History of the Arkansas Supreme Court Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policing the Self-Help Legal Market: Consumer Protection Or Protection of the Legal Cartel?

POLICING THE SELF-HELP LEGAL MARKET: CONSUMER PROTECTION OR PROTECTION OF THE LEGAL CARTEL? JULEE C. FISCHER* INTRODUCTION The emergence of information technology in the legal field is spearheading new approaches to the practice of law, but the legal community is questioning whether the new technology may be a double-edged sword. The Information Revolution is reshaping traditional lawyer functions, forcing innovations in everything from research and document management to marketing and client communications. Yet, just as technology drives change inside law firms, consumers too are seizing the knowledge that is increasingly at their fingertips. The market is flourishing for self-help legal counsel. An increasing array of Internet Web sites often dispense legal advice and information free of charge. This advice ranges from estate planning and contract issues to custody battles and torts. Further, the legal industry is witness to the advent of do-it-yourself legal software packages marketed directly to consumers. Innovative? Yes. Easier? Certainly. But to what extent is this a blessing or a curse, both to lawyers and consumers?1 Self-help law can be defined as “any activity by a person in pursuit of a legal goal or the completion of a legal task that [does not] involve legal advice or representation by a lawyer.”2 Consumers participating in the self-help market are typically driven by factors such as relative cost, self-reliance, necessity, and distrust of lawyers.3 Clearly, such products offer the public up-front benefits of convenience and availability. Nevertheless, larger issues arise concerning who is responsible for the advice and whether it is dispensed by lawyers. -

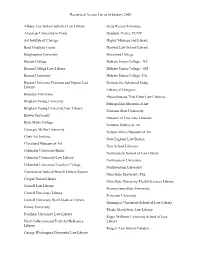

Reciprocal Access List As of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer

Reciprocal Access List as of January 2020 Albany Law School Schaffer Law Library Getty Research Institute American University in Cairo Graduate Center, CUNY Art Institute of Chicago Hagley Museum and Library Bard Graduate Center Harvard Law School Library Binghamton University Haverford College Boston College Hebrew Union College - NY Boston College Law Library Hebrew Union College - OH Boston University Hebrew Union College -CA Boston University Fineman and Pappas Law Institute for Advanced Study Library Library of Congress Brandeis University Massachusetts Trial Court Law Libraries Brigham Young University Metropolitan Museum of Art Brigham Young University Law Library Montana State University Brown University Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Bryn Mawr College National Gallery of Art Carnegie Mellon University Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Clark Art Institute New England Law Boston Cleveland Museum of Art New School Libraries Columbia University-Butler Northeastern School of Law Library Columbia University-Law Library Northeastern University Columbia University-Teachers College Northwestern University Connecticut Judicial Branch Library System Ohio State University, The Cooper Union Library Ohio State University-Health Sciences Library Cornell Law Library Pennsylvania State University Cornell University Library Princeton University Cornell University Weill Medical Library Quinnipiac University School of Law Library Emory University Rhode Island State Law Library Fordham University Law Library Roger Williams University School of Law Frick -

6.3 Law Libraries and Legal Material

materials and equipment. 6.3 Law Libraries and 3. **When requested and where resources Legal Material permit, facilities shall provide detainees meaningful access to law libraries, legal I. Purpose and Scope materials and related materials on a regular This detention standard protects detainees’ rights by schedule and no less than 15 hours per week. ensuring their access to courts, counsel and 4. Special scheduling consideration shall be comprehensive legal materials. given to detainees facing deadlines or time This detention standard applies to the following constraints. types of facilities housing ICE/ERO detainees: 5. Detainees shall not be required to forgo recreation time to use the law library. Requests • Service Processing Centers (SPCs); for additional time to use the law library shall be • Contract Detention Facilities (CDFs); and accommodated to the extent possible, including accommodating work schedules when • State or local government facilities used by practicable, consistent with the orderly and secure ERO through Intergovernmental Service operation of the facility. Agreements (IGSAs) to hold detainees for more than 72 hours. 6. Detainees shall have access to courts and counsel. Procedures in italics are specifically required for 7. Detainees shall be able to have confidential SPCs, CDFs, and Dedicated IGSA facilities. Non- contact with attorneys and their authorized dedicated IGSA facilities must conform to these representatives in person, on the telephone and procedures or adopt, adapt or establish alternatives, through correspondence. provided they meet or exceed the intent represented 8. Detainees shall receive assistance where needed by these procedures. (e.g., orientation to written or electronic media For all types of facilities, procedures that appear in and materials; assistance in accessing related italics with a marked (**) on the page indicate programs, forms and materials); in addition, optimum levels of compliance for this standard. -

2018 Annual Report

2018 Annual Report e Wisconsin State Law Library exists to serve the legal information needs of the o cers and employees of this state, attorneys and the public by providing the highest quality of professional expertise in the selection, maintenance and use of materials, information and technology in order to facilitate equal access to the law. Wisconsin State Law Library wilawlibrary.gov Welcome to the Library I’m pleased to share our inaugural annual report. The library of 2018 is different in many ways from the library of 1836 however, what has not changed is our commitment to providing legal information. We are proud to serve the Wisconsin Court System, executive, and legislative branches of State government. In addition, we serve federal, county, city, and town government users. Attorneys, legal professionals, librar- ians, business owners, landlords and tenants, and non-profi t organiza- tions all are welcome to use the resources available at our three librar- ies. Our libraries welcome self-represented individuals, members of the public, and students to use our libraries as well. If you are looking for legal information or have a question about a legal matter we are ready to help you. We are your State Law Library. Locations David T. Prosser Jr. State Law Milwaukee County Law Library Dane County Law Library Library Courthouse Courthouse 120 Martin Luther King Jr Blvd Room G8 215 S Hamilton St Madison WI 53703 901 North 9th St Room L1007 Milwaukee WI 53233-1425 Madison WI 53703 8-5 Monday-Friday 8-4:30 Monday-Friday 8:30-4:30 Monday-Friday Staff in 2018 David T. -

Law Library Plans for the Print Materials Collection

LAW LIBRARY PLANS FOR THE PRINT MATERIALS COLLECTION ISBN 978-1-57440-353-4 ©2015 Primary Research Group Inc. Law Library Plans for the Print Materials Collection 2 | P a g e Law Library Plans for the Print Materials Collection Table of Contents THE QUESTIONNAIRE ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Characteristics of the Sample............................................................................................................................ 16 Use of Interlibrary Loan ................................................................................................................................. 17 Comfort Level with eBooks ........................................................................................................................... 17 Trends in Spending on Print, 2014, 2015, 2016 ............................................................................................ 17 Areas Subject to Most Aggressive Elimination of Print Titles ....................................................................... 17 Change in Size of the Print Collection over the Past Five Years .................................................................... 18 The Future of Print Collection over the Next Five years ............................................................................... 18 Percentage of Print Book Titles Culled Each Year ........................................................................................ -

The Arkansas Family Historian

The Arl(ansas Family Historian Volume 1, No.2, June 1962 THE ARKANSAS FAMILY HISTORIAN published by the ARKANSAS GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY Box 237 Fayetteville, Arkansas Vol.I No.2 w. J. LEMKE. editor June 1962 GREEl'Itns from G. R. Turrentine,Russellville President of the Arkansas Genealogical Society It was a pleasant surprise to learn that I have been elected presi dent of the Arkansas Genealogical Society. I do not knew if I have any qualifications for such a. job. It is true that.1 have been hunting ancestors for more than 20 years; but hunting for Turrentine ancestors is fun. I have never searched for other people's ancestors. Perhaps that is fun. When I· started, the only Turrentines that I knew were my uncles ani aunts and their children. Now I have a card file of mOre than 2,000 Turrentines living and dead. I began writing letters and· before long my correspondence ¥las so heavy .that I began a mimeographed newsletter to my expanded family. I have published that newsletter for more than 22 years and have a mailing list of about 500 families • .- . ' . .,.". We conceived·theidea·of a family reunion and heldthe first in 1941 in Hillsboro, N.C., t.he.,ancestral home of the family in colonial days. Since that time we·have.held reunions in Lockesburg,Ark.; Shelbyville, Tenn;; Marionville, Mo.;· Gadsden, Ala.; Chapel Hill, N.C.; and in Russellville, Ark. ,Our next reunion will be in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963. We hope to continue our reunions in. odd-numbered years. ' I have had many thrills in my'search for ~ncestors.Manythrills have come at unexpected times and in unexpected places. -

F:\Family Law\Ready to Send\05 Nickelson.Wpd

USING SUMMARY JUDGMENT PROCEDURE IN FAMILY LAW CASES CHRIS NICKELSON 5201 West Freeway, Suite 100 Fort Worth, Texas 76107 State Bar of Texas ADVANCED FAMILY LAW DRAFTING December 9-10, 2010 Houston CHAPTER 5 BIOGRAPHY CHRIS NICKELSON LAW OFFICE OF GARY L. NICKELSON 5201 West Freeway, Suite 100 Fort Worth, Texas 76107 817-735-4000 FAX: 817-735-1480 EDUCATION J.D. from Texas Tech University School of Law, 1999 B.A. from The University of Texas at Austin, 1996 EMPLOYMENT BACKGROUND Law Office of Gary L. Nickelson, 2008-present Partner with Shannon, Gracey, Ratliff & Miller, L.L.P., 2005-2007 Associate with Shannon, Gracey, Ratliff & Miller, L.L.P., 2001-2004 Staff Attorney to Justice David Chew of the El Paso Court of Appeals, 2000 Law Clerk to Justice Ann McClure of the El Paso Court of Appeals, 1999-2000 OFFICES HELD Member, Family Law Council, State Bar of Texas Family Law Section 2010-2015 Director, Tarrant County Bar Association Board of Directors, 2008-2009 Chair of the Tarrant County Bar Association Appellate Section, 2008-2009 Vice-Chair of the Tarrant County Appellate Section, 2007-2008 Secretary of the Tarrant County Appellate Section, 2006-2007 HONORS RECEIVED Board Certified in Civil Appellate Law, 2006-present Rising Star, Texas Monthly Magazine 2004-2010 Top Attorney, Fort Worth Magazine, 2007-2010 CLE ACTIVITIES • Co-Author and Co-Presenter of Appellate Practice from Every Angle, 2010 State Bar of Texas Advanced Family Law Course. • Co-Author and Presenter of Proving Separate Property: An Argument for More Use of Summary Judgment Practice in Family Law Cases, 2010 State Bar of Texas Advanced Family Law Course. -

Gender, Language, and Wills Karen J

Marquette Law Review Volume 98 Article 3 Issue 4 Summer 2015 Not Your Mother's Will: Gender, Language, and Wills Karen J. Sneddon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Repository Citation Karen J. Sneddon, Not Your Mother's Will: Gender, Language, and Wills, 98 Marq. L. Rev. 1535 (2015). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol98/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW Volume 98 Summer 2015 Number 4 NOT YOUR MOTHER’S WILL: GENDER, LANGUAGE, AND WILLS KAREN J. SNEDDON* “Boys will be boys, but girls must be young ladies” is an echoing patriarchal refrain from the past. Formal equality has not produced equality in all areas, as demonstrated by the continuing wage gap. Gender bias lingers and can be identified in language. This Article focuses on Wills, one of the oldest forms of legal documents, to explore the intersection of gender and language. With conceptual antecedents in pre-history, written Wills found in Ancient Egyptian tombs embody the core characteristics of modern Wills. The past endows the drafting and implementation of Wills with a wealth of traditions and experiences. The past, however, also entombs patriarchal notions inappropriate in Wills of today. This Article explores the language of the Will to parse the historical choices that remain relevant choices for today and the vestiges of a patriarchal past that should be avoided. -

Legal Research Institute Focused on the Finer Points of Legal Research

Every other year the Law Library Association of Welcome! Maryland (LLAM) sponsors a day-long conference. In the past, LLAM's Legal Research Institute focused on the finer points of legal research. This year LLAM has decided to do something different. This year's conference highlights best practices of librarians, not just law librarians, but all types of librarians. Full Disclosure: Librarians Sharing Best Practices will not be an ordinary library conference—by the end of the day participants will hear almost a dozen librarians share their best practices, successes, and even Law Library Association of Maryland Law Library failures. The micro-presentation format will enable all of us to hear and learn from many people in a single day. It will be an exceptional networking opportunity and a chance to learn from colleagues. We hope you enjoy the day. Legal Research Institute Sara Witman President, Law Library Association of Maryland FULL DISCLOSURE LEGAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE Keynote Speakers Maureen Sullivan Steve Anderson Vice President and Present-Elect of the American Vice President and Present-Elect of the Library Association American Association of Law Libraries Maureen Sullivan, the vice president/president-elect Steve Anderson, the vice president/ of the American Library Association (ALA), is an president-elect of the American Association organization development consultant with over of Law Libraries (AALL), is director of the twenty five years' experience providing Maryland State Law Library, a position he organizational and leadership development, strategic has held since 2005. Prior to that planning, change management, and training to appointment, he served as director of libraries and information organizations. -

Special Libraries Aerojet Redmond Operations

Special Libraries Aerojet Redmond Operations Business and Industry Boeing Company, The Library and Learning Center Services PO Box 3707, MC 62-LC Aerojet Redmond Operations Seattle 98124-2207 (425) 965-3255 Technical Library 51 PO Box 97009 FTEs: M-F 7am-4:30pm Redmond 98073-9709 Hours: OCLC: BOI; DocLine: WAUBOE (425) 885-5000 x 5414; Fax: (425) 882-5754 ILL Institution Code(s): Aerodynamics; aeronautics; air [email protected] Special Collections: transportation; business; computer technology; engineering; FTEs: 1 electronics; materials; structures. Hours: M-Th 7am-4pm; F 7am-noon ILL Institution Code(s): OCLC: RRD Staff: Special Collections: Monopropellant and bipropellant rocket Mgr: Barbie Whorton (425) 237-7886 engines; electric propulsion systems; spacecraft propulsion systems; [email protected] gas generators; fire suppression and safety systems Staff: Librn: James Gurley (425) 885-5000 x 5414 EJB Facilities Services Technical Reference Center, Bldg T035 Naval Subase Kitsap, Bangor APA - The Engineered Wood Association Silverdale 98315-5070 (360) 396-4636 7011 S 19th St M-F 7:30am-4pm Tacoma 98466-5333 Hours: Government documents (253) 565-6600 x 461; Fax: (253) 565-7265 Special Collections: FTEs: 1 Staff: Hours: M-F 8am-4pm (not open to the public) Librn: Patricia Spleen (360) 396-4636 Special Collections: Plywood and wood products; forestry Staff: Barbara J Embrey (253) 565-6600 x 461 Golder Associates Inc. Corporate Library [email protected] 18300 NE Union Hill Rd, Ste 200 Redmond 98052-3391 (425) 883-0777; -

Caldwell's Kentucky Form Book, Fifth Edition

Caldwell's Kentucky Form Book, Fifth Edition Release 01, May 2006 Forms on Disc – Forms List [Bolded forms indicate Official Forms with HotDocs® Fillable functionality] Form Title Chapter 1 Attorney and Client 1.01 Contingency Fee Employment Contract 1.02 Fixed Fee Agreement 1.03 Hourly Fee Agreement Chapter 2 Small Claims Court 2.01 Complaint (AOC 175) 2.02 Jefferson District Court Checklist 2.03 Summons (AOC 180) 2.04 Counter-Claim (AOC 185) 2.05 Post Judgment Interrogatories (AOC 197) 2.06 Post Judgment Motion/Order Requiring Losing Party to Answer Interrogatories (AOC 198) 2.07 Notice of Transfer of Action (AOC 122) (PDF format) Chapter 3 District Courts 3.01 Civil Summons (AOC 105) 3.02 Third-Party Summons (AOC 120) 3.03 Appointment of Warning Order Attorney (AOC 110) 3.04 Subpoena (AOC 025) 3.05 Waiver of Recording (AOC 040) 3.06 Notice of Transfer of Action (AOC 122) (PDF format) 3.07 Bill of Costs (AOC 130) Chapter 4 Circuit Court 4.01 Bill of Costs (AOC 130) 4.02 Summons; Civil Action (AOC 105) 4.03 Appointment of a Warning Order Attorney (AOC 110) 4.04 Subpoena (AOC 025) 4.05 Third Party Summons (AOC 120) 4.06 Supersedeas Bond (AOC 155) 4.07 Order Setting for Trial (AOC 030) Chapter 5 Family Court 5.01 DNA Petition (AOC DNA-1) 5.02 Emergency Custody Order Affidavit (AOC DNA-2.1) 5.03 Order for Attorney's Fees (AOC DNA-8) 5.04 Financial Statement Affidavit of Indigencey, Request for Counsel and Order (AOC DNA-11) 5.05 Uniform Child Support Order (AOC 152) 5.06 Notice & Affidavit of Foreign Judgment Registration (AOC 160) (PDF format) 5.07 Notice of Registration of Foreign Child Custody Order (AOC 165) (PDF format) 5.08 Confirmation of Registration of Foreign Child Custody Order (AOC 166) (PDF format) 5.09 Petition/Order for Permission to Marry (AOC 201) 5.10 Dissolution of Marriage Findings of Fact/Conclusions of Law (AOC 245) (PDF format) 5.11 Domestic Violence Petition/Motion (AOC 275.1) 5.12 Petition for Name Change (AOC 295) 5.13 Name Change Order (AOC 296) 1 Bolded forms indicate Official Forms with HotDocs® Fillable functionality. -

Book 2 Standard Terms and Conditions for Construction Contracts

BOOK 2 STANDARD TERMS AND CONDITIONS FOR CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS CONTRACT NO. C1580 EMILIANO ZAPATA ACADEMY ANNEX 2728 SOUTH KOSTNER AVENUE CHICAGO, IL 60623 PROJECT #05055 PUBLIC BUILDING COMMISSION OF CHICAGO Mayor Rahm Emanuel Chairman Carina E. Sánchez Executive Director Room 200 Richard J. Daley Center 50 West Washington Street Chicago, Illinois 60602 312-744-3090 www.pbcchicago.com ISSUED FOR BID ON 7/28/2017 JUNE 2017 Date of Issue: July 28, 2017 Book 2_Standard Terms and Conditions for Construction Contracts Page 1 of 163 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Date of Issue: July 28, 2017 Book 2_Standard Terms and Conditions for Construction Contracts Page 2 of 163 PUBLIC BUILDING COMMISSION OF CHICAGO TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS 1 SECTION 1.01 DEFINITIONS.................................................................................................................................................... 1 SECTION 1.02 INTERPRETATION / RULES ................................................................................................................................ 3 SECTION 1.03 STANDARD SPECIFICATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 4 SECTION 1.04 SEVERABILITY ................................................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1.05 ENTIRE AGREEMENT.......................................................................................................................................