D:\CHABELA\Walker, Eduardo\AB A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empresas Copec S.A. Consolidated Financial

EMPRESAS COPEC S.A. CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2018 IFRS - International Financial Reporting Standards IAS - International Accounting Standards NIFCH - Chilean Financial Reporting Standards IFRIC - International Financial Reporting Interpretations Committee US$ - United States dollars ThUS$ - Thousands of US dollars MUS$ - Millions of US dollars MCh$ - Millions of Chilean Pesos COP$ - Colombian pesos S./ - Peruvian nuevo sol WorldReginfo - d6a34cd4-9970-4f3e-9bfb-af0f71482286 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT Santiago, March 8, 2019 Dear Shareholders and Directors Empresas Copec S.A. We have audited the accompanying consolidated financial statements of Empresas Copec S.A. and affiliates, which comprise a consolidated statement of financial position as of December 31, 2018 and 2017, the corresponding consolidated statements of income by function, consolidated comprehensive income, consolidated changes in equity and consolidated cash flow for the years ending on these dates, and the corresponding notes to the consolidated financial statements. Management's responsibility for the consolidated financial statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these consolidated financial statements in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). This responsibility includes the design, implementation and maintenance of relevant internal controls for the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether -

The Santiago Exchange Indices Methodology Consultation

The Santiago Exchange Indices Methodology Consultation SANTIAGO, APRIL 2, 2018: In August 2016, the Santiago Exchange (the “Exchange”) and S&P Dow Jones Indices (“S&P DJI”) signed an Index Operation and License Agreement. The Exchange’s partnership with S&P DJI, the world’s leading provider of index-based concepts, data and research, includes the adoption of international index methodology standards and the integration of operational processes and business strategies and enhances the visibility, governance, and transparency of the existing indices. The agreement also enables the development, licensing, distribution and management of current and future indices which will be designed to serve as innovative and practical tools for local and global investors. The new and existing Santiago Exchange indices will be co-branded under the “S&P/CLX” name (the “Indices”) that can be used to underlie liquid financial products, expanding the breadth and depth of the Chilean capital market. As part of this transition, S&P DJI and the Exchange are conducting a consultation with members of the investment community on potential changes to the following Santiago Exchange indices to ensure that they continue to meet their objectives and are aligned with the needs of local and international market participants. • Indice General de Precios y Acciones (“IGPA”) • IGPA Large, IGPA Mid, and IGPA Small (collectively “IGPA Size Indices”) • Indice de Precios Selectivo de Acciones (“IPSA”) IGPA The IGPA is designed to serve as a broad country benchmark of the Chilean market. Based on a review of the index’s methodology and existing data, and to ensure that the index continues to satisfy its objective, S&P DJI and the Exchange are proposing to increase the minimum bursatility presence1 required for index eligibility. -

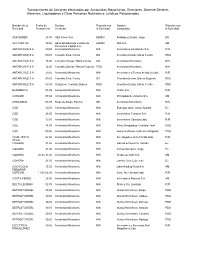

Transacciones De Acciones Efectuadas Por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General

Transacciones de Acciones efectuadas por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General, Nombre de la Fecha de Nombre Relación con Nombre Relación con Sociedad Transacción Vendedor la Sociedad Comprador la Sociedad ANDACOR 18.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Leatherbee Grant, Michael DG ANDACOR 18.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Leatherbee Grant, Peter James AM ANTARCHILE S A 07.01 Inversiones Peñuelas Limitada PJR Accionista Minoritario NIN ANTARCHILE S A 07.01 Inversiones Peñuelas Limitada PJR Rentas ASM Limitada U ANTARCHILE S A 07.01 Inversiones Peñuelas Limitada PJR Rentas AEB Limitada U BAJOS DE MENA 18.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Celfin Capital S.A. C. de B. AM BAJOS DE MENA 07.01-08.01 Celfin Capital S.A. C. de B. AM Accionista Minoritario NIN BAJOS DE MENA 11.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Viviani Canello, Víctor DG BESALCO S.A. 15.01-24.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Don Víctor S.A. AM CAP S.A. 28.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN De Andraca Adriasola, Daniela PDG CAROZZI 14.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Principado de Asturias S.A. AM CEMENTO BIO 23.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Sturms Stein, Cristian DG BIO COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Agricola e Inmobiliaria La Maison S.A. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Santa Victoria Ltda. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Santa Marta Ltda. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Tisil Ltda. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Guallatiri Ltda. AM COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones San Pablo S.A. PJR CURAUMA 10.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Soc. -

Nómina De Acciones

NÓMINA DE ACCIONES NÓMINA DE ACIONES QUE CUMPLEN REQUISITOS PARA SER CONSIDERADAS EN CATEGORÍAS GENERALES DE INVERSIÓN REPORTE TRIMESTRAL NÓMINA DE ACCIONES QUE CUMPLEN REQUISITOS PARA SER CONSIDERADAS EN CATEGORÍAS GENERALES DE INVERSIÓN La Superintendencia de Pensiones emitió la Circular N° 2.026 que deroga la Circular N° 2.010, relativa a los Parámetros para el cálculo de los límites de inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones y Fondos de Cesantía, la que entrará en vigencia el 20 de marzo de 2018. En la Circular, se publica la nómina de las acciones de sociedades anónimas abiertas nacionales que cumplen con los requisitos definidos por el Régimen de Inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones, para ser consideradas en las categorías generales de inversión. Cabe señalar que aquellas acciones que no cumplan con los requisitos antes señalados, podrán ser adquiridas bajo las condiciones establecidas para la categoría restringida, definida en el citado Régimen. El detalle de esta información se encuentra a continuación: ACCIONES DE SOCIEDADES ANÓNIMAS ABIERTAS 1. De acuerdo a lo dispuesto en el inciso sexto del artículo 45 del D.L 3.500 de 1980 y en el Régimen de Inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones las acciones elegibles en categoría general, tanto por instrumento como por emisor, a partir del 20 de marzo de 2018, en virtud del cumplimiento del requisito de presencia ajustada mayor o igual a 25% o contar con un Market Maker en los términos y condiciones establecidos en la Normativa vigente, son las siguientes: RAZÓN SOCIAL NEMOTÉCNICO SERIE AES GENER S.A. AESGENER ÚNICA AGUAS ANDINAS S.A. -

Articles-15829 Recurso 1.Pdf

Transacciones de Acciones efectuadas por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General, Gerentes, Liquidadores y Otras Personas Naturales o Jurídicas Relacionadas Nombre de la Fecha de Nombre Relación con Nombre Relación con Sociedad Transacción Vendedor la Sociedad Comprador la Sociedad AES GENER 28.05 AES Gener S.A. EMISO Rodríguez Grossi, Jorge DG AFP CAPITAL 30.05 Administradora de Fondos de EMISO ING S.A. AM Pensiones Capital S.A. ANTARCHILE S A 29.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Limatambo S.A. PJR ANTARCHILE S A 09.05 Croxatto Silva, Carlos DG Croxatto Ortuzar, María Cecilia PDG ANTARCHILE S A 16.05 Croxatto Ortuzar, María Cecilia DG Accionista Minoritario NIN ANTARCHILE S A 16.05 Croxatto Ortuzar, Blanca Eugenia PDG Accionista Minoritario NIN ANTARCHILE S A 29.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones y Rentas Ancabela Ltda. PJR ANTARCHILE S A 09.05 Croxatto Silva, Carlos DG Croxatto Ortuzar, Blanca Eugenia PDG ANTARCHILE S A 09.05 Ortuzar de Croxatto, Blanca PDG Croxatto Ortuzar, María Cecilia PDG BANMEDICA 05.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Green S.A. PJR CAROZZI 07.04 Accionista Minoritario NIN Principado de Asturias S.A. AM CENCOSUD 08.05 Rivas de Diego, Patricio GE Accionista Minoritario NIN CGE 20.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Estrougo Ortiz, Jaime Azarias EJ CGE 28.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Tunquen S.A. PJR CGE 13.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Caucura Ltda. PJR CGE 14.03 Accionista Minoritario NIN Pérez Respaldiza, Cristobal José PDG CGE 09.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Heinsen Widow, Gabrielle Margarita PDG CLUB HIPICO 02.06 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inv. Ongolmo de la Florida Ltda. -

Informe Semanal 08-05-2020

Informe Semanal N°1124 08 de mayo de 2020 Departamento de Estudios Informe Semanal Empresas CMPC - Actualización de Estimaciones y Precio Objetivo ante un Portada menor precio proyectado para la celulosa. Empresas CMPC - Actualización de Estimaciones y Precio Objetivo ante un Reiteramos nuestra recomendación de menor precio proyectado para la celulosa. Mantener. Reiteramos nuestra recomendación de Mantener. Ajuste de estimaciones – Hemos actualizado nuestro modelo de CMPC para Pág. 1 incorporar: (i) las más recientes estimaciones macroeconómicas y de tipo de cambio del equipo de Citi. En este sentido, y como un productor de celulosa de mercado orientado a la exportación con bases productivas en Chile y Brasil, la Comentario de Mercado reciente depreciación del peso chileno y real brasileño, en un contexto de precios Reinicio de negociaciones comerciales estables de la celulosa, ha tenido un impacto positivo en sus costos de producción. toman protagonismo en medio de crisis por Por el contrario, lo anterior ha deteriorado los ingresos de Softys (división de COVID-19 tissue y productos sanitarios), principalmente denominados en monedas locales; Pág. 2 (ii) una revisión a la baja de nuestras proyecciones de precios para la celulosa (- 5% y -10% para 2020 y 2021, respectivamente); (iii) mayores volúmenes de ventas de productos del área tissue a fines de marzo debido a una mayor compra Noticias de la Semana de pánico en medio del brote de COVID-19; y (iv) otros ajustes menores, tales Itaú Corpbanca / BCI / Empresas COPEC / como el retraso en el mantenimiento de las plantas de celulosa. Con todo, nuestra Enel Américas / Enel Chile / Monitor estimación de EBITDA para 2020 se redujo en un 11% a US$ 1,08 billones (-8% Semanal de Precios de la Celulosa / a/a). -

Transacciones De Acciones Efectuadas Por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General

Transacciones de Acciones efectuadas por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General, Nombre de la Fecha de Nombre Relación con Nombre Relación con Sociedad Transacción Vendedor la Sociedad Comprador la Sociedad ANDINA 21.12-28.12 Inversiones San Andres Limitada PJR Inversiones Nueva Sofia Limitada PJR ANDINA 21.12 Inversiones San Andres Limitada PJR Inversiones Dolovan Chile Ltda. PJR ANTARCHILE S A 21.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Bodegas y Granos S.A. PJR ANTARCHILE S A 21.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Limatambo S.A. PJR BAJOS DE MENA 29.12 Celfin Capital S.A. C. de B. AM Accionista Minoritario NIN BESALCO S.A. 06.12-26.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Tora Construcciones S.A. PJR BESALCO S.A. 01.12-28.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Don Víctor S.A. AM CAROZZI 12.10 Bofill Velarde, Armando AM Principado de Asturias S.A. AM CAROZZI 13.11 Accionista Minoritario NIN Invers. Alonso de Ercilla S.A. AM CAROZZI 09.11-14.11 Accionista Minoritario NIN Principado de Asturias S.A. AM CAROZZI 13.11 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones San Benito S.A. AM CEMENTO BIO 07.12-22.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Sociedad de Inversiones La Tirana Ltda. PJR BIO CEMENTO BIO 05.12-26.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Lengs Heitmann, Helga PJR BIO CGE 29.11-30.11 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Caucura Ltda. PJR CGE 29.11-30.11 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Los Acacios S.A. PJR CGE 27.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Gomez Bravo, Luis Alejandro EJ CGE 21.12 Accionista Minoritario NIN Oliver Pérez, Juan Carlos EJ CGE 04.12 Binder Demarchi, Roberto EJ Accionista Minoritario NIN CGE 28.12 Inmobiliaria Lomas de Quelen S.A. -

Acciones De Sociedades Annimas Abiertas

Superintendencia de Pensiones informa nómina de acciones que cumplen requisitos para ser consideradas en categorías generales de inversión Santiago, 05 de febrero de 2009.- La Superintendencia de Pensiones emitió la Circular N° 1587, que deroga la Circular N° 1543, relativa a los Parámetros para el cálculo de los límites de inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones y Fondos de Cesantía, la que entrará en vigencia el 10 de febrero de 2009. En la Circular, se publica la nómina de las acciones de sociedades anónimas abiertas nacionales que cumplen con los requisitos definidos por el Régimen de Inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones, para ser consideradas en las categorías generales de inversión. Cabe señalar que aquellas acciones que no cumplan con los requisitos antes señalados, podrán ser adquiridas bajo las condiciones establecidas para la categoría restringida, definida en el citado Régimen. El detalle de esta información se encuentra a continuación: ACCIONES DE SOCIEDADES ANÓNIMAS ABIERTAS 1. En virtud de lo dispuesto en el inciso sexto del artículo 45 del D.L 3.500 de 1980 y en el Régimen de Inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones las acciones elegibles en categoría general, a partir del 10 de febrero de 2009, en virtud del cumplimiento del requisito de presencia ajustada mayor o igual a 25% son las siguientes: AES GENER S.A. AGUAS ANDINAS S.A. (SERIE A) ALMENDRAL S.A. ANTARCHILE S.A. BANCO DE CHILE BANCO DE CREDITO E INVERSIONES BANCO SANTANDER CHILE BANMEDICA S.A. BANVIDA S.A. BESALCO S.A. BLANCO Y NEGRO S.A. CAP S.A. -

Monthly Andean Strategy Update Envisioning a Better Second Half in Chile

Equity Research May 13th, 2019 Monthly Andean Strategy Update Envisioning a better second half in Chile In April, the Andean region performed below LatAm markets (+0.1% in USD CREDICORP CAPITAL RESEARCH terms), with Colombia, Chile and Peru posting negative performance (-2.3%, - 1.0% and -0.7% in USD terms, respectively). The Andean region performed poorly compared to other EM markets, including Asia, Brazil and Mexico. Daniel Velandia, CFA We are moving our position in Chile to an Overweight on the back of a +(571) 3394400 ext. 1505 more favorable balance of risks relative to Colombia and Peru, but [email protected] earnings and macro dynamics have not changed. • Although we revised our 2019E GDP growth for Chile from 3.3% to 3.0%, Carolina Ratto we still expect it to grow above potential in 2H19. +(562) 2446 1768 • Market dynamics have not changed, with low activity from local and foreign [email protected] investors. The market has suffered from some overhang due to two large capital market events: Enel Am’s capital raise and Cencosud’s real estate Tomás Sanhueza IPO. This will continue until June when both operations take place. +(562) 2446 1751 • Although the short term looks soft, we see a higher downside risk in Peru [email protected] and profit-taking in Colombia, which sets a more enabling context for changing our position in Chile to an Overweight. In particular, we expect a Sebastián Gallego, CFA stronger 2H19 for Chile in earnings and macro figures. +(571) 3394400 ext. 1594 • Valuations are still discounted, even when stressing earnings growth of [email protected] relevant sectors such as Pulp, Retail and Banks. -

Estructura Topológica Del Mercado Bursátil De Chile, Período 2009-2013

ESTRUCTURA TOPOLÓGICA DEL MERCADO BURSÁTIL DE CHILE, PERÍODO 2009-2013 TOPOLOGIC STRUCTURE OF CHILEAN STOCK MARKET IN 2009-2013 Edinson Edgardo Cornejo Saavedra1 · Carola Andrea Figueroa Floresb Clasificación: Trabajo empírico - investigación Recibido: 25 de Noviembre de 2014 / Aceptado: 27 de Mayo de 2015 Resumen Este trabajo estudia cómo representar gráficamente un mercado bursátil. Con las series históricas de los precios semanales de las acciones negociadas en la Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago que registran una presencia bursátil anual mayor o igual a 80%, se diseña un mapa topológico del mercado bursátil chileno para 2009 (con base en 58 acciones), 2010 (75), 2011 (66), 2012 (69) y 2013 (65), utilizando una estructura topológica con el algoritmo de Kruskal basado en la teoría de grafos. En 2009 se observa una menor distancia entre acciones de empresas de un mismo sector económico, pero también se observan clústeres compuestos por acciones de diferentes sectores. Esto implica que, para diversificar el riesgo, no basta con invertir en acciones de diversos sectores económicos, sino que también es necesario analizar la correlación entre los retornos accionarios. En 2013, el nodo central del mercado sería la acción del Banco Santander-Chile, que se sitúa en una zona central, enlazando a un gran número de acciones pertenecientes a diversos sectores de la economía. Los mapas también evidencian una aparente inestabilidad en la estructura topológica del mercado bursátil chileno, la que se modifica entre un año y otro, exigiendo mayores actividades de monitoreo para identificar clústeres, acciones líderes y seguidoras. Se espera que el uso de una estructura topológica contribuya a una mayor comprensión de la dependencia mutua en el comportamiento de las acciones. -

MCF FYE 2007.Pdf

STATEMENTS OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES (expressed in United States dollars) DECEMBER 31, DECEMBER 31, 2007 2006 ASSETS Common stocks at fair value(cost : $54,978,780 ; 2006 $47,087,657 ) $76,949,456 $79,237,566 Receivable for investments sold 1,841,175 392,857 Cash and cash equivalents (Note 3 i ) 2,481,806 46,877 Dividends and interest receivable 358 7,188 Sundry debtors 19,064 5,373 TOTAL ASSETS 81,291,859 79,689,861 LIABILITIES Loan payable to bank (Note 4) 6,505,440 6,749,121 Payable for investments purchased (Note 6) 1,658,121 362,933 Other liabilities (Note 7) 733,802 510,830 TOTAL LIABILITIES 8,897,363 7,622,884 NET ASSETS APPLICABLE TO OUTSTANDING SHARES $72,394,496 $72,066,977 CAPITAL SHARES OF COMMON STOCK US$ 0.01 PAR VALUE Authorized 5,000,000 5,000,000 Outstanding 1,596,000 2,064,519 NET ASSETS PER SHARE $45.36 $34.91 NET ASSETS CONSIST OF: Share capital $15,960 $20,645 Paid -in capital 15,704,641 19,418,468 Accumulated net investment income 405,815 5,910,580 Accumulated net realized gains from investments and foreign currency transactions 34,355,454 14,625,425 Net unrealized appreciation on investments and foreign currencies 21,912,626 32,091,859 NET ASSETS APPLICABLE TO OUTSTANDING SHARES $72,394,496 $72,066,977 See Notes 1 to 10 to the Financial Statements. 1 SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS IN COMMON STOCKS (expressed in United States dollars) SCHEDULE BY INDUSTRY ( NOTE 3 ( d )) December 31, 2007 Percentage Percentage SHARES VALUE COST of of # $ $ Value Total Assets Investment Companies 12.21 11.56 9,401,181 4,718,550 Almendral S.A. -

Celfin Capital Andean Investor Day London –New York

Celfin Capital Andean Investor Day London –New York June 2011 This information material may include certain forward‐looking statements and projections provided by CAP S.A. (the “Company“) with respect to the financial condition, results of operations, cash flows, plans, objectives, future performance, and business of the Company. Any such statements and projections reflect various estimates and assumptions by the Company concerning anticipated results and are based on the Company’s expectations and beliefs concerning future events and, therefore, involve risks and uncertainties. Such statements and projections are neither predictions nor guarantees of future events or circumstances, which may never occur, and actual results may differ materially from those contemplated (expressed or implied) by such forward‐ looking statements and projections. No representations or warranties are made by the Company or any of its affiliates as to the accuracy of any such statements or projections. Whether or not any such forward looking‐statements or projections are in fact achieved will depend upon future events, some of which are not within the control of the Company. Accordingly, the recipient of this material should not place undue reliance on such statements. Any such statements and projections speak only as of the date on which they are made, and the Company does not undertake any obligation, and expressly disclaims any obligation, to update or revise any such statements or projections as a result of new information, future events, or otherwise