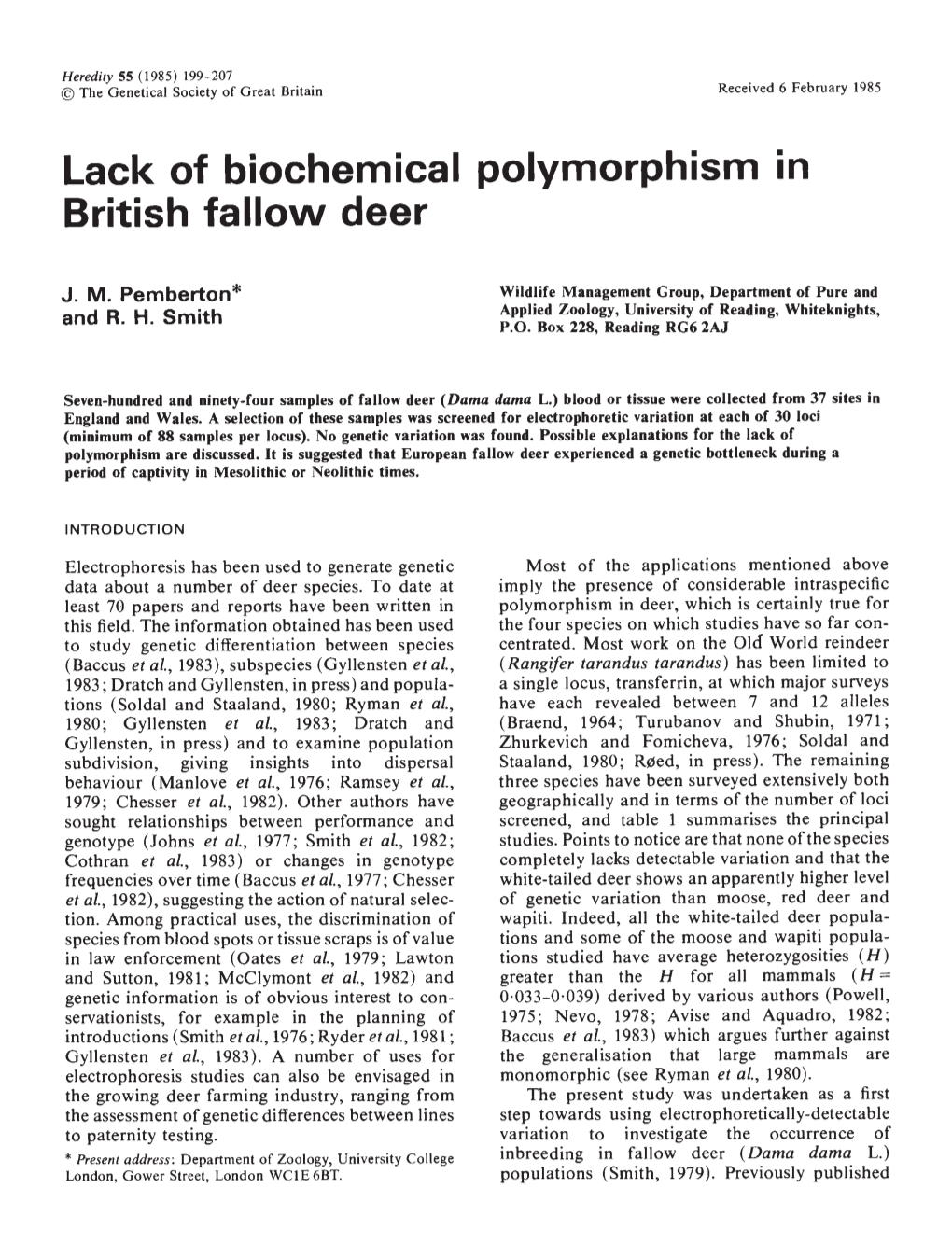

British Fallow Deer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017 Elisabeth Patton, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM Veterinary Program Manager Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection Division of Animal Health Why Use the Serologic Test? Employ newer, accurate diagnostic test technology Minimizes capture and handling events for animal safety Expected to promote additional cervid TB testing • Requested by USAHA and cervid industry Comparable sensitivity and specificity to skin tests 2 Historical Timeline 3 Stat-Pak licensed for elk and red deer, 2009 White-tailed and fallow deer, 2010-11 2010 - USAHA resolution - USDA evaluate Stat-Pak as official TB test 2011 – Project to evaluate TB serologic tests in cervids (Cervid Serology Project); USAHA resolution to approve Oct 2012 – USDA licenses the Dual-Path Platform (DPP) secondary test for elk, red deer, white-tailed deer, and fallow deer Improved specificity compared to Stat-Pak Oct 2012 – USDA approves the Stat-Pak (primary) and DPP (secondary) as official bovine TB tests in elk, red deer, white- tailed deer, fallow deer and reindeer Recent Actions Stat-Pak is no longer in production 9 CFR 77.20 has been amended to approve the DPP as official TB program test. An interim rule was published on 9 January 2013 USDA APHIS created a Guidance Document (6701.2) to provide instructions for using the tests https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_ diseases/tuberculosis/downloads/vs_guidance_670 1.2_dpp_testing.pdf 4 Cervid Serology Project Objective 5 Evaluate TB detection tests for official bovine tuberculosis (TB) program use in captive and free- ranging cervids North American elk (Cervus canadensis) White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) Primary/screening test AND Secondary Test: Dual Path Platform (DPP) Rapid immunochromatographic lateral-flow serology test Detect antibodies to M. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Eight Sudanese Camel Contagious Ecthyma Viruses Based on B2L Gene Sequence Abdelmalik I

Khalafalla et al. Virology Journal (2015) 12:124 DOI 10.1186/s12985-015-0348-7 RESEARCH Open Access Phylogenetic analysis of eight sudanese camel contagious ecthyma viruses based on B2L gene sequence Abdelmalik I. Khalafalla1,2* , Ibrahim M. El-Sabagh3,4, Khalid A. Al-Busada5, Abdullah I. Al-Mubarak6 and Yahia H. Ali7 Abstract Background: Camel contagious ecthyma (CCE) is an important viral disease of camelids caused by a poxvirus of the genus parapoxvirus (PPV) of the family Poxviridae. The disease has been reported in west and east of the Sudan causing economical losses. However, the PPVs that cause the disease in camels of the Sudan have not yet subjected to genetic characterization. At present, the PPV that cause CCE cannot be properly classified because only few isolates that have been genetically analyzed. Methods and results: PCR was used to amplify the B2L gene of the PPV directly from clinical specimens collected from dromedary camels affected with contagious ecthyma in the Sudan between 1993 and 2013. PCR products were sequenced and subjected to genetic analysis. The results provided evidence for close relationships and genetic variation of the camel PPV (CPPV) represented by the circulation of both Pseudocowpox virus (PCPV) and Orf virus (ORFV) strains among dromedary camels in the Sudan. Based on the B2L gene sequence the available CPPV isolates can be divided into two genetic clades or lineages; the Asian lineage represented by isolates from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and India and the African lineage comprising isolates from the Sudan. Conclusion: The camel parapoxvirus is genetically diverse involving predominantly viruses close to PCPV in addition to ORFVs, and can be divided into two genetically distant lineages. -

Baylisascariasis

Baylisascariasis Importance Baylisascaris procyonis, an intestinal nematode of raccoons, can cause severe neurological and ocular signs when its larvae migrate in humans, other mammals and birds. Although clinical cases seem to be rare in people, most reported cases have been Last Updated: December 2013 serious and difficult to treat. Severe disease has also been reported in other mammals and birds. Other species of Baylisascaris, particularly B. melis of European badgers and B. columnaris of skunks, can also cause neural and ocular larva migrans in animals, and are potential human pathogens. Etiology Baylisascariasis is caused by intestinal nematodes (family Ascarididae) in the genus Baylisascaris. The three most pathogenic species are Baylisascaris procyonis, B. melis and B. columnaris. The larvae of these three species can cause extensive damage in intermediate/paratenic hosts: they migrate extensively, continue to grow considerably within these hosts, and sometimes invade the CNS or the eye. Their larvae are very similar in appearance, which can make it very difficult to identify the causative agent in some clinical cases. Other species of Baylisascaris including B. transfuga, B. devos, B. schroeder and B. tasmaniensis may also cause larva migrans. In general, the latter organisms are smaller and tend to invade the muscles, intestines and mesentery; however, B. transfuga has been shown to cause ocular and neural larva migrans in some animals. Species Affected Raccoons (Procyon lotor) are usually the definitive hosts for B. procyonis. Other species known to serve as definitive hosts include dogs (which can be both definitive and intermediate hosts) and kinkajous. Coatimundis and ringtails, which are closely related to kinkajous, might also be able to harbor B. -

Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human-Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2017 Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human-Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management Jarod D. Raithel Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Raithel, Jarod D., "Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human- Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management" (2017). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 6633. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6633 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEGRATING BLACK BEAR BEHAVIOR, SPATIAL ECOLOGY, AND POPULATION DYNAMICS IN A HUMAN-DOMINATED LANDSCAPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT by Jarod D. Raithel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Ecology Approved: _______________________ _______________________ Lise M. Aubry, Ph.D. Melissa J. Reynolds-Hogland, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member _______________________ _______________________ David N. Koons, Ph.D. Eric M. Gese, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _______________________ _______________________ Joseph M. Wheaton, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2017 ii Copyright Jarod Raithel 2017 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human-Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management by Jarod D. -

Differential Habitat Selection by Moose and Elk in the Besa-Prophet Area of Northern British Columbia

ALCES VOL. 44, 2008 GILLINGHAM AND PARKER – HABITAT SELECTION BY MOOSE AND ELK DIFFERENTIAL HABITAT SELECTION BY MOOSE AND ELK IN THE BESA-PROPHET AREA OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA Michael P. Gillingham and Katherine L. Parker Natural Resources and Environmental Studies Institute, University of Northern British Columbia, 3333 University Way, Prince George, British Columbia, Canada V2N 4Z9, email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Elk (Cervus elaphus) populations are increasing in the Besa-Prophet area of northern British Columbia, coinciding with the use of prescribed burns to increase quality of habitat for ungu- lates. Moose (Alces alces) and elk are now the 2 large-biomass species in this multi-ungulate, multi- predator system. Using global positioning satellite (GPS) collars on 14 female moose and 13 female elk, remote-sensing imagery of vegetation, and assessments of predation risk for wolves (Canis lupus) and grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), we examined habitat use and selection. Seasonal ranges were typi- cally smallest for moose during calving and for elk during winter and late winter. Both species used largest ranges in summer. Moose and elk moved to lower elevations from winter to late winter, but subsequent calving strategies differed. During calving, moose moved to lowest elevations of the year, whereas elk moved back to higher elevations. Moose generally selected for mid-elevations and against steep slopes; for Stunted spruce habitat in late winter; for Pine-spruce in summer; and for Subalpine during fall and winter. Most recorded moose locations were in Pine-spruce during late winter, calv- ing, and summer, and in Subalpine during fall and winter. -

Deer, Elk, Bear, Moose, Lynx, Bobcat, Waterfowl

Hunt ID: 1501-CA-AL-G-L-MDeerWDeerElkBBearMooseLynxBobcatWaterfowl-M1SR-O1G-N2EGE Great Economy Deer and Moose Hunts south of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada American Hunters trekking to Canada for low cost moose, along with big Mule Deer and Whitetail and been pleasantly surprised by the weather and temperatures that they were greeted by when they hunted British Columbia, located in Canada, north of Washington State. Canada should be and is cold but there are exceptions, if you know where to go. In BC if you stay on the western Side of the Rocky Mountains the weather is quite mild because it is warmed by the Pacific Ocean. If you hunt east of the Rocky Mountains, what I call the Canadian Interior it can be as much as 50 degrees colder depending on the time of the year. The area has now preference point requirements, the Outfitter has his allotted vouchers so you can get a reasonably priced license and, in most cases, less than you can get for the same animal in the US as a non-resident. You don’t even buy the voucher from the Outfitter it is part of his hunt cost because without it you could not get a license anyway. Travel is easy and the residents are friendly. Like anywhere outside the US you will need a easy to acquire Passport if you don’t have one, just don’t wait until the last minute to get one for $10 from your local Post office by where you live. The one thing in Canada is if you have a felony on your record Canada will not allow you into their safe Country. -

Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist

STATE OF NEVADA Steve Sisolak, Governor DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Tony Wasley, Director GAME DIVISION Brian F. Wakeling, Chief Mike Cox, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Staff Specialist Pat Jackson, Predator Management Staff Specialist Cody McKee, Elk Staff Biologist Cody Schroeder, Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist Western Region Southern Region Eastern Region Regional Supervisors Mike Scott Steve Kimble Tom Donham Big Game Biologists Chris Hampson Joe Bennett Travis Allen Carl Lackey Pat Cummings Clint Garrett Kyle Neill Cooper Munson Sarah Hale Ed Partee Kari Huebner Jason Salisbury Matt Jeffress Kody Menghini Tyler Nall Scott Roberts This publication will be made available in an alternative format upon request. Nevada Department of Wildlife receives funding through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration. Federal Laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex, or disability. If you believe you’ve been discriminated against in any NDOW program, activity, or facility, please write to the following: Diversity Program Manager or Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Nevada Department of Wildlife 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Mailstop: 7072-43 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Suite 120 Arlington, VA 22203 Reno, Nevada 8911-2237 Individuals with hearing impairments may contact the Department via telecommunications device at our Headquarters at 775-688-1500 via a text telephone (TTY) telecommunications device by first calling the State of Nevada Relay Operator at 1-800-326-6868. NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE 2018-2019 BIG GAME STATUS This program is supported by Federal financial assistance titled “Statewide Game Management” submitted to the U.S. -

An Analysis of the Phylogenetic Relationship of Thai Cervids Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of Protein Kinase C Iota (PRKCI) Intron

Kasetsart J. (Nat. Sci.) 43 : 709 - 719 (2009) An Analysis of the Phylogenetic Relationship of Thai Cervids Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of Protein Kinase C Iota (PRKCI) Intron Kanita Ouithavon1, Naris Bhumpakphan2, Jessada Denduangboripant3, Boripat Siriaroonrat4 and Savitr Trakulnaleamsai5* ABSTRACT The phylogenetic relationship of five Thai cervid species (n=21) and four spotted deer (Axis axis, n=4), was determined based on nucleotide sequences of the intron region of the protein kinase C iota (PRKCI) gene. Blood samples were collected from seven captive breeding centers in Thailand from which whole genomic DNA was extracted. Intron1 sequences of the PRKCI nuclear gene were amplified by a polymerase chain reaction, using L748 and U26 primers. Approximately 552 base pairs of all amplified fragments were analyzed using the neighbor-joining distance matrix method, and 19 parsimony- informative sites were analyzed using the maximum parsimony approach. Phylogenetic analyses using the subfamily Muntiacinae as outgroups for tree rooting indicated similar topologies for both phylogenetic trees, clearly showing a separation of three distinct genera of Thai cervids: Muntiacus, Cervus, and Axis. The study also found that a phylogenetic relationship within the genus Axis would be monophyletic if both spotted deer and hog deer were included. Hog deer have been conventionally classified in the genus Cervus (Cervus porcinus), but this finding supports a recommendation to reclassify hog deer in the genus Axis. Key words: Thailand, the family Cervidae, protein kinase C iota (PRKCI) intron, phylogenetic tree, taxonomy INTRODUCTION 1987; Gentry, 1994). Cervids, or what is commonly called “deer,” are mostly characterized The family Cervidae is one of the most by antlers with a bony inner core and velvet skin specious families of artiodactyls, with an extensive cover. -

Muskox Management Report Alaska Dept of Fish and Game Wildlife

Muskox Management Report of survey-inventory activities 1 July 1998–30 June 2000 Mary V. Hicks, Editor Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation December 2001 ADF&G Please note that population and harvest data in this report are estimates and may be refined at a later date. If this report is used in its entirety, please reference as: Alaska Department of Fish and Game. 2001. Muskox management report of survey-inventory activities 1 July 1998–30 June 2000. M.V. Hicks, editor. Juneau, Alaska. If used in part, the reference would include the author’s name, unit number, and page numbers. Authors’ names can be found at the end of each unit section. Funded in part through Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration, Proj. 16, Grants W-27-2 and W-27-3. LOCATION 2 GAME MANAGEMENT UNIT: 18 (41,159 mi ) GEOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION: Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta BACKGROUND NUNIVAK ISLAND Muskoxen were once widely distributed in northern and western Alaska but were extirpated by the middle or late 1800s. In 1929, with the support of the Alaska Territorial Legislature, the US Congress initiated a program to reintroduce muskoxen in Alaska. Thirty-one muskoxen were introduced from Greenland to Nunivak Island in Unit 18 during 1935–1936, as a first step toward reintroducing this species to Alaska. The Nunivak Island population grew slowly until approximately 1958 and then began a period of rapid growth. The first hunting season was opened in 1975, and the population has since fluctuated between 400 and 750 animals, exhibiting considerable reproductive potential, even under heavy harvest regimes. -

BISON Workshop Slides

Bison Workshop Implicit, parallel, fully-coupled nuclear fuel performance analysis Computational Mechanics and Materials Department Idaho National Laboratory Table of ContentsI Bison Overview . 4 Getting Started with Bison . 19 Git...........................................................20 Building Bison . 28 Cloning to a New Machine . 30 Contributing to Bison. .31 External Users. .35 Thermomechanics Basics . 37 Heat Conduction . 40 Solid Mechanics . 55 Contact . 66 Fuels Specific Models . 80 Example Problem . 89 Mesh Generation. .132 Running Bison . 147 Postprocessing. .159 Best Practices and Solver Options (Advanced Topic) . 224 Adding a New Material Model to Bison . 239 2 / 277 Table of ContentsII Adding a Regression Test to bison/test . 261 Additional Information . 273 References . 276 3 / 277 Bison Overview Bison Team Members • Rich Williamson • Al Casagranda – [email protected] – [email protected] • Steve Novascone • Stephanie Pitts – [email protected] – [email protected] • Jason Hales • Adam Zabriskie – [email protected] – [email protected] • Ben Spencer • Wenfeng Liu – [email protected] – [email protected] • Giovanni Pastore • Ahn Mai – [email protected] – [email protected] • Danielle Petersen • Jack Galloway – [email protected] – [email protected] • Russell Gardner • Christopher Matthews – [email protected] – [email protected] • Kyle Gamble – [email protected] 5 / 277 Fuel Behavior: Introduction At beginning of life, a fuel element is quite simple... Michel et al., Eng. Frac. Mech., 75, 3581 (2008) Olander, p. 323 (1978) =) Fuel Fracture Fission Gas but irradiation brings about substantial complexity... Olander, p. 584 (1978) Bentejac et al., PCI Seminar (2004) Multidimensional Contact and Stress Corrosion Deformation Cracking Cladding Nakajima et al., Nuc. -

Fitzhenry Yields 2016.Pdf

Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za iii GENERAL ABSTRACT Fallow deer (Dama dama), although not native to South Africa, are abundant in the country and could contribute to domestic food security and economic stability. Nonetheless, this wild ungulate remains overlooked as a protein source and no information exists on their production potential and meat quality in South Africa. The aim of this study was thus to determine the carcass characteristics, meat- and offal-yields, and the physical- and chemical-meat quality attributes of wild fallow deer harvested in South Africa. Gender was considered as a main effect when determining carcass characteristics and yields, while both gender and muscle were considered as main effects in the determination of physical and chemical meat quality attributes. Live weights, warm carcass weights and cold carcass weights were higher (p < 0.05) in male fallow deer (47.4 kg, 29.6 kg, 29.2 kg, respectively) compared with females (41.9 kg, 25.2 kg, 24.7 kg, respectively), as well as in pregnant females (47.5 kg, 28.7 kg, 28.2 kg, respectively) compared with non- pregnant females (32.5 kg, 19.7 kg, 19.3 kg, respectively). -

Horned Animals

Horned Animals In This Issue In this issue of Wild Wonders you will discover the differences between horns and antlers, learn about the different animals in Alaska who have horns, compare and contrast their adaptations, and discover how humans use horns to make useful and decorative items. Horns and antlers are available from local ADF&G offices or the ARLIS library for teachers to borrow. Learn more online at: alaska.gov/go/HVNC Contents Horns or Antlers! What’s the Difference? 2 Traditional Uses of Horns 3 Bison and Muskoxen 4-5 Dall’s Sheep and Mountain Goats 6-7 Test Your Knowledge 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2018 Issue 8 1 Sometimes people use the terms horns and antlers in the wrong manner. They may say “moose horns” when they mean moose antlers! “What’s the difference?” they may ask. Let’s take a closer look and find out how antlers and horns are different from each other. After you read the information below, try to match the animals with the correct description. Horns Antlers • Made out of bone and covered with a • Made out of bone. keratin layer (the same material as our • Grow and fall off every year. fingernails and hair). • Are grown only by male members of the • Are permanent - they do not fall off every Cervid family (hoofed animals such as year like antlers do. deer), except for female caribou who also • Both male and female members in the grow antlers! Bovid family (cloven-hoofed animals such • Usually branched.