The Effects of Audit Firm Rotation: an Event Study in Chile Antonio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bases De Promoción }

{ BASES DE PROMOCIÓN } Bases de Promoción “Recarga Salcobrand Junio” En Santiago de Chile, a 21 de abril de 2015, comparece ENTEL COMERCIAL S.A., en adelante “Entel”, RUT N° 76.479.460-5, representada por don José Luis Poch Piretta, cédula de identidad N° 7.010.335-4, ambos domi- ciliados en Avenida Costanera Sur Río Mapocho N° 2760, Torre C, piso N° 20, comuna de Las Condes, ciudad de Santiago, quien establece las siguientes Bases de la Promoción denominada “Recarga Salcobrand Junio”. PRIMERO: Antecedentes y vigencia. Entel realizará entre el 01 y el 30 de Junio de 2016, ambas fechas inclusive, una promoción denominada “Recarga Salcobrand Mayo”, en adelante la “Promoción”. SEGUNDO: Mecánica de la Promoción. Podrán participar en esta Promoción las personas naturales residentes en Chile que: (1) Sean clientes de prepago de Entel, esto es, aquellos clientes que deben comprar recargas Entel para utilizar en su equipo móvil y que no tienen asociados cobros periódicos; o, (2) Sean clientes de Entel que han contratado un plan Cuenta Controlada de telefonía móvil y que una vez utiliza- do su saldo de cuenta controlada, deben comprar recargas Entel para utilizar en su equipo móvil. En adelante, se podrá denominar a quienes cumplan con lo expuesto en alguno de los dos números anteriores como “Clientes de Recarga”. Para participar de esta Promoción los Clientes de Recarga deberán adquirir, durante la vigencia de la Promoción, recargas Entel para utilizar en su equipo móvil, en los locales de Salcobrand adheridos a la Promoción a nivel nacional, los que se encuentran detallados en el Anexo N° 1 de las presentes bases. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

Draft version :: do not distribute Corporate Presentation November, 2015 Disclaimer Statements made in this presentation related to VSPT’s future performance or financial results are “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of section 27ª of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended, which are not statements of fact and involve uncertainties that could cause actual performance or results to materially differ. Forward looking statements include, without limitation, any statement that may predict, forecast, indicate or imply future results, performance or achievements, and may contain words like “believe”, “anticipate”, “expect”, “envisages”, “will likely result” or any other words or phrases of similar meaning. Our forward looking statements are not guarantees of future performance, and our actual results or other developments may differ materially from the expectations expressed in the forward looking statements. As for forward - looking statements that relate to future financial results and other projections, actual results will be different due to the inherent uncertainty of the estimates, forecasts and projections. Because of these risks and uncertainties, potential investors should not rely on these forward-looking statements. Our independent public accountants have not examined or compiled the forward-looking statements and, accordingly, do not provide any assurance with respect to such statements. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is or will be made or given by us or any of our affiliates or directors or any other person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this presentation and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted for any such information or opinions. -

Siglo Xxi Fondo De Inversión

SIGLO XXI FONDO DE INVERSIÓN Estados Financieros al 31 de diciembre de 2020 y 2019 y por los ejercicios terminados en esas fechas. (Con el Informe de los Auditores Independientes) SIGLO XXI FONDO DE INVERSIÓN CONTENIDO Informe de los Auditores Independientes Estados de Situación Financiera Estados de Resultados Integrales Estados de Cambios en el Patrimonio Neto Estados de Flujos de Efectivo Notas a los Estados Financieros Estados Complementarios $ : Cifras expresadas en pesos chilenos M$: Cifras expresadas en miles de pesos chilenos UF : Cifras expresadas en unidades de fomento INFORME DE LOS AUDITORES INDEPENDIENTES Señores Aportantes SIGLO XXI FONDO DE INVERSIÓN Hemos efectuado una auditoría a los estados financieros adjuntos de Siglo XXI Fondo de Inversión, que comprenden los estados de situación financiera al 31 de diciembre de 2020 y 2019 y los correspondientes estados de resultados integrales, de cambios en el patrimonio neto y de flujos de efectivo por los años terminados en esas fechas y las correspondientes notas a los estados financieros. Responsabilidad de la Administración por los Estados Financieros La Administración del Fondo es responsable por la preparación y presentación razonable de estos estados financieros de acuerdo con Normas Internacionales de Información Financiera (NIIF) emitidas por el International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB”). Esta responsabilidad incluye el diseño, implementación y mantención de un control interno pertinente para la preparación y presentación razonable de estados financieros que estén exentos de representaciones incorrectas significativas, ya sea debido a fraude o error. Responsabilidad del Auditor Nuestra responsabilidad consiste en expresar una opinión sobre estados financieros a base de nuestra auditoría. Efectuamos nuestra auditoría de acuerdo con normas de auditoría generalmente aceptadas en Chile. -

Empresas Copec S.A. Consolidated Financial

EMPRESAS COPEC S.A. CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2018 IFRS - International Financial Reporting Standards IAS - International Accounting Standards NIFCH - Chilean Financial Reporting Standards IFRIC - International Financial Reporting Interpretations Committee US$ - United States dollars ThUS$ - Thousands of US dollars MUS$ - Millions of US dollars MCh$ - Millions of Chilean Pesos COP$ - Colombian pesos S./ - Peruvian nuevo sol WorldReginfo - d6a34cd4-9970-4f3e-9bfb-af0f71482286 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT Santiago, March 8, 2019 Dear Shareholders and Directors Empresas Copec S.A. We have audited the accompanying consolidated financial statements of Empresas Copec S.A. and affiliates, which comprise a consolidated statement of financial position as of December 31, 2018 and 2017, the corresponding consolidated statements of income by function, consolidated comprehensive income, consolidated changes in equity and consolidated cash flow for the years ending on these dates, and the corresponding notes to the consolidated financial statements. Management's responsibility for the consolidated financial statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these consolidated financial statements in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). This responsibility includes the design, implementation and maintenance of relevant internal controls for the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether -

The Santiago Exchange Indices Methodology Consultation

The Santiago Exchange Indices Methodology Consultation SANTIAGO, APRIL 2, 2018: In August 2016, the Santiago Exchange (the “Exchange”) and S&P Dow Jones Indices (“S&P DJI”) signed an Index Operation and License Agreement. The Exchange’s partnership with S&P DJI, the world’s leading provider of index-based concepts, data and research, includes the adoption of international index methodology standards and the integration of operational processes and business strategies and enhances the visibility, governance, and transparency of the existing indices. The agreement also enables the development, licensing, distribution and management of current and future indices which will be designed to serve as innovative and practical tools for local and global investors. The new and existing Santiago Exchange indices will be co-branded under the “S&P/CLX” name (the “Indices”) that can be used to underlie liquid financial products, expanding the breadth and depth of the Chilean capital market. As part of this transition, S&P DJI and the Exchange are conducting a consultation with members of the investment community on potential changes to the following Santiago Exchange indices to ensure that they continue to meet their objectives and are aligned with the needs of local and international market participants. • Indice General de Precios y Acciones (“IGPA”) • IGPA Large, IGPA Mid, and IGPA Small (collectively “IGPA Size Indices”) • Indice de Precios Selectivo de Acciones (“IPSA”) IGPA The IGPA is designed to serve as a broad country benchmark of the Chilean market. Based on a review of the index’s methodology and existing data, and to ensure that the index continues to satisfy its objective, S&P DJI and the Exchange are proposing to increase the minimum bursatility presence1 required for index eligibility. -

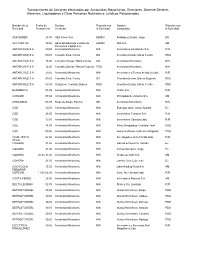

Transacciones De Acciones Efectuadas Por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General

Transacciones de Acciones efectuadas por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General, Nombre de la Fecha de Nombre Relación con Nombre Relación con Sociedad Transacción Vendedor la Sociedad Comprador la Sociedad ANDACOR 18.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Leatherbee Grant, Michael DG ANDACOR 18.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Leatherbee Grant, Peter James AM ANTARCHILE S A 07.01 Inversiones Peñuelas Limitada PJR Accionista Minoritario NIN ANTARCHILE S A 07.01 Inversiones Peñuelas Limitada PJR Rentas ASM Limitada U ANTARCHILE S A 07.01 Inversiones Peñuelas Limitada PJR Rentas AEB Limitada U BAJOS DE MENA 18.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Celfin Capital S.A. C. de B. AM BAJOS DE MENA 07.01-08.01 Celfin Capital S.A. C. de B. AM Accionista Minoritario NIN BAJOS DE MENA 11.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Viviani Canello, Víctor DG BESALCO S.A. 15.01-24.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Don Víctor S.A. AM CAP S.A. 28.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN De Andraca Adriasola, Daniela PDG CAROZZI 14.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Principado de Asturias S.A. AM CEMENTO BIO 23.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Sturms Stein, Cristian DG BIO COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Agricola e Inmobiliaria La Maison S.A. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Santa Victoria Ltda. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Santa Marta Ltda. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Tisil Ltda. PJR COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Guallatiri Ltda. AM COVADONGA 25.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones San Pablo S.A. PJR CURAUMA 10.01 Accionista Minoritario NIN Soc. -

Viña Concha Y Toro S.A. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on April 30, 2013 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 20-F (Mark One) REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ; ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report For the transition period from to Commission File number 001-13358 Viña Concha y Toro S.A. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Concha y Toro Winery Inc. (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Republic of Chile (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Casilla 213 Nueva Tajamar 481 Torre Norte, Piso 15 Santiago, Chile (562) 2476-5000 (Address and telephone number of principal executive offices) Matías Rojas (562) 2476-5644 [email protected] Nueva Tajamar 481 Torre Norte, Piso 15 Santiago, Chile (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered American Depositary Shares (“ADS”), each representing 20 Shares of common stock New York Stock Exchange Shares of common stock (“Shares”or “Common Stock”), without nominal (par) value, of Viña Concha y Toro S.A. -

Gobierno Corporativo: Ranking De Empresas Chilenas Con Mayor Transacción En La Bolsa De Valores1 Revista Lasallista De Investigación, Vol

Revista Lasallista de Investigación ISSN: 1794-4449 Corporación Universitaria Lasallista Severino-González, Pedro; Acuña-Moraga, Omar Gobierno corporativo: ranking de empresas chilenas con mayor transacción en la bolsa de valores1 Revista Lasallista de Investigación, vol. 16, núm. 1, 2019, pp. 103-114 Corporación Universitaria Lasallista DOI: 10.22507/rli.v16n1a3 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=69563162007 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Artículo original / Original article / Artigo original DOI: 10.22507/rli.v16n1a3 Gobierno corporativo: ranking de empresas chilenas con mayor transacción en la bolsa de valores1 Pedro Severino-González2, Omar Acuña-Moraga3 Resumen se puede mencionar el cambio significativo en la posición de AntarChile S. A. y Introducción. Debido a los conflictos de SalfaCorp S. A. Conclusión. El bajo interés, problemas de agencia, prácticas desempeño generalizado es debido a la deshonestas y falta a la responsabilidad rigurosidad de la nueva norma, provocando social, en todo el mundo se han diseñado una disminución de 72% a 39% de normas, estándares y reglamentos que cumplimiento. pretenden resguardar los intereses de cada stakeholders, como consecuencia de una Palabras clave: gobierno corporativo, situación crítica que afecta la relación entre norma, gestión, economía de la empresa, el principal y el agente. Objetivo. Esta Responsabilidad Social Empresarial. investigación tiene como objetivo analizar las prácticas de gobierno corporativo de empresas chilenas que forman parte del Corporate governance: ranking IPSA4. -

Nómina De Acciones

NÓMINA DE ACCIONES NÓMINA DE ACIONES QUE CUMPLEN REQUISITOS PARA SER CONSIDERADAS EN CATEGORÍAS GENERALES DE INVERSIÓN REPORTE TRIMESTRAL NÓMINA DE ACCIONES QUE CUMPLEN REQUISITOS PARA SER CONSIDERADAS EN CATEGORÍAS GENERALES DE INVERSIÓN La Superintendencia de Pensiones emitió la Circular N° 2.026 que deroga la Circular N° 2.010, relativa a los Parámetros para el cálculo de los límites de inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones y Fondos de Cesantía, la que entrará en vigencia el 20 de marzo de 2018. En la Circular, se publica la nómina de las acciones de sociedades anónimas abiertas nacionales que cumplen con los requisitos definidos por el Régimen de Inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones, para ser consideradas en las categorías generales de inversión. Cabe señalar que aquellas acciones que no cumplan con los requisitos antes señalados, podrán ser adquiridas bajo las condiciones establecidas para la categoría restringida, definida en el citado Régimen. El detalle de esta información se encuentra a continuación: ACCIONES DE SOCIEDADES ANÓNIMAS ABIERTAS 1. De acuerdo a lo dispuesto en el inciso sexto del artículo 45 del D.L 3.500 de 1980 y en el Régimen de Inversión de los Fondos de Pensiones las acciones elegibles en categoría general, tanto por instrumento como por emisor, a partir del 20 de marzo de 2018, en virtud del cumplimiento del requisito de presencia ajustada mayor o igual a 25% o contar con un Market Maker en los términos y condiciones establecidos en la Normativa vigente, son las siguientes: RAZÓN SOCIAL NEMOTÉCNICO SERIE AES GENER S.A. AESGENER ÚNICA AGUAS ANDINAS S.A. -

Articles-15829 Recurso 1.Pdf

Transacciones de Acciones efectuadas por Accionistas Mayoritarios, Directores, Gerente General, Gerentes, Liquidadores y Otras Personas Naturales o Jurídicas Relacionadas Nombre de la Fecha de Nombre Relación con Nombre Relación con Sociedad Transacción Vendedor la Sociedad Comprador la Sociedad AES GENER 28.05 AES Gener S.A. EMISO Rodríguez Grossi, Jorge DG AFP CAPITAL 30.05 Administradora de Fondos de EMISO ING S.A. AM Pensiones Capital S.A. ANTARCHILE S A 29.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Limatambo S.A. PJR ANTARCHILE S A 09.05 Croxatto Silva, Carlos DG Croxatto Ortuzar, María Cecilia PDG ANTARCHILE S A 16.05 Croxatto Ortuzar, María Cecilia DG Accionista Minoritario NIN ANTARCHILE S A 16.05 Croxatto Ortuzar, Blanca Eugenia PDG Accionista Minoritario NIN ANTARCHILE S A 29.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones y Rentas Ancabela Ltda. PJR ANTARCHILE S A 09.05 Croxatto Silva, Carlos DG Croxatto Ortuzar, Blanca Eugenia PDG ANTARCHILE S A 09.05 Ortuzar de Croxatto, Blanca PDG Croxatto Ortuzar, María Cecilia PDG BANMEDICA 05.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Green S.A. PJR CAROZZI 07.04 Accionista Minoritario NIN Principado de Asturias S.A. AM CENCOSUD 08.05 Rivas de Diego, Patricio GE Accionista Minoritario NIN CGE 20.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Estrougo Ortiz, Jaime Azarias EJ CGE 28.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Tunquen S.A. PJR CGE 13.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inversiones Caucura Ltda. PJR CGE 14.03 Accionista Minoritario NIN Pérez Respaldiza, Cristobal José PDG CGE 09.05 Accionista Minoritario NIN Heinsen Widow, Gabrielle Margarita PDG CLUB HIPICO 02.06 Accionista Minoritario NIN Inv. Ongolmo de la Florida Ltda. -

Cotización En Bolsa Bonos Al Portador Desmaterializados, De Viña Concha Y Toro S.A

Santiago, 31 de julio de 2019 REF.: Cotización en Bolsa Bonos al Portador Desmaterializados, de Viña Concha y Toro S.A. ________________________________ COMUNICACIÓN INTERNA N°14.860 Señor Corredor: Tengo el agrado de informar a usted, que a partir de mañana jueves 1 de agosto de 2019, se podrá realizar oficialmente en la Bolsa de Santiago la cotización, transacción y liquidación de las siguientes series de Bonos al Portador Desmaterializados emitidos por Viña Concha y Toro S.A.: Serie/Código Bursátil BCTOR-R BCTOR-S BCTOR-T Estos instrumentos fueron inscritos en el Registro Público de Valores de la Comisión para el Mercado Financiero bajo las líneas Nº840 y N°931, con fecha 12 de octubre de 2016 y 20 de marzo de 2019 respectivamente. Cabe hacer presente, que estos bonos se encuentran acogidos al beneficio tributario establecido en el artículo 104 y a su vez a lo dispuesto en el Nº8 del artículo 74, ambos de la Ley de Impuesto a la Renta. Se adjunta a la presente comunicación copia del resumen de las características de estos bonos, contenidas en el prospecto de emisión y certificado de registro de dicho instrumento en la referida Comisión. Para mayor información, el prospecto de emisión de este instrumento se encuentra disponible en los terminales de consulta SEBRA HT, específicamente en “Observaciones” de la consulta (RIRF) Resumen de un Bono. Sin otro particular, saluda atentamente a usted, BOLSA DE COMERCIO DE SANTIAGO, BOLSA DE VALORES Juan C. Ponce Hidalgo GERENTE DE SERVICIOS BURSÁTILES Adj.: lo indicado DS L a B o l s a 64, S a n t i a g o , C h i l e . -

Inversionistas Chilenos En Argentina

MINISTERIO DE RELACIONES EXTERIORES - CHILE Dirección General de Relaciones Económicas Internacionales Dirección de Asuntos Económicos Bilaterales Departamento de Inversiones en el Extranjero EMPRESAS CHILENAS CON INVERSIONES EN EL EXTERIOR, SEGUN PAGINAS WEB DE CADA EMPRESA INVERSIONISTA EMPRESAS CHILENAS CON INVERSIONES DIRECTAS EN : ARGENTINA NOMBRE EMPRESA DIRECCION PÁGINA WEB 1 AGENCIAS UNIVERSALES S.A. (AGUNSA) http://www.agunsa.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=45&Itemid=46&pais=true 2 ANASAC http://www.anasac.cl/anasac/empresa/filiales 3 AGROBERRIES http://www.agroberries.cl/company.html 4 ALUSA S.A. http://www.alusa.cl/inicio.html 5 ATENTUS S.A http://www.atentus.com/ 6 AQB S.A. http://www.aqbargentina.com.ar/historia.php 7 CELULOSA ARAUCO Y CONSTITUCION (CELCO) http://www.arauco.cl/default.asp 8 CEM (EX INDUGAS) http://www.cembrass.com.ar/esp/main.html 9 CENCOSUD S.A. http://www.cencosud.cl/unidades_easy_argentina.htm 10 CESMEC http://www.cesmec.cl/nueva/acerca/index.act 11 CHILE FILMS http://www.cinecolor.com.ar/ 12 CIA. GENERAL DE ELECTRICIDAD - CGE http://www.cge.cl/sectorelectrico/Paginas/SectorElectrico.aspx 13 CIA. SUDAMERICANA DE VAPORES http://www.csav.com/csav/abusoffices.nsf/frmfilter?OpenForm&Seq=4#a1 14 CIDEF http://www.cidef.com.ar/ 15 COLCHONES ROSEN http://www.rosenthestore.com/home.html 16 COASIN http://www.coasin.com/fileadmin/Template/img/Principal/Minternacional.swf 17 CORESA S.A. http://www.coresa.com.ar/ 18 CORPORA TRES MONTES S.A. http://www.tmluc.cl/ 19 EMBOTELLADORA ANDINA S.A. http://www.cocacola-edasa.com.ar/edasa/ 20 EMBOTELLADORA COCA-COLA POLAR S.A.