A Comparison of Arctic Tern Ster a Paradisaea And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus argentatus - fuscus - cachinnans) as a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations Dorit Liebers-Helbig, Viviane Sternkopf, Andreas J. Helbig{, and Peter de Knijff Abstract Under what circumstances speciation in sexually reproducing animals can occur without geographical disjunction is still controversial. According to the ring species model, a reproductive barrier may arise through “isolation-by-distance” when peripheral populations of a species meet after expanding around some uninhabitable barrier. The classical example for this kind of speciation is the herring gull (Larus argentatus) complex with a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. An analysis of mitochondrial DNA variation among 21 gull taxa indicated that members of this complex differentiated largely in allopatry following multiple vicariance and long-distance colonization events, not primarily through “isolation-by-distance”. In a recent approach, we applied nuclear intron sequences and AFLP markers to be compared with the mitochondrial phylogeography. These markers served to reconstruct the overall phylogeny of the genus Larus and to test for the apparent biphyletic origin of two species (argentatus, hyperboreus) as well as the unex- pected position of L. marinus within this complex. All three taxa are members of the herring gull radiation but experienced, to a different degree, extensive mitochon- drial introgression through hybridization. The discrepancies between the mitochon- drial gene tree and the taxon phylogeny based on nuclear markers are illustrated. 1 Introduction Ernst Mayr (1942), based on earlier ideas of Stegmann (1934) and Geyr (1938), proposed that reproductive isolation may evolve in a single species through D. Liebers-Helbig (*) and V. Sternkopf Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund, Germany e-mail: [email protected] P. -

Patterns of Prey Provisioning in Relation to Chick Age in the South American Tern (Sterna Hirundinacea)

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 22: 361–368, 2011 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society PATTERNS OF PREY PROVISIONING IN RELATION TO CHICK AGE IN THE SOUTH AMERICAN TERN (STERNA HIRUNDINACEA) Alejandro A. Fernández Ajó1, Alejandro Gatto2, & Pablo Yorio2,3 1Univ. Nacional de la Patagonia “San Juan Bosco”, Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina. 2Centro Nacional Patagónico (CONICET), Boulevard Brown 2915, U9120ACV Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina. E-mail: [email protected] 3Wildlife Conservation Society, Amenabar 1595 – Piso 2 – Oficina 19, C1426AKC Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Resumen. – Patrones de abastecimiento de presas en relación con la edad de pollos en el Gavi- otín Sudamericano (Sterna hirundinacea). – El estudio de los patrones temporales en la composición de la dieta es clave para interpretar ciertos aspectos de la ecología e historia de vida de las aves mari- nas. La variación en la composición y tamaño de presas en relación con la edad de los pollos fue evalu- ado en una colonia de Gaviotín Sudamericano (Sterna hirundinacea) en Punta Loma, Argentina, durante la temporada reproductiva del 2006. La dieta de los pollos de Gaviotín Sudamericano incluyó al menos 12 especies de presa. El pescado, mayormente anchoíta (Engraulis anchoita) y pejerrey (Odontesthes argentinensis) fue la principal presa entregada (91%) a los pollos. La proporción relativa de tipos de presa varió entre las clases de edad de los pollos, y la proporción de Anchoíta en la dieta se incrementó con la edad de los mismos, alcanzando el 58% en las crías mayores. El tamaño de las presas aumentó con la edad de los pollos. Las presas robadas por otros gaviotines adultos fueron significativamente más grandes que aquellas consumidas por los pollos. -

First Confirmed Record of Belcher's Gull Larus Belcheri for Colombia with Notes on the Status of Other Gull Species

First confirmed record of Belcher's Gull Larus belcheri for Colombia with notes on the status of other gull species Primer registro confirmado de la Gaviota Peruana Larus belcheri para Colombia con notas sobre el estado de otras especies de gaviotas Trevor Ellery1 & José Ferney Salgado2 1 Independent. Email: [email protected] 2 Corporación para el Fomento del Aviturismo en Colombia. Abstract We present photographic records of a Belcher's Gull Larus belcheri from the Colombian Caribbean region. These are the first confirmed records of this species in the country. Keywords: new record, range extension, gull, identification. Resumen Presentamos registros fotograficos de un individuo de la Gaviota Peruana Larus belcheri en la region del Caribe de Colombia. Estos son los primeros registros confirmados para el país. Palabras clave: Nuevo registro, extensión de distribución, gaviota, identificación. Introduction the Pacific Ocean coasts of southern South America, and Belcher's Gull or Band-tailed Gull Larus belcheri has long Olrog's Gull L. atlanticus of southern Brazil, Uruguay and been considered a possible or probable species for Argentina (Howell & Dunn 2007, Remsen et al. 2018). Colombia, with observations nearby from Panama (Hilty & Brown 1986). It was first listed for Colombia by Salaman A good rule of thumb for gulls in Colombia is that if it's not et al. (2001) without any justification or notes, perhaps on a Laughing Gull Leucophaeus atricilla, then it's interesting. the presumption that the species could never logically have A second good rule of thumb for Colombian gulls is that if reached the Panamanian observation locality from its it's not a Laughing Gull, you are probably watching it at Los southern breeding grounds without passing through the Camarones or Santuario de Fauna y Flora Los Flamencos, country. -

Fastest Migration Highest

GO!” Everyone knows birds can fly. ET’S But not everyone knows that “L certain birds are really, really good at it. Meet a few of these champions of the skies. Flying Acby Ellen eLambeth; art sby Dave Clegg! Highest You don’t have to be a lightweight to fly high. Just look at a Ruppell’s griffon vulture (left). One was recorded flying at an altitude of 36,000 feet. That’s as high as passenger planes fly! In fact, it’s so high that you would pass out from lack of oxygen if you weren’t inside a plane. How does the vulture manage? It has Fastest (on the level) Swifts are birds that have that name for good special blood cells that make a small amount reason: They’re speedy! The swiftest bird using its own of oxygen go a long way. flapping-wing power is the common swift of Europe, Asia, and Africa (below). It’s been clocked at nearly 70 miles per hour. That’s the speed limit for cars on some highways. Vroom-vroom! Fastest (in a dive) Fastest Migration With gravity helping out, a bird can pick up extra speed. Imagine taking a trip of about 4,200 And no bird can go faster than a peregrine falcon in a dive miles. Sure, you could easily do it in an airplane. after prey (right). In fact, no other animal on Earth can go as But a great snipe (right) did it on the wing in just fast as a peregrine: more than 200 miles per hour! three and a half days! That means it averaged about 60 miles The prey, by the way, is usually another bird, per hour during its migration between northern which the peregrine strikes in mid-air with its balled-up Europe and central Africa. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Environmental Contaminants in Arctic Tern Eggs from Petit Manan Island

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine May 2001 Mission Statement U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service “Our mission is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance the nation’s fish and wildlife and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.” Suggested citation: Mierzykowski S.E., J.L. Megyesi and K.C. Carr. 2001. Environmental contaminants in Arctic tern eggs from Petit Manan Island. USFWS. Spec. Proj. Rep. FY96-MEFO-6-EC. Maine Field Office. Old Town, ME. 40 pp. Report reformatted 1/2009 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine Prepared by: Steven E. Mierzykowski1, Jennifer L. Megyesi2, and Kenneth C. Carr3 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Maine Field Office 1033 South Main Street Old Town, Maine 04468 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Main Street, P.O. Box 279 Milbridge, Maine 04658 3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service New England Field Office 70 Commercial Street, Suite 300 Concord, New Hampshire 03301-5087 May 2001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Petit Manan Island is a 3.5-hectare (~ 9 acre) island that lies approximately 4-kilometers (2.5-miles) from the coastline of Petit Manan Point, Steuben, Washington County, Maine. It is one of nearly 40 coastal islands within the Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge. -

INFORME July 2014

Chapter 3: Baseline EIA Espejo de Tarapacá Region of Tarapacá, Chile INFORME July 2014 Prepared by: Environmental management Consultants S. A Father Mariano 103 Of. 307 7500499, Providencia, Chile Phone: + 56 2 719 5600 Fax: + 56 2 235 1100 www.gac.cl Capítulo 3: Línea de Base EIA Proyecto Espejo de Tarapacá Index 3. BASELINE ......................................................................................................................................... 3-1 3.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3-1 3.2. Physical environment ................................................................................................................. 3-2 3.2.1 Atmosphere ........................................................................................................................ 3-2 3.2.1.1 Meteorology .................................................................................................................... 3-2 3.2.1.2 Air quality ........................................................................................................................ 3-5 3.2.1.3 Noise and vibration ......................................................................................................... 3-9 3.2.1.4 Electromagnetic fields .................................................................................................. 3-29 3.2.1.5 Luminosity .................................................................................................................... -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

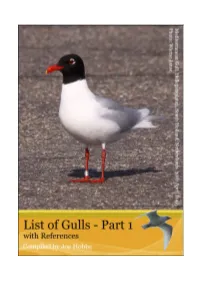

Laridaerefspart1 V1.2.Pdf

Introduction This is the first of two Gull Reference lists. It includes all those species of Gull that are not included in the genus Larus. I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2014 & 2015 to: [email protected]. Grateful thanks to Wietze Janse (http://picasaweb.google.nl/wietze.janse) and Dick Coombes for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2014. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 4.2 accessed April 2014]). Cover Main image: Mediterranean Gull. Hellegatsplaten, South Holland, Netherlands. 30th April 2010. Picture by Wietze Janse. Vignette: Ivory Gull. Baltimore Harbour, Co. Cork, Ireland. 4th March 2009. Picture by Richard H. Coombes. Version Version 1.2 (August 2014). Species Page No. Andean Gull [Chroicocephalus serranus] 19 Audouin's Gull [Ichthyaetus audouinii] 37 Black-billed Gull [Chroicocephalus bulleri] 19 Black-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus ridibundus] 21 Black-legged Kittiwake [Rissa tridactyla] 6 Bonaparte's Gull [Chroicocephalus philadelphia] 16 Brown-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus] 20 Brown-hooded Gull [Chroicocephalus maculipennis] 20 Dolphin Gull [Leucophaeus scoresbii] 31 Franklin's Gull [Leucophaeus pipixcan] 34 Great Black-headed Gull [Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus] 41 Grey Gull [Leucophaeus -

Species Boundaries in the Herring and Lesser Black-Backed Gull Complex J

Species boundaries in the Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex J. Martin Collinson, David T. Parkin, Alan G. Knox, George Sangster and Lars Svensson Caspian Gull David Quinn ABSTRACT The BOURC Taxonomic Sub-committee (TSC) recently published recommendations for the taxonomy of the Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex (Sangster et al. 2007). Six species were recognised: Herring Gull Larus argentatus, Lesser Black-backed Gull L. fuscus, Caspian Gull L. cachinnans,Yellow-legged Gull L. michahellis, Armenian Gull L. armenicus and American Herring Gull L. smithsonianus.This paper reviews the evidence underlying these decisions and highlights some of the areas of uncertainty. 340 © British Birds 101 • July 2008 • 340–363 Herring Gull taxonomy We dedicate this paper to the memory of Andreas Helbig, our former colleague on the BOURC Taxonomic Sub-committee. He was a fine scientist who, in addition to leading the development of the BOU’s taxonomic Guidelines, made significant contributions to our understanding of the evolutionary history of Palearctic birds, especially chiffchaffs and Sylvia warblers. He directed one of the major research programmes into the evolution of the Herring Gull complex. His tragic death, in 2005, leaves a gap in European ornithology that is hard to fill. Introduction taimyrensis is discussed in detail below, and the Until recently, the Herring Gull Larus argentatus name is used in this paper to describe the birds was treated by BOU as a polytypic species, with breeding from the Ob River east to the at least 12 subspecies: argentatus, argenteus, Khatanga (Vaurie 1965). There has been no heuglini, taimyrensis, vegae, smithsonianus, molecular work comparing the similar and atlantis, michahellis, armenicus, cachinnans, intergrading taxa argentatus and argenteus barabensis and mongolicus (Vaurie 1965; BOU directly and any reference to ‘argentatus’ in this 1971; Grant 1986; fig.