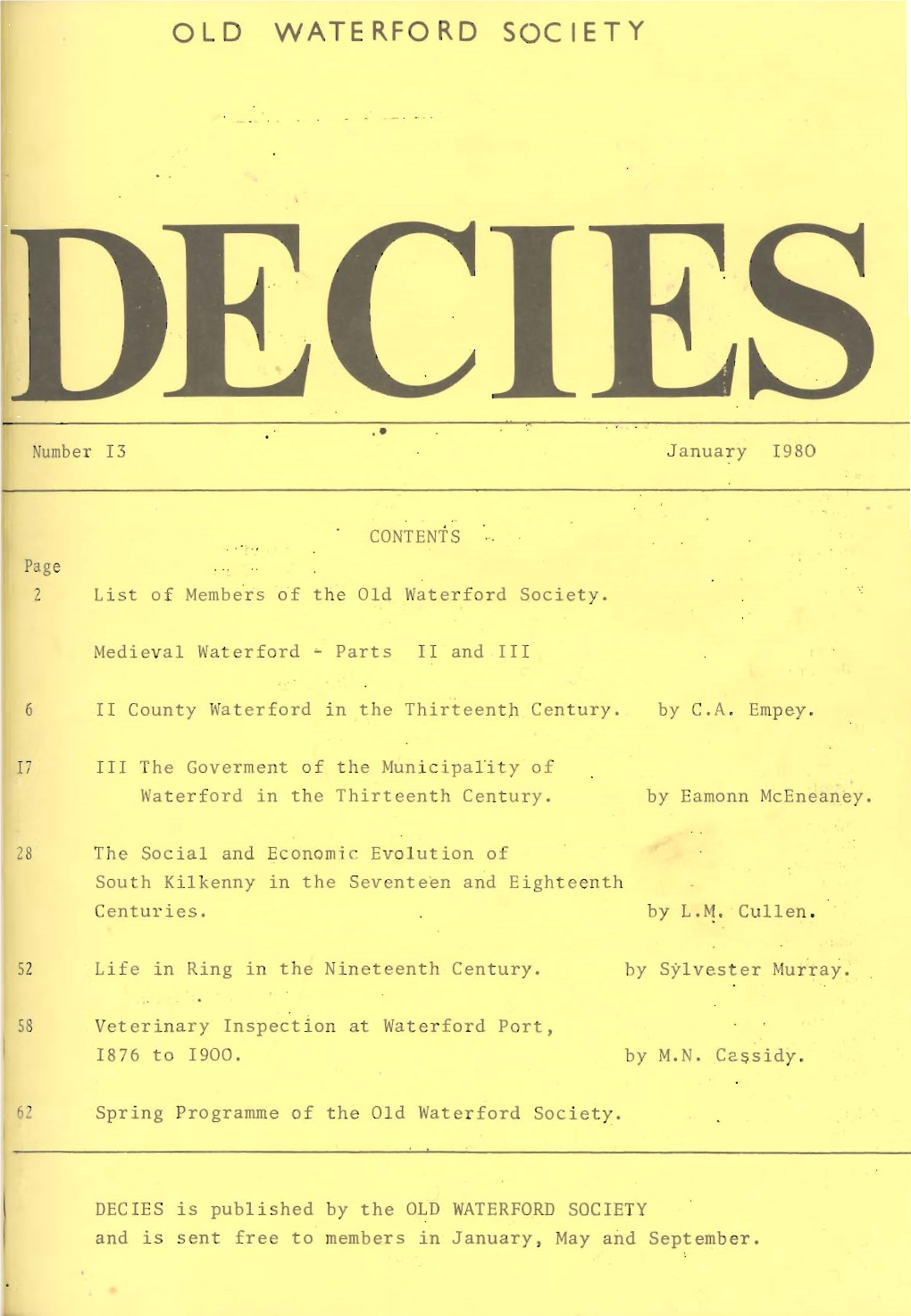

Old Waterford Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prior-Wandesforde Papers (Additional)

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 173 Prior-Wandesforde Papers (Additional) (SEE ALSO COLLECTION LISTS No. 52 & 101) (MSS 48,342-48,354) A small collection of estate and colliery papers of the Prior-Wandesforde family of Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny, 1804-1969. Compiled by Owen McGee, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 I. The Castlecomer Colliery ............................................................................................. 5 I.i. Title deeds to the mines (1819-1869)........................................................................ 5 I.ii. Business accounts for the Castlecomer mines (1818-1897)..................................... 8 I.iii. Castlecomer Collieries Ltd. (1903-1969).............................................................. 10 I.iii.1 Business correspondence (1900-1928)............................................................ 10 I.iii.2 General accounts (1920-1963) ........................................................................ 12 I.iii.3 Company stock and production accounts (1937-1966)................................... 14 I.iii.4 Staff-pay accounts (1940-1966)...................................................................... 15 I.iii.5 Accident insurance claims (1948-1967).......................................................... 16 I.iii.6 Employer and Trade Union related material (1949-1959)............................. -

A Brief History of the Purcells of Ireland

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One: The Purcells as lieutenants and kinsmen of the Butler Family of Ormond – page 4 Part Two: The history of the senior line, the Purcells of Loughmoe, as an illustration of the evolving fortunes of the family over the centuries – page 9 1100s to 1300s – page 9 1400s and 1500s – page 25 1600s and 1700s – page 33 Part Three: An account of several junior lines of the Purcells of Loughmoe – page 43 The Purcells of Fennel and Ballyfoyle – page 44 The Purcells of Foulksrath – page 47 The Purcells of the Garrans – page 49 The Purcells of Conahy – page 50 The final collapse of the Purcells – page 54 APPENDIX I: THE TITLES OF BARON HELD BY THE PURCELLS – page 68 APPENDIX II: CHIEF SEATS OF SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 75 APPENDIX III: COATS OF ARMS OF VARIOUS BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 78 APPENDIX IV: FOUR ANCIENT PEDIGREES OF THE BARONS OF LOUGHMOE – page 82 Revision of 18 May 2020 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND1 Brien Purcell Horan2 Copyright 2020 For centuries, the Purcells in Ireland were principally a military family, although they also played a role in the governmental and ecclesiastical life of that country. Theirs were, with some exceptions, supporting rather than leading roles. In the feudal period, they were knights, not earls. Afterwards, with occasional exceptions such as Major General Patrick Purcell, who died fighting Cromwell,3 they tended to be colonels and captains rather than generals. They served as sheriffs and seneschals rather than Irish viceroys or lords deputy. -

2016 Calendar

Acknowledgements The Heritage Office of Kilkenny County Council would like to extend their thanks to all of those who contributed to this calendar including Carrig Building Fabric Consultants, Pat Moore Photography and also the Local Studies Section of Kilkenny County Library Service for their research assistance. The following listing acknowledges, where known, those who have commissioned or designed the plaques and monuments: Old Bennettsbridge Village Creamery, commissioned by Patsy O’Brien. 1798 Memorial, commissioned by The Rower 1798 Committee; artist O’Donald family. Peg Washington’s Lane, part of the Graiguenamanagh Heritage Trail, commissioned by the Graiguenamanagh Historical Society. St. Moling’s Statue, commissioned by the people of Mullinakill; artist Patrick Malone, Cumann Luthchleas Gael, Derrylackey. Callan Tom Lyng Memorial, commissioned by the family of Tom Lyng; artist Aileen Anne Brannigan, plinth by Paddy Dowling and Rory Delaney. James Hoban Memorial, commissioned by the Spirit of Place/Spirit of Design Program; artist Architecture Students of The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC. This project is an action of the Kilkenny Heritage Plan. It was produced by the Heritage Office of Kilkenny County Council, and part funded by the Heritage Council under the County Heritage Grant Scheme. Kilkenny Signs and Stories Calendar 2016 A selection of memorials, plaques and signs in County Kilkenny Memorials and plaques are an often overlooked part Kilkenny County Council, Johns Green House, Johns of our cultural heritage. They identify and honour Green, Kilkenny. Email: dearbhala.ledwidge@ people, historic events and heritage landmarks of kilkennycoco.ie Tel: 056-7794925. the county. The Heritage Office of Kilkenny County Council has begun a project to record, photograph We would like to extend our thanks to all those who and map all of these plaques and memorials. -

Fiddown Local Area Plan 2003

Fiddown Local Area Plan 2003 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 LEGAL BASIS 1 1.2 PLANNING CONTEXT 1 1.3 LOCATIONAL CONTEXT 2 1.4 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 2 1.5 URBAN STRUCTURE 2 1.6 POPULATION 3 1.7 PLANNING HISTORY 4 1.8 DESIGNATIONS 4 1.8.1 RECORD OF PROTECTED STRUCTURES 4 1.8.2 ARCHAEOLOGY 4 1.9 NATIONAL SPATIAL STRATEGY 5 1.10 PUBLIC CONSULTATION 5 2 POLICIES AND OBJECTIVES 7 2.1 HOUSING AND POPULATION 7 2.1.1 DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 7 2.1.1.1 Development Strategy A – Expansion of Fiddown 7 2.1.1.2 Development Strategy B – Controlled growth of Fiddown 8 2.1.2 CHARACTER OF FIDDOWN 9 2.1.3 INTEGRATION OF RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENTS 11 2.2 INFRASTRUCTURE 11 2.2.1 SEWERAGE NETWORK 11 2.2.2 SURFACE WATER DRAINAGE 12 2.2.3 WATER SUPPLY 12 2.2.4 WASTE 13 2.2.5 TELECOMMUNICATIONS 14 2.3 EMPLOYMENT AND ECONOMY 14 2.3.1 RETAIL 15 2.3.2 TOURISM 16 2.4 EDUCATION AND TRAINING 17 2.4.1 ADULT EDUCATION 18 2.5 TRANSPORT 18 2.5.1 ROADS 18 2.5.2 FOOTPATHS AND LIGHTING 19 2.5.3 TRAFFIC CALMING 20 2.5.4 LINKAGES WITHIN THE VILLAGE 20 2.5.5 PUBLIC TRANSPORT 21 2.5.6 RAIL 22 2.5.7 PARKING 22 2.6 COMMUNITY FACILITIES – RECREATION 22 2.6.1 OPEN SPACE 22 2.6.2 THE RIVER SUIR 24 i Fiddown Local Area Plan 2003 2.6.3 RECREATION 25 2.7 AMENITY ENHANCEMENT 25 2.7.1 CONSERVATION 25 2.7.2 GENERAL APPEARANCE 26 2.7.3 ECOLOGY 27 2.8 COMMUNITY SUPPORTS – SOCIAL SERVICES 27 2.8.1 SERVICES 27 2.8.2 TARGET GROUPS 27 2.8.3 HEALTHCARE 28 2.8.4 CHILDCARE 28 3 DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES 30 3.1 INTRODUCTION 30 3.2 THE DEVELOPMENT BOUNDARY 30 3.3 LAND USE ZONING 30 3.3.1 RESIDENTIAL 31 3.3.2 VILLAGE -

Durrow Convent Public Water Supply

County Kilkenny Groundwater Protection Scheme Volume II: Source Protection Zones and Groundwater Quality July 2002 Dunmore Cave, County Kilkenny (photograph Terence P. Dunne) Tom Gunning, B.E., C.Eng., F.I.E.I. Ruth Buckley and Vincent Fitzsimons Director of Services Groundwater Section Kilkenny County Council Geological Survey of Ireland County Hall Beggars Bush Kilkenny Haddington Road Dublin 4 County Kilkenny Groundwater Protection Scheme Authors Ruth Buckley, Groundwater Section, Geological Survey of Ireland Vincent Fitzsimons, Groundwater Section, Geological Survey of Ireland with contributions by: Susan Hegarty, Quaternary Section Geological Survey of Ireland Cecilia Gately, Groundwater Section Geological Survey of Ireland Subsoils mapped by: Susan Hegarty, Quaternary Section, Geological Survey of Ireland Supervision: Willie Warren, Quaternary Section, Geological Survey of Ireland in collaboration with: Kilkenny County Council County Kilkenny Groundwater Protection Scheme – Volume II Table of Contents Sections 1 to 6 are contained within Volume I. They comprise an overall introduction, classifications of aquifers and vulnerability, and overall conclusions. 7. GROUNDWATER QUALITY ................................................................................................................... 4 7.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 4 7.2 SCOPE ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Recent Aquisitions to the Waterford Room Collection at the City Library

IXXX 0227 DECIES Page No. 3 Editorial. 5 Settlement and Colonisation in the brginal Areas of the Catherine Ketch Comeragh htairu. 15 Early Qlstoms Officers. Francis bbrphy 17 A Century of C3ange 1764 - 1871 J.S. Carroll 2 6 St. Brigit and the Breac - Folk. Wert Butler. 31 Heroic Rescue near Stradbally, 1875. 35 19th Ceotury Society in County Waterford Jack Wlrtchaell 4 3 Recent Additions to the 'Waterford R&' Collection in the City Library. 45 Old Waterford Society bkdership. 52 Spring and hrProgramne. Front Cover: Tintern Abbey, Co. Wexford, by Fergus Mllon. This early 13th century Cistercian abbey was founded by 'k'illiam the Marshall. At the time of the dissolutiar it was convert4 into a residence by the Colclaugh family and remained as swh until recent times. It habeen the subject of archaeological investigation and conservation by the Office of Public Works under the direction of Dr. heLynch who is be to &liver r lecture m the sibject'in'Apri1. The Old Waterford Society is very grateful to Waterford Crystal , Ltd. for their generous financial help twards the production of this issue of Decies. kies is published thrice yearly by the Old Waterford Society and is issued free to 5miiZs. All articles and illustrations are the copyright of cantributors. The Society wishes to express its appreciation of the facilities afforded to it by the Regional Technical College in the prodxtion of this issue. Editorial ng eviden ce before a Royal Commis sion early in the last century the Town Clerk of Waterford confirmed that in 1813, when the City Council were leaving their former meeting place at the Exchange on the Quay, - the Mayor gave a direction that five cartloads of old manuscripts accumulated there should be destroyed as being "useless lumber". -

IONSTRAIMÍ REACHTÚLA IR Uimh. 524 De 2003

IONSTRAIMÍ REACHTÚLA I.R. Uimh. 524 de 2003 _________ An tOrdú Logainmneacha (Contae Phort Láirge) 2003 (Prn. 1142) 2 IR 524 de 2003 An tOrdú Logainmneacha (Contae Phort Láirge) 2003 Ordaímse, ÉAMON Ó CUÍV, TD, Aire Gnóthaí Pobail, Tuaithe agus Gaeltachta, i bhfeidhmiú na gcumhachtaí a tugtar dom le halt 32(1) de Achta na dTeangacha Oifigiúla 2003 (Uimh. 32 de 2003), agus tar éis dom comhairle a fháil ón gCoimisiún Logainmneacha agus an chomhairle sin a bhreithniú, mar seo a leanas: 1. (a) Féadfar An tOrdú Logainmneacha (Contae Phort Láirge) 2003 a ghairm den Ordú seo. (b) Tagann an tOrdú seo i ngníomh ar 30 Deireadh Fómhair 2003. 2. Dearbhaítear gurb é logainm a shonraítear ag aon uimhir tagartha i gcolún (2) den Sceideal a ghabhann leis an Ordú seo an leagan Gaeilge den logainm a shonraítear i mBéarla i gcolún (1) den Sceideal a ghabhann leis an Ordú seo os comhair an uimhir tagartha sin. 3. Tá an téacs i mBéarla den Ordú seo (seachas an Sceideal leis) leagtha amach sa Tábla a ghabhann leis an Ordú seo. 3 TABLE I, ÉAMON Ó CUÍV, TD, Minister for Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs, in exercise of the powers conferred on me by section 32 of the Official Languages Act 2003 (No. 32 of 2003), and having received and considered advice from An Coimisiún Logainmneacha, make the following order: 1. (a) This Order may be cited as the Placenames (Co. Waterford) Order 2003. (b) This Order comes into operation on 30 October 2003. 2. A placename specified in column (2) of the Schedule to this Order at any reference number is declared to be the Irish language version of the placename specified in column (1) of the Schedule to this Order opposite that reference number in the English language. -

Waterford Industrial Archaeology Report

Pre-1923 Survey of the Industrial Archaeological Heritage of the County of Waterford Dublin Civic Trust April 2008 SURVEY OF PRE-1923 COUNTY WATERFORD INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE April 2008 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Executive Summary 1 3. Methodology 3 4. Industrial Archaeology in Ireland 6 - Industrial Archaeology in Context 6 - Significance of Co. Waterford Survey 7 - Legal Status of Sites 9 5. Industrial Archaeology in Waterford 12 6. Description of Typologies & Significance 15 7. Issues in Promoting Regeneration 20 8. Conclusions & Future Research 27 Bibliography 30 Inventory List 33 Inventory of Industrial Archaeological Sites 36 Knockmahon Mines, Copper Coast, Co. Waterford SURVEY OF PRE-1923 COUNTY WATERFORD INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE 1. INTRODUCTION Waterford County Council, supported by the Heritage Council, commissioned Dublin Civic Trust in July 2007 to compile an inventory of the extant pre-1923 industrial heritage structures within Waterford County. This inventory excludes Waterford City from the perimeters of study, as it is not within the jurisdiction of Waterford County Council. This survey comes from a specific objective in the Waterford County Heritage Plan 2006 – 2011, Section 1.1.17 which requests “…a database (sic) the industrial and engineering heritage of County Waterford”. The aim of the report, as discussed with Waterford County Council, is not only to record an inventory of industrial archaeological heritage but to contextualise its significance. It was also anticipated that recommendations be made as to the future re-use of such heritage assets and any unexplored areas be highlighted. Mary Teehan buildings archaeologist, and Ronan Olwill conservation planner, for Dublin Civic Trust, Nicki Matthews conservation architect and Daniel Noonan consultant archaeologist were the project team. -

The War of Independence in County Kilkenny: Conflict, Politics and People

The War of Independence in County Kilkenny: Conflict, Politics and People Eoin Swithin Walsh B.A. University College Dublin College of Arts and Celtic Studies This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the Master of Arts in History July 2015 Head of School: Dr Tadhg Ó hAnnracháin Supervisor of Research: Professor Diarmaid Ferriter P a g e | 2 Abstract The array of publications relating to the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) has, generally speaking, neglected the contributions of less active counties. As a consequence, the histories of these counties regarding this important period have sometimes been forgotten. With the recent introduction of new source material, it is now an opportune time to explore the contributions of the less active counties, to present a more layered view of this important period of Irish history. County Kilkenny is one such example of these overlooked counties, a circumstance this dissertation seeks to rectify. To gain a sense of the contemporary perspective, the first two decades of the twentieth century in Kilkenny will be investigated. Significant events that occurred in the county during the period, including the Royal Visit of 1904 and the 1917 Kilkenny City By-Election, will be examined. Kilkenny’s IRA Military campaign during the War of Independence will be inspected in detail, highlighting the major confrontations with Crown Forces, while also appraising the corresponding successes and failures throughout the county. The Kilkenny Republican efforts to instigate a ‘counter-state’ to subvert British Government authority will be analysed. In the political sphere, this will focus on the role of Local Government, while the administration of the Republican Courts and the Republican Police Force will also be examined. -

Recently Deceased Sr. Máire Convery, R.S.H.M., Madonna House

Mass schedule Masses will be celebrated and livestreamed on our webcams, facebook live, & broadcast via Parish Radio 103.9fm Weekends Saturday Evening 6pm Vigil Mass from Slieverue Sunday 11.30am Sunday Mass from Ferrybank Daily Mass Recently Deceased Monday - Thursday - 10am Mass from Ferrybank Sr. Máire Convery, Friday - 10 am Mass from Slieverue R.S.H.M., Madonna House, Ferrybank/Kilkenny/Mayo Ferrybank/Slieverue Parish Christmas Cards Christmas Cards with images of Ferrybank & Slieverue Church are available to order from the Parish Elzbieta Szemiako, Office and cost €2 which include the card and share in our Novena of Masses which will be offered Leaca Ard, Abbey Rd., over the Christmas period for our deceased loved ones. Images of the Christmas Cards are available Ferrybank to view on the parish website. Robert Michael Nolan, November the month we pray for and remember our loved ones in a special New Ross, Co. Wexford. way … Mass is offered for all on the November list of Remembrance. Names can still be submitted of Month’s Mind those you would like remembered. Envelopes are available at the back of the Church. Below you George Heaslip will find an outline of how we will remember all who have died during the coming month. Michael Cummins Book of Remembrance Anniversaries In past years you will have been invited to write the names of your deceased family members and Jim & Lena Lawless friends in a special Book placed in the Church. This year this will not be possible but there are Margaret Brown alternatives. a. phone the Parish Office 051 830813 with your list of names and we will include them in Bridget & John Croke the Book of Remembrance for you b. -

Doing Local History in County Kilkenny: an Index

900 LOCAL HISTORY IN COLTN':'¥ PJ.K.T?tTNY W'·;. Doing Local History in County Kilkenny: Keeffe, .James lnistioge 882 Keeffe, Mary Go!umbkill & CourtT'ab(\.~(;J 3'75 An Index to the Probate Court Papers, Keefe, Michael 0 ........ Church Clara ,)"~,) Keeffe, Patrick CoJumkille 8'3(' 1858·1883 Keeffe, Patrick Blickana R?5 Keeffe, Philip, Ca.stJt! Eve B?~~ Marilyn Silverman. Ph,D, Keely (alias Kealy), Richard (see Kealy above) PART 2 : 1- Z Kiely .. James Foyle Taylor (Foylatalure) 187S Kelly, Catherine Graiguenamanagh 1880 Note: Part 1 (A . H) of this index was published in Kelly, Daniel Tullaroan 187a Kilkenny Review 1989 (No. 41. Vol. 4. No.1) Pages 621>-64,9. Kelly, David Spring Hill 1878 For information on the use of wills in historical rel,e2lrch, Kelly, James Goresbridge 1863 Kelly, Jeremiah Tuliyroane (T"llaroar.) 1863 the nature of Probate Court data and an explanation Kelly, John Dungarvan 1878 index for Co. Kilkenny see introduction to Part 1. Kelly, John Clomanto (Clomantagh) lS82 Kelly, John Graiguenamanagh !883 Kelly, John TulIa't"oan J88; Kelly, Rev. John Name Address Castlecomer ~883 Kelly, Martin Curraghscarteen :;;61 Innes. Anne Kilkenny Kelly, Mary lO.:· Cur,:aghscarteei'. _~; .... I Tl'win, Rev. Crinus Kilfane Gl.ebe Kelly, Michael 3an:,"~uddihy lSS~) Irwin, Mary Grantsborough ' Kelly, Patrick Curraghscarteen 1862 Izod, Henry Chapelizod House" . (\,~. Kelly, Patrick Sp";.llgfield' , 0~,,j !zod, Mary Kells HOllse, Thomastown Kelly. Philip Tul!arcar.. ':'!}S5 Izod, Thomas Kells Kelly, Richard Featha:ilagh :.07'i Kelly, Thomas Kilkenny 1.:)68 Jacob, James Castlecomer Kelly, Thomas Ir.shtown" :874 ,Jacob, Thomas J. -

Irish Life and Lore Series the KILKENNY COLLECTION SECOND

Irish Life and Lore Series THE KILKENNY COLLECTION SECOND SERIES _____________ CATALOGUE OF 52 RECORDINGS www.irishlifeandlore.com Recordings compiled by : Maurice O’Keeffe Catalogue Editor : Jane O’Keeffe and Alasdair McKenzie Secretarial work by : n.b.services, Tralee Recordings mastered by : Midland Duplication, Birr, Co. Offaly Privately published by : Maurice and Jane O’Keeffe, Tralee All rights reserved © 2008 ISBN : 978-0-9555326-8-9 Supported By Kilkenny County Library Heritage Office Irish Life and Lore Series Maurice and Jane O’Keeffe, Ballyroe, Tralee, County Kerry e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.irishlifeandlore.com Telephone: + 353 (66) 7121991/ + 353 87 2998167 All rights reserved – © 2008 Irish Life and Lore Kilkenny Collection Second Series NAME: JANE O’NEILL, CHATSWORTH, CLOGH, CASTLECOMER Title: Irish Life and Lore Kilkenny Collection, CD 1 Subject: Reminiscences of a miner’s daughter Recorded by: Maurice O’Keeffe Date: April 2008 Time: 44:13 Description: Jane O’Neill grew up in a council cottage, one of 14 children. Due to the size of the family, she was brought up by her grandmother. Her father worked in the coal mines, and he was the first man to reach the coal face when the Deerpark coal mine was opened in the 1920s. He died at a young age of silicosis, as did many of the other miners. Jane’s other recollections relate to her time working for the farmers in Inistioge. NAME: VIOLET MADDEN, AGE 77, CASTLECOMER Title: Irish Life and Lore Kilkenny Collection, CD 2 Subject: Memories of Castlecomer in times past Recorded by: Maurice O’Keeffe Date: April 2008 Time: 50:34 Description: This recording begins with the tracing of the ancestry of Violet Madden’s family, the Ryans.