawyer In successfully defending the ate tries him or her, with a two-thirds vote irascible Supreme Court Justice needed to convict—has run its full course only 18 times. Three of the 18 have been Samuel Chase—aka “Old Bacon especially momentous cases: those of two Face”—against impeachment, presidents, Andrew Johnson (1868) and Joseph Hopkinson C1786 G1789 William Jefferson Clinton (1998-99), and that of a Supreme Court justice, Samuel helped set a high bar for removal Chase (1805). from office and establish the Graduates of the University of Pennsyl- principle of judicial independence. vania have figured in two of those three blockbusters. The Clinton impeachment By Dennis Drabelle featured Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter C’51 breaking ranks with most of his Republican colleagues to vote against of this writing (February 9, 2018), conviction. Important as the fate of a Samuel Chase the Impeach-O-Meter—Slate particular president may be, however, magazine’s self-styled “wildly Perhaps the most remarkable thing even more was at stake in the Chase case: As subjective and speculative daily about impeachment is how seldom it the separation of powers. The phalanx of estimate” of the likelihood that Presi- happens. Common sense and the law of attorneys representing the embattled dent Donald Trump W’68 won’t get to averages suggest that hundreds of federal jurist included Joseph Hopkinson C1786 serve out his term—stands at 45 per- officials have abused their power or G1789, to whom was entrusted a crucial cent. That’s actually a pretty good num- betrayed the public’s trust over the years. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

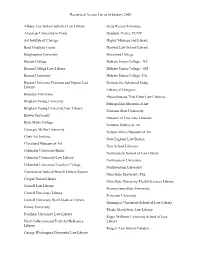

Reciprocal Access List As of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer

Reciprocal Access List as of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer Law Library Getty Research Institute American University in Cairo Graduate Center, CUNY Art Institute of Chicago Hagley Museum and Library Bard Graduate Center Harvard Law School Library Binghamton University Haverford College Boston College Hebrew Union College - NY Boston College Law Library Hebrew Union College - OH Boston University Hebrew Union College -CA Boston University Fineman and Pappas Law Institute for Advanced Study Library Library of Congress Brandeis University Massachusetts Trial Court Law Libraries Brigham Young University Metropolitan Museum of Art Brigham Young University Law Library Montana State University Brown University Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Bryn Mawr College National Gallery of Art Carnegie Mellon University Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Clark Art Institute New England Law Boston Cleveland Museum of Art New School Libraries Columbia University-Butler Northeastern School of Law Library Columbia University-Law Library Northeastern University Columbia University-Teachers College Northwestern University Connecticut Judicial Branch Library System Ohio State University, The Cooper Union Library Ohio State University-Health Sciences Library Cornell Law Library Pennsylvania State University Cornell University Library Princeton University Cornell University Weill Medical Library Quinnipiac University School of Law Library Emory University Rhode Island State Law Library Fordham University Law Library Roger Williams University School of Law Frick -

If Rumors Were Horses Ensuring Access to Government Information

c/o Katina Strauch Post Office Box 799 Sullivan’s Island, SC 29482 ALA MIDWINTER ISSUE TM VOLUME 29, NUMBER 6 DECEMBER 2017 - JANUARY 2018 ISSN: 1043-2094 “Linking Publishers, Vendors and Librarians” Ensuring Access to Government Information by Shari Laster (Head, Open Stack Collections, Arizona State University) <[email protected]> and Lynda Kellam (Social Science Data Librarian, University of North Carolina at Greensboro) <[email protected]> n the United States, the dominant paradigm collect, describe, and preserve federal govern- that connect a specialized group of publishers of research libraries as content managers ment information in print and digital formats, — government agencies — with libraries as Ifor print government documents and access much of it in partnership with the U.S. Gov- content stewards. Libraries are collaborating portals for digital government information ernment Publishing Office (GPO) and other with partners to explore new methods and ap- and data took a substantial turn in late government agencies, received renewed proaches to solving a persistent problem: how 2016. With the change in Presidential attention, even as new energy poured can we ensure that government information administration, academics, journalists, into experimental and transformative will be freely available to the public for the and other constituencies whose work models for capturing digital content at foreseeable future? relies on uninterrupted access to federal risk for loss from trusted public sources. The Federal Depository Library Pro- information expressed concern about News outlets featured and valorized gram (FDLP) continues important work that the specter of political threats to the work of library and information is now over two centuries old. -

The Writing of American Library History, 1876- 1976

The Writing of American Library History, 1876- 1976 JOHN CALVIN COLSOIV THEOTHER ARTICLES in this issue of Library Trends are concerned with substantive elements of American librarianship, 1876 to 1976; this article examines the ways in which some American librarians and others have viewed the progress of American librari- anship during the same century. Inevitably, it is also about the ways in which that development has not been viewed, if only by implication, for, as a study of the literature will indicate, much of American librarianship during the past century has been left unexamined by the historians of American libraries. A general view of the course of development may be gained from these eighteen papers, but many of the details will not be clear. There are simply too many gaps in the study of the record of American librarianship. Causes for this state of affairs there may be, but the purpose behind these remarks is not to fix blame for them. Kather, it is to examine some of the assumptions about, and to assess some of the results of, the historical study of American librarianship.’ Thirty years ago, the Library Quarterly published Jesse Shera’s milestone paper, “The Literature of American Library History.”2The present paper is a study of the history of American libraries and librarianship since then, with some consideration of the period 1930- 45. Approximately two-thirds of Shera’s paper was a rather bleak review of what passed for the history of American librarianship in the years 1850-1930. Indeed, Shera was not given to praise of most works from 1930 to 1945, but he was hopeful for the future, in light of the works of Carleton Joeckel,s Gwladys S~encer,~and Sidney Ditzi0n.j In these and one or two other works, Shera saw the arrival of the “new John Calvin Colson is Assistant Professor of Library Science, Northern Illinois Uni- versity, Dekalb. -

Washington Resigning His Commission

About the Artwork: Washington Resigning His Commission In 1835 a movement was started in Philadelphia to erect a statue of George Washington in Washington Square. The foundation for the monument was laid but soon, the project began to languish. By 1840 there was enough money in the fund to resume plans for the monument’s execution, German artist Ferdinand Pettrich was the favored sculptor. On July 2, 1840, at a meeting of citizens of Philadelphia, a series of resolutions was adopted, one of which stated: “Resolved, that this meeting having been furnished with the best testimonials of the skill and classical taste of Ferdinand Pettrich, pupil of Thorvaldsen, that he be requested, at the earliest period, to furnish this committee a model of the statue upon a pedestal of proportionate dimensions, containing appropriate bas relief representations in full costume of the continental army of the revolution.” Sometime in August of 1840, an announcement was made that permission had been obtained from the Council of the City to exhibit the model of the Washington statue in Independence Hall, and that it would be on view there from August 18 until September 1. A description of the work was written in the August 29, 1840 issue of the Saturday Evening Post: “Statue of Washington. The model exhibited during the last week to large crowds in the Hall of Independence is one eighth of the full dimensions when completed. The bas reliefs on the four panels represent figures which are to be the size of life. The basement and sub-basement are to be composed of New England granite to the height of fourteen feet, and executed in imitation of rock work. -

6.3 Law Libraries and Legal Material

materials and equipment. 6.3 Law Libraries and 3. **When requested and where resources Legal Material permit, facilities shall provide detainees meaningful access to law libraries, legal I. Purpose and Scope materials and related materials on a regular This detention standard protects detainees’ rights by schedule and no less than 15 hours per week. ensuring their access to courts, counsel and 4. Special scheduling consideration shall be comprehensive legal materials. given to detainees facing deadlines or time This detention standard applies to the following constraints. types of facilities housing ICE/ERO detainees: 5. Detainees shall not be required to forgo recreation time to use the law library. Requests • Service Processing Centers (SPCs); for additional time to use the law library shall be • Contract Detention Facilities (CDFs); and accommodated to the extent possible, including accommodating work schedules when • State or local government facilities used by practicable, consistent with the orderly and secure ERO through Intergovernmental Service operation of the facility. Agreements (IGSAs) to hold detainees for more than 72 hours. 6. Detainees shall have access to courts and counsel. Procedures in italics are specifically required for 7. Detainees shall be able to have confidential SPCs, CDFs, and Dedicated IGSA facilities. Non- contact with attorneys and their authorized dedicated IGSA facilities must conform to these representatives in person, on the telephone and procedures or adopt, adapt or establish alternatives, through correspondence. provided they meet or exceed the intent represented 8. Detainees shall receive assistance where needed by these procedures. (e.g., orientation to written or electronic media For all types of facilities, procedures that appear in and materials; assistance in accessing related italics with a marked (**) on the page indicate programs, forms and materials); in addition, optimum levels of compliance for this standard. -

History of the Arkansas Supreme Court Library

The Supreme Court Library -- A Source of Pride By JACQUELINE S. WRIGHT Librarian Reprinted from 47 Arkansas Historical Quarterly 136 (Summer 1988) with permission of the Arkansas Historical Association. THE ARKANSAS SUPREME COURT LIBRARY, founded by act of the general assembly in 1851, is the oldest library in the state of Arkansas that is still operating. It serves judges, lawyers and laypersons who research in the very same books that were acquired over one hundred years ago. That is not to say that the library has not developed and grown - it has. New books are added every day, as well as new formats for information, such as microforms and computers. But the nucleus of the collection that was acquired in the last century is still here. State reports, session laws, seventeenth and eighteenth century treatises authored by Sir Edward Coke and Sir William Blackstone and their contemporaries are useful today because they contain solutions to problems that are based on logic and equity. It is difficult to imagine any controversy that might surround such a useful institution. However, some peculiar language in the legislation indicates that there was disagreement about something to do with the library. But the newspapers published in the 1850s hardly mention either its need or its founding. History books mention its founding but cast no light on the circumstances surrounding this event. The search for information about these circumstances was interesting. It required several forays into the files of the Arkansas History Commission, the Special Arkansas Collection at the Library of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and the Old State House Library and Archives. -

Pennsylvania History

Pennsylvania History a journal of mid-atlantic studies PHvolume 80, number 2 · spring 2013 “Under These Classic Shades Together”: Intimate Male Friendships at the Antebellum College of New Jersey Thomas J. Balcerski 169 Pennsylvania’s Revolutionary Militia Law: The Statute that Transformed the State Francis S. Fox 204 “Long in the Hand and Altogether Fruitless”: The Pennsylvania Salt Works and Salt-Making on the New Jersey Shore during the American Revolution Michael S. Adelberg 215 “A Genuine Republican”: Benjamin Franklin Bache’s Remarks (1797), the Federalists, and Republican Civic Humanism Arthur Scherr 243 Obituaries Ira V. Brown (1922–2012) Robert V. Brown and John B. Frantz 299 Gerald G. (Gerry) Eggert (1926–2012) William Pencak 302 bOOk reviews James Rice. Tales from a Revolution: Bacon’s Rebellion and the Transformation of Colonial America Reviewed by Matthew Kruer 305 This content downloaded from 128.118.153.205 on Mon, 15 Apr 2019 13:08:47 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Sally McMurry and Nancy Van Dolsen, eds. Architecture and Landscape of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1720-1920 Reviewed by Jason R. Sellers 307 Patrick M. Erben. A Harmony of the Spirits: Translation and the Language of Community in Early Pennsylvania Reviewed by Karen Guenther 310 Jennifer Hull Dorsey. Hirelings: African American Workers and Free Labor in Early Maryland Reviewed by Ted M. Sickler 313 Kenneth E. Marshall. Manhood Enslaved: Bondmen in Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century New Jersey Reviewed by Thomas J. Balcerski 315 Jeremy Engels. Enemyship: Democracy and Counter-Revolution in the Early Republic Reviewed by Emma Stapely 318 George E. -

Illuminating the Past

Published by PhotoBook Press 2836 Lyndale Ave. S. Minneapolis, MN 55408 Designed at the School of Information and Library Science University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 216 Lenoir Drive CB#3360, 100 Manning Hall Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3360 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is committed to equality of educational opportunity. The University does not discriminate in o fering access to its educational programs and activities on the basis of age, gender, race, color, national origin, religion, creed, disability, veteran’s status or sexual orientation. The Dean of Students (01 Steele Building, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-5100 or 919.966.4042) has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the University’s non-discrimination policies. © 2007 Illuminating the Past A history of the first 75 years of the University of North Carolina’s School of Information and Library Science Illuminating the past, imagining the future! Dear Friends, Welcome to this beautiful memory book for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Information and Library Science (SILS). As part of our commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the founding of the School, the words and photographs in these pages will give you engaging views of the rich history we share. These are memories that do indeed illuminate our past and chal- lenge us to imagine a vital and innovative future. In the 1930’s when SILS began, the United States had fallen from being the land of opportunity to a country focused on eco- nomic survival. The income of the average American family had fallen by 40%, unemployment was at 25% and it was a perilous time for public education, with most communities struggling to afford teachers and textbooks for their children. -

2018 Annual Report

2018 Annual Report e Wisconsin State Law Library exists to serve the legal information needs of the o cers and employees of this state, attorneys and the public by providing the highest quality of professional expertise in the selection, maintenance and use of materials, information and technology in order to facilitate equal access to the law. Wisconsin State Law Library wilawlibrary.gov Welcome to the Library I’m pleased to share our inaugural annual report. The library of 2018 is different in many ways from the library of 1836 however, what has not changed is our commitment to providing legal information. We are proud to serve the Wisconsin Court System, executive, and legislative branches of State government. In addition, we serve federal, county, city, and town government users. Attorneys, legal professionals, librar- ians, business owners, landlords and tenants, and non-profi t organiza- tions all are welcome to use the resources available at our three librar- ies. Our libraries welcome self-represented individuals, members of the public, and students to use our libraries as well. If you are looking for legal information or have a question about a legal matter we are ready to help you. We are your State Law Library. Locations David T. Prosser Jr. State Law Milwaukee County Law Library Dane County Law Library Library Courthouse Courthouse 120 Martin Luther King Jr Blvd Room G8 215 S Hamilton St Madison WI 53703 901 North 9th St Room L1007 Milwaukee WI 53233-1425 Madison WI 53703 8-5 Monday-Friday 8-4:30 Monday-Friday 8:30-4:30 Monday-Friday Staff in 2018 David T.