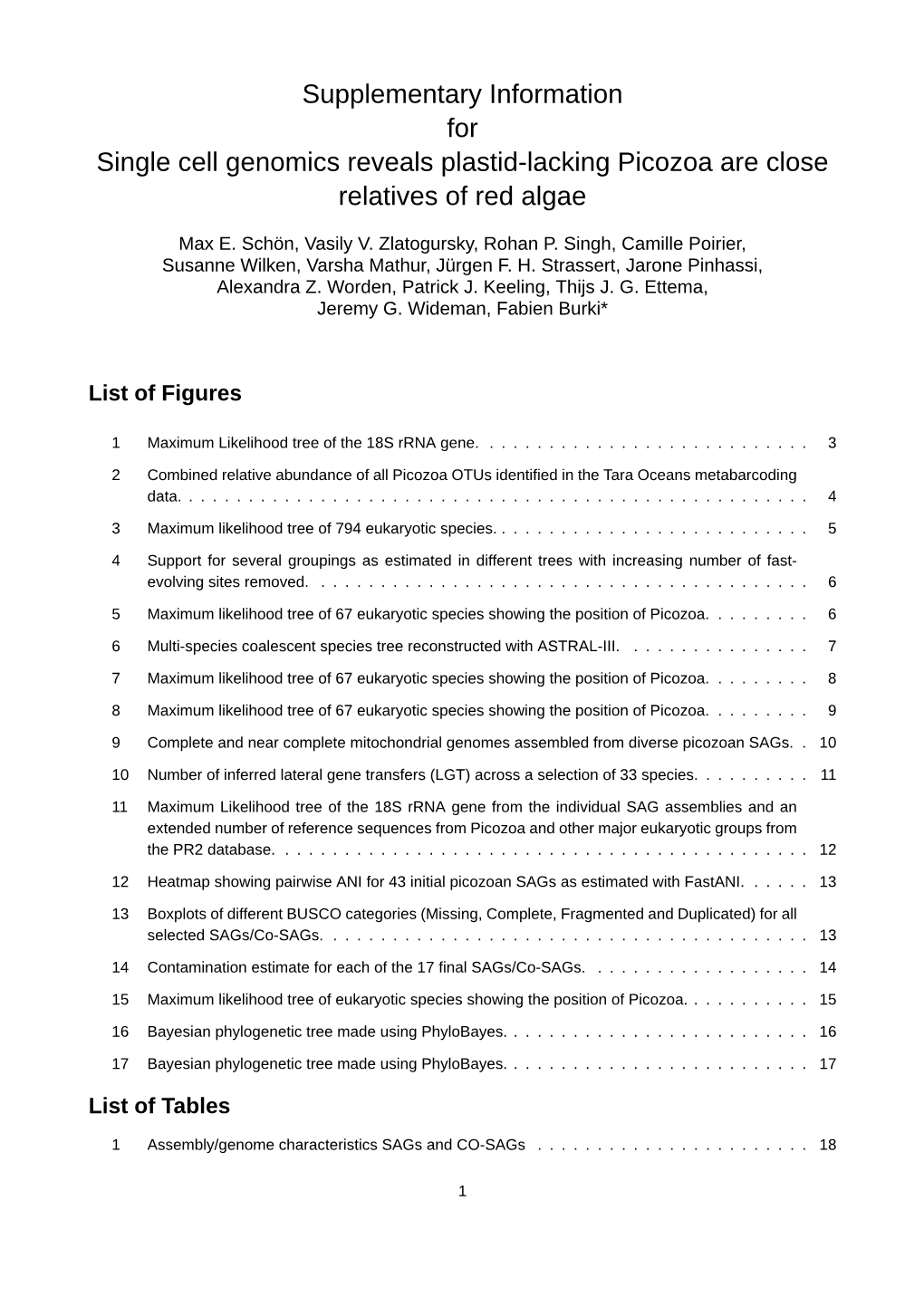

Single Cell Genomics Reveals Plastid-Lacking Picozoa Are Close Relatives of Red Algae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology of Oceanic Coccolithophores. I. Nutritional Preferences of the Two Stages in the Life Cycle of Coccolithus Braarudii and Calcidiscus Leptoporus

AQUATIC MICROBIAL ECOLOGY Vol. 44: 291–301, 2006 Published October 10 Aquat Microb Ecol Ecology of oceanic coccolithophores. I. Nutritional preferences of the two stages in the life cycle of Coccolithus braarudii and Calcidiscus leptoporus Aude Houdan, Ian Probert, Céline Zatylny, Benoît Véron*, Chantal Billard Laboratoire de Biologie et Biotechnologies Marines, Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, Esplanade de la Paix, 14032 Caen Cedex, France ABSTRACT: Coccolithus braarudii and Calcidiscus leptoporus are 2 coccolithophores (Prymnesio- phyceae: Haptophyta) known to possess a complex heteromorphic life cycle, with alternation between a motile holococcolith-bearing haploid stage and a non-motile heterococcolith-bearing diploid stage. The ecological implications of this type of life cycle in coccolithophores are currently poorly known. The nutritional preferences of each stage of both species, and their growth response to conditions of turbulence were investigated by varying their growth conditions. Of the different cul- ture media tested, only the synthetic seawater medium did not support the growth of both stages of C. braarudii and C. leptoporus. With natural seawater-based media, the growth rate of the haploid phase of both coccolithophores was stimulated by the addition of soil extract (K/2: 0.23 ± 0.02 d–1 and K/2 with soil extract 0.35 ± 0.01 d–1 for the C. braarudii haploid stage), while the diploid phase was not, indicating that the motile stage is capable of utilizing compounds present in soil extract or ingest- ing bacteria that are activated in enriched media. The addition of sodium acetate to the medium also stimulated the haploid phase of C. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE MACRONUTRIENTS SHAPE MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES, GENE EXPRESSION AND PROTEIN EVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By JOSHUA THOMAS COOPER Norman, Oklahoma 2017 MACRONUTRIENTS SHAPE MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES, GENE EXPRESSION AND PROTEIN EVOLUTION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY AND PLANT BIOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Boris Wawrik, Chair ______________________________ Dr. J. Phil Gibson ______________________________ Dr. Anne K. Dunn ______________________________ Dr. John Paul Masly ______________________________ Dr. K. David Hambright ii © Copyright by JOSHUA THOMAS COOPER 2017 All Rights Reserved. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my two advisors Dr. Boris Wawrik and Dr. J. Phil Gibson for helping me become a better scientist and better educator. I would also like to thank my committee members Dr. Anne K. Dunn, Dr. K. David Hambright, and Dr. J.P. Masly for providing valuable inputs that lead me to carefully consider my research questions. I would also like to thank Dr. J.P. Masly for the opportunity to coauthor a book chapter on the speciation of diatoms. It is still such a privilege that you believed in me and my crazy diatom ideas to form a concise chapter in addition to learn your style of writing has been a benefit to my professional development. I’m also thankful for my first undergraduate research mentor, Dr. Miriam Steinitz-Kannan, now retired from Northern Kentucky University, who was the first to show the amazing wonders of pond scum. Who knew that studying diatoms and algae as an undergraduate would lead me all the way to a Ph.D. -

An Explanation for the 18O Excess in Noelaerhabdaceae Coccolith Calcite

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 189 (2016) 132–142 www.elsevier.com/locate/gca An explanation for the 18O excess in Noelaerhabdaceae coccolith calcite M. Hermoso a,⇑, F. Minoletti b,c, G. Aloisi d,e, M. Bonifacie f, H.L.O. McClelland a,1, N. Labourdette b,c, P. Renforth g, C. Chaduteau f, R.E.M. Rickaby a a University of Oxford – Department of Earth Sciences, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3AN, United Kingdom b Sorbonne Universite´s, UPMC Universite´ Paris 06 – Institut de Sciences de la Terre de Paris (ISTeP), 4 Place Jussieu, 75252 Paris Cedex 05, France c CNRS – UMR 7193 ISTeP, 4 Place Jussieu, 75252 Paris Cedex 05, France d Sorbonne Universite´s, UPMC Universite´ Paris 06 – UMR 7159 LOCEAN, 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France e CNRS – UMR 7159 LOCEAN, 4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France f Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Sorbonne Paris Cite´, Universite´ Paris-Diderot, UMR CNRS 7154, 1 rue Jussieu, 75238 Paris Cedex, France g Cardiff University – School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Parks Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, United Kingdom Received 10 November 2015; accepted in revised form 11 June 2016; available online 18 June 2016 Abstract Coccoliths have dominated the sedimentary archive in the pelagic environment since the Jurassic. The biominerals pro- duced by the coccolithophores are ideally placed to infer sea surface temperatures from their oxygen isotopic composition, as calcification in this photosynthetic algal group only occurs in the sunlit surface waters. In the present study, we dissect the isotopic mechanisms contributing to the ‘‘vital effect”, which overprints the oceanic temperatures recorded in coccolith calcite. -

The Life Cycle and Genetic Structure of the Red Alga Furcellaria Lumbricalis on a Salinity Gradient

WALTER AND ANDRÉE DE NOTTBECK FOUNDATION SCIENTIFIC REPORTS View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE No. 33 provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto The life cycle and genetic structure of the red alga Furcellaria lumbricalis on a salinity gradient KIRSI KOSTAMO Academic dissertation in Ecology, to be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Biosciences of the University of Helsinki, for public criticism in the Auditorium 1041, Biocenter 2, University of Helsinki, Viikinkaari 5, Helsinki, on January 25th, 2008, at 12 noon. HELSINKI 2008 This thesis is based on the following papers, which will be referred to in the text by their Roman numerals: I. Kostamo, K. & Mäkinen, A. 2006: Observations on the mode and seasonality of reproduction in Furcellaria lumbricalis (Gigartinales, Rhodophyta) populations in the northern Baltic Sea. – Bot. Mar. 49: 304-309. II Korpelainen, H., Kostamo, K. & Virtanen, V. 2007: Microsatellite marker identifi cation using genome screening and restriction-ligation. – BioTechniques 42: 479-486. III Kostamo, K., Korpelainen, H., Maggs, C. A. & Provan, J. 2007: Genetic variation among populations of the red alga Furcellaria lumbricalis in northern Europe. – Manuscript. IV Kostamo, K. & Korpelainen, H. 2007: Clonality and small-scale genetic diversity within populations of the red alga Furcellaria lumbricalis (Rhodophyta) in Ireland and in the northern Baltic Sea. – Manuscript. Paper I is printed with permission from Walter de Gruyter Publishers and paper II with permission from BioTechniques. Reviewers: Dr. Elina Leskinen Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences University of Helsinki Finland Prof. Kerstin Johannesson Tjärnö Marine Biological Laboratory University of Gothenburg Sweden Opponent: Dr. -

Divergence Time Estimates and the Evolution of Major Lineages in The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Divergence time estimates and the evolution of major lineages in the florideophyte red algae Received: 31 March 2015 Eun Chan Yang1,2, Sung Min Boo3, Debashish Bhattacharya4, Gary W. Saunders5, Accepted: 19 January 2016 Andrew H. Knoll6, Suzanne Fredericq7, Louis Graf8 & Hwan Su Yoon8 Published: 19 February 2016 The Florideophyceae is the most abundant and taxonomically diverse class of red algae (Rhodophyta). However, many aspects of the systematics and divergence times of the group remain unresolved. Using a seven-gene concatenated dataset (nuclear EF2, LSU and SSU rRNAs, mitochondrial cox1, and plastid rbcL, psaA and psbA genes), we generated a robust phylogeny of red algae to provide an evolutionary timeline for florideophyte diversification. Our relaxed molecular clock analysis suggests that the Florideophyceae diverged approximately 943 (817–1,049) million years ago (Ma). The major divergences in this class involved the emergence of Hildenbrandiophycidae [ca. 781 (681–879) Ma], Nemaliophycidae [ca. 661 (597–736) Ma], Corallinophycidae [ca. 579 (543–617) Ma], and the split of Ahnfeltiophycidae and Rhodymeniophycidae [ca. 508 (442–580) Ma]. Within these clades, extant diversity reflects largely Phanerozoic diversification. Divergences within Florideophyceae were accompanied by evolutionary changes in the carposporophyte stage, leading to a successful strategy for maximizing spore production from each fertilization event. Our research provides robust estimates for the divergence times of major lineages within the Florideophyceae. This timeline was used to interpret the emergence of key morphological innovations that characterize these multicellular red algae. The Florideophyceae is the most taxon-rich red algal class, comprising 95% (6,752) of currently described species of Rhodophyta1 and possibly containing many more cryptic taxa2. -

The Plankton Lifeform Extraction Tool: a Digital Tool to Increase The

Discussions https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2021-171 Earth System Preprint. Discussion started: 21 July 2021 Science c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Open Access Open Data The Plankton Lifeform Extraction Tool: A digital tool to increase the discoverability and usability of plankton time-series data Clare Ostle1*, Kevin Paxman1, Carolyn A. Graves2, Mathew Arnold1, Felipe Artigas3, Angus Atkinson4, Anaïs Aubert5, Malcolm Baptie6, Beth Bear7, Jacob Bedford8, Michael Best9, Eileen 5 Bresnan10, Rachel Brittain1, Derek Broughton1, Alexandre Budria5,11, Kathryn Cook12, Michelle Devlin7, George Graham1, Nick Halliday1, Pierre Hélaouët1, Marie Johansen13, David G. Johns1, Dan Lear1, Margarita Machairopoulou10, April McKinney14, Adam Mellor14, Alex Milligan7, Sophie Pitois7, Isabelle Rombouts5, Cordula Scherer15, Paul Tett16, Claire Widdicombe4, and Abigail McQuatters-Gollop8 1 10 The Marine Biological Association (MBA), The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth, PL1 2PB, UK. 2 Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquacu∑lture Science (Cefas), Weymouth, UK. 3 Université du Littoral Côte d’Opale, Université de Lille, CNRS UMR 8187 LOG, Laboratoire d’Océanologie et de Géosciences, Wimereux, France. 4 Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Prospect Place, Plymouth, PL1 3DH, UK. 5 15 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), CRESCO, 38 UMS Patrinat, Dinard, France. 6 Scottish Environment Protection Agency, Angus Smith Building, Maxim 6, Parklands Avenue, Eurocentral, Holytown, North Lanarkshire ML1 4WQ, UK. 7 Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), Lowestoft, UK. 8 Marine Conservation Research Group, University of Plymouth, Drake Circus, Plymouth, PL4 8AA, UK. 9 20 The Environment Agency, Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Peterborough, PE4 6HL, UK. 10 Marine Scotland Science, Marine Laboratory, 375 Victoria Road, Aberdeen, AB11 9DB, UK. -

Multigene Eukaryote Phylogeny Reveals the Likely Protozoan Ancestors of Opis- Thokonts (Animals, Fungi, Choanozoans) and Amoebozoa

Accepted Manuscript Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opis- thokonts (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa Thomas Cavalier-Smith, Ema E. Chao, Elizabeth A. Snell, Cédric Berney, Anna Maria Fiore-Donno, Rhodri Lewis PII: S1055-7903(14)00279-6 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.012 Reference: YMPEV 4996 To appear in: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Received Date: 24 January 2014 Revised Date: 2 August 2014 Accepted Date: 11 August 2014 Please cite this article as: Cavalier-Smith, T., Chao, E.E., Snell, E.A., Berney, C., Fiore-Donno, A.M., Lewis, R., Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opisthokonts (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (2014), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.ympev.2014.08.012 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. 1 1 Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opisthokonts 2 (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa 3 4 Thomas Cavalier-Smith1, Ema E. Chao1, Elizabeth A. Snell1, Cédric Berney1,2, Anna Maria 5 Fiore-Donno1,3, and Rhodri Lewis1 6 7 1Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK. -

Chemical Composition and Potential Practical Application of 15 Red Algal Species from the White Sea Coast (The Arctic Ocean)

molecules Article Chemical Composition and Potential Practical Application of 15 Red Algal Species from the White Sea Coast (the Arctic Ocean) Nikolay Yanshin 1, Aleksandra Kushnareva 2, Valeriia Lemesheva 1, Claudia Birkemeyer 3 and Elena Tarakhovskaya 1,4,* 1 Department of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Biology, St. Petersburg State University, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] (N.Y.); [email protected] (V.L.) 2 N. I. Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry, 190000 St. Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Chemistry and Mineralogy, University of Leipzig, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; [email protected] 4 Vavilov Institute of General Genetics RAS, St. Petersburg Branch, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Though numerous valuable compounds from red algae already experience high demand in medicine, nutrition, and different branches of industry, these organisms are still recognized as an underexploited resource. This study provides a comprehensive characterization of the chemical composition of 15 Arctic red algal species from the perspective of their practical relevance in medicine and the food industry. We show that several virtually unstudied species may be regarded as promis- ing sources of different valuable metabolites and minerals. Thus, several filamentous ceramialean algae (Ceramium virgatum, Polysiphonia stricta, Savoiea arctica) had total protein content of 20–32% of dry weight, which is comparable to or higher than that of already commercially exploited species Citation: Yanshin, N.; Kushnareva, (Palmaria palmata, Porphyra sp.). Moreover, ceramialean algae contained high amounts of pigments, A.; Lemesheva, V.; Birkemeyer, C.; macronutrients, and ascorbic acid. Euthora cristata (Gigartinales) accumulated free essential amino Tarakhovskaya, E. -

Coccolithophore Distribution in the Mediterranean Sea and Relate A

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Ocean Sci. Discuss., 11, 613–653, 2014 Open Access www.ocean-sci-discuss.net/11/613/2014/ Ocean Science OSD doi:10.5194/osd-11-613-2014 Discussions © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 11, 613–653, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Ocean Science (OS). Coccolithophore Please refer to the corresponding final paper in OS if available. distribution in the Mediterranean Sea Is coccolithophore distribution in the A. M. Oviedo et al. Mediterranean Sea related to seawater carbonate chemistry? Title Page Abstract Introduction A. M. Oviedo1, P. Ziveri1,2, M. Álvarez3, and T. Tanhua4 Conclusions References 1Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA), Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona (UAB), 08193 Bellaterra, Spain Tables Figures 2Earth & Climate Cluster, Department of Earth Sciences, FALW, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, FALW, HV1081 Amsterdam, the Netherlands J I 3IEO – Instituto Espanol de Oceanografia, Apd. 130, A Coruna, 15001, Spain 4GEOMAR Helmholtz-Zentrum für Ozeanforschung Kiel, Marine Biogeochemistry, J I Duesternbrooker Weg 20, 24105 Kiel, Germany Back Close Received: 31 December 2013 – Accepted: 15 January 2014 – Published: 20 February 2014 Full Screen / Esc Correspondence to: A. M. Oviedo ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 613 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract OSD The Mediterranean Sea is considered a “hot-spot” for climate change, being char- acterized by oligotrophic to ultra-oligotrophic waters and rapidly changing carbonate 11, 613–653, 2014 chemistry. Coccolithophores are considered a dominant phytoplankton group in these 5 waters. -

Download PDF Version

MarLIN Marine Information Network Information on the species and habitats around the coasts and sea of the British Isles A red seaweed (Furcellaria lumbricalis) MarLIN – Marine Life Information Network Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Review Will Rayment 2008-05-22 A report from: The Marine Life Information Network, Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Please note. This MarESA report is a dated version of the online review. Please refer to the website for the most up-to-date version [https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1616]. All terms and the MarESA methodology are outlined on the website (https://www.marlin.ac.uk) This review can be cited as: Rayment, W.J. 2008. Furcellaria lumbricalis A red seaweed. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.17031/marlinsp.1616.2 The information (TEXT ONLY) provided by the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Note that images and other media featured on this page are each governed by their own terms and conditions and they may or may not be available for reuse. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are available here. Based on a work at www.marlin.ac.uk (page left blank) Date: 2008-05-22 A red seaweed (Furcellaria lumbricalis) - Marine Life Information Network See online review for distribution map The seaweed Furcellaria lumbricalis, plant with fertile branches. -

Fig.S1. the Pairwise Aligments of High Scoring Pairs of Recognizable Pseudogenes

LysR transcriptional regulator Identities = 57/164 (35%), Positives = 82/164 (50%), Gaps = 13/164 (8%) 70530- SNQAIKTYLMPK*LRLLRQK*SPVEFQLQVHLIKKIRLNIVIRDINLTIIEN-TPVKLKI -70354 ++Q TYLMP+ + L RQK V QLQVH ++I ++ INL II P++LK 86251- ASQTTGTYLMPRLIGLFRQKYPQVAVQLQVHSTRRIAWSVANGHINLAIIGGEVPIELKN -86072 70353- FYTLLRMKERI*H*YCLGFL------FQFLIAYKKKNLYGLRLIKVDIPFPIRGIMNNP* -70192 + E L + F L + +K++LY LR I +D IR +++ 86071- MLQVTSYAED-----ELALILPKSHPFSMLRSIQKEDLYRLRFIALDRQSTIRKVIDKVL -85907 70191- IKTELIPRNLN-EMELSLFKPIKNAV*PGLNVTLIFVSAIAKEL -70063 + + EMEL+ + IKNAV GL + VSAIAKEL 85906- NQNGIDSTRFKIEMELNSVEAIKNAVQSGLGAAFVSVSAIAKEL -85775 ycf3 Photosystem I assembly protein Identities = 25/59 (42%), Positives = 39/59 (66%), Gaps = 3/59 (5%) 19162- NRSYML-SIQCM-PNNSDYVNTLKHCR*ALDLSSKL-LAIRNVTISYYCQDIIFSEKKD -19329 +RSY+L +I + +N +YV L++ ALDL+S+L AI N+ + Y+ Q + SEKKD 19583- DRSYILYNIGLIYASNGEYVKALEYYHQALDLNSRLPPAINNIAVIYHYQGVKASEKKD -19759 Fig.S1. The pairwise aligments of high scoring pairs of recognizable pseudogenes. The upper amino acid sequences indicates Cryptomonas sp. SAG977-2f. The lower sequences are corresponding amino acid sequences of homologs in C. curvata CCAP979/52. Table S1. Presence/absence of protein genes in the plastid genomes of Cryptomonas and representative species of Cryptomonadales. Note; y indicates pseudogenes. Photosynthetic Non-Photosynthetic Guillardia Rhodomonas Cryptomonas C. C. curvata C. curvata parameciu Guillardia Rhodomonas FBCC300 CCAP979/ SAG977 CCAC1634 m theta salina -2f B 012D 52 CCAP977/2 a rps2 + + + + -

Lateral Gene Transfer of Anion-Conducting Channelrhodopsins Between Green Algae and Giant Viruses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042127; this version posted April 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 5 Lateral gene transfer of anion-conducting channelrhodopsins between green algae and giant viruses Andrey Rozenberg 1,5, Johannes Oppermann 2,5, Jonas Wietek 2,3, Rodrigo Gaston Fernandez Lahore 2, Ruth-Anne Sandaa 4, Gunnar Bratbak 4, Peter Hegemann 2,6, and Oded 10 Béjà 1,6 1Faculty of Biology, Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel. 2Institute for Biology, Experimental Biophysics, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Invalidenstraße 42, Berlin 10115, Germany. 3Present address: Department of Neurobiology, Weizmann 15 Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel. 4Department of Biological Sciences, University of Bergen, N-5020 Bergen, Norway. 5These authors contributed equally: Andrey Rozenberg, Johannes Oppermann. 6These authors jointly supervised this work: Peter Hegemann, Oded Béjà. e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] 20 ABSTRACT Channelrhodopsins (ChRs) are algal light-gated ion channels widely used as optogenetic tools for manipulating neuronal activity 1,2. Four ChR families are currently known. Green algal 3–5 and cryptophyte 6 cation-conducting ChRs (CCRs), cryptophyte anion-conducting ChRs (ACRs) 7, and the MerMAID ChRs 8. Here we 25 report the discovery of a new family of phylogenetically distinct ChRs encoded by marine giant viruses and acquired from their unicellular green algal prasinophyte hosts.