Dwergstern3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula Antillarum Lesson Other

Common Name: LEAST TERN Scientific Name: Sternula antillarum Lesson Other Commonly Used Names: Little tern, silver turnlet, sea swallow, minute tern, little striker, and killing peter Previously Used Names: Sterna antillarum Family: Laridae Rarity Ranks: G4/S3 State Legal Status: Rare Federal Legal Status: Interior population listed as endangered. Other populations are not federally listed. Federal Wetland Status: N/A Description: Georgia's smallest tern at about 23 cm (9 in) in length with a 50 cm (20 in) wingspread, the least tern is white with pale gray feathers on the back and upper surfaces of the wings, except for a narrow black stripe along the leading edge of the upper wing feathers. The least tern has a black cap with a small patch of white on the forehead. In summer, the adult has a yellow bill with a black tip and yellow to orange feet and legs. Its tail is deeply forked. In winter, the bill, legs and feet are black. The juvenile has a black bill and yellow legs, and the feathers of the back have dark margins, giving the bird a distinctly "scaled" appearance. The least tern's small size, white forehead, and yellow bill serve to distinguish it from other terns. Similar Species: The adult sandwich tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis) is the most similar species to the adult least tern, but is much larger at about 38 cm (15 in) in length and has a black bill with a pale (usually yellow) tip and black legs. Juvenile least terns and sandwich terns look very similar in appearance. -

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

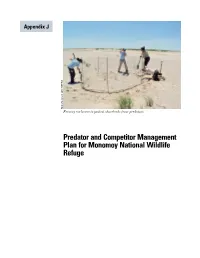

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Updating the Seabird Fauna of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia

Tirtaningtyas & Yordan: Seabirds of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia, update 11 UPDATING THE SEABIRD FAUNA OF JAKARTA BAY, INDONESIA FRANSISCA N. TIRTANINGTYAS¹ & KHALEB YORDAN² ¹ Burung Laut Indonesia, Depok, East Java 16421, Indonesia ([email protected]) ² Jakarta Birder, Jl. Betung 1/161, Pondok Bambu, East Jakarta 13430, Indonesia Received 17 August 2016, accepted 20 October 2016 ABSTRACT TIRTANINGTYAS, F.N. & YORDAN, K. 2017. Updating the seabird fauna of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia. Marine Ornithology 45: 11–16. Jakarta Bay, with an area of about 490 km2, is located at the edge of the Sunda Straits between Java and Sumatra, positioned on the Java coast between the capes of Tanjung Pasir in the west and Tanjung Karawang in the east. Its marine avifauna has been little studied. The ecology of the area is under threat owing to 1) Jakarta’s Governor Regulation No. 121/2012 zoning the northern coastal area of Jakarta for development through the creation of new islands or reclamation; 2) the condition of Jakarta’s rivers, which are becoming more heavily polluted from increasing domestic and industrial waste flowing into the bay; and 3) other factors such as incidental take. Because of these factors, it is useful to update knowledge of the seabird fauna of Jakarta Bay, part of the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. In 2011–2014 we conducted surveys to quantify seabird occurrence in the area. We identified 18 seabird species, 13 of which were new records for Jakarta Bay; more detailed information is presented for Christmas Island Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi. To better protect Jakarta Bay and its wildlife, regular monitoring is strongly recommended, and such monitoring is best conducted in cooperation with the staff of local government, local people, local non-governmental organization personnel and birdwatchers. -

LEAST TERN Sternula Antillarum Non-Breeding Visitor, Occasional; Rare Breeding Visitor Monotypic

LEAST TERN Sternula antillarum non-breeding visitor, occasional; rare breeding visitor monotypic The Least Tern breeds across the s. United States S through Mexico and the Caribbean, and it winters in C-S America (AOU 1998). This species and the closely related Little Tern are difficult to distinguish, which has led to uncertainty about the status of each species in the Hawaiian Islands (Clapp 1989; see Little Tern). Least Tern appears to be more common than Little Tern, with substantiated records from Midway to Hawaii I, confirmed breeding attempts at both of these locations, and evidence for successful reproductive efforts as well on O'ahu and possibly French Frigate Shoals. As with Little Tern, the majority of records involve adults and one-year old birds in May- Aug, and several records of juvenile and first-fall birds in Aug-Oct reflect the likelihood of local reproduction. Least and Little terns were split at the genus level from Sterna by the AOU (2006). In the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, well-documented Least Terns have been recorded from Kure 6-8 Aug 2016 (HRBP 6662-6663); Midway 5-10 May 1989, 13-14 Sep 1990 (2 individuals), 5-22 Jul 1993 (pair), 15 Jun-Sep 1999 (3 adults involved in an unsuccessful breeding attempt; Pyle et al. 2001, NAB 53:436; HRBP 1234-1236, 1289- 1292 published NAB 55:5-6), 8 (along with 2 Little Terns) 8-10 Sep 2002 (Rowlett 2002), 2 on 22 Jun 2015 (HRBP 6658), and at least 2 (among 12 Sternula terns) 22 Oct 2016 (HRBP 6664). -

(Sternula Albifrons) in Ria Formosa, Algarve

Breeding Success and Feeding Ecology of Little Tern (Sternula albifrons) in Ria Formosa, Algarve. Dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Coimbra para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Biologia, realizada sob a orientação científica do Professor Doutor Jaime Albino Ramos (Universidade de Coimbra) e do Doutor Vítor Hugo Paiva (Universidade de Coimbra). Ana Carolina Lopes Correia Departamento de Ciências da Vida Universidade de Coimbra 2016 Agradecimentos Não poderia deixar de agradecer a quem de alguma forma contribuiu para a realização deste trabalho. Fui sempre acompanhada por pessoas dedicadas, presentes, interessadas e que me motivaram e me ajudaram a realizar este projeto da melhor forma possível. A todas estas pessoas o meu sincero Muito Obrigada! Em primeiro lugar quero agradecer aos meus orientadores Professor Doutor Jaime Albino Ramos e Doutor Vítor Hugo Paiva por toda a ajuda, dedicação, apoio, paciência, comentários e revisões. Muito obrigada pela oportunidade de trabalhar num tema tão interessante sempre rodeada de excelentes profissionais que são também pessoas fantásticas. À Ana Quaresma por ter sido incansável durante o trabalho de campo, por toda a ajuda, apoio e partilha de conhecimento. Ao Mestre Alves pela hospitalidade e ensinamentos, ao Sr. Silvério, ao Sr. Capela, ao Filipe Ceia e ao Lucas pela ajuda no trabalho de campo. À ANIMARIS pelo transporte para a ilha Deserta. À Catarina Lopes e à Patrícia Pedro pela ajuda na identificação de otólitos. To Naomi for helping me identifying the scales and for all the support and friendship. À Diana (Di), por partilhar comigo todas as etapas referentes à tese, pelo companheirismo, por todo o apoio e pela capacidade de melhorar o meu dia com a sua alegria contagiante. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo

Common Tern Sterna hirundo Dick Young CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the common tern is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. In the northeastern United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the common tern as a migratory bird of conservation concern in the lower Great Lakes region. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Common terns (Sterna hirundo) have not nested successfully in Pennsyl- vania for many years; however the potential for nesting still exists. The only location with suitable nest- ing habitat is their historic nest site at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County. They once nested in abun- dance on Gull Point at the east end of the park, where more than 100 pairs were recorded in the early 1930s. Frequent disturbances by recreational beach-goers led to abandonment of the site. In 1985, the common tern was determined to be “extirpated,” or absent as a nesting species, in the Pennsylvania Bio- logical Survey’s Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. In 1999 the species was upgraded to “endangered” after a nesting pair was found in the newly protected Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle. The vulnerable eggs were destroyed before hatching, however. More recently, there were unsuc- cessful nesting attempts in 2012 and 2014. Despite these disappointments, common terns are fairly common to abundant migrants along Lake Erie, offering hope that breeding birds will stay to nest once again in Pennsylvania. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

The Birds of Lido Beach

The Birds of Lido Beach An introduction to the birds which nest on and visit the beaches between Long Beach and Jones Inlet, with a special emphasis on the NYS endangered Piping Plover Paul Friedman Ver. 1.1 Best if viewed in full screen mode 1 Featured Birds Nest on the Beach Migrants* • Piping Plovers • Sanderlings • American Oystercatchers • Dunlins • Common Terns • Semipalmated Plovers • Least Terns • Black Skimmers * These three are just a few of the many migrants which use our beach as a layover 2 The Migrants Nest in the far north (Greenland , sub-arctic, etc.) – seen in Spring and mid/late Summer as they migrate to and from their nesting grounds Probe for food in the wet sand along the ocean’s edge • Sanderlings - most numerous of the three - can be seen in large groups in flight and running back and forth probing the wet sand left by a receding wave • Dunlins – characterized by long drooping bill – can be found with Sanderlings • Semipalmated Plovers– similar to Piping Plover in size and shape; and have distinctive black bands on the neck and forehead. Sanderlings Dunlins Semipalmated Plovers 3 Sanderlings Acrobatic, precision fliers; seen in large flocks. The entire flock can Note black legs and straight black bill turn on a dime; a required skill when evading a falcon. Large groups chase receding waves to…… … probe the wet sand for food 4 Dunlins Note droop in bill. Black belly is breeding plumage. Probing the wet sand for food Often found mixed in with Sanderlings At ocean’s edge 5 Semipalmated Plovers Note black forehead and black neck band Pictured here with its close cousin, the Piping Plover 6 Slurping a marine worm as one might a strand of spaghetti Taking flight The Lido Beach Nesting Birds o All nest in scrapes in sand between high tide and dunes o Two strategies – nest in colonies or nest in solitary pairs • Colonial Nesting Birds 1. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose