Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prey Delivered to Roseate and Common Tern Chicks; Composition and Temporal Variability Carl Safina, Richard H

J. Field Ornithol., 61(3):331-338 PREY DELIVERED TO ROSEATE AND COMMON TERN CHICKS; COMPOSITION AND TEMPORAL VARIABILITY CARL SAFINA, RICHARD H. WAGNER1, DAVID A. WITTING 2, AND KELLYJ. SMITH2 National Audubon Society 306 South Bay Ave Islip, New York 11751 USA Abstract.--We observedprey deliveriesto Roseate(Sterna dougallii) and Common (S. hi- rundo)tern chicks.Roseate Terns were highly specializedand fed their chicksmostly sandeels (Ammodytesamericanus), whereas Common Terns delivered a diversity of prey. Species compositionof deliveredprey varied annually and weekly. Of four major prey species,the proportionof deliveriescontaining anchovies, juvenile bluefish, and herring varied with the time of morning, whereasthe proportionmade up of sandeelsremained generally constant. ENTREGA DE ALIMENTO A POLLUELOS DE STERNA DOUGALLH Y S. HIRUNDO: COMPOSICION Y VARIABILIDAD TEMPORAL Sinopsis.--Obscrvamosla cntregade alimentoa polluelosde Sternadougallii y S. hirundo. Los adultosdc S. dougalliialimcntaron a suspolluclos muy particularmentecon individuos dc Ammodytesamericanus, micntras quc la otra cspccicdc gaviotaalimcnt6 a suspichoncs con una gran divcrsidaddc prcsas.La composici6ndcl alimcntocntrcgado a los pichoncs, result6variable a travis de1cstudio. Dc las cuatrocspccics dc pcccsutilizadas principalmcntc comoalimcnto para lospichoncs, la proporci6ncntrcgada quc contcnlaanchoas, pcz azulado y arcncavari6 a travfisdc lashoras dc la mafiana,micntras quc la quc contcnlaA. americanus pcrmancci6gcncralmcntc constantc. Ever since Volterra (1931) -

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

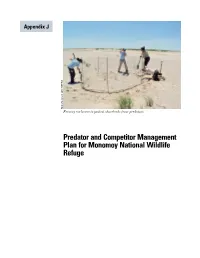

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan Volume 2 Baseline Assessment and Science Framework December 2009 Introduction Volume 2 of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan focuses on the data and scientific aspects of the plan and its implementation. It includes these two separate documents: • Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Planning Area - This Oceans Act-mandated product includes information cataloging the current state of knowledge regarding human uses, natural resources, and other ecosystem factors in Massachusetts ocean waters. • Science Framework - This document provides a blueprint for ocean management- related science and research needs in Massachusetts, including priorities for the next five years. i Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Planning Area Acknowledgements The authors thank Emily Chambliss and Dan Sampson for their help in preparing Geographic Information System (GIS) data for presentation in the figures. We also thank Anne Donovan and Arden Miller, who helped with the editing and layout of this document. Special thanks go to Walter Barnhardt, Ed Bell, Michael Bothner, Erin Burke, Tay Evans, Deb Hadden, Dave Janik, Matt Liebman, Victor Mastone, Adrienne Pappal, Mark Rousseau, Tom Shields, Jan Smith, Page Valentine, John Weber, and Brad Wellock, who helped us write specific sections of this assessment. We are grateful to Wendy Leo, Peter Ralston, and Andrea Rex of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority for data and assistance writing the water quality subchapter. Robert Buchsbaum, Becky Harris, Simon Perkins, and Wayne Petersen from Massachusetts Audubon provided expert advice on the avifauna subchapter. Kevin Brander, David Burns, and Kathleen Keohane from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection and Robin Pearlman from the U.S. -

Dwergstern3.Pdf

99 PRIMARY MOULT, BODY MASS AND MOULT MIGRATION OF LITTLE TERN STERNAALBIFRONS IN NE ITALY GIUSEPPE CHERUBINI, LORENZO SERRA & NICOLA BACCETTI Cherubini G., L. Serra & N. Baccetti 1996. Primary moult, body mass and moult migration of Little Tern Sterna albifrons in NE Italy. Ardea 84: 99 114. Large post-breeding gatherings of Little Terns Sterna albifrons are regu larly observed in the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Here, during five consecutive \ 1/ trapping seasons, 2956 birds were examined and ringed. Their breeding area, as indicated by 163 direct recoveries (mainly juveniles, ringed as chicks), spans over a broad sector of the Adriatic coasts, with colonies lo cated up to 133 km far. During their stay at the study area, adults undergo an almost complete moult. Two partial primary moult cycles can be ob \ served, the first of them being suspended when 2-4 outermost long primar ies have not yet been shed. Pre-migratory body mass build-up, enough for a ~/ flight longer than 1000 km, takes place during the very last days before de parture to the winter quarters, in most cases when the moult has reached a I suspended stage. Active primary moult and body mass increase do overlap in late moulting birds (after 27 August), indicating that the two processes are compatible, in case of time shortage. Post-breeding movements to the Lagoon of Venice seem to fit most requisites of moult migration. Key words: Sterna albifrons - Italy - biometrics - moult migration - ringing - fattening Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca' Fornacetta 9,1-40064 Oz zano Emilia BO, Italy. -

Fastest Migration Highest

GO!” Everyone knows birds can fly. ET’S But not everyone knows that “L certain birds are really, really good at it. Meet a few of these champions of the skies. Flying Acby Ellen eLambeth; art sby Dave Clegg! Highest You don’t have to be a lightweight to fly high. Just look at a Ruppell’s griffon vulture (left). One was recorded flying at an altitude of 36,000 feet. That’s as high as passenger planes fly! In fact, it’s so high that you would pass out from lack of oxygen if you weren’t inside a plane. How does the vulture manage? It has Fastest (on the level) Swifts are birds that have that name for good special blood cells that make a small amount reason: They’re speedy! The swiftest bird using its own of oxygen go a long way. flapping-wing power is the common swift of Europe, Asia, and Africa (below). It’s been clocked at nearly 70 miles per hour. That’s the speed limit for cars on some highways. Vroom-vroom! Fastest (in a dive) Fastest Migration With gravity helping out, a bird can pick up extra speed. Imagine taking a trip of about 4,200 And no bird can go faster than a peregrine falcon in a dive miles. Sure, you could easily do it in an airplane. after prey (right). In fact, no other animal on Earth can go as But a great snipe (right) did it on the wing in just fast as a peregrine: more than 200 miles per hour! three and a half days! That means it averaged about 60 miles The prey, by the way, is usually another bird, per hour during its migration between northern which the peregrine strikes in mid-air with its balled-up Europe and central Africa. -

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: the Importance of Artificial Sites

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: The Importance of Artificial Sites Jeremy J. Hatch Terns are familiar coastal birds in Massachusetts, nesting widely, but they are most numerous from Plymouth southwards. Their numbers have fluctuated over the years, and the history of the four principal species was compiled by Nisbet (1973 and in press). Two of these have nested in Boston Harbor: the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) and the Least Tern (S. albifrons). In the late nineteenth century, the numbers of all terns declined profoundly throughout the Northeast because of intensive shooting of adults for the millinery trade (Doughty 1975), reaching their nadir in the 1890s (Nisbet 1973). Subsequently, numbers rebounded and reached a peak in the 1930s, declined again to the mid-1970s, then increased into the 1990s under vigilant protection (Blodget and Livingston 1996). In contrast, the first terns to nest in Boston Harbor in the twentieth century were not reported until 1968, and there are no records from the 1930s, when the numbers peaked statewide. For much of their subsequent existence the Common Terns have depended upon a sequence of artificial sites. This unusual history is the subject of this article. For successful breeding, terns require both an abimdant food supply and nesting sites safe from predators. Islands in estuaries can be ideal in both respects, and it is likely that terns were numerous in Boston Harbor in early times. There is no direct evidence for — or against — this surmise, but one of the former islands now lying beneath Logan Airport was called Bird Island (Fig. 1) and, like others similarly named, may well have been the site of a tern colony in colonial times. -

Bridled Tern Breeding Record in the United States

SCIENCE areamore closely, and quickly locat- ed a downy Bridled Tern chick crouched under one of the rocks which was usedas a perchby the BRIDLEDTERN adult. We have accumulated addi- tionalrecords of nestingat thissite in subsequentyears. BREEDING BridledTerns breed throughout the Bahamas and the Greater and LesserAntilles, and occur commonly offshoreFlorida and regularlyoff RECORDIN THE other southeasternstates, but this is thefirst evidence of breedingreport- edfor NorthAmerica north of Quin- UNITEDSTATES tana Roo on the Yucatan Peninsula (Howell et al. i99o). In this note we describe the islet, the Roseate Tern colony,and the BridledTern nest byPyne Hoffman, site,and compare the nesting habitat of these terns to that used in the Ba- AlexanderSprunt IV, hamas. The FloridaKeys are flankedto PeterKalla, and Mark Robson the eastand south by a line of coral reefsparalleling the main keysat a distance of 6 to i2 kilometers. The best-developed(and some of the On themorning of July •5, •987, two Terns(Sterna anaethetus) flying low shallowest)reefs occur along the reef of us(Sprunt and Hoffman) visited a overthe colony.One of theseterns margin,adjacent to thedeep water of RoseateTern (Sterna dougallih colony sat for extendedperiods on coral the FloridaStraits. The tern colony on a small coral rubble islet on Peli- rocksin the northeasternpart of the occupiesan isletof approximately canShoal, south of BocaChica Key, isletand circled, calling softly when one-fourthhectare composed of coral MonroeCounty, Florida. During in- we approached.We returnedto the rubble and sand located on a shallow spectionwe observedfour Bridled island that afternoon to examine the sectionof the fringingreef called Bridled Tern on Pelican Shoal. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Environmental Contaminants in Arctic Tern Eggs from Petit Manan Island

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine May 2001 Mission Statement U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service “Our mission is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance the nation’s fish and wildlife and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.” Suggested citation: Mierzykowski S.E., J.L. Megyesi and K.C. Carr. 2001. Environmental contaminants in Arctic tern eggs from Petit Manan Island. USFWS. Spec. Proj. Rep. FY96-MEFO-6-EC. Maine Field Office. Old Town, ME. 40 pp. Report reformatted 1/2009 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine Prepared by: Steven E. Mierzykowski1, Jennifer L. Megyesi2, and Kenneth C. Carr3 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Maine Field Office 1033 South Main Street Old Town, Maine 04468 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Main Street, P.O. Box 279 Milbridge, Maine 04658 3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service New England Field Office 70 Commercial Street, Suite 300 Concord, New Hampshire 03301-5087 May 2001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Petit Manan Island is a 3.5-hectare (~ 9 acre) island that lies approximately 4-kilometers (2.5-miles) from the coastline of Petit Manan Point, Steuben, Washington County, Maine. It is one of nearly 40 coastal islands within the Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge. -

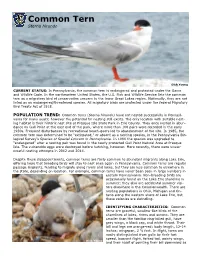

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo

Common Tern Sterna hirundo Dick Young CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the common tern is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. In the northeastern United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the common tern as a migratory bird of conservation concern in the lower Great Lakes region. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Common terns (Sterna hirundo) have not nested successfully in Pennsyl- vania for many years; however the potential for nesting still exists. The only location with suitable nest- ing habitat is their historic nest site at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County. They once nested in abun- dance on Gull Point at the east end of the park, where more than 100 pairs were recorded in the early 1930s. Frequent disturbances by recreational beach-goers led to abandonment of the site. In 1985, the common tern was determined to be “extirpated,” or absent as a nesting species, in the Pennsylvania Bio- logical Survey’s Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. In 1999 the species was upgraded to “endangered” after a nesting pair was found in the newly protected Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle. The vulnerable eggs were destroyed before hatching, however. More recently, there were unsuc- cessful nesting attempts in 2012 and 2014. Despite these disappointments, common terns are fairly common to abundant migrants along Lake Erie, offering hope that breeding birds will stay to nest once again in Pennsylvania. -

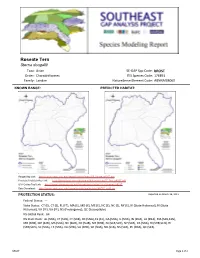

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Brost Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM08060

Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bROST Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM08060 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bROST.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bROST.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bROST Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bROST_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (E), CT (E), FL (FT), MA (E), MD (X), ME (E), NC (E), NC (E), NY (E), RI (State Historical), RI (State Historical), VA (LE), VA (LE), NS (Endangered), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G4 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), CT (S1B), CT (S1B), DE (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), IL (SNA), IN (SNA), LA (SNA), MA (S2B,S3N), MD (SHB), ME (S2B), MS (SNA), NC (SUB), NC (SUB), NH (SHB), NJ (S1B,S1N), NY (S1B), PA (SNA), RI (SHB,S1N), RI (SHB,S1N), SC (SNA), TX (SNA), VA (SHB), VA (SHB), WI (SNA), NB (S1B), NS (S1B), PE (SNA), QC (S1B) bROST Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 US Dept.