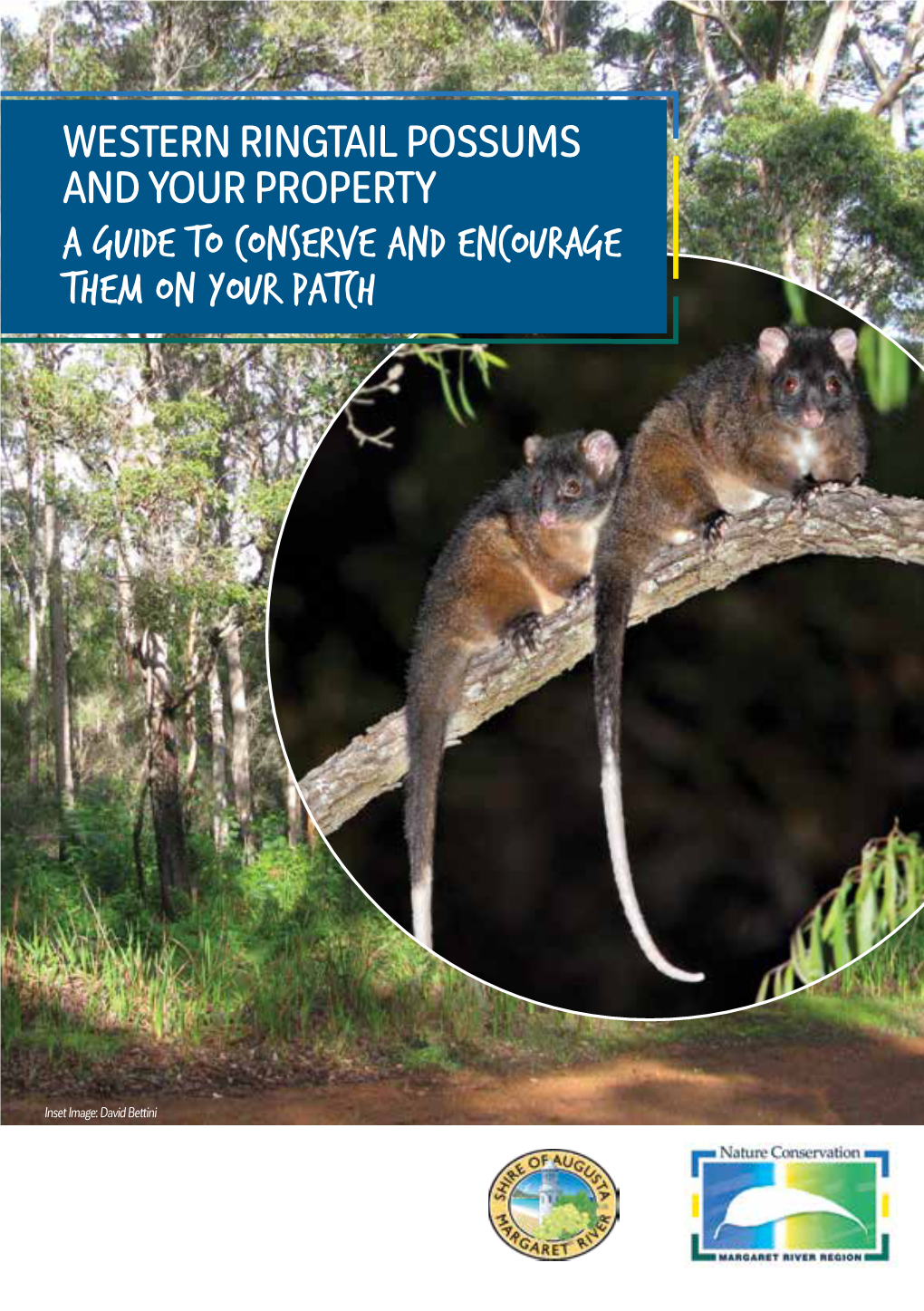

WESTERN RINGTAIL POSSUMS and YOUR PROPERTY a Guide to Conserve and Encourage Them on Your Patch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus Occidentalis) Recovery Plan

Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) Recovery Plan Wildlife Management Program No. 58 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife October 2014 Wildlife Management Program No. 58 Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) Recovery Plan October 2014 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983 Foreword Recovery plans are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Parks and Wildlife Policy Statements Nos. 44 and 50 (CALM 1992, 1994), and the Australian Government Department of the Environment’s Recovery Planning Compliance Checklist for Legislative and Process Requirements (DEWHA 2008). Recovery plans outline the recovery actions that are needed to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. Recovery plans are a partnership between the Department of the Environment and the Department of Parks and Wildlife. The Department of Parks and Wildlife acknowledges the role of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and the Department of the Environment in guiding the implementation of this recovery plan. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds necessary to implement actions are subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. This recovery plan was approved by the Department of Parks and Wildlife, Western Australia. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community, and the completion of recovery actions. Information in this recovery plan was accurate as of October 2014. -

Husbandry Guidelines for Common Ringtail Possums, Pseudocheirus Peregrinus Mammalia: Pseudocheiridae

32325/01 Casey Poolman E0190918 Husbandry guidelines for Common Ringtail Possums, Pseudocheirus peregrinus Mammalia: Pseudocheiridae Ault Ringtail Possum Image: Casey Poolman Author: Casey Poolman Date of preparation: 7/11/2017 Open Colleges, Course name and number: ACM30310 Certificate III in Captive Animals Trainer: Chris Hosking Husbandry guidelines for Pseudocheirus peregrinus 1 32325/01 Casey Poolman E0190918 Author contact details [email protected] Disclaimer Please note that these husbandry guidelines are student material, created as part of student assessment for Open Colleges ACM30310 Certificate III in Captive Animals. While care has been taken by students to compile accurate and complete material at the time of creation, all information contained should be interpreted with care. No responsibility is assumed for any loss or damage resulting from using these guidelines. Husbandry guidelines are evolving documents that need to be updated regularly as more information becomes available and industry knowledge about animal welfare and care is extended. Husbandry guidelines for Pseudocheirus peregrinus 2 32325/01 Casey Poolman E0190918 Workplace Health and Safety risks warning Ringtail Possums are not an aggressive possum and will mostly try to freeze or hide when handled, however they can and do bite, which can be deep and penetrating. When handling possums always be careful not to get bitten, do not put your hands around its mouth. You should always use two hands and be firm but gentle. Adult Ringtail Possums should be gripped by the back of the neck and around the shoulders with one hand and around the base of the tail with the other. This should allow you to control the animal without hurting it and reduces the risk of you being bitten or scratched. -

Yellow Bellied Glider

Husbandry Manual for the Yellow-Bellied Glider Petaurus australis [Mammalia / Petauridae] Liana Carroll December 2005 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond 1068 Certificate III Captive Animals Lecturer: Graeme Phipps TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 5 2 TAXONOMY ...................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 NOMENCLATURE .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 SUBSPECIES .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.3 RECENT SYNONYMS ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.4 OTHER COMMON NAMES ............................................................................................................. 6 3 NATURAL HISTORY ....................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 MORPHOMETRICS ......................................................................................................................... 8 3.1.1 Mass And Basic Body Measurements ..................................................................................... 8 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism ................................................................................................................ -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Evergreen Trees Agonis Flexuosa

Evergreen Trees Agonis flexuosa – Peppermint Willow Graceful willow-like evergreen tree (but without the willows voracious root system) with reddish-brown, deeply furrowed bark to 25’-30’. New leaves and twigs have an attractive reddish cast; clustered small white flowers and brownish fruits are not particularly ornamental. Casaurina stricta – Beefwood Pendulous gray branches; resembles a pine somewhat; tolerates drought, heat, wind, fog. Growth to 20’- 30’. Cinnamomum camphora - Camphor Evergreen trees to 40 feet, with 20-foot spread.. In winter foliage is a shiny yellow green. In early spring new foliage may be pink, red or bronze, depending on tree. Unusually strong structure. Clusters of tiny, fragrant yellow flowers in profusion in May. Geijera parviflora- Australian Willow Evergreen trees with graceful, fine-textured leaves, to 30 feet, 20 feet wide. Main branches weep up and out; little branches hang down. Much of the grace of a willow, much of the toughness of eucalyptus, moderate growth and deep non-invasive roots. Laurus nobilis – Grecian Laurel Slow growth 12-40’. Natural habit is compact, broad-based, often multi-stemmed, gradually tapering cone. Leaves lethery, aromatic. Clusters of small yellow flowers followed by black or purple berries. Magnolia Grandiflora – ‘Little Gem’- Dwarf Southern Magnolia Small tree to 20’ in height. Showy white flowers in the summer. Green glossy leaves. Maytenous boaria - Mayten Evergreen tree with slow to moderate growth to an eventual 30-50 feet, with a 15-foot spread, with long and pendulous branchlets hanging down from branches, giving tree a graceful look. Habit and leaves somewhat like a small scale weeping willow. -

Biparental Care and Obligate Monogamy in the Rock-Haunting Possum, Petropseudes Dahli, from Tropical Australia

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2000, 59, 1001–1008 doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1392, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Biparental care and obligate monogamy in the rock-haunting possum, Petropseudes dahli, from tropical Australia MYFANWY J. RUNCIE CRC for Sustainable Development of Tropical Savannas, Northern Territory University (Received 10 May 1999; initial acceptance 9 June 1999; final acceptance 30 December 1999; MS. number: 6222R) Monogamy is rare among mammals, including marsupials. I studied the social organization of the little-known rock-haunting possum in Kakadu National Park in Northern Australia. Preliminary field observations revealed that the majority of possums live in cohesive groups consisting of a female–male pair and young, suggesting a monogamous mating system. I used radiotracking to determine home range patterns, and observations to measure the degree of symmetry between the sexes in maintaining the pair bond and initiating changes in group activity. I also measured the extent of maternal and paternal indirect and direct care. Nocturnal observations and radiotelemetric data from 3 years showed that six possum groups maintained nonoverlapping home ranges with long-term consorts and young sharing dens. Males contributed more than females to maintaining the pair bond but they contributed equally to parental care. For the first time, the parental behaviours of bridge formation, embracing, marshalling of young, sentinel behaviour and tail beating are reported in a marsupial. Males participated to a high degree in maintaining relationships with one mate and their offspring. Collectively, these results suggest that the mating system of this wild population of rock-haunting possums is obligate social monogamy. -

Australian Marsupial Species Identification

G Model FSIGSS-793; No. of Pages 2 Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/FSIGSS Australian marsupial species identification a, b,e c,d d d Linzi Wilson-Wilde *, Janette Norman , James Robertson , Stephen Sarre , Arthur Georges a ANZPAA National Institute of Forensic Science, Victoria, Australia b Museum Victoria, Victoria, Australia c Australian Federal Police, Australian Capital Territory, Australia d University of Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia e Melbourne University, Victoria, Australia A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Wildlife crime, the illegal trade in animals and animal products, is a growing concern and valued at up to Received 10 October 2011 US$20 billion globally per year. Australia is often targeted for its unique fauna, proximity to South East Accepted 10 October 2011 Asia and porous borders. Marsupials of the order Diprotodontia (including koala, wombats, possums, gliders, kangaroos) are sometimes targeted for their skin, meat and for the pet trade. However, species Keywords: identification for forensic purposes must be underpinned by robust phylogenetic information. A Species identification Diprotodont phylogeny containing a large number of taxa generated from nuclear and mitochondrial Forensic data has not yet been constructed. Here the mitochondrial (COI and ND2) and nuclear markers (APOB, DNA IRBP and GAPD) are combined to create a more robust phylogeny to underpin a species identification COI Barcoding method for the marsupial order Diprotodontia. Mitochondrial markers were combined with nuclear Diprotodontia markers to amplify 27 genera of Diprotodontia. -

The Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus Occidentalis)

A major road and an artificial waterway are barriers to the rapidly declining western ringtail possum, Pseudocheirus occidentalis Kaori Yokochi BSc. (Hons.) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Animal Biology Faculty of Science October 2015 Abstract Roads are known to pose negative impacts on wildlife by causing direct mortality, habitat destruction and habitat fragmentation. Other kinds of artificial linear structures, such as railways, powerline corridors and artificial waterways, have the potential to cause similar negative impacts. However, their impacts have been rarely studied, especially on arboreal species even though these animals are thought to be highly vulnerable to the effects of habitat fragmentation due to their fidelity to canopies. In this thesis, I studied the effects of a major road and an artificial waterway on movements and genetics of an endangered arboreal species, the western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis). Despite their endangered status and recent dramatic decline, not a lot is known about this species mainly because of the difficulties in capturing them. Using a specially designed dart gun, I captured and radio tracked possums over three consecutive years to study their movement and survival along Caves Road and an artificial waterway near Busselton, Western Australia. I studied the home ranges, dispersal pattern, genetic diversity and survival, and performed population viability analyses on a population with one of the highest known densities of P. occidentalis. I also carried out simulations to investigate the consequences of removing the main causes of mortality in radio collared adults, fox predation and road mortality, in order to identify effective management options. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Cercartetus Lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae)

MAMMALIAN SPECIES 842:1–8 Cercartetus lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae) JAMIE M. HARRIS School of Environmental Science and Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, New South Wales, 2480, Australia; [email protected] Abstract: Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) is a burramyid commonly called the little pygmy-possum. It is 1 of 4 species in the genus Cercartetus, which together with Burramys parvus form the marsupial family Burramyidae. This Lilliputian possum has a disjunct distribution, occurring on mainland Australia, Kangaroo Island, and in Tasmania. Mallee and heath communities are occupied in Victoria and South Australia, but in Tasmania it is found mainly in dry and wet sclerophyll forests. It is known from at least 18 fossil sites and the distribution of these reveal a significant contraction in geographic range since the late Pleistocene. Currently, this species is not listed as threatened in any state jurisdictions in Australia, but monitoring is required in order to more accurately define its conservation status. DOI: 10.1644/842.1. Key words: Australia, burramyid, hibernator, little pygmy-possum, pygmy-possum, Tasmania, Victoria mallee Published 25 September 2009 by the American Society of Mammalogists Synonymy completed 2 April 2008 www.mammalogy.org Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) Little Pygmy-possum Dromicia lepida Thomas, 1888:142. Type locality ‘‘Tasma- nia.’’ E[udromicia](Dromiciola) lepida: Matschie, 1916:260. Name combination. Eudromicia lepida Iredale and Troughton, 1934:23. Type locality ‘‘Tasmania.’’ Cercartetus lepidus: Wakefield, 1963:99. First use of current name combination. CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Order Diprotodontia, suborder Phalangiformes, superfamily Phalangeroidea, family Burra- myidae (Kirsch 1968). No subspecies for Cercartetus lepidus are currently recognized. -

Identification of Myrtle Rust (Uredo Rangelii)

Identification of Myrtle Rust (Uredo rangelii) 6 October 2010 Hosts Myrtle Rust has been found on the NSW Central Coast on eleven species of cultivated native plants: • Agonis flexuosa (willow myrtle) cv. 'Afterdark' and cv. 'Burgundy' • Tristania neriifolia (water gum) • Syncarpia glomulifera (turpentine) • Callistemon viminalis (bottle brush) • Leptospermum rotundifolium (tea tree) • Syzygium leumannii x Syzygium wilsonii (lilly pilly) • Syzygium jambos (rose apple) • Syzygium australe cv. 'Meridian Midget' • Metrosideros collina cv. Dwarf • Austromyrtus inophloia cv. 'Aurora' and 'Blushing Beauty' (renamed to Gossia inophloia) • Rhodamnia rubescens (scrub turpentine) Other known hosts include Myrtus communis (common myrtle). At present, severe infestation has only been observed on A. flexuosa (willow myrtle) cv. 'Afterdark', Tristania neriifolia (water gum) and Austromyrtus inophloia cv. 'Aurora' and 'Blushing Beauty'. Spread Rust spores travel very long distances on the wind and may infect stands of susceptible plants many kilometres from the original infestation. Rust spores are also gathered and spread by bees. These are natural means of spread that are difficult to control. Humans can also easily spread Myrtle Rust in infested plant material including cut flowers and nursery stock, on clothing and dirty equipment including containers and pruning shears, and on contaminated timber products. Always practise good hygiene when working with native plants and general nursery stock. Images See the following pages. Reporting To report suspect cases of Myrtle Rust, please call the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881. © State of New South Wales through Department of Industry and Investment (Industry & Investment NSW) 2010. You may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute Industry & Investment NSW as the owner. -

Peppermint Tree Scientific Name: Agonis Flexuosa

Peppermint Tree Scientific name: Agonis flexuosa Aboriginal name: Wonnil (Noongar) Plant habit Bark Flower bud Flower About ... Family MYRTACEAE Also called the ‘Willow Myrtle’, this species is native to Climate Temperate the south-west of Western Australia. Habitat Coastal and bushland areas close to the This species is highly adaptable to a range of climates coast and lower Swan Estuary in sandy/ and soils. Because of this, it is often planted along limestone soils verges and in parkland areas. It is a common street tree in many Perth suburbs including Peppermint Form Tree Grove which is named after the tree. Fibrous, rough grey bark Its flowers look similar to the native tea tree. Large, gnarled trunk Peppermint Trees are named after the peppermint Height: 10 – 15 m odour of the leaves when crushed. Width: 6 m Mature trees provide hollows that are used by birds Foliage Weeping foliage and possums for nesting. Mid-to-bright green Long, slender leaves Evergreen Flower Kambarang to Bunuru (Spring and Summer) Aboriginal Uses Sprays of several small white flowers • Leaves were used for smoking and healing Width: 1 cm Flowers have five petals • Oil used to rub on cuts and sores Insect attracting ALGAE BUSTER Developed by SERCUL for use with the Bush Tucker Education Program. Used as food Used as medicine Used as resources Local to SW WA Caution: Do not prepare bush tucker food without having been shown by Indigenous or experienced persons. PHOSPHORUS www.sercul.org.au/our-projects/ AWARENESS PROJECT bushtucker/ Some bush tucker if eaten in large quantities or not prepared correctly can cause illness..